All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Making Each Other’s Daily Life: Nurse Assistants’ Experiences and Knowledge on Developing a Meaningful Daily Life in Nursing Homes

Abstract

Background

In a larger action research project, guidelines were generated for how a meaningful daily life could be developed for older persons. In this study, we focused on the nurse assistants’ (NAs) perspectives, as their knowledge is essential for a well-functioning team and quality of care. The aim was to learn from NAs’ experiences and knowledge about how to develop a meaningful daily life for older persons in nursing homes and the meaning NAs ascribe to their work.

Methods

The project is based on Participatory and Appreciative Action and Reflection. Data were generated through interviews, participating observations and informal conversations with 27 NAs working in nursing homes in Sweden, and a thematic analysis was used.

Result

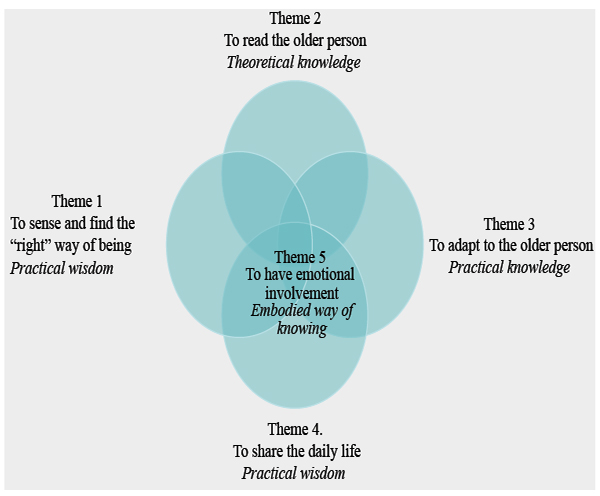

NAs developed a meaningful daily life by sensing and finding the “right” way of being (Theme 1). They sense and read the older person in order to judge how the person was feeling (Theme 2). They adapt to the older person (Theme 3) and share their daily life (Theme 4). NAs use emotional involvement to develop a meaningful daily life for the older person and meaning in their own work (Theme 5), ultimately making each other’s daily lives meaningful.

Conclusion

It was obvious that NAs based the development of a meaningful daily life on different forms of knowledge: theoretical and practical knowledge, and practical wisdom, all of which are intertwined. These results could be used within the team to constitute a meaningful daily life for older persons in nursing homes.

INTRODUCTION

It is essential that older persons experience a meaningful daily life even if they are in need of care. However, shortcomings have been reported in the care of older persons globally [1]. In Sweden, where municipalities are responsible for providing home care and long-term services for the elderly [2], shortcomings concerning staff’s values and attitudes have also been reported [3]. Additionally, older persons’ ability to influence the content and design of their own care is described as limited [3]. The Swedish government has therefore introduced national guidelines comprising of core values and local guarantees of dignity for the care of older persons. These guidelines highlight the need for care focusing on dignity and the older persons’ well-being, helping ensure they perceive their daily life as meaningful. Thus, staff has a responsibility to arrange older persons’ care in such way to reach these goals [3]. Based on this, a larger interdisciplinary action research project in a municipality in the middle of Sweden was launched. Older persons, their next of kin, staff, and politicians, all of whom are involved in care, participated in the project. The objective was to frame and implement core values and local guarantees of dignity based on participants’ experiences and knowledge of how a meaningful daily life for older persons can be developed [4]. In this study, we focused on nurse assistants’ perspective about a meaningful daily life for older persons in nursing homes.

BACKGROUND

Nurse aides, certified nurse assistants, and nurse assistants (hereafter called NAs) are closest to older persons and provide most of the direct care [5-7] in nursing homes. In the literature it is outlined that NAs ensure that older persons are comfortable, assisting and/or helping with daily activities such as personal care, hygiene, dressing, and feeding. NAs also observe older persons’ response to care and monitor vital signs such as blood pressure [8] and prevent pressure ulcers [9], for example. They also interpret care situations [5], where they have an important role in reporting to other professionals and assessing older persons’ health conditions [7, 8]. NAs also strive to establish relationships [10, 11]. Schirms et al. study [7] revealed that NAs described the care they provide as more than a job: they are driven by a desire to do the right thing. It is the “right” attitude that is required to work with older persons in nursing homes [6, 7] that determines the content and quality of the care [7, 10]. Further-more, it has also been shown that nursing staff use their involvement, friendliness and sensitivity in nursing homes to create positive situations, where the older person is treated as an individual [11].

Alongside NAs there is also the need for an interdisciplinary team of care providers who attend to the older persons’ psychosocial, emotional, spiritual, physical, and clinical care needs [12]. Blomberg et al.’s [6] study showed that the team can design this care and they can initiate changes in the care. A well-functioning team is crucial to good quality of care [13] because the better they work as a team the better everyone feels, including the older persons [7]. NAs have an important role in the team, as they act as the others team members’ eyes and ears [7]. Within the team registered nurses (RNs) promote teamwork with NAs, guiding them in problem solving and decision-making [7, 12]. Occupational therapists also have an important role in the team, as they address different aspects of daily living, and provide advice and support to maintain or increase independence in the older person’s daily activities [14].

There are challenges for staff working in the care of older persons, as there are numerous demands on personnel’s skills [3], and there may be reasons to question the extent to which professional knowledge guides care [5]. NAs working closest to older persons often have little formal training, along with theoretical knowledge, in relation to managers and RNs [5, 15]. However, NAs can use experience-based knowledge consisting of mental models to create care actions [5, 10]. When staff’s actions and decisions are based on their own models instead of theoretical knowledge they may misinterpret the situation, which may lead to inappropriate care [5, 10]. Another perspective emerged in Shin’s [16] study in which the relationship between NAs’ hours per residents and the quality of life of residents in nursing homes was examined: more RNs in relation to fewer NAs meant that meaningful activity and relationship decreased, while more NAs in relation to fewer RNs gave older persons more dignity, autonomy and spiritual well-being. Pfefferle and Weinberg’s [17] study detailed how NAs experienced a devaluation of both themselves and their work through explicit and tacit messages from managers and RNs. NAs’ perspective on their work and their importance are important determinants of the quality of care [7, 11, 17].

Elderly in need of health care and social services should have their daily life arranged as meaningful as possible by staff [3]. Therefore, it is essential to describe how a meaningful daily life might be developed. Since NAs work closely with older persons it is important to look at their perspective and learn how a meaningful daily life can be developed to ensure a well-functioning team. The aim, therefore, was to learn from NAs’ experiences and knowledge about how to develop a meaningful daily life for older persons in nursing homes and the meaning NAs ascribe to their work.

METHODS

Methodologically this project is based on Participatory and Appreciative Action and Reflection (PAAR). What distinguishes PAAR from other action research is the appreciative intelligence [18], which is about taking advantage of people’s ability to be innovative and creative, because if one only sees an organisation’s problems then negativity will persist in the workplace. However, the intention of appreciative intelligence is also to adopt a creative critical approach and seek solutions with the participants [18].

Context and Sampling

In the larger interdisciplinary action research project, six nursing homes and six home care units were randomly selected from a complete list of nursing homes and home care units in the municipality: two that received good reviews, two that received moderately good reviews, and two that received less favourable reviews from a completed user survey [4, 19]. The sampling was guided to cover and reflect different perspectives and experiences [20]. On the other hand, experiences and knowledge can be situated, in other words meaning can exist within the ongoing activity thus becoming the situation itself [21]. Since home care and nursing homes can have different ongoing activities and situations, we studied these two contexts separately. This study focused only on nursing homes. Five nursing homes agreed to participate in the project.

In ordinary workplace meetings we asked the NAs to participate in the study, orally and written, and whether a researcher could follow them and participate in their work to learn from their experience and knowledge of how to develop a meaningful daily life for older persons. All NAs within the five nursing homes who were willing to participate were included. Altogether, 27 NAs between the ages of 24-60 participated.

Ethical Consideration

A number of ethical deliberations and decisions were made to access those in the field in order to learn about NAs’ practices and gain permission in order to work with them and remain [22] in the PAAR project. When the presumptive participants were invited and informed, we were careful to provide information that clearly explained that we were there to learn from them, since they might have seen their work as being questioned. This was done to engage the participants and open up for collaboration [23]. Ethics approval was obtained for the project (dnr 2011/009).

Collaboration and Reflection with Participating Stakeholders

In PAAR, the researcher must be sensitive to what others are feeling, saying and doing, and consider the participants as knowledgeable and capable of participating in the research [18]. Therefore, the focus was to proceed from the participants’ experience and knowledge of how to develop a meaningful daily life for older persons.

Reflective conversations in dialogue form were conducted, which can be likened to open qualitative interviews [24] with the NAs (n=27) within the included five units. The researchers (n=4) also participated in NAs’ everyday work (174 hours), where they also had reflective informal conversations and performed the same care activities to some extent, for example providing personal care and assisting at mealtimes. We had a joint focus on what, how and why different care activities were carried out.

The reflective informal conversations, interviews and participation in NAs’ work were repeated two to three times to build a trusting relationship and gain deeper experience and knowledge. Positive issues for reflection were raised with regard to what factors might be positive in daily life at the time. Questions were asked such as: How are these potential positives achieved? What factors are less favourable, and what obstacles may be found in daily life? Do you have any suggestions as to how these obstacles can be avoided or resolved? To develop a meaningful daily life, what needs to be changed and how and by whom? During the conversations, researchers and participants reflected on and tried various ways of understanding in order to clarify and formulate the experience and knowledge of the participants.

Analysis

The analysis process was conducted in two phases. Firstly, the interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional secretary. The reflective informal conversations, and the researchers and participants’ joint analysis of the situations, were conducted using field notes, which were documented chronologically and compiled on an ongoing basis. Furthermore, interviews and compilations were taken back to the NAs who provided their analysis and reflections on the content where edits and modifications could be made.

Secondly, we used a thematic inductive analysis [25] since data were comprehensive and detailed. In the first step of the second phase, the first author read and reread the data, interviews, informal conversations, and field notes in relation to the research question. In the second step, initial codes was created that identified features in the dataset, it was collated whether it was relevant to each code and marked out. In the third step, the first author collated codes into potential themes, forming sub-themes and main themes. Codes that were left out of the dataset formed a theme called “wait and see”, where few could be added to themes and others rejected. Because a theme does not need to include all of the data it can appear in a relatively small dataset [25]. This step required an interpretation, where the authors (IJ, KB) analysed the relationship between codes, themes and different levels of themes. In the fourth step, we checked if the themes worked in relation to the coded extracts and to the whole dataset, wherein the latter meant validation. In step five, all of the authors defined and refined the characteristic of each theme, where the themes should describe the meaning within the whole dataset. To achieve credibility we tried different names for the themes and worked to describe each theme clearly so it captured the essence of each. This step involved deliberation among the authors where we discuss until we reached consensus. In the sixth step, we chose convincing extract examples where a final analysis was done with feedback to the research aim. Finally, we produced the report of the analysis [25].

RESULT

NAs’ experiences and knowledge about how they can develop a meaningful daily life for older persons and the meaning they ascribe to their work constitute five main themes with sub-themes (see Table 1). The result includes a detailed description of the characteristic of each theme together with extracted examples.

NAs’ experiences and knowledge about how they can develop a meaningful daily life for older persons and the meaning they ascribe to their work.

| Main Themes | 1. To Sense and Find the "Right" Way of Being | 2. To Sense and Read the Older Person | 3. To Adapt to the Older Person | 4. To Share the Daily Life | 5. To have Emotional Involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-themes | To find and adapt the way of being | To read how someone feels | To adapt to the older person's own choices | To have joy with others | To create a meaning |

| Sub-themes | To use oneself as a creator of rhythm | To have an initial picture | To adapt daily life to the older person's body | To have a conversation thread | To be close |

| Sub-themes | To change the way of being | To be the older persons extended arm | To do something together |

To Sense and Find the “Right” Way of Being

To Find and Adapt the Way of Being

From NAs’ experiences and knowledge for how to develop a meaningful daily life it was important that they could sense the older person’s way of being, and discover what state of mind the person was in. This allows NAs to find and adapt to the older persons way of being and respond to every person in the way that suits them individually. In order to adapt it was important, for example, to first knock on the door before entering into the individual’s room and to remain focused in a situation. To have knowledge of the person’s life story could also make it easier for NAs to find and adjust their way of being:

“I change my personality depending on which of the rooms I go in, and I listen differently and I have different kinds of questions because you sense the situation and the person.”

To Use Oneself as a Creator of Rhythm

The NAs stressed that adopting rhythm in their work could create a peaceful and meaningful atmosphere. The NAs chatted with the older person while they worked. They could talk about everyday things or about what they would do in the next moment, for example that they would help the older person turn in their bed. They explained that it was a way to prepare the individual, creating participation, giving them the opportunity to remain focused. Adopting a rhythm in their work meant that the NAs understood which care actions were to be performed and in what order. The NAs felt that this rhythmic pattern provided a sense of peace and security for both the older person and the NAs:

“But it gives a sense of security; I believe that it just floats on. That we know, we do not need to say much [to each other] and we can calm [the older persons] down sometimes when they are a little upset.”

NAs could also use gentle movements and be still to show the older person that they were not stressed:

“You cannot snatch and tear. Be soft, give them time; we do not have to hurry.”

Furthermore, NAs had experiences and knowledge about stepping back and allowing older persons to maintain their independence. They also used the body to create equality, wherein NAs could lower themselves or squat instead of standing over the person. NAs also used their voices to create equality and spoke with the older person as any other person might. When appropriate, humour was used to lighten the mood. Thus, every day became more enjoyable for both the older person and NAs.

To Change the Way of Being

The NAs explained that it was important to break the older person’s state of mind by breaking the individual’s way of being. For example, if the older person was angry or worried the NAs had to try different ways of being that were best suited to the specific situation. If the wrong way of being was used it could stress the older person and led to experiences that could be related to a decreasing meaningful daily life.

“Sometimes NN understands [the older person] and sometimes not, and then NN gets worked up ... and does not take onboard what you say. .... You get to try things out.”

To Sense and Read the Older Person

To Read how Someone Feels

In addition to sensing and finding the right way of being the NAs explained that it was important to sense and read the person in each encounter. This was necessary in order to try to judge how the older person feels. Therefore, feeling well was important in order to sense a meaningful daily life. The NAs explained that to read someone was to interpret signals through body language and facial expressions, and listen to the tone of their voice. They looked for paleness or maybe the individual has eaten less than before, they listened to how someone was breathing, and they could feel if someone was warm or smell if someone had a urinary infection.

However, it was not enough for the NAs to rely on observations — it was also important to ask how someone was feeling and listen to how the answers were given, for instance judge whether the older person heard poorly, had cognitive impairment or if there was another reason for an unclear answer:

“Then I just had to ask a lot too; it’s not screws we work with its people.”

To Have an Initial Picture

The NAs explained that getting to know the older person and their habits and routines were important, as it formed an initial picture that was used to read and compare against the current picture of the individual and judge their health. If the habits and routines changed the NAs could see if the person’s health was better or worse. This could be the case if someone was more tired or had started to drink more than before. In this regard the NAs’ knowledge of the person’s habits and routines could help them identify if the person had an onset of diabetes, for example. Being able to read the older person was especially important if the individual could not communicate verbally. The NAs expressed how they read the person’s body language and sounds to get an idea of how the person felt:

“It is seen in the face … if [the older person] … picks the napkin … rocks back and forth or moves faster, screaming.”

To Adapt to the Older Person

To Adapt to the Older Person’s Own Choices

From the NAs’ experiences and knowledge it was also important for older persons to make their own choices for how a meaningful daily life should be developed. This could mean that they could choose when they wanted to go to bed at night or get up in the morning, and the NAs had to adapt:

“And some people would of course lie in bed as NN [the older person], she wanted to come up for lunch today so then she got to do it.”

NAs explained that some older persons found it difficult to make their own choices; therefore, NAs offered different options that were easier to choose from, allowing the older person to feel involved.

To Adapt Daily Life to the Older Person’s Body

NAs emphasised that daily life needed to be adapted to the older person’s body — strength and energy — to make their daily life meaningful. It could be difficult to stay awake for long periods, so the older person needed to rest and lay down for a couple of hours during the day to gather strength:

“The residents who live here now need a break after the food or perhaps after they’ve been up for a few hours. Their bodies need it.”

NAs had experiences and knowledge about not always adapting to the older person’s choices because it could endanger their health. For example, an older person might choose to not want to get out of bed; however, getting out of bed and moving around helps ensure their body maintains its health.

To be the Older Person’s Extended Arm

From the NAs experiences it was crucial that care actions were based on the person’s habits and routines, and not to the routines of the nursing home, because it could be insult ing for the older person to not get what they were used to, and it was reassuring to keep habits and routines:

“It’s very meaningful to have their routines that prevent the older persons becoming anxious.”

The NAs described how they had to know which beverage the older person wanted. Furthermore, it was important how the breakfast was prepared, for example an egg should be boiled exactly how the older person preferred. That the NAs sought to be the older person’s extended arm was evident in a participating observation:

“A NA keeping on for a long time and prepares gruel. She stirs it in the cup and opens the microwave. Runs the microwave, takes it out and stirs, running and opening the microwave, takes it out and places it on the bench, takes the spoon and runs it down and around and around.”

A meaningful daily life could be developed if the actions the older person could no longer perform would be carried out by NAs in exactly the same way as the older persons themselves had performed them. The NAs gave instructions to the participating observer and explained extremely thoroughly how the bed was made and how compression socks were put on and how the cleaning was performed.

The NAs emphasised how clean it was in the older person’s home, which was linked to dignity and how they were regarded as a person. If it was untidy and dirty, it could be perceived that the older persons identity was also untidy and dirty. On the other hand, if the person did not want to clean as often the NAs did not do this.

Every detail would be consistent as if the person would have performed the actions themselves, as it was related to their way of being:

“It is important with the small details how anyone wants it. It can be insulting if someone does not get it as you want it. If you do not do it right the day begins bad for the older persons.”

To Share the Daily Life

To have Joy with Others

The NAs outlined that the older persons in the nursing home could be happy with one another. There were those who were seen sitting down in the living room close to others with the front of their bodies against each other and talking with their heads against each other. Sometimes the NAs needed to start conversations and facilitate the contact between the older persons for it to be meaningful.

To have a Conversation Thread

The NAs understood that the older persons were interested in the NAs’ daily life outside the nursing home. They wanted to know what they did in their spare time, how a course or a party was. Yet, the NAs were also interested in the older persons’ daily life. NAs and the older persons also continued conversations they had begun earlier:

“It’s so fun to talk to NN; it is hard to tear oneself away.”

Conversations also became important for the NAs, helping make their daily lives meaningful.

To do Something Together

For developing a meaningful daily life the NAs explained that it is vital to do something with the older person such as playing bingo, gymnastics, solving crosswords, watching a movie, or taking a walk. The NAs felt that doing activities with the older persons also gives meaning to their daily life:

“It makes me happy when people are happy ... when we do something together and you see that the person will be happy and satisfied then I also feel happy.”

From the NAs’ point of view it gave meaning to daily life for the older person to plan for a party or an excursion. It was not the event itself that was the best, but that they shared something and had something to look forward to and talk about afterwards. This was shown clearly in a participant observation:

In a nursing home NAs and the older persons planned to watch the English wedding that would be shown on television. They planned what they would eat, and that they would sit at long tables. The planning was also about what clothes to wear. After the wedding the NAs described how the most enduring of the older persons sat there all day long and ate strawberries, lemon cake and drank cider. Afterwards the NAs and the older persons talked about what they had seen on TV. They wondered if Princess Victoria was pregnant. They also wondered why the Swedish queen and king were not invited to the party after the wedding.

The NAs explain that sometimes it was the little things that allowed for interruption and had a meaning for the older persons, for example painting nails or reading the day’s horoscopes. The NAs read everyone’s horoscope at the breakfast table, which in turn resulted in many laughs. It also gave a meaningful daily life by celebrating the usual weekends and the traditional feasts.

There were also situations when the NAs had to perform duties that the older person could be involved with, help or just to sit next to and listen to the NAs or engage in conversation:

“You can bring [an older person] to the laundry room. Now we will wash.”

To have Emotional Involvement

To Create a Meaning

The NAs stressed that the emotional involvement they have for their work and the older persons gave them meaning in their work and a meaningful daily life for themselves and the older persons. They expressed it as being “wholeheartedly” involved in the older person’s life and the work and giving of oneself. This was also a way to be professional:

“There is a need of extra driving involvement to work with older persons. You need a burning passion and interest in your work.”

For developing a meaningful daily life it was important that the NAs liked both the older persons and work such as cleaning and washing.

To be close

It was obvious in the observations that the NAs knew the older persons and liked them. This was expressed in their body language when they were close, hugged the older persons or gave them a caress on the cheek. The NAs also received hugs from the older persons. One of the NAs explained that closeness was natural when you like and knew each other:

“Give a hug or receive a caress on the cheek. Sometimes it may be that the hand has been somewhere else before it falls on my cheek. But that’s on me; I can wash the cheek afterwards. You know them so well that you like them.”

DISCUSSION

In this study, we learned from NAs’ experiences and knowledge of how a meaningful daily life can be developed for older persons in a nursing home. For a well-functioning team [6, 12, 13] it is crucial to learn from NAs and use that knowledge in the care of older persons, that is to sense and find the right way of being, and read the older person to judge how the person is feeling. It is crucial to adapt to the older person and share their daily life. The NAs’ emotional involvement is needed to create meaning in their work and a meaningful daily life for older persons. As it was earlier described that NAs use knowledge based on experience and mental models [5, 10]. It is useful to further discuss the results theoretically and attempt to link them to different forms of knowledge NAs might use in developing a meaningful daily life for older persons. The results will be discussed with the help of Aristotle’s three forms of knowledge [26]: phronesis, which represents practical wisdom; techne, which refers to practical knowledge; and episteme, which represents theoretical knowledge [27].

To Sense and Find the “Right” Way of Being

It was clear from the NAs that to develop a meaningful daily life it is important to sense the older person and find the right way of being that was appropriate for each individual. This is consistent with a previous study with older persons in nursing homes, wherein they explained that they felt secure and at home due to the staff’s encounters with them and that this creates a meaningful daily life [28].

In Wadensten [11] et al. study, a positive encounter was described as being present, listening, and showing involvement and treating the older person as an equal. This is in line with this study’s results, wherein NAs used themselves and their bodies to create the right way of being, conveying peace, security, equality, and independence. NAs sensing and finding the “right” way of being, where they create rhythm, can be linked to Gadamer’s concept of “tact” [27]. One can sense where another person is in a certain situation, ultimately adapting to another person’s tact and avoiding coming too close and threatening that person’s integrity [27 p. 15]. This constitutes an example of practical wisdom, which is phronesis [26, 27], and can be described as experienced know-how, an embodied knowledge [29] that NAs used when caring for an older person.

To Sense and Read the Older Person

NAs found it important to read how the older person felt, using their senses to judge how the person was feeling. However, it was not enough to just read the person and assess their condition: posing questions was also essential. The importance of questions also raises Mellor et al. [30] study, which outlined that if staff solely based their assessment on observation some symptoms such as depression may be difficult to discover. Older persons may experience health and positive well-being despite their health problems, but those problems must be alleviated and managed [31]. Consequently, NAs’ observations of and questions posed to older persons remain important [7]. In this study, when NAs read the older person and judged that the person had diabetes (as well as other studies that monitored and observed vital signs such as blood pressure [8]), it is referred to a knowledge that is obtained through observations and understandings that can be linked to a theoretical knowledge. This is a knowledge that is learned through training [27, 32].

To Adapt to the Older Person

The NAs expressed that it was crucial to adapt everyday life to the older person’s habits and routines in order to develop a meaningful daily life, rather than to the routines of the nursing home. This is in line with older persons’ preferences to keep their habits and routines in nursing homes to help ensure a meaningful daily life [28]. Their identity can be threatened when health deteriorates and they can no longer maintain habits and routines [33]. Our routines and habits namely represent our lifestyle and self-identity [34]. The NAs stated that how the care actions were performed was important, as they were connected to the older persons’ habits and routines, in other words their identity. This represents the practical knowledge, techne, which can be described as practical productive skills based on routines [27, 32]. Techne is practical knowledge and can be described as craftsmanship, where the craftsman learns by experience how the actions should be performed [27].

It could be that the older person’s own choices were not possible to adapt to, as they were a danger to their health. For the NAs there is a distinction between body and soul when the older person must get out of the bed. The body’s physical needs take precedence over one’s choices, as their health can be affected in the long term if they do not get out of bed and physically move around. Based on this the NAs did what was best in the situation the older person was in. This can be interpreted that NAs used a practical wisdom [27, 32].

To Share the Daily Life

The NAs and the older persons in the nursing home participated in activities together such as playing games, watching movies or baking. Many nursing homes organise group activities. This might suggest, as Tuckett [35] describes, homogenised activities with mandatory participation, which may represent an institution’s thinking. The NAs also shared what was just a disruption of everyday life, a meal, painting nails or a conversation thread. They also had an interruption to look forward to (the English wedding) that also gave them something to talk about afterwards, which all together develops a meaningful daily life. This is in line with a study by Hjaltadóttir and Gústafsdóttir [36] that explains that activities can be seen as interruption in a monotonous daily life. From an older person’s perspective these activities give energy [28]. Being active and socialising can provide feelings of pleasure and a sense of belonging [37]. The activities and the interruption can be described as sharing something together, which allows for meaning in both the older persons and the NAs’ daily lives.

The results are in line with Westin and Danielsson’s [38] study, wherein encounters with staff were described as encounters with old friends, and relationships between the older persons and the staff were characterised by community and sharing different life experiences. In interviews with older persons, it is precisely the community and the relationship with the staff that creates a meaningful daily life [28]. This sharing of something and the community can be seen as a “play”, something that happens by itself with no obligation [27]. It is also in this play that both the older persons and the NAs forget about themselves for a moment. This can be described as doing what is best for the older person so that they can have meaningful daily lives, which constitute a practical wisdom [27, 32].

To have Emotional Involvement

In this study, it was the NAs’ emotional involvement in the older person’s life and in their work that gave them a sense of meaning. The NAs liked the older persons and there was a natural closeness. In a previous study, older persons found affection and reciprocity between themselves and the NAs important for a meaningful daily life [28]. For NAs it was about being wholeheartedly engaged in their work and giving of oneself. It was the emotional involvement that led them and was the driving force in their work. Thus, it was more than a job [7] and it determined the content and quality of the care [7, 10]. NAs’ use of emotional involvement is supported by Benner [39], who emphasises that to understand the older person’s situation emotions must be used, because it is emotions that teaches us how to act in practice [40]. The rational and emotional are intertwined, as it is our emotions that form judgement, make decisions and act [40]. Emotional involvement can be described as emotional intelligence or as an embodied way of knowing [39], where the care action is transformed into an art [29] (see Fig. 1).

NAs developed a meaningful daily life by sensing the older person’s and finding the “right” way of being which can be linked to practicalwisdom (Theme 1). They sense and read the older person in order to judge how the person is feeling that can be understood as theoretical knowledge (Theme 2). They adapt to the older person which can bee seen as practical knowledge (Theme 3) and share their daily life which could be described as practical wisdom (Theme 4). NAs use emotional involvement to develop a meaningful daily life for the older person and meaning in their work and thereby making each other’s daily lives meaningful viewed as an embodied way of knowing (Theme 5).

Methodological Consideration

For the researchers there were several difficulties with regard to learning about NAs’ experiences and knowledge. One difficulty in the PAAR project might be the researchers’ pre-understanding since it could mislead the analysis of how to develop a meaningful daily life. However, it was emphasised that the researchers should clarify their pre-understanding and write it down at the start of the project, which could make it easier to manage [41]. Another difficulty was creating field notes that were sufficiently detailed in connection with the participation observations. If the observations had been videotaped then more of the complexity of practices within the NAs’ work would have been caught [42]. On the other hand, videotaping might affect the interaction between the participating observer and NAs. Therefore, NAs may guard their words and actions, which will make it difficult to learn from them. One way to learn from the NAs was through participating observations and in the reflective conversations with a joint focus on what, how and why different care activities were carried out to develop a meaningful daily life for the older persons.

CONCLUSION

We learned from the NAs’ experiences and knowledge that developing a meaningful daily life in a nursing home requires emotional involvement, which was the driving force in their work and viewed as an embodied way of knowing. It was also the force behind sensing older persons and finding the “right” way of being, which can be linked to practical wisdom. The NAs’ emotional involvement helped them sense and read the older person in order to judge how the person is feeling, that can be understood as theoretical knowledge. Emotional involvement was also what drove how care actions were performed, which are crucial and should be adapted to older persons, and which can bee seen as practical knowledge. The NAs shared the older persons’ daily lives which could be described as practical wisdom. Based on the results we can conclude that NAs use emotional involvement to develop a meaningful daily life for the older person and meaning in their work and thereby making each other’s daily lives meaningful. Since the rational and emotional are intertwined, the NAs’ way of developing a meaningful daily life can be linked to three forms of intertwined knowledge: theoretical knowledge, practical knowledge and practical wisdom. These results could be used within the team, ultimately helping constitute a meaningful daily life for older persons in nursing homes.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design: IJ, AK, KB. Data collection IJ, CF, CW and analysis: IJ, CF, CW, AK, KB, Manuscript preparation: IJ, CF, CW, AK, KB.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for the participation of the NAs. This study was supported by grants from Örebro University Sweden.