RESEARCH ARTICLE

Recovery-oriented Programmes to Support the Recovery Approach to Mental Health in Africa: Findings of PhD: A Scoping Review

Kealeboga Kebope Mongie1, *, Manyedi Eva2, Phiri-Moloko Salaminah2

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2023Volume: 17

E-location ID: e187443462302140

Publisher ID: e187443462302140

DOI: 10.2174/18744346-v17-230223-2022-152

Article History:

Received Date: 11/10/2022Revision Received Date: 13/1/2023

Acceptance Date: 16/1/2023

Electronic publication date: 27/03/2023

Collection year: 2023

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background:

Researchers in the field of mental health and people living with a diagnosis of mental illness advocate recovery-oriented mental healthcare approach. Most developed countries have adopted the recovery-oriented approach in mental health facilities to care for people diagnosed with mental illness. However, Africa is left behind in implementing and adopting such a model of care.

Objective:

The objective of the review was to explore the global literature on recovery-oriented mental healthcare programmes, where they originate, are implemented, as well as identify gaps in the literature for further research.

Methods:

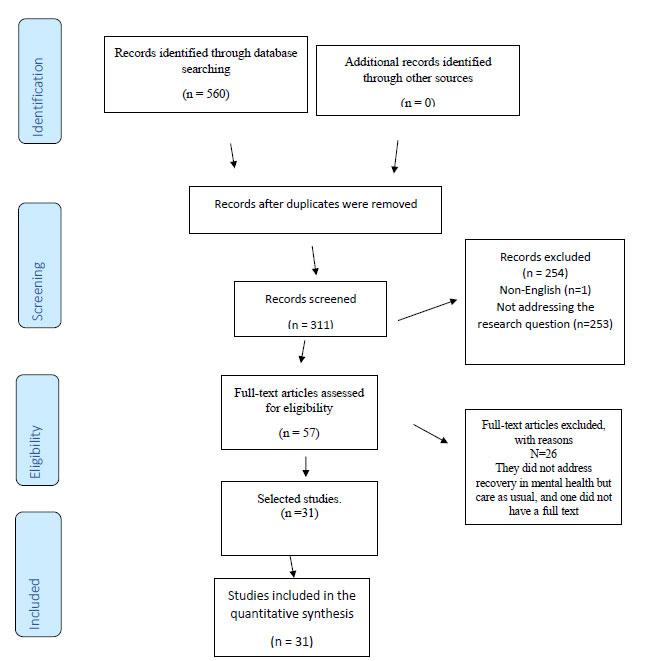

The scoping review utilised a refined framework of Arskey and O'Mally (2005) by Levac et al. (Levac, Colquhoun, & O'Brien, 2010). Different databases were systematically searched, and The PRISMA Flow Chart was used to select the articles included in the review.

Results:

From the initial 560 identified papers, 31 met the review’s inclusion criteria. The results indicated that most recovery-oriented programmes were developed in well-developed Western countries. It was evident from the included studies that the recovery-oriented mental healthcare programmes were effective for and appreciated by people diagnosed with mental illness. None of the identified and included studies discussed any developed recovery-oriented mental healthcare programme in Africa.

Implications for Nursing:

Nurses need to understand and implement the latest treatment modalities in mental health practice, and recovery-oriented care is one such practice.

Conclusion:

The review established that most recovery mental healthcare programmes are from Western high-resourced countries and have proven to be effective and appreciated by people diagnosed with mental illness. At the time of the review, no study indicated that a recovery-oriented mental healthcare programme was developed in the Sub-Saharan African context. Therefore, this calls for Africa to develop and implement a recovery-oriented programme to meet the mental health needs of people diagnosed with mental illness.

1. INTRODUCTION

The recovery-oriented approach to care in mental health is now under implementation in various western high-income countries [1, 2]. The approach came to light following evidence that people presenting with severe mental illness can recover and live productive lives [3]. However, the definition of recovery remains challenging as it is described from multiple individuals' and researchers' perspectives. There seems to be some individuality or, more to say, personal experience attached to some definitions of recovery from mental illness [4, 5]. A common observation in the definitions of recovery is that it is a unique personal journey which is more than symptom remission [6]. The most commonly acceptable definition of recovery is by Anthony [7], who defines it as “A deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, feelings, goals, skills, and/or roles. It is a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with the limitations caused by illness. Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of mental illness”. Nevertheless, there is still no agreement on the definition of recovery, hence the call from researchers for a standard definition acceptable to all [5, 8,]. The review conceptualised recovery as being able to live positively with a diagnosis of mental illness, performing the activities of daily living and participating in family, work, and community activities without being hindered by the effects of mental illness. It entails being happy and enjoying life without being trapped by the effects of having a mental illness. According to the Victorian Department of Health 2011, as cited in a study [9], recovery-oriented mental healthcare provides client-centred care in an environment that fosters optimism and hope, which is facilitated by a caring and respectful staff.

Most western countries are implementing a recovery-oriented mental healthcare approach to caring for people with a diagnosis of mental illness [5, 10, 11]. However, due to the lack of a standardised definition of what recovery should entail, the implementation remains a challenge [2, 5]. Therefore, researchers have designed programmes, frameworks, guidelines, and visions for their mental health settings to address implementation challenges [2]. However, the contexts and subjects of the studies that have led to the development of such programmes and frameworks have been questioned as it seems they were all developed in high-income countries [11, 12].

Research points to a monoculture of recovery as more programmes are conceptualised from the personal descriptions of individuals and consumer movements from recovered clients from high-income communities [11, 12]. Furthermore, recovery can be considered as a “thing” of western societies and more advanced mental health approaches Lavallee & Poole [12]. Therefore, we need to acknowledge indigenous people and tailor culture-specific recovery programs for recovery programs or frameworks to be effective. Recovery-oriented approach to the care of people with mental illness is practised in the United States of America, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. All these countries are classified as high-income countries [13]. A special report in 2014 by multi-national pro-recovery researchers from various countries called for more culturally tailored recovery programmes which are more resource and service contextual [11].

Most African countries are still without mental health policies, and recovery principles are not implemented despite deinstitutionalisation in some countries [14]. Additionally, recovery-oriented mental health services are still not yet known [15]. Sub-Saharan Africa remains one of the poorest areas of the globe and has a wide gap in mental health resources for its people [14]. The lack of policies alone may imply that mental health issues and management continue to remain less prioritised in Africa. Consequently, that hampers the implementation of the latest treatment modalities approaches in mental health, such as recovery-oriented mental healthcare [16]. Botswana is a country in sub-Saharan Africa categorised as a middle-income country [17]. Currently, the care of people diagnosed with mental illness in Botswana is under the influence of the biomedical approach through psychotropic drugs. Nurses are the primary mental healthcare providers in Botswana due to the shortage of psychiatrists, an observation common in most African countries and the world in general [18]. There are approximately 0.29 psychiatrists per 100 000 people in Botswana which makes it difficult for psychiatrists to see all patients on arrival [19]. Therefore, most patients on arrival at mental health facilities are first attended to by psychiatric mental health nurses or general nurses. Psychiatric mental health nurses are the pillar of mental health services in Botswana. Currently, to the best of the researcher's knowledge, no policy, guideline, or programme addresses recovery-oriented mental healthcare principles. Botswana operates with one referral mental hospital south of Botswana and four psychiatric units attached to four general hospitals [19].

2. METHODS

The scoping review aimed at exploring the global literature on recovery-oriented mental healthcare programmes. It focused on defining recovery-oriented mental healthcare programmes and how they have been implemented globally, identifying gaps in the literature for further research. The review focused on how the studies were conducted, paying attention to the population and the findings. The scoping review served as a framework of accessing the types of evidence available on the subject and identifying knowledge gaps [20]. The review utilised the refined framework of Arksey, & O’Malley [21], which was refined by Levac et al. [22]. The following steps of the framework were used to structure the scoping review: identification of the research question and the relevant studies or objectives, inclusion and exclusion criteria, search for evidence, selection of evidence (relevant studies), extraction of evidence, chart of the data, collation, summary, and report of the results.

2.1. Identification of the Research Question/or Objectives

The main aim of this scoping review was to explore existing literature on recovery-oriented mental health programmes, their implementation, challenges, effectiveness, and identify gaps in the literature for further research. The review addressed the following specific objectives:

- Describe recovery-oriented mental health approaches.

- Describe how recovery-oriented mental healthcare programmes have been implemented.

- Identify challenges in the implementation of recovery-oriented mental health programmes.

- Describe the effectiveness of recovery-oriented mental health programmes.

- Describe the adoption and implementation of recovery-oriented mental health approaches in sub-Saharan Africa and in particular, Botswana.

The review answers the following questions:

- What literature is available on mental health-related recovery-oriented programmes?

- How are the recovery-oriented mental healthcare programmes being implemented?

- What are the challenges of implementing recovery-oriented mental healthcare programmes?

- How effective are the recovery-oriented mental healthcare programmes?

- How have the recovery-oriented mental healthcare programmes been adopted and implemented in Sub-Sahara Africa?

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The studies were selected based on the formulated inclusion and exclusion criteria. All peer-reviewed studies from January 2010 to April 2022, published in English, were included in the study. The selected studies were on the implementation of mental health/illness recovery programmes, evaluation of recovery programmes, the effectiveness of recovery programmes and validation of the recovery programmes. Studies that focused only on substance use and selected narcotics use and rehabilitation only without a diagnosis of mental illness were excluded as the study intended to find the effectiveness of already existing programmes on recovery from mental illness. The study protocols were also excluded as they did not serve the purpose of the review.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

- All peer-reviewed papers published in 2010 that broadly addressed the study's objectives.

- Reports, summits or conference reports with well-elaborated recovery-oriented mental health frameworks/guidelines or visions.

- All the studies and reports written in English were included.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

- All peer-reviewed studies published before 2010 on recovery programmes and frameworks/guidelines.

- All studies with mental health programmes that do not address recovery-oriented mental healthcare app-roaches.

- All studies not published in English.

2.5. Search Strategy

The following electronic databases were searched to answer the research question: Sabinet, Medline, PubMed Academic Search, Cinahl, PsychARTICLES, and Psych Info. In addition, reference lists of the included articles in the significant articles were also searched. Keywords of relevant studies and the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms such as “mental health recovery, mental illness, mental health, and mental health intervention programme” were used. This review's string/Boolean search terms included mental health AND recovery approach AND recovery programmes. The review included all study designs to select articles. Copies of all articles that meet or appear to meet the inclusion criteria were obtained. Then two reviewers, the researcher, and the research assistant, independently scrutinised the retrieved studies from databases to determine their eligibility for inclusion in the study.

2.6. Search Strategy for PubMed

The search was conducted between 2010 to April 2022, and the string/Boolean search terms mental health AND recovery approach AND recovery programmes were used. The initial search produced 296 articles. The articles were loaded on the Endnote X9 software reference and only 82 articles remained after duplicates were removed. The remaining articles were then combined with other articles to make one data set of studies.

2.7. Study Selection

The first stage involved the independent title selection of articles from the proposed databases by the two reviewers to determine their eligibility. The identified articles were uploaded on the Endnote X9 software reference, and duplicates were removed. The two reviewers then independently screened the identified abstracts and full-text studies to determine whether to include them. The University Librarian was contacted for assistance in locating articles and contacting the authors through emails for studies without full texts. Any discrepancy that arose between the reviewers was addressed. (Fig. 1: PRISMA Flow Chart).

2.8. Data Extraction

A data charting form was developed from all the studies included, based on the inclusion criteria. The researcher and assistant independently extracted information that included the author, intervention, setting, design, aim, significant findings and other relevant information, such as the origin and challenges of implementing the recovery-oriented approach. All the reasons for excluding studies are reported.

2.9. Quality Appraisal

A Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version of 2018 was used to appraise the quality of the included studies independently by the two reviewers [23]. Any discrepancies were solved, and a consensus was reached. MMAT assessed the eligibility of the included studies by looking at the study’s aim, target participants, study design, data collection and analysis, ethical issues and study presentations. All the studies were rated on a scale of 50 to 100. Those who scored 50 to 65 were viewed as good quality, and those who scored more than 66-100 were considered to be very good. Table 1 shows the summary of the included studies.

|

Fig. 1. PRISMA Flow Chart 2009 showing illustration screening process of studies. |

| References | Intervention | Setting | Design | Population | Aim | Major Findings | Any Important Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [26] | Meaning of recovery and Applicability of Wellness Recovery Action Plan WRAP (workshops) | Japanese Canadians living in Canadian metropolitan city | Qualitative explorative | First-generation older Japanese-speaking Canadians with mental illness N=8 |

To explore whether the Well-ness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP), a recovery-based programme, is applicable to Japanese-Canadian older adults | -WRAP helpful - Recovery helpful in finding self-worth. -Be positive and hopeful -Advocate for their rights |

Origin USA Conducted Canada |

| [41] | Recovery Guide for you-RG in inpatient care | Inpatients wards in Sweden | Mixed method | Staff member working in 14 Sweden inpatient units | To investigate the implementation of RG intervention in Inpatient Mental Health Services (MHS) settings in order to improve the quality of care | -All perceived RG to be legitimate, right and acceptable - Potential to provide staff with vital information on recovery -Staff can integrate information into clients’ plan of care |

Origin: Sweden Conducted: Sweden Challenges Lack of resources, anticipated increased workload, lack of motivation (all resolved) |

| [48] | GetReal | Selected mental health Units in England | Qualitative Case study analysis | Existing data from 19 units that took part in the RCT in the Rehabilitation Effectiveness |

To explore factors associated with variation between sustaining recovery-oriented practice during the GetReal intervention | Positive signs to sustain long-term Recovery-Oriented practice (ROP) | Origin: UK Conducted: UK Challenges -Have a change agent or champion -Managerial support -Organisational structures |

| [47] | Training in Comprehensive Approach to Rehabilitation (CARe) Methodology for people with mental illness | National supported housing alliance in the Netherlands | Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial | Three Organizations for sheltered and supported housing in the Netherlands 893 clients |

To investigate the effectiveness of CARe by means of the training staff of methodology on personal recovery of clients with mental illness | -No difference in both groups -Quality of life improved in both groups |

Origin: Netherlands Conducted: Netherlands Challenges Small sample size |

| [52] | Person Centered Care Planning (PCCP) | Permanent supportive housing sites from a recovery-oriented, community |

Qualitative explorative study | Staff and tenants of 4 permanent supportive housing from recovery oriented community based organizations | Understand multiple stakeholder perspectives implementing a recovery- oriented approach to service planning in supportive housing programs serving people with lived experience of mental illnesses |

-Service plan served as an institutional reminder to staff and service users -Users and implementers viewed the service as rigid -Plan is seen as obligatory and does not cater to the individual needs of users |

Origin: USA Conducted: USA Challenges: Rigid requirements undermine the provision of recovery-oriented care |

| [31] | Self-Direction program For people living with mental illness | One State in USA offering Self-Directed Program | Qualitative explorative –Content analysis | Former and present participants of Self-Directed Program | Explore the participants ‘experiences of Self-Direction Program | -Positive relation between Self-direction and recovery - recovery seen as dynamic and interrelated |

Origin: USA Conducted: USA |

| [42] | Illness Management and Recovery (IMR | Danish Community services | Randomized assessor-blinded multi-center clinical trial | People with schizophrenia and bipolar diagnoses participated | The aim of this randomized trial was to investigate the effects of the IMR program compared with treatment as usual in Danish patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder | -No significance was found on the functioning, symptoms, substance abuse or service utilization in those who were in the program compared to the control group | Origin: USA Conducted: Denmark |

| [54] | Art Therapy Project | Australian Secure extended care Unit Australia | Qualitative descriptive design | Consumers in rural Australia of an art therapy project and nurse managers and therapists in recovery-oriented rehabilitation programs | 1. Explore the experiences of consumers who participated in the project 2. Examine the views of nurse managers and art therapists on recovery oriented rehabilitation programs in the context of Making Precious Things |

-Consumers found the experience helpful -Service managers and art therapists supported the program, but there were systematic barriers to implementation |

Origin: Australia Conducted: Australia Challenges Biomedical model Loss of clinical experts Lack of understanding of recovery-oriented care |

| [40] | Critical time intervention-task shifting (CTI-TS) |

Brazil and Chile | Secondary Qualitative data analysis | Existing Data collected as part of a larger study that evaluated the pilot CTI-TS study in Brazil & Chile |

Analyses of users’ perspectives and experiences regarding the implementation of these adaptations in Brazil and Chile |

-Results show adoption is promising -Users expressed promising use of community mental health intervention |

Origin: UK Conducted: Brazil/Chile Challenges Stigma towards peers Mental health stigma |

| [39] | Patient engagement | A mental healthcare organization in Montreal (Quebec, Canada) | Qualitative single case study | Service users Committee Managers Executive managers Researchers Project managers Administrators |

Shed light on patient engagement in mental health, more specific, the implementation of a structure for patient engagement on a strategic organizational level |

-Led to improved patient partner participation -Reduced stigma within the organisational committee |

Origin: USA Conducted: Canada Challenges Resistance towards patient participation and the existence of stigma |

| [28] | Intervention nThe Steps to Recovery (STR) |

Mental health Facilities within Tess Esk and Wear Valleys NHS Foundation (TEWV) caring for older people with mental illnesses | Prospective cohort repeated-measure | Older people with mental illnesses with TEWV mental health facilities | Evaluation of group based intervention for older individuals receiving mental health services | -100% evaluated the STR group as having a positive effect on their recovery -reported improved mental wellbeing and recovery |

Origin: UK Conducted: UK Challenges Structured programmes |

| [44] | Prevention and Recovery Care (PARC) | Victoria, Australia | A purpose-designed survey (mixed methods) | Managers of the 19 selected TARC facilities in Victoria N=19 |

Describe the 19 PARC services operating in Victoria | -Emerging evidence that PARCs are providing recovery-oriented services that offer consumers autonomy and social inclusion, which future studies may find links to a positive consumer experience |

Origin: Australia Conducted: Australia Challenges Variation in funding, content, and quality of care |

| [53] | Intermediate Stay Mental Health Unit (ISMHU) 6 weeks intervention, implemented within an Integrated Recovery-Oriented Model (IRM) |

Newcastle, Australia (ISMHU) | Mixed methods | Admitted clients at an Intermediate Stay Mental Health Unit (ISMHU) and train |

Evaluation of the program and on the establishment of ISMHU and implementation of IRM. Characterise the admitted patients and quantify recovery needs and priorities on admission and any changes during admission | -Clients improved in symptoms and functioning from admission to discharge -Clients valued model of care, holistic approach, educational sessions, family and carer involvement and the environment |

Origin: Australia Conducted: Australia |

| [5] | The intervention comprised four full-day workshops and an in-team half-day session on supporting recovery |

Mental health services & community- based and in-patient rehabilitation adult mental health teams for the inner-city London |

A quasi-experimental design | Staff of 22 multidisciplinary community and rehabilitation teams providing mental health services |

Evaluation of the implementation of recovery-orientated practice through training across a system of mental health services |

Changes in staff approach to care included a holistic care approach to care -Shift from focusing on maintenance to improved mental health and outcomes -Utilization of recovery-related terminology |

Origin: UK Conducted: UK Challenges Resources More staff and funding skilled experts in recovery |

| [45] | Evaluation of PARC by service users, carers, and staff | Residential Mental Health Recovery Service in North Queensland, Australia | Participatory research | Staff, service users, and carers of residential mental health service | Evaluation of a residential Mental health Service using a newly developed framework | staff supported and valued -PAR is recovery focused -Consumers felt supported to come up with their own recovery plans |

Origin: Australia Conducted: Australia |

| [51] | Wellness Recovery Action Planning (WRAP) educational programme | Multiple sites in Ireland | Mixed method approach Pre and post |

People with personal experience of mental health problems, practitioners in mental health facilities and carers and family members of people with mental problems who participated in the WRAP programme | To evaluate the effects of WRAP | All had a high degree of knowledge pre and post -Attitudes towards recovery was good pre even positive post -Participants agreed with WRAP beliefs on recovery. Beliefs on WRAP increased more after intervention -Confidence in applying WRAP skills increased -All felt that they can teach others WRAP beliefs |

Origin: USA Conducted: Ireland |

| [36] | ‘therapeutic horticulture’ (TH) within Mental Health Recovery Programme |

Mental Health Recovery Program (MHRP) using TH to support people with mental health problems in the recovery process | Mixed methods: four semi-structured focus group interviews |

People with a diagnosis of mental health problems in a community-based setting | Evaluate the impact of a mental health recovery programme that used therapeutic horticulture as an intervention to reduce social inclusion and improve engagement for people with mental health problems | Improvement in mental health social networks and relationships -Development of new skills; others were employed as confidence -Self-esteem and skills improved -Improvement in mental health wellbeing |

Origin: UK Conducted: UK |

| [56] | Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) program Standard Case-Management Program and served as a control group |

Suwon Mental Health Center Korea |

Pre and post comparative evaluation study | Individuals with a diagnosis of mental illness at the Suwon Mental Health Center | To evaluate the effect of an Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) program on psychiatric symptoms, global functioning, life satisfaction, and recovery-promoting relationships among Individuals with mental illness. |

-ACT reduction in severity of symptoms but not significantly greater than the control group -ACT showed a significant increase in GAF –No difference in life satisfaction |

Origin: USA Conducted: Korea |

| [32] | ‘Housing First’ approach Vs Treatment as Usual group |

Existing data from in-depth qualitative interviews of participants from the Toronto, Ontario site of the ‘At Home/Chez Soi’ Project |

Data analysis of existing qualitative data using constant comparative methods (RCT) | Existing data from participants from the Toronto, Ontario site of the ‘At Home/Chez Soi’ Project.(At Home/Chez Soi’ study |

Explores perspectives on hopes for recovery and the role of housing in these hopes from the perspective of homeless adults experiencing mental illness |

-Many associated recovery with starting over -Housed was key to recovery, the first step to rebuilding their lives *improvement in health and well-being, physical health and sleep improved *improved emotional being & maintaining relationships |

Origin: USA Conducted: Canada |

| [34] | Consumer-run mental health services | Open Arms (a pseudonym) is a Consumer-run mental health centre |

Modified ethnographic study and semi-structured interviews | Open Arms members—with multiple admissions with bipolar and psychosis. Both staff and users | To learn what is distinctive about consumer-run services-e.g., how they might strengthen personal capacity for social integration and explore how the development of these capacities might promote recovery |

-Support of one another is important -Members are accountable for one another -Members well connected. Relationships are authentic. -Center helps members in their recovery |

Origin: USA Conducted: USA |

| [43] | Auto videography | Mental Health Asso- ciation of South-eastern Pennsylvania (MHASP) |

Randomised trial based on the participatory research model | People with serious mental illness who completed a recovery-oriented programme at (MHASP) | Assess whether Autivideography was a feasible method to use with mental health consumers and its benefits | -Intervention facilitated recovery through self-reflection -Reciprocity and advocacy of others with MI -Videos viewed as powerful tools for education |

Origin: USA Conducted: USA |

| [46] | Social Point” program-Social inclusion activities |

Mental healthcare services in Moderna- Social Point USA |

A cross-sectional design-comparative study | People with non-affective psychosis who participated in social inclusion programme | Whether social interventions offered by Social Point have better outcomes for areas of personal and social recovery, especially areas of self-esteem, self-stigma, and perceived quality of life | -Intervention group showed lesser impairment in areas of physical and social functioning -Internalised stigma and quality of life were better in the waiting list group |

Origin: USA Conducted: USA Challenges Internalized stigma experienced by the intervention group |

| [49] | Illness Management and recovery (IMR) for people with serious MI integrated in Assertive Community Treatment (ACT | Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) in two States USA | A small-scale cluster randomized controlled design | Eight ACT teams and four from each state with no prior training in IMR (101 people with serious mental illness | Feasibility of implementing IMR within ACT and its effectiveness | Promising evidence to implement IMR within ACT | Origin: USA Conducted: USA |

| [50] | Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) for people with serious MI integrated in Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) | 11 ACT that implemented ACT | Qualitative study Semi structured interviews |

- service users -Staff in 11 ACT teams |

Assess feasibility, advantages/disadvantages, and factors that hinder or facilitate the implementation of IMR with the ACT team | Service users and staff benefitted - Staff and users felt IMR in ACT improved the recovery focus of users -Users expressed good personal outcomes in terms of managing symptoms and understanding their condition -Staff improved clinical skills -Facilitated building of relationships among staff and users -Peer support |

Origin: USA Conducted: USA Challenges included clients' symptoms, and competing normal day duties for staff vs IMR teaching |

| [29] | Medication-free treatment programme in Bergen, Western Norway | Mental health services | Qualitative descriptive study | People with psychosis registered as patients in one of two district psychiatric centers |

Investigate the experiences of recovery following new treatment options and choices | Offered clients to have treatment options -Improved interpersonal relations between users and staff -Communication improved |

Origin: Norway Conducted: Norway Challenges lack of rights in treatment choice for clients - sharing of information by therapists poor |

| [37] | Recovery Camp | Adventure camp in Australia | Descriptive phenomenological approach | People with mental illness who attend a Recovery camp Program. | How the program has contributed to the recovery of the participants | Participants felt empowered to -Live fulfilling life -Confidence to socialise -Improved relationship with self and others -Improved participation |

Origin: Australia Conducted: Australia |

| [35] | Opening Doors to Recovery. (ODR) |

Southeast Georgia | Longitudinal study –Semi Structured interview of number participants 6 months after implementation |

New community-based, recovery- oriented “community navigation” program (Consumers, Navigators, mental professionals, and all involved in designing and implementing the programme) |

Conduct an initial program evaluation of ODR and its community navigation services | Hopes and strength, Good collaboration among stakeholders noted in running the programme -Garnered support for implementation -Relationships facilitated implementation -Consumers felt supported - Leadership fully supported the programme |

Origin: USA Conducted: USA Challenges Slow implementation, insufficient housing, lack of fidelity across teams, peers feel devalued |

| [55] | Assertive Community treatment (ACT) |

Participants included staff and consumers on two ACT teams ( selected from certified ACT teams in Indiana. |

Mixed methods comparative methods | 2 ACT teams 2 rated low and 2 high in the provision of recovery oriented services Staff and consumers of mental health services. | Identify, within one state, extremes of recovery orientation and use multiple methods to examine how teams differed |

The high-recovery-oriented team had greater consumer involvement in treatment planning, which showed evidenced language supportive of the consumer. Strengths self-directed goals - High-recovery-oriented team had consumers on medication monitoring -More family involvement in the care of clients |

Origin: USA Conducted: USA |

| [33] | Treatment in Supportive Housing |

Supportive housing organization that participated in a larger National Institute of Mental Health- |

Longitudinal qualitative design -In-depth interviews |

Staff (case managers) of supportive-housing organization that participated in a larger National Institute of Mental Health- |

To examine how frontline providers enact their case management roles with consumers living in supportive housing | - Treatment centers on adherence to medication & insight and viewed as key to recovery. Those without insight into their illness were viewed as challenging. Consumers should take treatment for life. noncompliance viewed as not housing ready |

Origin: USA Conducted: USA |

| [30] | Housing First (HF) program- with ACT | Housing first for people with SMI and homeless Lille, Marseille, Paris and Toulouse France | Randomised controlled trial | Homeless people with SMI in selected sites from Lille, Marseille, Paris and Toulouse France | The effectiveness of housing first in reducing the hospital and emergency use | -Intervention showed reduced hospital stay, -housing stability, and quality of life but not on other health related outcomes like substance abuse and dependency |

Origin: USA Conducted France |

| [38] | Partners in Recovery (PIR) Australia |

Nepean Blue Mountains Consortium | Program Logic Model (PLM) mixed method | Clients and carers, program management, staff of the Consortium, and other partners and agencies, and clinical, allied health, and other service providers |

To evaluate the program two years after implementation | Staff -management open and transparent -Client and carers agreed that the staff was engaging them -All agreed that service offered a clear meaningful recovery program that is understood by all - Improved collaboration, communication, and clear referral channels among the team -All seemed to understand the recovery approaches and its language |

Origin: Australia Conducted: Australia Challenges Lack of understanding on what PIR Lack of facilitators in implementation, lack of peer engagement |

3. RESULTS

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) was used to select the articles. The PRISMA flow chart is an internationally recognised flow chart that pictorially gives a summary of the procedure followed to include and exclude studies in systematic reviews [24]. The PRISMA flow diagram above summarises the search and screening processes used to select the articles. 31 articles met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). A literature search was conducted, and 560 studies were identified through different databases. Ebscohost 68, (Cinahl (14), Academic Search (21), APA Psych Infor (24), Medline (6), APA Psych Article (3)), SABINET (196) and PubMed 296. After combining and removing all the duplicates, including one article written in French, 311 articles remained. The reviewers scrutinised the remaining articles' titles and abstracts and removed 254 articles that did not address the broader research question. 57 articles remained. Furthermore, 26 were removed after going through the full text of the remaining articles as they focused on something other than the recovery approach of people with serious mental illness, and eventually 31 remained.

3.1. Data Synthesis and Analysis

The results were analysed using content analysis. As a research method, content analysis systematically and objectively describes and quantifies phenomena [25]. The review results were manually coded and presented in a narrative format (Table 1).

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

Of the included studies, 15 were conducted on patients. They involved exposing or enrolling patients in a programme and, in the end, evaluating the programme’s effectiveness. Eight of these studies involved a comparative study where a particular programme that enrolled mental health users was compared with another or to those that were taking regular treatment. Three studies were conducted on staff members or others, and they involved training staff on a recovery programme, implementation, and evaluation. Four studies were conducted on staff, patients, families, and other mental health stakeholders. The remaining nine (9) studies involved implementing a recovery programme at the facility level and its evaluation by the combination of staff and patients or families or, in other studies, totaling 31 studies.

The results are based on the review's objectives, which were to describe the recovery-oriented mental health approaches, recovery-oriented mental healthcare programmes, the effectiveness of the recovery programmes and their challenges and the recovery-oriented programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. The results are summarised as follows: Recovery-oriented programmes, recovery-oriented mental health approaches, effectiveness and challenges of recovery-oriented programmes and recovery orientation approach in Sub-Sahara Africa.

3.3. Theme 1 Recovery-oriented Mental Health Programmes

The majority of studies selected were conducted in the United States of America (11), UK (4), Australia (5), Canada (2), Sweden (1), Ireland (1), Denmark (1), Netherlands (1), Portugal (1), South Korea (1), Norway (1), France (1) and Chile and Brazil (1). The mental health recovery programmes utilised in the studies selected mainly originated from Western Countries, as (Table 2) indicates below.

3.3. Theme 2: Recovery-oriented Mental Health Approaches

The recovery-oriented mental health approaches are reported from the perspectives of the patients, peers and staff members on what they believe recovery from mental illness entails.

3.3.1. Sub-theme 2.1 Description of Recovery

Recovery is often understood differently by staff and patients.

Table 2. Recovery programmes and their origins.

| Country | Programme |

|---|---|

| United States of America | Wellness Recovery Action Planning educational programme (WRAP), Self-Direction programme, Illness Management and Recovery (IMR) for people with serious mental illness, Person-Centred Care Planning (PCCP), Self-Direction program for people living with mental illness, Art Therapy Project, Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) programme, 'Housing First' approach, Consumer-run mental health services, Auto videography, Social Point” program-Social inclusion activities, Opening Doors to Recovery (ODR), Housing First (HF) program- with ACT, Pathways Housing First within the ACT. |

| Australia | Recovery Camp, Prevention and Recovery Care (PARC), Partners in Recovery. |

| United Kingdom |

Therapeutic Horticulture (TH) within Mental Health Recovery Programme, GetReal, Critical Time Intervention-Task Shifting (CTI-TS), Patient engagement, Intervention The Steps to Recovery (STR), Intermediate Stay Mental Health Unit (ISMHU) intervention, implemented within an Integrated Recovery Oriented Model (IRM), Four full-day workshops and in-team half-day session on supporting recovery. |

| Sweden | Recovery Guide for you-RG in inpatient care. |

| Netherlands | Training in Comprehensive Approach to Rehabilitation (CARe). |

3.3.2. Patients’ Perspectives

Six (6) studies involved enrolling clients in a recovery-oriented programme followed by its evaluation. 2 studies focused on skills improvement, the importance of self-care, self-management skills, fostering hope, and the value of peer support and emphasis on personal recovery. A study by Matsuoka [26] used the Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) programme to find the meaning of recovery for older Japanese-speaking Canadians diagnosed with mental illness. The study further sought to establish the applicability of the programme to them. WRAP is a framework healthcare workers use to learn more about mental illness and how to manage it from a recovery-oriented approach. Moreover, individuals with mental illness could use it to learn more about their condition and how to take control of their life. It is a tool that individuals can use to gain insight into and control their mental illness to facilitate their recovery process [27]. It can be tailor-made to the needs of a specific target group. The findings indicated that clients felt WRAP was helpful to them. They reported that they learned several things about themselves, felt hopeful for the future, and valued peer support in their recovery process despite having a diagnosis of mental illness. They felt empowered to negotiate things essential in their recovery that were not only focused on medication. Another study utilised the Steps to Recovery Programme (STR) on older people with mental illness health facilities [28]. STR programme is a group intervention where people with mental illness are provided with information about mental illness and recovery, including goals of recovery, hope for recovery, personal skills and for maintaining relations ships. Participants reported improved mental health and well-being. They valued the support and having relationships as vital to their recovery. They embraced the recovery concept as vital in their recovery process.

One intervention study utilised a Medication Free Programme (MFP) to demonstrate that people with serious mental illness can recover even without medication [29]. MFP is a programme whereby clients are offered alternative treatments other than psychotropic drugs to manage their mental health problems. Clients were given a choice to take medications. The study was conducted in Norway and aimed at describing users’ experience of their recovery process on a medication-free intervention. The results demonstrated that clients valued having choices on treatment as crucial to their recovery process. There was a general improved interpersonal relationship between clients and healthcare workers. In addition, the channels of communication between clients and staff improved.

Furthermore, two studies involved the intervention of self-determination involving people with mental illnesses enrolled in government-sponsored recovery programmes to empower them with accommodation and monetary budget to determine how they will manage their recovery process. One study in France involved an intervention whereby people with mental illness were provided with housing as part of their recovery [30]. Another involved people being given money to control their budget based on their recovery goals and plans [31]. The results demonstrated that people with mental illness view self-determination as part of their recovery process. The study by Croft et al. [31] indicated general improvement in the quality of life of people with mental illness following allocation of a house to stay in, a general reduction in hospital stay and improved self-esteem. The Croft and Parish study indicated that participants could meet their daily basic needs, which resulted in better clinical outcomes. The clients were able to use the money to seek the help of social workers and psychologists for better symptom management. Most clients worked towards their employment goals as they used the money to buy resources such as computers. They felt a sense of belonging as they could afford to pay for memberships in social clubs.

Another study in Canada compared the effectiveness of Housing First against treatment as usual in the recovery of people with serious mental illness [32]. HF is a recovery-oriented mental health service intervention that uses government funds in the USA to build and allocate homeless people diagnosed with mental illness houses as part of their treatment plan. Participants viewed having a house as an integral part of their recovery than homelessness. Participants reported general improvement in mental health, emotional and physical well-being, and relationships. In addition, owning a house brought a sense of hope for recovery and the future.

3.3.3. Staff Perspective and Peers' Perspectives

Stanhope et al. [33] conducted a study to find out the perspectives of case managers on the role of medication on clients with severe mental illness in supported housing recovery programmes and how their personal beliefs influenced treatment options for them. The findings reveal that the case managers of the housing programme found the treatment to be integral to the recovery of clients, and some suggested that it should be taken for life. In addition, treatment adherence was used as a sign of being house ready. Generally, case managers viewed clients who did not have insight into their illness as challenging to deal with and were not prioritised for housing.

Of the thirty-one (31) included studies, two (2) involved peer-supported recovery-oriented care. Lewis et al. [34] conducted a study to learn about consumer-run facilities' recovery features. Consumer-run facilities are mental health settings that are staffed and run by people who are users of mental health services. The peers are on government payrolls. The study utilised a modified ethnographic method and was conducted over ten (10) months. The results indicated that the staff and the users felt accountable for the welfare of each other. There was a sense of belonging and authentic connectedness among the staff and users. The staff and users often accompanied each other on job hunting, socialisation activities and community involvement. There was also accountability in the management of symptoms as they watched each other and monitored any signs of relapse. It could be said that recovery focused on support on relationships, employment, symptoms management and general accountability of each other's welfare in a non-judgemental setting.

Another study that involved peer support was the evaluation of an Open Door to Recovery (ODR) programme by [35]. ODR is a mental health recovery-oriented programme run by peers, social workers, and other mental health stakeholders such as multiple community partners and community navigators. The programme's main aim was to help the service users in their recovery programme. All those involved took part in the evaluation. The participants viewed the programme as helpful to their recovery. It brought the mental health personnel, service users, peers and community navigators closer to the central goal of helping clients recover. However, the significant weaknesses were slow implementation, lack of community and clinical services support, insufficient resources and devaluation of peers by clients and the community.

3.3.4. Facilitators of Recovery

Two (2) intervention studies involved patient engagement in a recovery programme to improve client recovery through team building and collaboration. One utilised Therapeutic Horticulture [36]. TH is where people with mental illness were involved in a gardening project to facilitate their recovery. The participants reported having confidence in themselves, improved social networks and relationships, developed new skills, and improved mental health and well-being. Another study utilised a recovery camp programme to improve collaboration and teamwork among people with mental health problems in Australia [37]. The clients reported improved self-confidence and relationships with themselves and others and felt empowered. The study demonstrated the potential for Recovery Camp as a facilitator for the recovery clients with mental illness.

Additionally, two studies, one from Canada Patient Engagement (PE) and another from Australia Partners in Recovery (PIR), were conducted to demonstrate patient engagement in a recovery-oriented approach. Patient engagement facilitates recovery and reduces stigma towards people with mental illness. PE, just like PIR, entails the involvement of service users, clients, peers, and carers of people with mental illness in the decision-making and daily running of mental health services. The two studies evaluated the effectiveness of patients and their partners in strategic committees and organisational functioning of the facilities as they fostered an inclusive environment that supported the recovery of patients [38, 39]. The two studies reported improved collaboration between staff and patients following patient engagement. Trankel and Reath’s [38] study reported that the PIR program was recovery-oriented and more engaging for patients, families, and peers. There was an improved understanding of the recovery principles and approaches. The staff and everyone involved seemed to understand the recovery process, and management supported the programme. Elwards et al.’s [39] study reported that managerial support and strong leadership were instrumental in implementing patient engagement programmes.

One patient study demonstrated the value of support by adapting the Critical Time programme in Brazil and Chile [40]. The intervention aimed to integrate people with mental illness in the community transiting from homeless shelters through the help of a paired community mental health worker and a peer support worker in Brazil and Chile. The participants valued the support from the mental health peer workers as they believed they helped them to reintegrate into the community. In addition, the participants identified with the paired workers more than regular mental health professionals. A minor setback was that some participants and their families were stigmatising peer workers as they could see that they were having symptoms of mental illness. Nevertheless, the intervention was welcomed by many, and they felt it could continue.

In Sweden, Bejerholm et al. [41] conducted a study intended to find the feasibility of implementing a recovery programme (Recovery Guide for you (RG)) for mental health staff. RG is a booklet with information which describes the recovery process touching on topics such as views on recovery, guidelines for the provision of recovery and treatment plans in the recovery approach. The staff perceived RG booklet as legitimate and acceptable. The staff could transfer knowledge gained to the care plans of the clients. The results of applicability of RG were acceptable.

3.4. Effectiveness and Challenges of Recovery-oriented Programmes

About 3 studies evaluated the effectiveness of the recovery programmes on patients with mental illness in their recovery process, focusing on their illness management and general well-being. Dalum et al. [42] utilised a randomised assessor-blinded multisite clinical trial on Illness Management Recovery (IMR) to compare it with treatment as usual on 200 people with mental illness. IMR is a curriculum-based intervention based on topics that explain mental illness from the context of a recovery approach. It focuses on symptom management, coping with stress, promoting healthy life struggles, reducing relapses, promoting healthy lifestyles, and encouraging personal recovery. The results showed no difference between the intervention and the control group. Another study by Linz et al. [43] introduced, implemented and evaluated the use of videography on clients with serious mental illness following graduation from a recovery-oriented programme. The study used a randomised controlled trial on 27 participants who were randomised into two groups, one group provided with videos to document their recovery process and the other serving as control. The findings revealed that videography was feasible for people with mental illness. The video offered participants a self-reflection on their fears, hopes for the future and recovery goals. The videos were also educative as they provided information about living with a diagnosis of mental illness. Videos have the potential to vouch for people with mental illness as they reflect on their needs, such as accommodation and equal treatment in society. The intervention was feasible and had the potential to be used in individual and group therapy sessions for people with mental illnesses.

One programme developed and evaluated for its effectiveness is PARC. PARC are residential recovery-oriented facilities that help people with mental illness from recurrent back-and-forth hospital admissions. The facility utilises a clinical model and recovery-oriented approach. Fletcher et al. [44] compared the services offered to a PARC facility in Australia on its operations and functionality, including resources. The managers of each facility were interviewed to solicit their views on the study's objective. The results indicated that all the facilities provided services in line with the Australian policies on recovery-oriented care. However, the facilities differed in structure and resources, and the services provided were contextualised to the community's needs and how the staff understood the recovery approach. Overall, the programme was found to be promising in providing recovery-oriented care. Hyeres et al. [45] also evaluated another PARC facility in Australia on services users, carers, and staff. The participants evaluated PARC as a functional recovery-focused model. The clients valued and appreciated the care provided by the staff.

Furthermore, the clients felt supported by all in the facility. Lastly, the staff reported feeling valued and appreciated by the clients. Overall, the programme was appreciated by all the participants.

One programme implemented on patients compared the effectiveness of a social inclusion programme intervention against treatment as a usual approach to the recovery of patients [46]. The social inclusion programme promotes the social participation of clients with mental illness by engaging them in community activities such as volunteerism, leisure engagement, mental health awareness campaigns and general promotion of mental health matters. Those in the social inclusion programme showed a high level of functionality, increased self-esteem, and reduced internalised stigma. The study provided evidence of the usefulness of social inclusion programmes in the recovery of patients.

There are two (2) included studies that evaluated the effectiveness of the recovery programmes on staff. Bitter et al. [47] investigated the effectiveness of the CARe methodology programme by training staff on managing mental illness. CARe approach to recovery involves improving the quality of life of people diagnosed with mental illness. It is built on reinforcing clients' strengths, improving connectedness with the client's environment, and helping them access their daily wishes. The investigation used RCT to compare two housing-supported facilities; one where the staff received CARe methodology training and the control, which continued treatment as usual. The results showed improvement in clients' quality of life after being cared for by staff who have undergone training.

Gilburt et al. [5] developed, implemented and evaluated a training workshop on staff across mental health facilities in London. The workshop comprised a four-day classroom set-up workshop, covering information on what constitutes recovery, and care planning from users' perspectives based on recovery principles underpinning the role of hope and clients' personal goals. The results indicated a buy-in to the training evidenced by good attendance, staff provided care reflective of recovery, the staff instilled hope in the clients, and they took ownership of the programme implementation. Generally, staff felt empowered to implement a recovery approach for service users. Another study by Bhanbhro et al. [48] evaluated the GeTREAL staff training recovery programme using realistic evaluation principles. The GeTREAL programme aimed at improving the staff's confidence and skills in caring for clients with mental illness. The results indicated that the staff were welcoming to the programme, happy to see the clients improving, trying new things with clients, and generally feeling empowered. However, the challenges experienced were a lack of support and other resources to implement the programme.

Other intervention programmes evaluated the effectiveness of programmes on different stakeholders in mental health facilities. For instance, Monroe-DeVita et al. [49] used a small-scale cluster RTC to assess the feasibility of implementing Illness Management Recovery (IMR) within ACT teams in two states in America. One team was just an ACT, and the intervention was ACT+IMR. The results showed the feasibility of implementing IMR within the ACT. Another study that implemented the feasibility of IMR within ACT was conducted [50]. The study utilised qualitative methods to solicit views on the implementation, staff training and barriers to implementation. The findings revealed that IMR enhanced the recovery goals of ACT. Clients' symptom management improved, and they understood their illnesses better. The staff reported improved skills in a recovery-oriented approach. The significant challenges were that it took a long time to learn and implement the IMR. There was also a general competition between work as usual with the implementation of IMR. However, the staff were challenged by the service users' symptoms when implementing IMR.

In Ireland, Higgins et al. [51] conducted a mixed method pre and post-study that evaluated the effectiveness of 2 and 5 days on the WRAP programme on service users, their families, and staff. The evaluation focused on knowledge, attitudes, and skills of using the WRAP programme following the intervention. All participants showed a high level of knowledge gained pre and post-training, resulting in improved attitudes and skills. In addition, all participants had confidence in the implementation of WRAP, and they all felt that they could train others on the programme.

Other studies provided evidence of implementing recovery in mental health facilities. A study by Choy-Brown et al. [52] sought an understanding of the multiple stakeholders involved in a recovery-oriented approach to service planning in a supported housing programme. The service plan uses a person-centred care planning approach that focuses on the client's individual needs and goals. It is based on a strength model that is collaborative and inclusive. The aim was to understand the multiple stakeholders' perspectives in implementing service planning in supportive housing. There was a consensus from programme planners and users that implementation rules were rigid as they did not support the recipients' goals. The services reminded everyone of the institutional plans and one size all model of care, which they believed was not recovery-oriented. A rigid organisational culture and lack of sponsor for the programme was seen as significant challenge to the programme implementation.

Frost et al. [53] evaluated the Intermediate Stay Mental Health Unit (ISMHN) services using multiple methods. The (ISMHN) in Australia is an Integrated Recovery Model concept. ISMHN is a 20 beds unit providing non-acute care to address the recovery needs of people with mental illness for a maximum of 6 weeks. They aim to provide remediation, reconnection and improve the overall quality of life. The programme is person-centred and embedded in the principles of recovery. The clients showed improvement in symptom management and functionality. Patients appreciated the services they received from the staff and valued the holistic and patient-supported approach.

Another study in Australia implemented and evaluated the use of ART therapy in a secure mental health facility [54]. The study sought the views of the managers, art therapists and patients on the use of Art therapy following the intervention. All participants reported that the intervention was beneficial. Patients gained participatory skills, cooperation, teamwork, and self-confidence. There was a general sense of belonging and relaxation experienced by service users who were in the programme, and they wanted more of the programme. Some challenges experienced included a general lack of support in implementing the recovery approaches from the managers, such as using the biomedical approach. In addition, there was also lack of funds for the programme.

Two studies compared the effectiveness of two recovery-oriented facilities. Salyers et al. [55] used an observational survey to compare the effectiveness of a high and low recovery orientation programme. Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams comprise a community-based group of mental health practitioners that facilitates patient recovery in a team approach. ACT teams' goals are person-centred and encourage the achievement of individualised client goals. The results indicated the same findings on illness management, hope for future optimism and general overall satisfaction. The highly rated recovery-oriented ACT team showed greater client involvement in their care. The evidence supports that ACT teams are recovery oriented.

Salyers et al. [56] also conducted a study comparing ACT teams' effectiveness and standard case management, which served as a control. The two approaches were compared on psychiatric symptoms of clients, global functioning, life satisfaction and recovery promotion among individuals with mental illness. ACT teams' service users showed a significant reduction in symptoms and global functioning. There was no difference in life satisfaction. ACT teams were established to be more supportive of the recovery approach compared to the control group.

4. DISCUSSION

The review aimed to explore the literature on recovery-orientated programmes in mental health in the Sub-Saharan context. Furthermore, it intended to bring to light mental health recovery-oriented programmes available, their origins, effectiveness, and challenges of implementing them. Unfortunately, no recovery-oriented mental health programmes were found in sub-Saharan Africa. In recent years, recovery in mental health and mental illness has been shaped by the experiences of those undergoing it. In addition, recovery is described as more of a process that goes beyond the cure of symptoms and the personal experiences of an individual shape it. Therefore, attempts have been made to support people with mental illness to make their recovery process as smooth, personal, and fulfilling as much as possible. This has been done by developing mental health recovery programmes geared towards supporting people with mental illness as they walk through their recovery process.

The review found 31 research articles on mental health recovery programmes that intended to improve the recovery of clients with mental illness. The studies also intended to improve the knowledge level of staff working in mental health facilities and families of people with mental illness, as they are instrumental in clients' recovery through their care and support. The majority of studies included in this study were from the USA (33.3%), Australia (18.18%), Canada (6.45), UK (12.90%), Europe (22.58%), South Korea (3.22%) and Brazil and Chile (3.22%). Most recovery-oriented programmes originated from Western countries, and none was identified in Africa. The results indicated the implementation of different programmes across countries, and other programmes that originated in the USA were tested and adapted in other countries. Most recovery programmes were developed and implemented in different settings and countries. This suggests that recovery programmes are contextualised according to the needs of the communities in different countries.

The findings indicate that although the implementation of recovery programmes met some challenges across countries, the programmes significantly improved the general well-being and quality of life of people with mental illness. Studies have described what recovery from mental illness means and the factors that facilitate it. They described having a sense of belonging, connection through different channels, community participation, house ownership, hope, and a general feeling of being in control of their life as essential steps and facilitators of their recovery. Literature in recovery studies has consistently referred to patient empowerment, self-determination, connectedness, having hope for the future and living a life that is personally fulfilling with or without symptoms of mental illness as factors that are essential in the recovery of people with SMI [57, 58]. On the other hand, some staff members have alluded that good patients' insight about their illness and the use of medication adherence are essential ingredients for the recovery of clients with mental illness. In addition, others have suggested that people with mental illness must take treatment for life once diagnosed with mental illness. Insight involves processes of awareness or recognition of signs and symptoms of illness and attribution or explanations about the cause or source of these signs and symptoms [59]. In addition, insight includes the recognition by a person diagnosed with a mental illness to take and adhere to treatment as prescribed [60]. Studies on healthcare workers' perceptions of insight and mental health recovery attached having good insight as the first step in recovery from mental illness. They believed that if clients had good insight, they would comply with treatment, which could greatly facilitate their recovery [61]. Studies have established a link between insight and adherence to the treatment of clients [62, 63]. An editorial by Reddy [64] categorised insight as a critical factor in clinical psychiatry. It could facilitate clients' willingness to take treatment, leading to better clinical outcomes for their mental illness. Therefore, adherence to medication by patients should be part of the treatment plan for clients with mental illness [65]. On the other hand, it is argued that medication is just one of the facilitators of recovery, as people with a mental illness can recover with or without it [66]. This argument is fostered by the perspective that encourages the care approach in mental health that looks beyond an individual's symptoms, focuses on capacitating resilience, and offers patients support [3].

Facilitators of recovery in this review have been identified from the perspective of the service users, staff, and mental health peers. The values of support from families, peers, staff, and other mental health workers are paramount to the service users in their recovery. The education provided to the service users, staff and their families was instrumental in helping the individuals deal effectively with their mental illness. The staff could also give improved care to the service users following the skills gained from the educational programmes they attended. This finding highlights the value clients attach to receiving care from peer-run mental health facilities.

Peers as the users of mental health services offered the clients non-judgemental mental healthcare, giving them a sense of hope through the shared array of activities they did for and with the clients. This included being accountable for one another, accompanying each other in employment sleeking endeavours and patient engagement through community participation. As a result, clients felt more at home with a peer-run facility. The results indicated that there was a general buy-in to implementing peer-run facilities recovery programmes. This could be so because most Western countries have policies that support the recovery approach [5, 10, 11, 67]. Most studies on intervention and evaluation of programmes for patients and staff have found significant improvements. However, two studies did not find any change or difference when the mental health recovery programmes were compared with treatment-as-usual programmes. It could have indicated that most facilities, especially in Western countries, view themselves as offering holistic, integrated care and not as different from the recovery approach [68]. Other factors could be that most countries have endorsed the recovery approach, making it difficult to differentiate from care as usual [67, 69, 70]. In another study, a suggestion was made that sample size could be the reason for a failure to see the difference when the programmes were compared with treatment as usual.

In implementing the recovery, even though they showed that they worked for people with mental illness, they also faced some challenges. Most of them had problems with funding and a shortage of staff to implement. Additionally, other facilities reported a lack of understanding of the recovery approach and how to differentiate it from the usual practice. Organisational policies and regulations were also rigid, and staff were bent on the existing rules to provide patient care than implement the recovery approach. As a result, the staff were torn between their routine work and implementing the recovery approach. Furthermore, there were indications that mental health peer workers were stigmatised by professional mental healthcare workers and the community when doing their job. Findings are supported by Ørjasæter & Almvik [71] in their study on the challenges of adopting recovery-oriented practices in specialised mental healthcare. The study identified factors such as the rigidity of mental health personnel towards recovery approach, existing policies, the disease model prevention, and cure perspective of managing illnesses and the legal dilemmas of practice as challenging implementation of the recovery-oriented approach. As a result, the study recommended that adopting a recovery-oriented approach must be accompanied by a change in policies and existing management protocols of patient care and a change in mental health professionals' mindset. Despite all these challenges, the recovery programmes showed a significant effect in managing people with mental illness.

5. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The study provided a broader perspective on the recovery approach and how it is implemented in people diagnosed with mental illness. However, the review is limited as it did not consider the design used to conduct the study since it did not fall within the ambit of the study. In addition, the review was limited to articles found and included at the time of selection of the studies. No studies in Sub-Sahara Africa described implementing a recovery-oriented mental healthcare programme when selected articles were found.

CONCLUSION

The objective of the review was to explore the global literature on recovery-oriented mental healthcare programmes on where they originate, their implementation and effectiveness, as well as identify gaps in literature for further research. The review demonstrated that most recovery mental healthcare programmes were from Western high resourced countries, and they had proven to be effective and appreciated by the people diagnosed with mental illness. At the time of the review, no study was found that demonstrated a recovery-oriented mental healthcare programme in Sub-Sahara African context. Therefore, there is a need for African countries, for example, Botswana, to develop their own recovery oriented mental health programmes in order to support people diagnosed with mental illness.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to this manuscript submitted for review. KMK conceptualised the manuscript as part of her PhD study. The two study supervisors ME and PMS provided guidance and the final critical revisions and editing of the manuscript. All the authors proofread the article before submission.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| PRISMA | = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| MMAT | = Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

| WRAP | = Well-ness Recovery Action Plan |

| MHS | = Mental Health Services |

| ROP | = Recovery-Oriented practice |

| CARe | = Comprehensive Approach to Rehabilitation |

| PCCP | = Person Centered Care Planning |

| PARC | = Prevention and Recovery Care |

| ISMHU | = Intermediate Stay Mental Health Unit |

| HF | = Housing First |

| ACT | = Assertive Community Treatment |

| ODR | = Opening Doors to Recovery |

| STR | = Steps to Recovery |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The scoping review was part of the PhD study which was approved by the North-West University Health Research Ethics Committee (NWU-HREC). No: NWU-00306-21-S1.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines and methodology were followed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the librarian and the North West University School of Nursing for the workshops and webinars they provided on systematic and scoping reviews.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

PRISMA checklist is available as supplementary material on the publisher’s website along with the published article.

REFERENCES

| [1] | Andresen R, Oades L, Caputi P. The experience of recovery from schizophrenia: towards an empirically validated stage model. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2003; 37(5): 586-94. |

| [2] | Leamy M, Bird V, Boutillier CL, Williams J, Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry 2011; 199(6): 445-52. |

| [3] | Jacob KS. Recovery model of mental illness: A complementary approach to psychiatric care. Indian J Psychol Med 2015; 37(2): 117-9. |

| [4] | Dell NA, Long C, Mancini MA. Models of recovery in mental illness. Social Science Protocols 2020; 3: 1-9. |

| [5] | Gilburt H, Slade M, Bird V, Oduola S, Craig TKJ. Promoting recovery-oriented practice in mental health services: a quasi-experimental mixed-methods study. BMC Psychiatry 2013; 13(1): 167. |

| [6] | Palmer W, Gunn. Recovery from severe mental illness. CMAJ 2015; 187(13) |

| [7] | Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehabil J 1993; 16(4): 11-23. |

| [8] | Collier E. Confusion of recovery: One solution. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2010; 19(1): 16-21. |

| [9] | Australian Department of Health. Recovery Oriented Service Delivery 2021. Available from: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs-n-recovgde-toc~mental-pubs-n-recovgde-5#:~:text=Recovery-oriented%20mental%20health |

| [10] | Parkin S. Salutogenesis: Contextualising place and space in the policies and politics of recovery from drug dependence. Int J Drug Policy 2016; 33: 21-6. |

| [11] | Slade M, Amering M, Farkas M, et al. Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry 2014; 13(1): 12-20. |

| [12] | Lavallee LF, Poole JM. Beyond Recovery: Colonization, Health and Healing for Indigenous People in Canada. Int J Ment Health Addict 2010; 8(2): 271-81. |

| [13] | World Bank Indicators Data Base. Gross Domestic Products GDP data source. 2015. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalogue/world-development |

| [14] | Maiga DD, Eaton J. A survey of the mental healthcare systems in five Francophone countries in West Africa: Bénin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Niger and Togo. Int Psychiatry 2014; 11(3): 69-72. |

| [15] | Bila NJ. Social workers’ perspectives on the recovery-oriented mental health practice in Tshwane, South Africa. Soc Work Ment Health 2019; 17(3): 344-63. |

| [16] | Chorwe-Sungani G, Namelo M, Chiona V, Nyirongo D. The Views of Family Members about Nursing Care of Psychiatric Patients Admitted at a Mental Hospital in Malawi. Open J Nurs 2015; 5(3): 181-8. |

| [17] | World Population Review. Middle Income Countries. 2022. Available from: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/middle-income-countries |

| [18] | Hinga BW. Examining mental health policies in Botswana. 2021. Available from: https://borgenproject.org/mental-health-in-botswana/ |

| [19] | Maphisa M. Mental health legislation in Botswana. BJPsych Int 2018. |

| [20] | Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2018; 18(1): 143. |

| [21] | Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice 2005; 8(1): 19-32. |

| [22] | Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’ Brien K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 2010; 5: 1-69. |

| [23] | Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, et al. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 User guide. Department of family. Medicine 2018. |

| [24] | Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews(PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and ExplanationThe PRISMA-ScR statement. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169(7): 467-73. |

| [25] | Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, Pölkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngäs H. Qualitative content analysis. SAGE Open 2014; 4(1) |

| [26] | Matsuoka AK. Ethnic/Racial Minority Older Adults and Recovery: Integrating stories of resilience and hope in social work. Br J Soc Work 2015; 45(1)(Suppl. 1): i135-52. |

| [27] | Copeland ME. Wellness Recovery Action Plan 2002. |