All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Applying The Neuman Systems Model to Examine Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Extrapersonal Influences on Tuberculosis Treatment Adherence: A Mixed-methods Study

Abstract

Introduction

Treatment adherence remains a major challenge in tuberculosis (TB) control, particularly in low- and middle-income countries like Indonesia. Although TB treatment is provided free of charge, many patients still experience non-adherence due to various factors. This study examined the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extra personal factors influencing TB treatment adherence using an integrated mixed-methods approach guided by Neuman's systems model.

Methods

We employed a simultaneous mixed-methods design. Quantitative data were collected from 185 TB patients using a structured questionnaire assessing cognitive, psychosocial, and health system-related variables. Bivariate correlations and multivariate regression analyses were conducted to analyze factors influencing adherence across Neuman's domains. Qualitative data were generated through in-depth interviews with six purposively selected patients and were analyzed thematically. Findings from both approaches were integrated through joint interpretation to identify convergent and complementary patterns within the theoretical framework.

Results

In the multivariate analysis, shame was a significant negative intrapersonal predictor of adherence, while knowledge showed a significant trend. Family and social support served as protective interpersonal factors. Extrapersonal variables, such as healthcare support, had limited effects in the regression models. Qualitative findings highlighted emotional exhaustion, stigma, family support, and systemic barriers such as long wait times and limited follow-up as key influences. Integrated analysis showed that internal emotional struggles were the most prominent barrier. Supportive relationships and responsive healthcare services were important buffers.

Discussion

TB treatment adherence is shaped by cognitive and emotional processes at the intrapersonal level, reinforced by interpersonal support, and constrained by extrapersonal conditions. Integrating quantitative and qualitative evidence through Neuman's systems model clarifies how shame and forgetfulness undermine adherence, and how motivation and social support strengthen patients' adherence to treatment. Structural challenges are less evident in the statistical models but are articulated in patient narratives, highlighting the responsiveness of the system.

Conclusion

TB treatment adherence is an interaction between individual, relational, and systemic stressors. Neuman's systems model provides a useful framework for understanding these dynamics. Interventions that strengthen emotional resilience, increase caregiver engagement, and incorporate digital health strategies may improve adherence in similar settings.

1. INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a global health challenge. In 2023, approximately 7.5 million new cases were reported, up from 6.4 million in 2022 and 5.8 million in 2021. Despite various efforts, the number of new cases continues to rise annually. Not only is the number of new cases increasing, but TB is also a leading cause of death, with an estimated 1.30 million deaths worldwide. Indonesia, one of the countries with the second-highest mortality rate in the world, accounts for approximately 10% of global TB cases, increasing sharply from 93,000 in 2020 to 144,000 in 2021 [1,2].

One of the ongoing challenges in TB control is suboptimal treatment adherence. This suboptimal adherence is largely due to the lengthy duration of therapy. Adherence rates often decline during follow-up, especially as symptoms begin to improve. A meta-analysis found a 17-22% non-adherence rate in Asia [ 3 ]. Poor adherence leads to treatment failure and increased mortality. Non-adherence also contributes to the emergence of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB). At the community level, non-adherence contributes to a perpetual cycle of transmission and reinfection [ 4 ].

Previous research has identified various factors associated with non-adherence to TB treatment, including inadequate knowledge about the disease, side effects, socioeconomic barriers, stigma, and suboptimal patient-healthcare provider communication. This study also identified forgetfulness, psychological distress, lack of family support, and inadequate supervision by healthcare workers as key contributors to treatment adherence [ 4 ].

This study adopts Betty Neuman's systems model to conceptualize tuberculosis treatment adherence, viewing the patient as an open system exposed to intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal stressors. When these stressors are not adequately addressed, they can undermine patient resilience and disrupt medication-taking behavior. This research underscores the importance of a multidimensional approach that considers psychological, social, and structural factors in treatment non-adherence [ 5 ].

Although mixed-methods approaches have been widely applied to examine TB treatment adherence, many studies lack a guiding theoretical framework or treat the quantitative and qualitative components as separate investigations. Furthermore, few studies, particularly in Indonesia, have adopted a theoretically grounded, integrated mixed methods approach that combines statistical findings with patient perspectives to enrich the interpretation of results [6–11].

Therefore, this study aims to explore intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal stressors that influence TB treatment adherence using a simultaneous mixed methods design. The quantitative aspect includes bivariate and multivariate analyses to identify key correlates and predictors of treatment adherence, while the qualitative aspect captures patients' lived experiences. Guided by Neumann's systems model, the findings offer a more holistic understanding of adherence behavior and inform patient-centered intervention strategies.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design

This study employed a concurrent mixed-methods design to investigate the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal factors influencing TB treatment adherence [12]. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected simultaneously to allow complementary and contextual insights into the research problem. The quantitative component provided statistical associations across Neuman-based domains, whereas the qualitative component offered experiential explanations and contextual meaning derived from patients’ narratives. Integrating both strands within the Neuman systems model framework enabled a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of adherence behavior by combining population-level patterns with individual lived experiences, rather than treating them as separate lines of inquiry.

2.2. Study Setting

This study was conducted in six primary health centers located in Banyumas District, Central Java, Indonesia. The selected sites represented a deliberate range of geographic and sociodemographic contexts within the district. Baturraden I and Kemranjen I primary health centers were chosen to represent a mountainous rural area; Kembaran I and Sumbang I represented a peri-urban or suburban region; while Purwokerto Timur I and Purwokerto Barat represented an urban or city-center environment. The selection of these sites was intended to capture variation in patient experiences and differences in healthcare accessibility across different settings.

2.3. Participants and Sampling

For the quantitative strand, 185 TB patients were recruited via random sampling from three selected primary health centers in Banyumas District [13]. Eligible participants were adult patients (aged 18 years and above) undergoing either the intensive or continuation phase of TB treatment and who provided informed consent to participate. Patients who were unable to communicate effectively, exhibited cognitive impairments, or had serious medical complications were excluded from the study to ensure the validity and reliability of responses.

For the qualitative component, six participants were purposively selected based on their treatment outcomes. Specifically, patients who remained sputum-positive after 2 months of treatment, as indicated by an acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear, were invited to participate in in-depth interviews. This subgroup was chosen to explore in greater depth nonadherence-related experiences and barriers to treatment, thereby providing interpretive context to the quantitative findings. Although the sample included only six participants, this size is appropriate for an in-depth, theory-guided inquiry, as purposive selection of sputum-positive patients yields information-rich cases. In qualitative research, depth of insight-rather than sample size-determines adequacy.

2.4. Data Collection and Instruments

For the quantitative phase, data were collected using a structured questionnaire comprising both standardized and self-developed instruments. Medication adherence was measured using the 8-item Morisky medication adherence scale (MMAS-8), a widely validated tool that assesses patients’ adherence behaviors through recall and treatment-taking behaviors [14].

Other independent variables-including knowledge, awareness about illness, motivation, feeling ashamed, forgetfulness, frustration due to long therapy, perceived side effects, stigma, family support, social support from friends and community, and health care support (education, counseling, supervision, and motivation)-were measured using self-developed questionnaire items. These items were constructed through an iterative literature-informed process.

Before data collection, the instrument underwent content validity assessment by a panel of experts and construct reliability testing using Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.71–0.84), indicating acceptable internal consistency across all subscales. Questionnaires were administered in person to eligible respondents during clinic visits at the selected health centers, with assistance provided when needed to ensure comprehension and completeness.

For the qualitative phase, data were collected using a semi-structured interview guide developed by the research team. The guide was designed to explore patients’ personal experiences during TB treatment, including intrapersonal, interpersonal, and systemic factors influencing adherence-such as psychological responses, family or social influences, medication-related discomfort, and experiences with health services. Theoretical constructs and preliminary field observations informed the guide's content. In-depth face-to-face interviews were conducted in a private setting by trained interviewers, and all sessions were audio-recorded with participants' consent for transcription and subsequent thematic analysis.

2.5. Data Analysis and Integration

Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS version 21. Pearson’s correlations and multiple linear regressions were used to examine associations and predictors of TB medication adherence across intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal variables based on the Neuman systems model. Model diagnostics assessed normality, autocorrelation, and multicollinearity. Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Qualitative data were thematically analyzed using NVivo 12, following Braun and Clarke’s six-step framework [15]. Transcripts were coded inductively and deductively, then grouped into themes aligned with Neuman’s domains. An integrative phase compared and synthesized both strands through a joint display and narrative structured by the Neuman model, highlighting convergences, divergences, and complementary insights.

The Neuman systems model served as an analytic framework for structuring both the quantitative and qualitative strands. In the quantitative analysis, intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal variables were mapped onto Neuman’s lines of defense to examine how proximal cognitive–emotional pressures and more distal relational or institutional stressors influence adherence. For the qualitative strand, deductive coding was guided by Neuman’s concepts of flexible, normal, and resistance lines of defense to interpret patients’ responses to stressors. During integration, the model provided a system-level structure for linking statistical associations with lived experiences across the three domains.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee of Universitas Muhammadiyah Purwokerto (Approval No. KEPK/UMP/03/IX/2025). All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments, or with comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants after providing information about the study’s objectives, procedures, risks, and benefits. Participants were assured of confidentiality and the voluntary nature of their participation.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of Respondent

Among the 185 participants included in the quantitative strand, the majority were male (59.5%) with a mean age of 42.2 ± 15.0 years. Most respondents had a high school education (48.6%), followed by middle school (29.2%) and elementary school (15.7%). Regarding employment, 40.5% were laborers, while 27.0% were unemployed. Nearly half of the participants had been undergoing TB treatment for approximately 2–4 months. At the end of the intensive treatment phase (2 months), 90.3% of participants demonstrated sputum conversion to negative results (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 110 (59.5%) |

| Female | 75 (40.5%) |

| Age, mean±SD, yr | 42.2±15.0 |

| Education | |

| Elementary School | 29 (15.7%) |

| Middle School | 54 (29.2%) |

| High School | 90 (48.6%) |

| Bachelor's Degree | 12 (6.5%) |

| Employed | |

| Unemployed | 50 (27.0%) |

| Laborer | 75 (40.5%) |

| Farmer | 25 (13.5%) |

| Civil Servant | 6 (3.3%) |

| Self-Employed | 29 (15.7%) |

| Treatment Duration, months | |

| 2-4 | 90 (48.7%) |

| 5-6 | 43 (23.3) |

| >6 | 52 (28.0%) |

| Sputum examination in the first 2 months | |

| Positive | 18 (9.7%) |

| Negative | 167 (90.3%) |

The six participants in the qualitative strand consisted of four males and two females, with a mean age of 45.3 ± 7.8 years. Their educational backgrounds ranged from elementary to bachelor’s degrees, and their employment status was evenly split between unemployed and self-employed. Treatment duration was similarly distributed across 2–4 months, 5–6 months, and more than 6 months, reflecting a range of treatment experiences.

3.2. Quantitative Findings

3.2.1. Bivariate Correlation Analysis

Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine associations between medication adherence and intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal factors based on the Neuman systems model. Among the six intrapersonal variables, knowledge about TB showed a moderate positive and statistically significant correlation with adherence (r = 0.238, p = 0.001). Awareness (r = 0.174, p = 0.018) and motivation (r = 0.177, p = 0.016) also demonstrated statistically significant positive associations.

Conversely, feeling ashamed was significantly negatively correlated with adherence (r = –0.210, p = 0.004). Forgetfulness (r = –0.152, p = 0.039) and frustration (r = –0.188, p = 0.010) also showed significant negative correlations. In the interpersonal domain, social support was moderately correlated with adherence (r = 0.220, p = 0.003), followed by family support (r = 0.154, p = 0.037). In contrast, side effects (r = –0.185, p = 0.012) and perceived stigma (r = –0.175, p = 0.017) were negatively correlated with adherence.

In the extrapersonal domain, health care support, encompassing patient education, counseling, and supervision, was positively correlated with adherence (r = 0.158, p = 0.032), underscoring the role of systemic and institutional support (Table 2 for full bivariate results).

| Variable | r | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | ||

| Knowledge | 0.238 | 0.001 |

| Awareness of his illness | 0.174 | 0.018 |

| Motivation | 0.177 | 0.016 |

| Feeling ashamed | -0.210 | 0.004 |

| Forgetfulness | -0.152 | 0.039 |

| Frustration about long therapy | -0.188 | 0.010 |

| Interpersonal | ||

| Side effects | -0.185 | 0.012 |

| Stigma | -0.175 | 0.017 |

| Family support | 0.154 | 0.037 |

| Social support (friends and community) | 0.220 | 0.003 |

| Extrapersonal | ||

| Health care support (education, counseling, supervision, and motivation) | 0.158 | 0.032 |

3.2.2. Multivariate Regression Analyses

Multiple linear regression examining intrapersonal variables (Table 3, Model 1) showed a significant model (F(6,178) = 3.901, p = 0.001), explaining 11.6% of variance in adherence. Feeling ashamed was the only significant predictor (β = –0.181, p = 0.016). Knowledge approached significance (β = 0.215, p = 0.085). Model diagnostics indicated normally distributed residuals (D’Agostino p = 0.0026), no serious autocorrelation (Durbin–Watson = 1.92), and no multicollinearity (VIF < 3).

The second model examined contextual factors (side effects, stigma, family support, social support, and health care support) (Table 3, Model 2). This model was significant (F(5,179) = 3.782, p = 0.003), explaining 9.6% of the variance in adherence. Side effects were marginally associated with adherence (β = –0.144, p = 0.052). Stigma (β = –0.126, p = 0.087) and social support (β = 0.176, p = 0.074) approached significance. Healthcare support was non-significant. Model diagnostics showed a slight deviation from normality (D’Agostino p < 0.0001), but no autocorrelation (Durbin–Watson = 1.66) or multicollinearity (VIF < 2).

| Predictor | B | SE | β | t | p-value | 95% CI for B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | (Constant) | 6.222 | 1.203 | 5.174 | 0.000 | 3.849-8.595 | |

| Knowledge | 0.063 | 0.036 | 0.215 | 1.733 | 0.085 | -0.009-0.134 | |

| Awareness | 0.001 | 0.034 | 0.002 | 0.017 | 0.987 | -0.066-0.067 | |

| Motivation | 0.006 | 0.043 | 0.014 | 0.150 | 0.881 | -0.079-0.091 | |

| Feeling ashamed | -0.056 | 0.023 | -0.181 | -2.441 | 0.016 | -0.101--0.011 | |

| Forgetfulness | -0.018 | 0.038 | -0.055 | -0.470 | 0.639 | -0.093-0.057 | |

| Frustration | -0.021 | 0.029 | -0.085 | -0.723 | 0.471 | -0.078-0.036 | |

| Model 2 | (Constant) | 6.893 | 1.183 | 5.827 | 0.000 | 4.558-9.227 | |

| Side effects | -0.040 | 0.020 | -0.144 | -1.954 | 0.052 | -0.080-0.000 | |

| Stigma | -0.039 | 0.023 | -0.126 | -1.722 | 0.087 | -0.083-0.006 | |

| Family support | 0.011 | 0.028 | 0.035 | 0.401 | 0.689 | -0.043-0.065 | |

| Social support | 0.127 | 0.071 | 0.176 | 1.797 | 0.074 | -0.013-0.268 | |

| Health care support | 0.006 | 0.032 | 0.018 | 0.187 | 0.852 | -0.058-0.070 | |

| Model 3 | (Constant) | 5.970 | 1.511 | 3.951 | 0.000 | 2.988-8.952 | |

| Knowledge | 0.103 | 0.054 | 0.353 | 1.929 | 0.055 | -0.002-0.209 | |

| Awareness | -0.011 | 0.035 | -0.037 | -0.306 | 0.760 | -0.080-0.059 | |

| Motivation | -0.002 | 0.074 | -0.003 | -0.020 | 0.984 | -0.148-0.145 | |

| Feeling ashamed | -0.053 | 0.047 | -0.171 | -1.121 | 0.264 | -0.145-0.040 | |

| Forgetfulness | -0.014 | 0.043 | -0.043 | -0.325 | 0.746 | -0.099-0.071 | |

| Frustration | -0.030 | 0.065 | -0.122 | -0.464 | 0.643 | -0.157-0.097 | |

| Side effects | -0.005 | 0.041 | -0.018 | -0.123 | 0.902 | -0.087-0.077 | |

| Stigma | 0.013 | 0.063 | 0.041 | 0.200 | 0.842 | -0.112-0.138 | |

| Family support | -0.059 | 0.049 | -0.185 | -1.191 | 0.235 | -0.157-0.039 | |

| Social support | 0.048 | 0.086 | 0.066 | 0.555 | 0.580 | -0.122-0.217 | |

| Health care support | 0.011 | 0.045 | 0.034 | 0.249 | 0.803 | -0.078-0.101 | |

Note: Model diagnostics model 1: F(6,178) = 3.901, p = 0.001; R2 = 0.116; Adjusted R2 = 0.086; Durbin-Watson = 1.92; Normality (D’Agostino & Pearson) = p = 0.0026; Multicollinearity (VIF) < 3. Model diagnostics model 2: F(5,179) = 3.782, p = 0.003; R2 = 0.096; Adjusted R2 = 0.070; Durbin-Watson = 1.66; Normality (D’Agostino & Pearson) = p = 0.0001; Multicollinearity (VIF) < 2. Model diagnostics model 3: F(11,173) = 2.354, p = 0.010; R2 = 0.130; Adjusted R2 = 0.075; Durbin-Watson = 1.65; Normality (D’Agostino & Pearson) = p = 0.0001; Multicollinearity (VIF) mostly < 5, except for frustration about long therapy (VIF = 13.78) and stigma (VIF = 8.43).

The final model (intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal) (Table 3, Model 3) was significant (F(11,173) = 2.354, p = 0.010), explaining 13.0% of variance. Knowledge approached significance (β = 0.353, p = 0.055). Other predictors were not significant when controlling for all variables. Model diagnostics showed slight deviations from normality, no major autocorrelation (Durbin–Watson = 1.65), and acceptable multicollinearity except frustration (VIF = 13.78) and stigma (VIF = 8.43) (Table 3 for full coefficients).

3.3. Qualitative Findings: Patient Experiences and Barriers to Tuberculosis Treatment Adherence

Table 4 presents a thematic synthesis of qualitative findings based on the Neuman systems model, summarizing patient narratives across intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal domains. Each main theme is supported by specific subthemes, key descriptive points, and illustrative participant quotes that reflect the lived experience of TB treatment. This structured approach not only highlights psychological and behavioral responses but also captures key systemic facilitators and barriers to adherence as perceived by patients.

3.3.1. Theme 1: Patients’ Experiences during TB Treatment

Participants described a dynamic process of adaptation following diagnosis. Initial reactions often involved denial or disbelief, especially in the absence of overt symptoms. Patients experienced physical discomfort such as nausea and fatigue during the early treatment phase, but over time, they gradually developed acceptance and adjusted their daily routines. As their physical condition improved-marked by increased appetite and weight gain-patients began to view the lengthy treatment duration as a manageable and necessary commitment.

3.3.2. Theme 2: Perceived Side Effects and Coping Strategies

Although most participants experienced mild side effects such as nausea, itching, or dark-colored urine, these were generally tolerated. A minority reported disruptions to daily life or brief temporary discontinuation of treatment due to side effects. Patients actively sought assistance from health workers, either through direct visits or digital communication. Timely responses from health providers, including reassurance and additional medications, helped maintain adherence and reduced anxiety related to side effects.

| Main Theme | Sub-theme | Key Points | Representative Quote | Neuman Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients’ experiences during TB treatment | Early adaptation to diagnosis and treatment | Initial denial due to lack of symptoms; emotional shock; physical adjustment (nausea, weakness, loss of appetite); difficulty adjusting to medication routines. | “At first I didn’t believe it because I felt nothing. The first weeks were hard-nausea, weak body, no appetite.” (Inf-4) | Intrapersonal |

| Acceptance of TB diagnosis | Acceptance emerged gradually after repeated tests or administrative needs (e.g., overseas work); realization that TB is treatable with adherence. | “I finally believed it after the lung specialist confirmed it. I realized I had to follow the treatment to get better.” (Inf-3) | Intrapersonal | |

| Challenges and strategies in managing treatment | Struggles to maintain routines due to activities or side effects; reliance on self-discipline; no digital reminders; intrinsic responsibility for recovery. | “Sometimes I’m busy and almost forget, but I make time. I rely on discipline because I want to recover.” (Inf-2) | Intrapersonal | |

| Physical and psychological improvements | Increased appetite, weight gain, improved stamina; acceptance of long treatment duration as part of recovery. | “After a few months, my appetite returned, and my weight increased. I accepted the six-month treatment.” (Inf-1) | Intrapersonal | |

| Experiences with medication side effects and coping strategies | Types and intensity of side effects | Nausea, itching, bitter taste, discoloration of urine; variation in severity; some experience no side effects at all. | “If I take all six pills at once, I vomit immediately… even water tastes bitter.” (Inf-3) | Interpersonal |

| Impact on daily activities | Most side effects are tolerable; a few require temporary treatment interruption; tolerance levels vary. | “The nausea made me stop for a moment, but usually it doesn’t disturb my activities.” (Inf-6) | Intrapersonal | |

| Patient coping responses | Consulting health workers, reporting via WhatsApp, medication adjustments, and additional symptomatic treatment. | “I reported it to the health center, and they advised what to do. Sometimes I contacted the doctor on WhatsApp.” (Inf-5) | Interpersonal | |

| Role of health workers | Quick responses, reassurance about normal reactions, and additional medications to manage symptoms enhance the patient's sense of safety. | “They said it was normal and gave extra medicine for the itching. Their quick response helped a lot.” (Inf-4) | Extrapersonal | |

| Access to and quality of health services | Ease of access | Most patients found the health center accessible, had regular visits before medication ran out, and had no major transport issues. | “It’s easy to reach the health center… I always go before my medicine runs out.” (Inf-2) | Extrapersonal |

| Barriers to access and service flow | Long waiting times (2–4 hours), insurance inactive issues, and administrative constraints, rather than distance. | “The main problem is the long queue… sometimes 2 hours.” (Inf-3) | Extrapersonal | |

| Perceptions of service quality | Services are perceived as good, helpful, and friendly; some still hope for faster and more efficient processes. | “The service is good and helpful, but I hope it can be faster and less complicated.” (Inf-1) | Extrapersonal | |

| Expectations toward health services | Desire for faster, friendlier, more efficient services; stronger monitoring to maintain motivation. | “I hope the health center can be faster and not complicated… and the staff can monitor us more closely.” (Inf-6) | Extrapersonal | |

| Health worker support as an adherence reinforcement | Forms of support | Appointment reminders, home visits, and WhatsApp communication; accessible health workers provide comfort during a long treatment regimen. | “They reminded me about the schedule and even visited at home. It really helped.” (Inf-2) | Extrapersonal |

| Impact on adherence | Support is perceived as caring and motivating; those without reminders feel less attended to; emotional reassurance increases commitment. | “I feel motivated because they care… but some friends didn’t get reminders.” (Inf-5) | Interpersonal | |

| Patient adherence and self-management strategies | Reminder strategies and adaptation | Use of alarms, daily routines, and family reminders; limited use of digital tools, but openness toward future apps. | “I use my own alarm… sometimes my wife reminds me. I’m open to using an application.” (Inf-1) | Intrapersonal / Interpersonal |

| Consistency of medication intake | Most maintain consistent daily schedules; occasional delays are compensated promptly; no intentional missed doses. | “Sometimes I’m late by an hour, but I still take it. I’ve never skipped on purpose.” (Inf-3) | Intrapersonal | |

| Motivation and self-awareness | Internal motivation: responsibility, fear of relapse, desire for recovery, not wanting to burden family; administrative needs (e.g., work abroad). | “I want to recover and not trouble my family… I’m afraid the disease will come back.” (Inf-4) | Intrapersonal | |

| Family and health worker roles in adherence | Family-especially spouses and mothers-support consistency; health workers motivate but rarely provide daily reminders. | “My wife always reminds me. The health workers motivate me when I come for control.” (Inf-6) | Interpersonal |

3.3.3. Theme 3: Access and Perceptions of Healthcare Services

Most participants reported easy physical access to public health centers and described healthcare providers as approachable and helpful. However, long wait times and issues with insurance activation emerged as important service barriers. Despite these challenges, overall satisfaction with service quality remained high, with participants appreciating the staff's friendliness and efficiency. They also voiced expectations for faster, less bureaucratic processes and more consistent provider follow-up.

3.3.4. Theme 4: Health Worker Support as a Facilitator of Adherence

Participants viewed health worker support not only as technical assistance but also as a source of emotional encouragement. This included medication reminders, home visits, and proactive communication via WhatsApp. Patients who received this support felt cared for and motivated to adhere. Conversely, those who did not receive digital reminders felt overlooked, though many remained self-disciplined.

3.3.5. Theme 5: Strategies and Determinants of Adherence

Patients reported high levels of adherence, driven by intrinsic motivation and a sense of responsibility for their own health. Reminder strategies included using alarms, establishing fixed medication times, and involving family members. Most patients demonstrated consistent medication-taking behavior, though some experienced occasional delays. Fear of disease recurrence and the desire for a full recovery were prominent drivers of adherence. Family members, particularly spouses and mothers, played a key role in providing reminders and emotional support.

3.4. Joint Interpretation of Findings based on The Neuman Systems Model

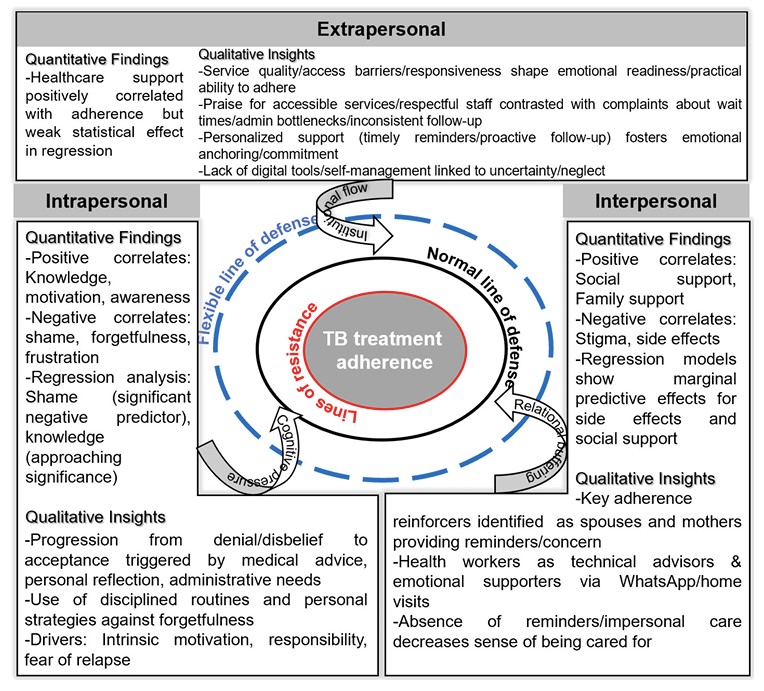

Figure 1 illustrates the integrated interpretation of quantitative and qualitative findings on TB treatment adherence, guided by the Neuman systems model. Each domain-intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal-is connected to the patient’s core defense systems (Flexible line of defense, Normal line of defense, and Lines of resistance). Arrows represent directional pressures that influence adherence behaviors: cognitive pressure, relational buffering, and institutional flow.

Integrated joint interpretation of TB treatment adherence based on Neuman's systems model.

4. DISCUSSION

This study employed a mixed-methods approach to gain a deeper understanding of TB treatment adherence. Guided by the Neumann systems model theoretical framework, this study employed a simultaneous mixed-methods approach, combining both quantitative and qualitative methods to analyze how psychological, relational, and systemic stressors interact to shape patient behavior.

In this study, the intrapersonal domain emerged as the strongest and most consistent influence on TB treatment adherence. The quantitative analysis revealed that knowledge, awareness, and motivation were positively associated with adherence, while shame, forgetfulness, and frustration were negatively associated [16–20]. Among these variables, shame was the only significant predictor in the multivariate regression analysis, while knowledge approached significance but should be interpreted with caution, suggesting the potential role of cognitive mechanisms influencing adherence [17,21]. The frustration and stigma variables, which exhibited high VIF values, reflect overlap among related emotional constructs; this overlap, while commonly observed in psychosocial research, may slightly impact the precision of the multivariate estimates.

The qualitative findings provide contextual depth to this study. Patients described an emotional transition from denial, uncertainty, and fear to gradual acceptance as they interacted with healthcare providers, reflected on their own experiences, or adapted to administrative requirements. The results of this study were very similar to those reported in previous mixed-methods studies [6,7,22]. Patients also demonstrated active coping strategies-using alarms, setting fixed treatment times, reframing illness perceptions, and relying on intrinsic motivation-that align with research linking coping and self-regulation to medication adherence [23,24].

Theoretically, the patterns found in this study align with Neuman's flexible line of defense, in which internal resilience, cognitive appraisal, and emotional regulation serve as primary protective mechanisms against stressors [5]. Within this framework, shame, frustration, and persistent fear of illness serve as intrapersonal stressors that weaken the flexible line of defense and decrease adherence, while knowledge, motivation, and self-regulation strategies strengthen the line of resistance, improving treatment adherence [16–19,25]. Therefore, providing psychological counseling, stigma reduction, and motivational strategies are important components of intrapersonal-level interventions [24,26].

This study also found that interpersonal factors significantly influence adherence, although the statistical effects were more moderate. Quantitative findings showed that family and social support were positively correlated with adherence, while stigma and side effects were negatively correlated [16,27–30]. Although these variables showed only marginal effects in multivariate models, qualitative findings clearly illustrate their importance.

Patients identified strong emotional support-particularly from partners, mothers, siblings, and healthcare professionals-as an important motivator for adherence. This emotional support manifested itself in the form of medication reminders, motivational support, and consistent communication. These findings support previous research across various cultures and countries [6–8,10,11,31]. Quality interpersonal interactions, particularly with healthcare professionals, also help stabilize patients emotionally and strengthen medication adherence [22,27–30].

In contrast, interpersonal stigma manifests not only as emotional distress but also as concealment behaviors, such as avoiding treatment or disclosing one's condition. This is consistent with previous research linking stigma to treatment non-adherence [17,21,32]. However, trust in healthcare providers gradually shapes adherence behavior, suggesting that relational continuity and provider commitment influence treatment engagement [33,34].

In Neuman's systems model, interpersonal support functions as a stabilizing buffer that moderates the impact of external and emotional stressors on the patient's defense system [ 5 ]. In this study, family support and healthcare services served as interpersonal buffering mechanisms that stabilize the normal defense line against treatment-related stressors. Therefore, strengthening caregiver engagement and improving structured communication within the family can improve patient treatment consistency.

The extrapersonal domain of this study demonstrates the clearest discrepancy between quantitative and qualitative findings. In the quantitative analysis, healthcare support-which includes patient education, counseling, and supervision-was positively correlated with adherence but became insignificant in the regression model. This finding aligns with findings in other studies where system-level variables are not well captured by structured assessments [3,8,35].

In contrast, the qualitative findings found substantial structural effects on adherence. Patients described long wait times, insurance issues, limited provider availability, and inconsistent follow-up-barriers frequently found across Asia and Africa in previous studies [6–8,10,16,22,36]. These systemic issues disrupt patients' daily routines, increase frustration, and reduce motivation for adherence. Paradoxically, however, many patients still expressed high satisfaction with services, despite these structural barriers, due to friendly staff and accessible facilities, suggesting a complex interplay between structural barriers and interpersonal experiences.

Patients also reported that personalized and responsive services-such as WhatsApp reminders, proactive communication, and home visits-can improve their emotional well-being and adherence. These findings are consistent with growing evidence that digital adherence technologies, including SMS reminders, video-observed therapy, and electronic pill boxes, can improve medication consistency when appropriately integrated into clinical workflows [37–41].

Overall, the results of this study indicate that extrapersonal stressors significantly influence adherence behavior, even when they are not detected as significant predictors in the quantitative model. Within Neuman's framework, institutional characteristics and structural conditions act as distant but powerful determinants of system resilience and stability [5,6]. In this study, waiting time and administrative barriers serve as extrapersonal stressors that disrupt normal lines of defense, while responsive services and digital support help restore system stability. Thus, increasing service responsiveness, reducing administrative barriers, enhancing follow-up mechanisms, and integrating context-appropriate digital support tools are essential components of extrapersonal-level interventions.

Collectively, the integrated findings show that intrapersonal cognitive–emotional mechanisms form the core of adherence behavior; interpersonal relationships serve as relational buffers that may reinforce or weaken this core; and extrapersonal structures establish the broader institutional environment in which adherence occurs. These domains do not operate in isolation. Rather, they interact dynamically: interpersonal support and institutional responsiveness continuously shape how intrapersonal defenses-knowledge, motivation, coping, and emotional regulation-respond to treatment-related stressors.

The Neuman systems model provides a coherent framework for interpreting these multilevel interactions by conceptualizing flexible, normal, and resistance lines of defense [5]. By integrating data across intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal domains, the model offers a nuanced lens for understanding how stressors and supports influence medication-taking behavior.

Finally, this study demonstrates the value of a mixed-methods approach in uncovering statistical patterns and lived experiences, consistent with the strengths of previous integrative mixed-methods research [4, 6-8, 10, 12, 42]. Therefore, tailoring interventions across these three domains can provide a comprehensive blueprint for designing a holistic, patient-centered TB care system that strengthens adherence.

5. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

Strengths of this study include its complementary mixed-methods design, clear theoretical foundation, and direct incorporation of patient voices. Limitations include the relatively small qualitative sample and the single-district setting, which may limit its applicability to other studies. In the quantitative analysis, two intrapersonal variables (frustration and stigma) exhibited high VIF values, indicating multicollinearity that may slightly reduce the precision of the regression estimates. Furthermore, this study relied on self-reported measures of adherence, which may introduce recall bias. Future research should adopt a multi-site longitudinal design to validate these findings and better clarify causal pathways.

CONCLUSION

This mixed-methods study reveals that tuberculosis treatment adherence is shaped by a complex interplay of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and extrapersonal factors, as conceptualized in Neuman's systems model. The intrapersonal domain-specifically shame, knowledge, and emotional readiness-emerged as the most influential, with adherence behavior reflecting the dynamic tension between psychological stressors and internal coping capacities. The interpersonal domain emphasized the role of emotionally resonant support, where the consistency and quality of relationships involving family and healthcare workers served as important buffering mechanisms against treatment fatigue and stigma. Extrapersonal influences, although statistically modest, were strongly reflected in patient narratives, particularly regarding service accessibility, waiting times, continuity of care, and digital engagement.

By integrating quantitative and qualitative insights, this study demonstrates how internal vulnerabilities, the relational environment, and systemic structures collectively influence adherence behavior. Neuman's systems model provides a coherent and useful framework for interpreting these interactions and highlights critical defense mechanisms at multiple system levels. These findings underscore the need for multidimensional, patient-centered interventions-such as stigma reduction, motivational counseling, family engagement, and service innovations using digital tools-that can strengthen resilience and improve TB treatment adherence.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: A.S.: Conceptualized the study, selected the theoretical framework, and designed the mixed-methods approach; S.: Conducted and analyzed the quantitative and qualitative data; N.J. and T.P.: Supervised the methodology and provided ongoing critical input throughout the research process; R.D.S.: Contributed to the development of the interview guide, qualitative coding, and thematic refinement; S.: Drafted the initial manuscript, including the introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion; J. and P.: Reviewed and revised the manuscript for intellectual content and consistency with international standards. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. Juniarti provided overall academic supervision and project oversight.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| AFB | = Acid-Fast Bacilli |

| MDR-TB | = Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis |

| MMAS-8 | = Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (8-item) |

| NVivo | = Qualitative data analysis computer software package |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TB | = Tuberculosis |

| VIF | = Variance Inflation Factor |

| XDR-TB | = Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee of Universitas Muhammadiyah Purwokerto (Approval No. KEPK/UMP/03/IX/2025).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments, or with comparable ethical standards.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all participants after providing information about the study’s objectives, procedures, risks, and benefits. Participants were assured of confidentiality and the voluntary nature of their participation.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

FUNDING

This research was financially supported by Universitas Muhammadiyah Purwokerto for study implementation, including data collection and analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their gratitude to the tuberculosis patients and healthcare professionals who participated in the study. Appreciation is also extended to the Banyumas district health office and primary health center staff for their support during data collection. We would also like to acknowledge the valuable assistance of nursing students who supported data collection: Azza Hikmatul Maula, Ilham Riski Nasrulloh, Shinta Mutiara Zahrani, and Melani Rahma Andini. Appreciation is also extended to Universitas Padjadjaran and Universitas Muhammadiyah Purwokerto for their institutional support.