All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Evaluation of Staff’s Job Satisfaction in the Spinal Cord Unit in Italy

Abstract

In July 2007 a Spinal Cord Unit was set up in Turin (Italy) within the newly integrated structure of the Orthopaedic Traumatologic Centre, warranting a multidisciplinary and professional approach according to International Guidelines. This approach will be possible through experimentation of a personalized care model. To analyze job satisfaction of health care professionals operating within the Spinal Cord Unit, preliminary to organizational change. Data collection was carried out by using questionnaires, interviews, shadowing. Results from quantitative analysis on the self-filled questionnaires were integrated with results from qualitative analysis. All the health care professionals operating in the field were involved. Positive aspects were the perception of carrying out a useful job, the feeling of personal fulfilment and the wish to engage new energies and resources. Problematic aspects included role conflict among staff categories and communication with managers. The positive aspects can be exploited to create professional practices facilitating role and expertise integration, information spreading and staff identification within the organization rather than team work. Data of job satisfaction and self efficacy of health care workers can be considered basic requirement before implementing an organizational change. The main challenges is multiprofessional collaboration.

INTRODUCTION

Since 1988, the Functional Rehabilitation Center (FRC) of the Orthopedic Traumatology Center (OTC), Turin has been caring for people with spinal cord injury (SCI) in the sub-acute or chronic clinical stage. In July 2007, the Spinal Cord Unit (SCU) operating within the FRC was transferred to a new facility. With this move, total bed capacity was expanded from 25 to 46 beds in two wards where patients with SCI receive care from the acute stage to discharge home after having completed a rehabilitation program.

The new issues related to the management of the SCU brought up the need to revise and improve service organization. Therefore, the project “Experimentation and evaluation of a personalized health care programme for spinal cord injury patients in the Turin SCU” was launched, funded by the Piedmont Region within the 2006 Healthcare Research Plan. The aim of the project was to identify the strengths of the previous model from which new organizational methods and tools could be developed and presented on a three-day training course for the health care professionals (physicians, nurses, rehabilitation and support staff) working at the SCU. The present study is one component of the initial phase of this action-research project which uses context analysis to identify strengths and weaknesses, to propose solutions and to implement changes by assessing processes and outcomes. The survey was conducted between January and April 2007.

The aim of this study is to assess job satisfaction of FRC personnel, using organizational well-being and discomfort indicators. In particular, we aim to investigate whether individuals working within the FRC setting are able to express their potential through effective relationships. Furthermore, we want to highlight weak areas which represent a reason for distress, poor staff motivation and sense of belonging. Results will be used to plan new SCU organizational models.

Job satisfaction in medical teams has been carried out extensively with most studies focusing on nurses. Correct evaluation of job satisfaction became fundamental for any organization as shown by Faragher [1] in their meta-analysis, for improving employees’ physical and mental well-being. Job satisfaction was much more strongly associated with mental/psychosocial problems, than with physical complaints like cardiovascular disease and musculoskeletal disorders. The authors discussed whether or not organizations should develop stress management policies, including counselling services, helping to identify job dissatisfaction and getting employees to find solutions. According to Mc Neese-Smith [2] nurse satisfaction derives mainly from patient care, balanced workload, relationships with co-workers, salary, professionalism and nurses’ cultural background. The Finnish study by Makinen et al. [3] examines the relationship between methods of organizing nursing and employee satisfaction and shows that the strongest contruibutor to nurses’satisfaction with supervision was mainly the opportunity to write patients’ nursing notes, patient-focused work allocation and accountability for patient care. A significant relationship between organizational structure variables and job satisfaction for nurses in Illinois (USA) was shown [4]. The study suggested that work environments in which individuals were involved with peers in decision-making and task definition were positively related to job satisfaction. A significant relationship was found between job satisfaction and the organizational structure dimension of vertical participation and horizontal decision making. Accordingly, Zangaro-Soeken [5] meta-analysis of 31 studies examined the strengths of the relationship between job satisfaction and autonomy, job stress and nurse-physician collaboration among registered nurses working in staff positions. Job satisfaction was most strongly correlated with job stress, followed by nurse-physician collaboration and autonomy.

Research carried out in one of the largest Canadian Regional Health Authority Facilities by Best et al. [6] described nurse satisfaction components and their relationship to patient acuity and staff mix. Autonomy, professional status and organizational policies significatly decreased when patient acuity increased. Alternately, satisfaction with organizational policies and task requirements both increased significantly with higher proportions of RNs to total staff. None of the nurse satisfaction components was significantly correlated with workload index. Numerous comments described direct patient care as the best liked aspect of nursing practice, supported by other comments suggested increased clinical autonomy was valued.

A literature review by Lu et al. [7] also contributed to define the relative importance of the many identified factors to nurse job satisfaction. The factors with very strong relationship are: job stress, organizational commitment, depression, cohesion of the ward nursing team. Authors underlined that more research was required to produce a strong causal model incorporating organizational, professional and personal variables for the development of interventions to improve nurse retention.

Comber & Barribal [8] in the review suggest that stress and leadership issues exert influence on dissatisfaction and turnover for nurses. Level of education achieved and pay were found to be associated with job satisfaction although the results for these factors were not consistent. A literature review by Utriainen & Kyngas [9] suggested that job satisfaction varies in different specialty areas of nursing work. Two significant themes in that field are interpersonal relationship between nurses and patient care and different ways of organizing work.

Witting et al. [10] examined variables that contribute to work satisfaction among rehabilitation professionals involved in brain injury rehabilitation and suggest that work satisfaction might be maximized through two principle domains: training and organizational support.

The findings of the literature have indicated the importance of a positive work environment with reduced stress and increased job satisfaction. Conversely, most of the studies have demonstrated the negative influence that increased stress can have on job satisfaction, retention, and group cohesion.

This paper addresses the question:

- What is the level of job satisfaction of staff employed in the Functional Rehabilitation Center?

- Is there a significant relationship between job satisfaction and professional practice environment, organizational characteristics and organizational models?

MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

Different methods has been used to have a more complete vision of job satisfaction of staff employed in the professional practice environment [11].

Methods selected for the organizational context analysis are reported chronologically.

- Multidimensional Organizational Health Questionnaire (MOHQ) experimented and validated on a champion of 18.000 subjects in Italy [12]

During validation the model of the relationships among variables has been examined with the technique of analysis of the models of structural equations implemented through the program EQS [13]

The questionnaire is composed of 109 affirmations related to behaviours and observable conditions in the environment of job, each of which is referred to one of the health dimensions or indicators.

The questionnaire, which monitored job satisfaction in the public sector staff, included the following nine areas (personal data, comfort, ten well-being dimensions, safety, job features, positive and negative organizational well-being indicators, psychophysical well-being, readiness to innovation and suggestions) gathering information by using a four-point Likert scale from a minimum of “never” (score 1) to a maximum of “often” (score 4) or unsatisfactory (score 1) to a maximum of “good” (score 4).

Questionnaires were given to all staff members (77) on the two FRC wards and were filled in independently.

Data analysis was carried out using software specifically designed for the questionnaire [12].

The program allows the measurement of the distributions of the indicators of each dimension of the concept of "organizational well-being" and draw tables and graphs. Both single item absolute scores and item scores relative to the total mean, allowed to confirm elements of strength as well as aspects requiring improvement, in all the areas examined. Designer scores were deemed as positive when equal or over 2.9; fairly good when ranging between 2.6 and 2.9; critical when below 2.6.

The total mean score obtained by an institution, appeared to be the best starting point to evaluate the organizational well-being in that specific set, since it was not an arbitrary absolute value but rather an element which allowed to consider the points brought about by that group of employees. - Face-to-face interviews were conducted on a propositive sample composed by all staff coordinators (n.7), the professional support workers who collaborated with the bed services (1 psychologist and 1 social worker), and a convenient sample of nurses (n.6), physiotherapists (n.3) and health care assistants (HCAs) (n.2). During interviews participants were asked to express an opinion about their professional experience at the centre. Interviews (lasting about half an hour) were carried out with a format allowing people to express themselves freely, in order to give the most authentic picture of themselves and their reality.

- Shadowing [14], a technique used to observe social interactions, was carried out by L.C. on one of the two (FRC) wards from 7 am to 12 pm for twice a week (Monday and Wednesday), during morning hygiene care and preparation for physiotherapy, with the aim to identify critical aspects as regards specific day-time routines.

The research methods are described in Table 1.

Description of Research Methods

| Methodology | Description | Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire anonymous | It’s composed of 109 affirmations. Time needed to fill the questionnaire: 15 minutes. All information deriving from questionnaires will be anonymous. | Completed by all team members (doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, nurses aids, psychologist, social worker) |

| Spontaneous interview | Special conversation where participants are engaged in a verbal interaction to reach a pre-defined cognitive goal. | Addressed to Coordinator, psychologist, social worker as opinion leaders in the context |

| Shadowing | Technique used to observe social interactions. The researcher had followed as a shade the observe. It consisted in a description as faithfully and complete as possible of the characteristics of the event, behavior or situation and of the conditions in which take place. | With a sample of randomly selected nurse |

The hospital review boards and the unit coordinators were informed about the study content and they approve the study. The study participants were informed about the study purpose, the interview process and the need for audio-taping. They were informed that participation was voluntary and confidentiality assured. All participants gave their verbal consent.

RESULTS

Results from quantitative analysis on the self-filled questionnaires were integrated with results from qualitative analysis taken from interviews, external observations and nurse shadowing in order to permit a more significant interpretation of data.

Details of the 58/77 (76 %) questionnaires filled out and returned were as follows: 4/9 (45%) by medical staff; 7/13 (54%) by physiotherapists; 24/30 (84%) by nurses; 13/15 (87%) by HCAs; 9/10 (90%) by surgery/day hospital (DH) staff (nurses and health care assistants).

Furthermore, 15 interviews, 5 external observations and 1 nurse shadowing.

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 2. Good representativeness of all professional categories operating at the CRF was observed.

Description of the Staff Sample that Filled in the Questionnaire

| Gender | ||

| N | % | |

| Male | 12 | 20.6 |

| Female | 45 | 77.5 |

| Undeclared | 1 | 1.9 |

| Total | 58 | 100% |

| Age | ||

| N | % | |

| Up to 34 years | 11 | 18.9 |

| Between 35 and 44 years | 24 | 41.4 |

| Between 45 and 54 year | 18 | 31.1 |

| Over 54 years | 2 | 3.4 |

| Undeclared | 3 | 5.2 |

| Total | 58 | 100% |

| Employment Pattern | ||

| N | % | |

| Full-time | 49 | 84.4 |

| Part-time | 9 | 15.6 |

| Total | 58 | 100% |

| Staff Category | ||

| N | % | |

| Physicians | 4 | 6.9 |

| Nurses | 24 | 41.3 |

| Physiotherapists | 7 | 12.0 |

| HCA | 13 | 22.4 |

| DH/professional workers | 9 | 15.5 |

| Undeclared | 1 | 1.9 |

| Total | 58 | 100% |

| Years of Work at the CRF | ||

| N | % | |

| Less then 5 years | 12 | 20.6 |

| Between 15 and 24 years | 36 | 62.1 |

| Over 25 years | 6 | 10.4 |

| Undeclared | 4 | 6.9 |

| Total | 58 | 100% |

On a four-point Likert scale a total mean score of 2.83 was obtained from questionnaires, deemed as fairly good. Among the positive aspects, willingness to go to work and satisfaction about relationships in general emerged; both items scoring a mean of 3.2 (positive). The possibility offered by the centre to acquire new technologies was also seen as a good opportunity to improve personal performances. Job was perceived as useful with a mean score of 3.1. Capacity to welcome patients’ requests, wish to engage new energies at work (except for physicians) and feeling of personal fulfilment were all considered positive signs.

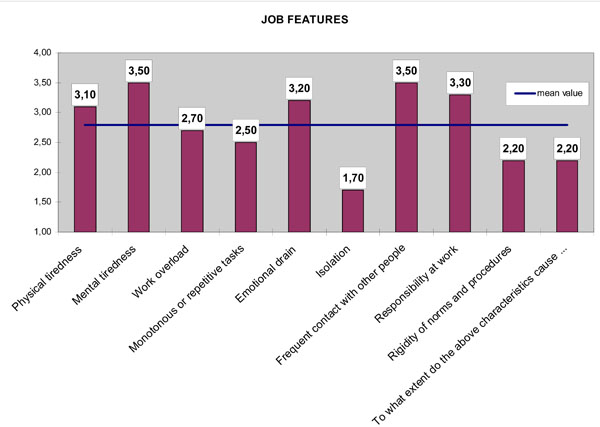

As regards job features, work was described as very demanding, both physically (except for physicians) and mentally. Moreover, both emotional overload (except for DH/surgery staff) and perception of direct responsibility made every day activities harder (Fig. 1).

Job feature.

Comfort and safety were considered a difficulty in order to operate freely in everyday routine situations. Indeed, mean scores of 2.5 and 2.4 for comfort and safety, respectively, represented a light criticism made significant by its recurrence in the interviews. Most critical items were electrical safety (mean score of 1.8) and adherence to smoking prohibition (mean score of 1.9). From the interviews strong expectations emerged on the centre’s new setting with the hope to effectively reduce environmental related inconveniences. Stress also represented a negative factor, which influenced staff well-being (mean score of 2.1).

Relationships built with patients and among professionals appeared to be crucial. The relationship with patients, among colleagues belonging to the same staff category, with other professionals and with supervisors was carefully analysed.

Relationship with Patients

Patients, including out-patients, often contacted CRF due to lack of support on behalf of community health structures, causing a rather heavier workload. Description of patient categories made in the interviews objectively clarified the feeling of tiredness expressed through the questionnaires in the area regarding task features. In fact, in many cases these patients and those with social problems (in recent years the number of non EU citizens, often with no visa or under legal proceedings has increased), who required long-term hospitalisation (average one year) with possible re-admissions and frequent follow-up appointments often had to turn to the centre. Furthermore, the evolution of primary intervention techniques which allows saving the lives of patients with severe spinal cord injury has led to even more complexities to care approach. Injured patients were, on average, young people and the injury impinged profoundly on their quality of life. They required very profound emotional support as well as qualified clinical care.

Relationship with Colleagues Belonging to the Same Staff Category

What emerged from the questionnaires regarding relationships between colleagues of the same staff category concerning organizational well-being appeared to be controversal. All professional categories reported a positive mean score (over 3.0) except for physiotherapists who showed a critical mean score of 2.6. Aspects which each category consider a priority for improvement can be summarised as follows: physicians underlined the lack of sharing information and perceived both lack of adhesion to institutional requirements and lack of effort in achieving objectives; according to nurses and HCAs there was lack of communication among categories, while physiotherapists underlined the lack of information sharing within the group, failure to solve problems through debates and lack of common effort to reach results.

In particular, interviews indicated strong competition between newly employed physiotherapists and senior physiotherapists: “Senior physiotherapists have no motivation and they just hinge on the group” whereas “New employees have no tools to do their job correctly, therefore, they depend on seniors” (interview n. 7), “Seniors jealously keep information of their experience to themselves as a form of supremacy... they are envious of what juniors, free from family commitments, can accomplish with patients at quieter times (at night, during weekends and holidays...)”. Seniors blame juniors: “... of being arrogant, because of their academic title and of creating clans where no one else is included” (interview n. 10). Staff coordinators declared they were aware of the matter, however, their attitudes went from getting personally involved to describing the situation and simply acknowledging the actual difficulties in finding solutions.

Relationship with Colleagues Among Staff Categories

Lack of time dedicated to multi-disciplinary and multi-professional discussion in order to define the care plan was reported in several interviews. Possible reasons mainly concerning organizational matters were identified: “Adequate times and spaces are missing” (interviews n. 1-6-18). It appeared unfeasible to organise case meetings with all health care professionals, since activities were organised very tightly, leaving no space for staff to meet.

In this context the results of teamwork remained unnoticeable. Every member of staff considered his/her own professional space as independent and fought to defend its borders: “Each one minds his own business” (interview n. 18). Interviews and external observations helped to elucidate specific aspects of the matter.

- Physiotherapists often underlined the importance of their care role: “We are number one” (observation n. 2). They also believed their work to be intrinsically individual, since the relationship they established with patients was exclusive: “Each patient is referred to one physiotherapist only, who takes care of his/her patient throughout rehabilitation”, “Working on our own does not represent a problem for us” (interview n. 14). The only need expressed by physiotherapists was for the physiatrist to be more regularly present in the gym.

- Nurses felt as if they had a minor role. If the gym represented a place for care and hope the ward was seen as the place of suffering and thus making it difficult to acknowledge their efforts. Furthermore, time was included as a source of distress in the relationship with patients: “In the ward activities go on 24 hours a day and not just for a few hours like for therapy” (interview n. 10).

- Physicians often feel deprived of their role (in the questionnaire the mean score for role mix up was 3.2), since other staff categories, physiotherapists in particular, tended to treat them as bureaucrats which they found offensive.

- Professional support workers (psychologist and social worker) often felt involved in this “class struggle”. They listened to them and offered informal counselling, although what emerged from the interviews was the need to appoint external experts in order to provide emotional support to the group.

- The HCAs declared “Everything is fine” (interview n. 19). However, triangulation revealed rather divergent forms of job satisfaction. During the survey these professional workers remained in the shadow, they were never mentioned. Further investigation regarding job perception would be required.

Strong alliances among group members to the point of nearly neglecting patient hygiene and comfort emerged from shadowing. It was observed that nurses had to recruit colleagues and HCAs in order to assist patients assigned to them to speed up and avoid delays before initiation of physiotherapy sessions. In case of workload imbalance, nurses helped each other thus forgetting the global care model which should be carried out by team work. What emerged was a strong polarisation towards physiotherapy against personal care.

Relationship with Managers

Questionnaires revealed fair treatment (mean score 2.8) and good job support (mean score 2.9). Data from positive indicators, however, showed some critical values as regards trust and appreciation. From the interviews some inconsistencies emerged. According to physicians critical points were represented by scarce response to their requests, enforced organizational changes, and general lack of communication. Nurses agreed on the fairness of treatment but they declared lack of involvement and support. They felt under control by managers, in particular when investigated about current difficulties with no certainty of actual intervention. The physiotherapists’ situation appeared most unfavourable. They denounced strong iniquity concerning the evaluation of their work, inconsistent behaviour of supervisors, lack of communication and involvement.

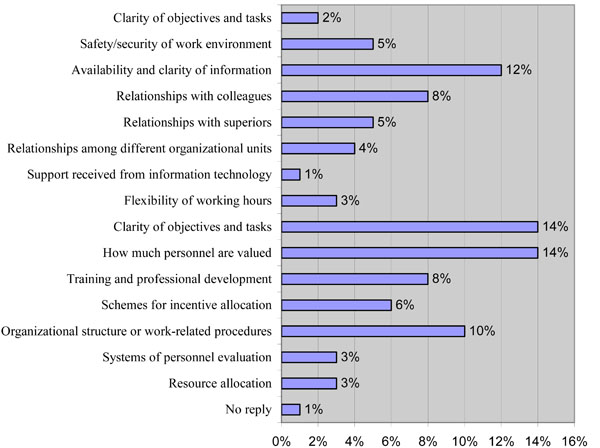

Suggestions reported in questionnaires and summarised in Fig. (2) can represent a starting point for defining priority interventions and at the same time giving value to staff expectation and analytical skills.

Organizational aspects to be urgently improved-suggestions.

DISCUSSION

In consideration of the results presented we discuss that the crucial pre-requisite for any organizational change in the care of spinal cord injured people is the common acknowledgement of roles among all professionals. Nurses enrolled in our study felt the weight of responsibility especially during night shifts and week-ends, when they had to make up for the absence of other staff members. On the other hand, their role became underestimated when all health care professionals were on duty. Extensive research has been carried out to analyse how nurses and physiotherapists perceive their role and how it is perceived by others. Pellatt [15] provided a very accurate description of nurse and patient perceptions of the nursing role in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Nurses saw their role as multifunctional, characterised by the ability to explore, encourage and help patients do what they could not do by themselves anymore. The emotional support offered to patients and their families when in difficulty was also enhanced. Patients described nurses as those coordinating every day care practices, preventing pressure sores, administering drugs and rehabilitating bladder and bowel control. Both nurses and patients underlined the significance of a 24-hour relationship.

Relational dynamics emerging from our data reflected the difficulties, mainly regarding the sense of discomfort denounced by nurses that felt as if they had a minor role. Waters et al. [16] pointed out that therapists (physiotherapists, occupational therapists and speech therapists) considered themselves experts, while nurses considered themselves and were perceived as separate members from rehabilitation, although they played a functional role in this field. Furthermore, the majority of staff interviewed found it difficult to define the nursing profile. Data from literature reviewed by Low [17] confirmed that nurses have an effective role in rehabilitation, but that the boundaries were not clearly defined. In a qualitative investigation Kneafsey et al. [18] underlined that while nurses had an active role in rehabilitation. Their contributions are making assessments, referring to other members of the multi-professional team, advocating for and liasing with other services, halping people to adapt, teaching and motivating patients and carers, supporting and involving families, and proving technical care. They had to face a number of challenges including lack of recognition, lack of time for rehabilitation and paucity of referrals for rehabilitation.

Dalley and Sim [19] investigated nurses’ perceptions of physiotherapists as members of the rehabilitation team. Nurses saw the role of physiotherapists as being only concerned with mobility and movement. Physiotherapy was also perceived as specific, while nursing was perceived as generalised. Physiotherapists were seen as experts who underwent a wider training programme specific for an operational area. In our study a number of aspects overlapping this scenario were evidenced. In particular, nurses showed the same attitude toward physiotherapists, the same mixed up feeling of acceptance and mild frustration, facing the idea that patients would be able to get up and walk thanks to physiotherapists and not nurses. Pellat [20] suggest that patients perceived physiotherapists as the key of rehabilitation.

In our study nurses expressed strong empathy for patients, as a result of spending the entire day in close contact. Physiotherapists were perceived as having insufficient understanding of nurses’ role, seeing ward activities as focused on gym activities and nurses’ role only finalised to the rehabilitation programme. Furthermore, consistency emerged in relation to the exchange of professional skills and information on patients’ conditions. The nurses expressed the need for effective inter-professional working aimed to improve patients’ care, but they did not specify which competencies could be exchanged.

Dalley and Sim [19] underlined the different ways the two health care professionals behaved toward patients, with physiotherapists being more formal and authoritarian, and nurses more informal and able to put themselves on the same level as patients. Physiotherapists and occupational therapists in Suddick et al. [21] reported the effective use of teamwork and interdisciplinary team approach. They underlined the benefits both for team members, as well as for nurses and patients, but they also underlined that team composition and structure was variable among the different working teams. Perception of teamwork was not an issue for the physiotherapists included in our study, who evidenced the relationship with staff coordinators as a difficulty. New graduates are expected to become skilled in a wide range of skills as being self-aware and learning about leading teams, coordinating care, team dynamics, managing conflict, communication and evidence-based practice.

Satisfaction of interdisciplinary rehabilitation team members with case meetings was analysed by Sivaraman Nair and Wade [22], underlying the strong requirement for accurate exchange of information among staff, patients and their families for effective interdisciplinary work. With the perception that their job difficulties were not neglected, staff members allowed a definitely positive picture of their working life to emerge. Locke et al. [23] also described in detail the firm relation between goals and satisfaction, and the role of goals as incentive mediators.

In according to a previous research conducted in the same context [24], the study enabled us to explore the specificities and criticalities in the current FRC rehabilitation model and suggest that organizational aspects to be urgently improved are clarity of objectives and the availability and clarity of information [25]. Specifically in order to improve work quality environments in this setting the aim will be to re-define the team roles within a specific care programme. As implication for resource management, data of job satisfaction and self efficacy of health care workers can be considered basic requirement before implementing an organizational change.

CONCLUSIONS

The level of data reading presented in this paper provides an initial indication. The discomfort indicators described (low levels of motivation, lack of trust, poor team identity, lack of care planning sharing, etc.) reflect a condition of psychological distress, which will require particular attention before proposing organizational changes. The evolutionary process preceding the organizational transformation is still fully open. The team must be able to express the need to cooperate by using positive relational approaches and to negotiate times and modes through scheduled meetings. It also has to work seriously on decision making. Only after a slow continuous process of elaboration will it be possible to achieve concrete results which will in time lead to a shared, genuine, conscious and effective change. The process of goal planning meetings described by Sivaraman Nair et al. [22] could represent a valuable tool to be taken into consideration during the course of team self-constitution and growth.

The implications of our research for nursing management confirm that within health organizations attentive handling of team dynamics is crucial to thrive on team spirit. Whenever this aspect is neglected it is not unlikely to find situations as the one we described. The adoption of this type of investigation has to find practical application in the human resources management, in order to improve work quality environments. In this setting the objective will be to re-define the team roles within a specific care programme. This study has some limitations. The findings are related to the specific geographical, regional and national context of the Italian healthcare system. Further work is needed, aimed at extending analysis to functional rehabilitation centres with aspects different from our specific setting and gathering information about personal experiences through focus groups. In consideration of the results presented the most crucial and important point to face and deal with is that the key pre-requisite for any organizational change in the care of spinal cord injured people is the common acknowledgement of roles among all professionals.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest associated with this study. Neither the authors nor their families have received any special financial or other tangible benefit, including patent ownership, stock ownership, consultancies, or fees, in conjunction with the study.

AUTHOR’S DECLARATION

Authors confirm that the manuscript, the title of which is given above, is original, unpublished, and has not been submitted elsewhere. Authors acknowledge having contributed substantially to the preparation of the work described in the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by funding from the Piedmont Region within the 2006 Healthcare Research Plan. We are grateful for the support of the Hospital CTO/M. Adelaide, Turin - Italy, these organizations, their respective leaders and all health care professionals including physicians, nurses, rehabilitation and support staff working within the SCU.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Maria Giuseppina Teriaca for proofreading the manuscript.