All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Self-Reorientation Following Colorectal Cancer Treatment – A Grounded Theory Study

Abstract

After colorectal cancer (CRC) treatment, people reorganize life in ways that are consistent with their understanding of the illness and their expectations for recovery. Incapacities and abilities that have been lost can initiate a need to reorient the self. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have explicitly focused on the concept of self-reorientation after CRC treatment. The aim of the present study was therefore to explore self-reorientation in the early recovery phase after CRC surgery. Grounded theory analysis was undertaken, using the method presented by Charmaz. The present results explained self-reorientation as the individual attempting to achieve congruence in self-perception. A congruent self-perception meant bringing together the perceived self and the self that was mirrored in the near environs. The results showed that societal beliefs and personal explanations are essential elements of self-reorientation, and that it is therefore important to make them visible.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide among both females and males. About 1.2 million cases of CRC were registered in 2008, which is approximately 10 percent of all new cancer cases globally. It is predicted that the number of cases will rise to 2.2 million worldwide by 2030 [1]. CRC is treated with surgery, and radiation and chemotherapy are additional treatments. General symptoms after treatment are unpredictable and include irregular bowel function [2], fatigue [3] and, if a stoma has been established, stoma-related symptoms such as leakage and skin irritation may occur [4]. The period after treatment may also include crisis responses triggered by having a life-threatening disease, such as depression and anxiety about cancer relapse, and psychosocial difficulties such as reduced social activity due to being treated differently by family and friends or due to experienced symptoms [5].

Qualitative studies describing how persons treated for CRC experience recovery have portrayed this period as a time when the body makes the rules [6], initiating a process of recapturing lost bodily control and restoring the relationship with the body [7]. This period is also depicted as a time when symptoms influence emotional functioning. Fear, anxiety and vulnerability based on unpredictable bowel function, especially fecal incontinence [8] and persistent problems with dietary intake, cause loss of one’s former adult identity [9].

Before illness occurs, most people take their health and bodily function for granted, and thus no longer being able to rely on the body’s ability may create a threat to the self [10]. The focus on incapacities and abilities that have been lost can initiate a need to reorient the self [11, 12]. Recovery after CRC surgery has previously been described by Beech et al. (2011) as a process of restoring the self by alternating between a sense of wellness and a sense of illness [13]. The concept of the self may be understood in terms of different dimensions including both a personal self that is an idiosyncratic dimension of self – a highly personal and individual understanding and meaning of self-perception – and a social self – the interpersonal being and the result of the influence of interaction on self-perception. From a sociological perspective the social self may be viewed as a product of social interactions [14].

People choose to behave and reorganize life in ways that are consistent with their understanding of an illness and their expectations for recovery [12]. Understanding of illness is dependent on the perception and interpretation of illness, which involve a person’s thoughts about the etiology of the disease, about the disease being acute versus chronic, and about his/her own ability to control and manage the consequences of the illness experience [15]. This interpretation of the disease is the first stage in the self-regulation model of compliance with illness developed by Leventhal and colleagues [12]. The model is built as a structure with three stages: interpretation, coping and appraisal. The interpretation of the disease creates a mental representation of the illness. Based on this illness representation one or several coping strategies are selected. Finally, appraisal of these actions provides feedback that influences both the representation of the disease and the plan of action itself [12]. Even though Leventhal’s self-regulation model of compliance does not explicitly invoke the self [12, 11] this model may still influence how the self is perceived among treated persons.

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have explicitly focused on the concept of self-reorientation after CRC treatment. The aim of the present study was therefore to explain self-reorientation in the early phase of recovery after CRC surgery and to explore how illness perceptions, symptoms and expectations for recovery influence this process of self-reorientation.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Design

Grounded theory gives the opportunity to explore self-reorientation through interpretation and abstraction [16]. The present study is pursued using a postmodern methodology, which recognizes the roots of symbolic interactionism as a dynamic theoretical perspective that views human action as constructing the self, the situation and society, and given this interpretative focus, we see ourselves as both part of and as influencing the world we study. To remain consistent with the chosen theoretical perspective and methodology, we have used the method presented by Charmaz (2006) [16].

Selection of Participants

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Gothenburg (Reg. no. 753-10). Participants were recruited from colorectal cancer patients who participated in an ongoing survey study at a county hospital in western Sweden. Interviews were conducted three to nine months after surgery to reflect the period of early recovery – all interviews were conducted during the nine-month period from October 2011 to June 2012. The selection of participants was carried out so as to achieve sample variation regarding diagnosis (colon versus rectal cancer). Participants were informed about the study and invited to participate by phone. Seventeen out of the twenty-two asked were interested in participating and received a written letter with information on the aim and conditions of the study together with contact information. Written informed consent was returned by mail prior to the interview or was handed over in person on the interview occasion. Interviews were always conducted at the participants’ convenience either at their home, a neutral place or at University. Phone interviews were conducted in seven cases when participants were unable to meet in person due to poor health. In four cases partners attended at the participants’ request. For characteristics of participants see Table 1.

Characteristics of participants.

| Participants | Sex | Age | Diagnosis* | Stoma** | Chemo*** | Radiation**** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 61 | C | N | N | N |

| 2 | F | 62 | C | N | N | N |

| 3 | F | 73 | C | N | Y | N |

| 4 | M | 80 | C | N | N | N |

| 5 | F | 79 | R | Y | N | Y |

| 6 | F | 75 | R | Y | Y | N |

| 7 | F | 85 | R | Y | N | N |

| 8 | M | 77 | C | N | N | N |

| 9 | M | 85 | C | N | N | N |

| 10 | F | 75 | R | Y | N | Y |

| 11 | F | 67 | R | Y | N | Y |

| 12 | F | 68 | R | N | N | Y |

| 13 | F | 74 | R | Y | N | Y |

| 14 | F | 75 | R | N | N | Y |

| 15 | F | 74 | C | N | N | N |

| 16 | M | 71 | R | N | N | N |

| 17 | M | 85 | C | N | N | N |

* Diagnosis: R=Ca Recti; C= Ca Coli. **Stoma: Y=Yes; N=No. ***Chemo: Y=Yes; N=No.

****Radiation: Y=Yes; N=No.

Data Collection

One opening question was created – Can you describe an ordinary day and what it is like for you? – followed by questions on the cancer disease and symptoms such as: What do you think about the disease today? Do you have any symptoms? And probing questions such as: Can you describe what you think when this occurs? What do you feel? What do you do? How has this affected you? [16]. Each interview lasted between 30-60 minutes and was recorded digitally.

Data Analysis

Transcribing and initial coding were carried out in parallel with interviewing. Interviews were coded line by line and paragraph by paragraph while remaining close to the data and keeping the codes active by writing them as gerunds. During this phase, early memos were written containing ideas that came to mind during the initial coding as well as after the interview was done. At this point, the aim was not to censure any ideas, but to keep memos free. However, early connections were made and properties, such as when the process changed and the consequences of changing, were described. Constant comparative methods were used and interviews were compared with interviews and codes with codes, using memos to make sense of the material. This approach enabled the codes to be raised above direct interpretation, moving the analyses into the area of focused coding, where codes were interpreted by applying sensitizing concepts and theoretical sensitivity, which allowed the most significant codes to synthesize larger segments of data, while the properties of the codes were explained in memos. The researchers’ preconceptions were dealt with through focused, free writing about the data as well as knowledge and thoughts. Further, some codes were raised to conceptual categories by synthesizing themes of several codes into subcategories. Relationships between categories were clarified by clustering and comparing, and at the later phase of analysis two final interviews were conducted, aimed at refining the properties of the categories, i.e., theoretical sampling [16]. After theoretical sampling, clustering and comparing, the core category had taken shape, and the analysis was considered complete, as the researchers were no longer able to make progress. Nvivo was used to organize and categorize the data throughout the analysis procedure [17].

RESULTS

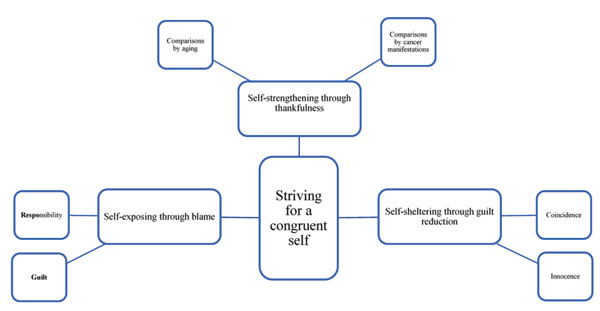

The present results explain self-reorientation as the individual attempting to achieve congruence in self-perception. A congruent self-perception means bringing together the perceived self and the self that is mirrored in the near environs. The present results describe self-reorientation in the early recovery phase in terms of the content of the core category striving for a congruent self and the conceptual categories self-strengthening through thankfulness, self-sheltering through guilt reduction and self-exposing through blame, as shown in Fig. (1).

Illustration of self-reorientation following colorectal cancer treatment.

The core of self-reorientation consists of cumulative questions that are impossible to answer unambiguously. Not knowing why the body reacts in a certain way and not knowing what caused the disease in the first place means being in a body and in a life situation that no longer feels safe and predictable. Losing one’s feeling of being able to predict the next minute, hour and day is interpreted as losing one’s expectations and the sense of self one once had. The person is placed in limbo with a self-perception that is no longer coherent and recognizable. The core category, striving for a congruent self, is presented through various attempts to get answers through personal explanations when no clear answers can be given. These attempts are described in the conceptual categories of self-strengthening through thankfulness, self-sheltering through guilt reduction and self-exposing through blame, illustrating different but simultaneously occurring strategies during early recovery.

Self-Sheltering Through Thankfulness

Expressing thankfulness was associated with the perception of aging as well as the widespread societal perception of how a person with cancer should feel, look, act and respond. These perceptions lower expectations for life in general and for health and activity in particular and somehow produce the need to express thankfulness for everyday life, no matter what everyday life looks like.

Comparisons by Aging

Symptoms were largely described as being connected to health problems due to old age or as a consequence of old age in general. Experiencing symptoms and obstacles in daily life became normalized and expected. This way of using age emerged by examining and comparing different reasoning and explanations concerning the treatment given and daily life experiences. Age served as an explanation that enabled positive comparisons, which both maintained and defended the perception of self as being the same as before the cancer made its debut. Feelings such as loss of vitality, depressed mood, and tiredness were explained, understood and accepted to a great extent as being due to age.

‘I guess I’m more tired than usual but it’s age too’ (8, Man, 77)

‘Then I’m getting older and that takes its toll. I’m 73 now so a lot has happened to this body after so many years’ (15, Woman, 74)

‘But I think that with age you start, well I value the small things in life more and more actually... I’m simply thankful’ (1, Woman, 61)

Age, when used as a factor for comparison, seems to increase understanding and acceptance of the experienced situation. There is an acceptance, tolerance and almost an expectation of cancer disease as a consequence of aging, which emerges when comparisons are made with younger persons with cancer.

‘All of these young people. I’m thinking about Sofia, how old is she, 30, and has breast cancer. And that’s worse than anything else’ (13, Woman, 74).

The age factor and its importance for making favorable comparisons and increasing feelings of thankfulness were further clarified by the participants’ awareness of waiting lists for examinations and treatment, and the widely held societal belief that the elderly receive low priority in cancer care. Actually receiving treatment and not having to wait longer than anyone else became a positive surprise.

‘It all went pretty quick. But still people say so much about medical care and waiting times and all that, that they don’t care about older people. But that wasn’t true in my case’ (17, Man, 85).

Comparisons by Cancer Manifestations

There is a strong societal belief that cancer and cancer treatment are highly visible on the outside and that people with cancer feel continuously ill. When such beliefs about how cancer should manifest itself do not fit the reality of cancer as perceived and represented among the participants, it sometimes lead to questions about whether or not there was any cancer.

‘I’ve felt fine the whole time. Nobody could look at me and see I was sick’ (16, Man, 71 ) ‘Everybody says you don’t look ill and I say, no, I’m not either’ (3, Woman, 73)

‘Actually I don’t feel bad’ (6, Woman, 75)

Comparisons made about treatment are another example of using comparisons of cancer manifestations in a favorable way. These comparisons are also made in order to increase the feeling of being lucky and blessed.

‘... I shouldn’t complain, I’ve seen so many others with much worse problems’ (3, Woman, 73).

‘Women with breast cancer they’re much worse off than me... their treatment is worse ....’ (6, Women, 75).

‘So many of them had a stoma.... and many got infections, it was like ... Well, it all went well both at the hospital and everything....’ (17, Man, 85).

Self-Sheltering Through Guilt Reduction

The participants commonly reported not understanding the cause of their cancer. This caused them to wonder and search for possible explanations. This conceptual category – self-sheltering through guilt reduction – constitutes freedom from guilt and was developed from the categories coincidence and innocence.

Coincidence

Coincidence rests on beliefs about commonality, where colorectal cancer is viewed as a frequently occurring cancer disease. Coincidence and the commonality of the disease gave the participants something to hold on to, it gave consolidation. Coincidence reduced guilt about being ill and allowed participants to refer to bad luck in general. Above all coincidence reduced their own feelings of responsibility for the disease.

‘It’s chance. Some get it some don’t. Some get one kind, others another and I’m as likely to get it as anyone else’ (12, Woman, 68).

‘But there are so many... it’s crazy... yes, really crazy... my God there are so many ... and I thought I was alone but...’ (6, Woman, 75).

Innocence

The importance of being innocent for reducing feelings of guilt was made visible by referring to the factor of heredity, which allowed participants to refer to bad luck, particularly regarding their genetic make-up. Genetic inheritance was seen as given, as something beyond one’s own control. The innocence brought by heredity reduced their own feelings of responsibility for the disease, offering self-shelter in a similar way as coincidence did.

‘... and Daddy had cancer you know and died of it and I’ve been wondering when it would get me’ (13, Woman, 74).

‘Both my parents died of cancer... so somehow I see a parallel there. After all there are people in my family who’ve had cancer...’ (10, Woman, 75).

Self-Exposing Through Blame

There is content in the participants’ statements that can be defined by the categories guilt and responsibility. These categories reveal a search within one’s own personal lifestyle when coincidence and innocence no longer provide sufficient long-term explanations. This content concerns issues connected to controllable lifestyle factors. Guilt and responsibility were interpreted as painful and as affecting self-perception.

Guilt

The issue of lifestyle factors as a possible cause was, unlike the notion of genetic inheritance or commonality, dependent on one’s own actions. Diet issues and the possibility of avoiding cancer through new diet programs are frequently occurring in magazines and in the news. Speculations regarding whether one has lived a sufficiently healthy life and one’s food choices were sometimes sources of self-blame. The search for explanations in food choices was thus interpreted as a consequence of the idea that people are ultimately responsible for their own health and illness. When one has lived what one considers a healthy life, this societal idea created importunate feelings of guilt that shook the very foundation of self-perception and the notion of oneself a responsible person.

‘Of course if I’d smoked and got lung cancer then I’d have known that there’s a reason, but I haven’t eaten a whole lot of sweet stuff and I haven’t been overweight.... but still what you eat can affect you...’ (12, Woman, 68)

‘I’ve almost been a vegetarian.... but in any case I’ve eaten healthy food and not prepared food but homemade. And you’d think eating like that would mean you’d lived soundly.... but of course now and then you eat a bag of candy or something and that’s not good…’ (10, Woman, 75).

‘What I think about is whether I’ve eaten the wrong foods. I’ve got no way of knowing’ (17, Man, 85)

Responsibility

Feelings of guilt and self-blame were interpreted as progressing and transforming to a dejected sense of responsibility during periods when commonality or inheritance could no longer give sufficient and logical explanations for why the bowel cancer had developed. This was particularly prevalent in second-time illness. When cancer developed the second time around, coincidence and innocence no longer served as a probable explanations regardless of how common the disease may be. Becoming ill again therefore brought about the need to face life-style choices and also to prepare oneself for future cancer illness.

‘You know I got cervical cancer 33 years ago and that’s a long time ago. But I didn’t think I’d ever get it again. So now I have no faith that I won’t get cancer again. It can be anywhere. Probably my lungs since I’m a smoker’ (11, Woman, 67).

DISCUSSION

The core of self-reorientation consists of cumulative questions that have inaccessible answers. These answers provoke different attempts to obtain unequivocal answers, as described in the conceptual categories: self-strengthening through thankfulness, self-sheltering through guilt reduction and self-exposing through blame. The categories illustrate different strategies used to escape incongruence in self-perception during early recovery. The reason for the strategies in the self-reorientation process was understood as being dependent on unanswered questions, which were based on beliefs and personal explanations that we call illness perceptions. These perceptions are grounded on information from different sources in cultural contexts that are influenced by social background, healthcare environment, etc. Illness perceptions illuminate the person’s understanding of the disease, such as thoughts about the etiology, expectations concerning the permanence of the disease and one’s ability to manage the consequences of it [15]. In previous studies, illness perceptions have been shown to be of relevance to expectations for recovery [18] and disease outcome [19-21]. Illness perceptions are partly a product of social interaction, which influences self-reorientation and self-regulation. The findings may therefore be further conceptualized by the looking-glass self, a theory introduced by Charles Horton Cooley (1983), suggesting that our perception of ourselves molded through previous social interactions shape our perception of others’ perceptions and assessments about us, which in turn regulate our concept of ourselves [22].

The core of the self-reorientation as presented here has a common denominator with findings presented by Beech et al. (2011) [14]. They described patients striving for a congruent self-perception in phases called a repairing self and a restoring self, which took place during the first year of recovery after colorectal cancer. The common denominator of the study by Beech et al. (2011) [13] and the present study is the need for answers expressed by the participants. Other studies on colorectal cancer survivors have also acknowledged informational needs as a problem, showing that treated persons request support from healthcare during the first year of recovery, especially the time after discharge from hospital [9, 13, 18]. The present results, however, further illuminate the importance of acknowledging illness perceptions and societal beliefs when giving support.

The strategies found in the self-reorientation process are described by the content of the conceptual categories “self-strengthening through thankfulness”, “self-sheltering through guilt reduction” and “self-exposing through blame”. The key to thankfulness in “self-strengthening through thankfulness” was the perception of an aging person as someone for whom disease and ailments were a natural part of life and for whom a lower level of activity was expected. Similarly, there was the perception of a person with cancer as someone who is suffering physically and mentally and who is marked by symptoms such as severe fatigue, loss of appetite and weight. The results showed that beliefs about cancer manifestations sometimes led to questions about whether or not the cancer had actually been present given that bodily manifestations did not occur as anticipated. This situation is a phenomenon that has previously been acknowledged by Ohlsson-Nevo et al. (2011) [6], who showed that an unexpectedly gentle recovery did make the cancer feel unreal.

Beliefs about cancer manifestations and aging enabled favorable comparisons, which in turn produced expressions of thankfulness by lowering hopes for health and activity. By using the strategy of comparisons in the self-reorientation, the perception of self is interpreted as being protected and made coherent through expressed feelings of thankfulness. This interpretation is in line with ‘the looking-glass theory’ [22], meaning that the participants have accepted societal beliefs about aging persons as part of their self-image, thus producing the need to express thankfulness. The need to express thankfulness may serve as additional knowledge that complements the quality of life estimates made by cancer survivors in studies by Arndt et al. (2004) [23] and Jansen et al. (2011) [24], which showed that persons over 60 report better quality of life on short-term follow-ups than younger persons do. Could it be that these self-reports showing better quality of life sometimes reflect estimates of thankfulness among older adults? Given that the age range of the respondents in the present study (61-85 years) corresponds to the age range in the above-mentioned studies, the question may be legitimate to raise, especially considering that age has previously been pointed out as a reason for dismissing needs [13].

The question of the cause of the cancer led to alternating strategies presented by the content of the conceptual categories “self-sheltering through guilt reduction” and “self-exposing through blame”. Alternating between a preserved, coherent self-perception and an unprotected, disrupted self-perception was understood as being torn between having caused the disease and being a victim of unfortunate circumstances. This interpretation is also in line with Cooley’s theory (1983) [22], according to which people shape their self-perception to fit what they believe are societal expectations. By referring to coincidence and the conviction that CRC is a frequently occurring cancer disease, feelings of responsibility for the illness were reduced. This prevented stigmatization based on the societal belief that people ultimately are responsible for their own health and illness. The strategy of stating that coincidence was a cause was understood as preserving the self and allowing the self to remain coherent during self-reorientation. The self was also understood as being shielded from harm by the content of “self-sheltering through guilt reduction” in contrast to the content of “self-exposing through blame”, where the self was interpreted as being unprotected from the societal belief that people are ultimately responsible for their own health and illness. The latter was a painful and disrupting strategy of self-reorientation, but it was also understood as necessary for taking charge over possible reoccurrences.

One limitation of the present study was subject selection, in that females are overrepresented. This may have affected the results, considering previous findings on gender differences, particularly one study showing that women experience more side effects after colorectal cancer than men do [25]. Another limitation is the use of phone interviews, considering that the core of the method is the notion that knowledge is constructed in interaction [16]. Phone interviews are considered useful for short and structured interviews [26, 27], and use of telephone interviews in qualitative research is consequently rare [28]. In situations when face-to-face interviews were impossible, participants were given the choice of participating in a phone interview instead. Providing this choice allowed a wider variety of participants to participate. It has also been shown to give more information overall, as well as information from people whose voices would not otherwise be heard [28, 29]. Sensitive topics may also be easier to talk about in relative anonymity [30]. Respecting the participants‘ wishes and considering their integrity and convenience are necessary from an ethical perspective as well as for promoting participation and access to rich data. The same reasoning applies to allowing partners to attend the interviews when the participants requested their presence.

Trustworthiness and Rigor

The strength of the study lies in the methodology. The systematic and constant comparisons made throughout the analysis allowed the empirical data to be fully covered by the categories presented in the results. The quotes work as a logical and visible link between the analysis and the data gathered (credibility). The present results offer insights into what self-reorientation after CRC treatment could be and how illness perceptions, symptoms and expectations for recovery influence this process (originality). The analysis of the self-reorientation process presented here may also offer new insights for people sharing the experience of CRC (resonance) and inspire researchers to further explore and explain the self-reorientation process in relation to other diseases (usefulness).

The literature review for the present study began when the conceptual categories and their relationships were considered to be complete, as recommended in this method [16]. The size of the present study makes the conceptual categories presented theoretically sufficient, but not necessarily saturated [16, 31]. Preconceived ideas are influential and undeniable, owing to the sensitizing concepts, preunderstandings, theoretical sensitivity and the abductive approaches to the conceptual categories [16]. Discussions of the analysis on a regular basis have been used here as one way to increase awareness.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

The present results explain self-reorientation as the individual attempting to achieve congruence in self-perception. The core of self-reorientation consists of cumulative questions that have inaccessible answers, which reveals the importance of acknowledging illness perceptions and societal beliefs when providing support. The exploration of illness perceptions, symptoms, and expectations for recovery showed that societal beliefs and personal explanations are essential elements of self-reorientation, and that it is therefore important to make them visible. The results of the present study also indicated that there is an unmet need for person-centered information and support within the first year after discharge from hospital. A simple voluntary nurse-led follow-up that provides answers to questions could ease patients’ uncertainty and facilitate their self-reorientation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Anna-Lisa and Bror Björnsson Foundation.