All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

A Cross-Sectional Study Examining the Factors that Influence the Perception of Stress Among Intensive Care Unit Nurses in Jordan

Abstract

Background

Intensive care units are characterized by high levels of responsibility and exposure to psychological stress. This study aimed to explore the relationship between perceived stress, psychological resilience, and sociodemographic variables of intensive care unit registered nurses in Jordan, as well as the predictors of perceived stress.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted between January 5th and February 20th, 2025, and included 200 participants (88 males and 112 females) aged 23–51, from selected public and government hospitals located in Amman and Madaba, Jordan. Nurses’ sociodemographic characteristics were obtained, and the Perceived Stress Scale-10 and Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 were administered. Statistical analyses included Pearson correlation, independent t-test, one-way ANOVA, and multiple linear regression.

Results

A significant inverse relationship was observed between perceived stress and psychological resilience. Bivariate analysis indicated that nurses’ age and experience had a significant positive relationship with perceived stress. Nurses who were female, single, of other marital status, worked a 16-hour shift system, worked extra hours, had an uncomfortable work environment, and experienced equipment shortages reported significantly higher perceived stress. Multiple linear regression indicated that working extra hours, working in an uncomfortable work environment, shift work, and being single or of other marital status collectively explained 40.4% of the variance in perceived stress scores. The strongest predictor was working extra hours, which was associated with an average increase of 2.80 units and explained 8.35% of the variance. Furthermore, working in uncomfortable workplaces was associated with an average increase of 2.116 units in perceived stress scores, accounting for 4.28% of the variance. The multiple linear regression model accurately predicted perceived stress scores 95.0% of the time, with up to 85.0% sensitivity and 78.0% specificity.

Conclusion

The findings indicate an inverse relationship between perceived stress and psychological resilience. However, workload, shift length, extra working hours, and workplace environment conditions contributed significantly to ICU nurses’ levels of stress.

1. INTRODUCTION

Identifying the factors that influence perceived stress is a focus of research on mental health [1-3]. Stress, a normal response arising when facing challenges, is characterized by negative emotional, physical, and behavioral responses due to an individual’s inability to cope. Perceived stress reflects the relationship between people and the environment, which they appraise as endangering or overtaxing their resources, and it may impact their well-being [4]. Previous studies have indicated that healthcare providers’ work environments and sociodemographic characteristics are significantly correlated with their stress [5-7]. Work can be demanding and stressful for nurses working in acute care settings, such as emergency departments and intensive care units (ICU) [8]. ICU nurses experience a significant level of stress owing to end-of-life care, complex life-support procedures, and painful interventions during patient care [9]. The prevalence of stress among nurses and ICU nurses is approximately 9–68% and 68.29% globally, respectively, and varies across different countries [10, 11].

Multifaceted work-related stressors can disrupt nurses’ physical and mental wellbeing, increase stress, and decrease work productivity [12, 13]. Psychological resilience constitutes a nurse's ability to adapt to or cope positively with perceived stress as a coping strategy [14, 15]. Resilience predicts depression, anxiety, and stress [16] and protects nurses from mental health distress [17]. Furthermore, it is considered an essential and effective method for overcoming various challenges and stressors, including work-related difficulties [16, 18].

Correlational studies on job performance, stress, and resilience have revealed a negative relationship between job performance and stress, a positive relationship between resilience and stress, and a moderately positive relationship between stress and resilience [18]. Peñacoba et al. reported that a higher perception of self-efficacy was associated with increased resilience and a lower perception of stress [19]. Additionally, increased resilience was associated with improved physical health and mental well-being. Similarly, Talebian et al. reported a positive relationship between resilience and moral distress, indicating that ICU nurses used resilience as a coping strategy when moral distress increased [20]. Psychological empowerment of ICU nurses significantly improved after resilience training compared with before the intervention [8, 21].

Furthermore, research findings indicate correlations between job performance, perceived stress, and resilience among ICU nurses. Ta’an et al. found a negative correlation between job performance and stress, and a positive correlation between resilience and stress [18]. Another study reported that nurses experienced moderate levels of stress but demonstrated high levels of resilience, with a significant relationship observed between stress, resilience, and turnover intention [22]. During the pandemic, the relationship between stress and resilience among ICU nurses had a psychological impact on nursing. Almegewly et al. found that although nurses in the critical care unit reported stress, there was no correlation between stress and resilience; furthermore, 64% of participants indicated moderate levels of stress [23].

Although significant stress levels were noted in the emergency room (ER), most neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) nurses reported feeling extremely stressed. Nurses had high confidence in their ability to manage issues related to infection. Almegewly et al. reported that even after the number of COVID-19 cases dropped, most nurses still experienced moderate-to-high stress levels linked to the pandemic and demonstrated reasonable resilience [23]. Aqtam et al. reported that most ICU nurses experienced high stress levels and low resilience. Aqtam also found negative correlations between stress and resilience, as well as between nurses’ stress subscales and resilience [6].

Hence, examining nurses’ stress and resilience is essential for understanding how workplace challenges impact perceived stress, which can vary based on psychological resilience. Stressors may lead to mental health issues, such as fear, depression, and anxiety, among ICU nurses [6]. Previous studies have mainly examined stress levels among ICU nurses and their coping strategies. However, few studies have addressed work-related stressors in relation to stress and resilience among ICU nurses in Jordan, using the PSS-10 and CD-RISC-10 scales concurrently. This study aimed to explore the relationship between perceived stress, psychological resilience, and sociodemographic variables of ICU nurses in Jordan, identify predictors of perceived stress, and assess the model for accuracy.

2. METHODS

2.1. Setting, Population, Sample, and Data Collection

This cross-sectional study was conducted at three major hospitals in Amman and Madaba, Jordan, which represented the most common types of ICUs in Jordan. Participating nurses worked in the medical, surgical, and cardiac ICUs and were recruited via convenience sampling. Al-Bashir Hospital, Prince Hamzah Hospital, and Al-Nadeem Hospital have 88, 27, and nine ICU beds, respectively.

The Inclusion criteria were nurses who (a) were registered and had a minimum experience of one year in the ICU, (b) currently worked in the ICU unit, and (c) had a bachelor's degree. Exclusion criteria were (a) pediatric ICU nurses and (b) nurses with previous administration experience.

Sample size was determined via Slovin's formula, which was computed as n = N / (1+Ne2). Considering sample size (n), population size (N), and margin of error (e 0.05), 200 nurses were required from the 389 nurses in the selected hospitals. Slovin's formula was used to calculate sample size when the size of the target population was known [24].

After ethical and formal approval were obtained, a formal request was submitted to the heads of ICU nurses of the three participating hospitals. All ICUs received brochures that covered the study’s purpose, significance, risks and benefits, and inclusion and exclusion criteria. Furthermore, they were informed that the survey would take between 15–20 minutes to complete. The proposed participants received handouts that included the researcher’s name and telephone number. Nurses who agreed to participate met the researcher, who explained the questionnaires, and subsequently signed an informed consent form. Three sheets were provided to the participants: sociodemographic, Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10), and Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (CD-RISC-10). The questionnaires used for data collection were in English because the nurses’ education was in English; furthermore, the work setting required English for communication. The researcher, present in a designated area of the hospital, received the completed forms and reviewed them to ensure that all items were marked. Participants were identified using codes: AL-Bashir Hospital (A1, A2, A3 …), Prince Hamza Hospital (B1, B2, B3 …), and AL-Nadeem Hospital (C1, C2, C3 …), with no names recorded. Data were collected between January 5 and February 20, 2025, and entered into an Excel sheet upon receipt of the questionnaires.

2.2. Study Measures

2.2.1. Demographic Characteristics

Participants’ sociodemographic variables, including age, gender, marital status, years of work experience, hospital workplace, and work stressors, were collected Table 1.

| Variables | Frequencies | Percentages | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 33.15 (5.23) 23–51 |

||

| Work experience in years | 7.25 (3.38) 1–20 |

||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 88 | 44.0 | |

| Female | 112 | 56.0 | |

| Participants’ workplace | |||

| AL Basheer hospital | 127 | 63.5 | |

| Prince Hamza hospital | 61 | 30.5 | |

| AL-Nadeem hospital | 12 | 6.0 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 100 | 50.0 | |

| Single | 68 | 34 | |

| Others | 32 | 16 | |

| Work stressors | |||

| Shift work | |||

| 8 hours | 103 | 51.5 | |

| 16 hours | 97 | 48.5 | |

| Participants worked extra hours in the ICU | |||

| Yes | 123 | 61.5 | |

| No | 77 | 38.5 | |

| Comfortable work environment | |||

| Yes | 68 | 34.0 | |

| No | 132 | 66.0 | |

| Equipment shortage | |||

| Yes | 133 | 66.5 | |

| No | 67 | 33.5 | |

| *Average perceived stress score | 27.68 (4.37) | ||

| Stress classification | |||

| Low (0–13) | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Moderate (14–26) | 60 | 30.0 | |

| High (27–40) | 140 | 70.0 | |

| Average psychological resilience score | 24.44 (4.74) | ||

| Levels of psychological resilience among ICU nurses | n | % | |

| Low 0–29 | 149 | 74.5 | |

| Moderate 30–36 | 51 | 25.5 | |

| High 37–40 | 0 | 0 |

2.2.2. Perceived Stress Scale 10 Items

Participants' perceived stress levels were measured via the Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10), developed by Cohen et al. [25]. It comprised 10 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 0 = never, 1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes. 3 = fairly often, to 4 = very often. Items 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 10 were negatively worded and assessed participants' perceived hopelessness. Items 4, 5, 7, and 8 were positively worded and assessed participants’ lack of self-efficacy. The total PSS-10 score was obtained by adding all items, with items 4, 5, 7, and 8 scored in reverse (4 to 0) and items 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 10 scored from 0 to 4 [25]. The total PSS-10 scores ranged from 0 to 40 points, with higher scores indicating a higher level of stress. Cronbach's alpha of the original scale was 0.78 [26] and was >0.70 in 12 studies [27]. The construct and discriminant validities of the PSS-10 were assessed through correlational analysis of anxiety, depression, helplessness, and disease activity [25].

2.2.3. The Connor-davidson Resilience Scale 10 (CD-RISC-10)

The CD-RISC-10 was a short version of the original CD-RISC-25 developed by Campbell-Sills and Stein [28]. It measured participants’ resilience to a stressful event. Participants reported their level of agreement with statements related to different aspects of resilience over the past 30 days. The scale comprised 10 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 0 = not true at all, 1 = rarely true, 2 = sometimes true, 3 = often true, to 4 = true nearly all the time. This scale comprised the following traits: flexibility, sense of self-efficacy, ability to regulate emotions, optimism, and cognitive focus/preserving attention under pressure [29]. The total scores ranged from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating better resilience. Cronbach’s alphas for the CD-RISC-10 and the original CD-RISC-25 were 0.85 [28] among 806 participants. and 0.89 [30], respectively.

2.3. Pilot Study

A pilot study was conducted to test the feasibility and practicality of the instruments used in this study. The author distributed 18 paper copies of the sociodemographic, PSS-10, and CD-RISC-10 questionnaires to ICU nurses working in the participating hospital, and these data were excluded from the main study. Cronbach’s alpha for the PSS-10 was α = 0.81, and that for the CD-RISC-10 was α = 0.82. The instruments also demonstrated acceptable test-retest reliability over a two-week interval for the same group, with Cronbach’s alpha for the PSS-10 being α = 0.82 and for the CD-RISC-10 being α = 0.81.

2.4. Ethical Approval

Various ethical concerns were addressed in this study. First, the research proposal was reviewed by the Scientific Committee at Al-Ahliyya Amman University to obtain approval to conduct the study (# MM 2/6-2024). Second, all participants were required to sign an informed consent form, witnessed by the researchers. Third, participants did not receive incentives for participation in the study. Participation was voluntary, and individuals could withdraw without penalty; withdrawal would not impact their current or future employment status. Fourth, the purpose of the study, benefits, and potential risks, such as time loss and emotional distress, were explained to the participants. Fifth, participants were given a list of experts they could contact for counseling support. Sixth, measures were taken to protect participants' confidentiality, privacy, and anonymity. For instance, pseudo-codes were used to avoid the use of personally identifiable details.

2.5. Data Analysis

Categorical data were expressed in frequencies and percentages, and scale data were expressed in mean and SD. Nominal and ordinal values were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Pearson’s correlation was used to identify the relationship between the variables. Furthermore, an independent t-test was used to explain the bivariate associations or mean differences in stress and resilience based on demographic data. Multiple linear regression was used to identify the significant predictors of perceived stress. Assumptions for the parametric tests regarding normal distribution, homogeneity of variance, and linearity were initially checked. The alpha level was set at 0.05. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 28.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

This study included 200 ICU nurses, with a mean age of 33.15 years (SD=5.23, range 23–51 years). Their average work experience in the ICU was 7.25 years (SD=3.38, range 1–20 years). The sample comprised 112 female nurses (56.0%) and 88 male nurses (44.0%). Regarding work environment distribution, most nurses (n=127, 65.5%) worked at AL-Bashir Hospital and Prince Hamza Hospital (n=61, 30.5%), while 12 nurses (6.0%) worked at AL-Nadeem Hospital. Furthermore, half were married (n=103, 50.0%) while 32 (16.0%) reported other marital statuses.

Regarding work shifts, 103 nurses (51.5%) followed an 8-hour shift system compared with 97 (48.5%) who followed a 16-hour shift system; furthermore, most nurses (n=123, 61.5%) reported working extra hours in the ICU. Concerning work environment, 66.0% (n=132) indicated that they worked in an uncomfortable environment, whereas only 34.0% (n=68) reported working in a comfortable work environment. Ultimately, 66.5% (n=133) acknowledged experiencing equipment shortages, whereas 33.5% (n=67) reported that they did not face such shortages in their work environment.

The overall mean score for perceived stress among the nurses was 27.68 out of 40 (SD= 4.37), which ranged from 14–37. According to the stress classification system, no nurses reported a low stress level; however, 30.0% (n=60) experienced moderate stress, and most (70.0%, n=140) experienced high stress.

The overall mean score for psychological resilience among the nurses was 24.44 out of 40 (SD= 4.74), which ranged from 13–36. According to the Psychological Resilience Classification System, most (n=149, 74.5%), one-quarter (n=51, 25.5%), and no nurses had low, moderate, and high psychological resilience, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the nurses’ sociodemographic characteristics.

3.2. Correlation between Perceived Stress and Psychological Resilience

Pearson’s product-moment correlation revealed a statistically significant, strong inverse relationship between perceived stress and psychological resilience (r r= -0.652, p < 0.001, N = 200), and 42.5% of the variance was explained by this association Table 2.

| Perceived stress | Psychological resilience |

|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation | -0.652 |

| P-value | <0.001 |

| N | 200 |

| R-squared | (-0.609)2 =0.425 |

3.3. Specific Stressors Contributing to Perceived Stress regarding Sociodemographic Characteristics

Bivariate analysis was performed to capture the association between nurses’ characteristics and perceived stress levels as a preliminary analysis prior to the multiple linear regression analysis. Age (r= 0.271) and experience (r= 0.306) had a significant positive relationship with perceived stress, p<0.001. Moreover, gender revealed a significant effect, t(198)=2.781, p= 0.006, indicating that female nurses (Mean= 28.43, SD= 3.81) had higher perceived stress scores than male nurses (Mean= 26.73, SD= 4.84). Marital status also had a significant effect (F(2, 197) =17.537, p <0.001). Scheffe’s post-hoc analysis revealed that single nurses (Mean= 28.91, SD= 3.00) and nurses with other marital statuses (Mean= 30.19, SD= 1.96) reported significantly higher perceived stress scores than married nurses (Mean= 26.04, SD= 5.02).

Furthermore, nurses who followed a 16-hour shift system (Mean= 29.73, SD= 2.38) reported significantly higher stress scores compared with those who followed an 8-hour shift system (Mean= 25.75, SD= 4.91; t(198)=7.234, p<0.001). Further, those who worked extra hours (Mean= 29.35, SD= 3.11) exhibited higher stress levels compared with those who did not (Mean= 25.01, SD= 4.76) t(198)=7.794, p<0.001.

Similarly, nurses who reported that their work environment was uncomfortable (Mean= 29.05, SD= 3.02) exhibited significantly higher stress scores compared with those who worked in a comfortable setting (Mean= 25.03, SD= 5.29; t(198)=6.833, p<0.001). ICU nurses who acknowledged experiencing equipment shortages (Mean= 28.75, SD= 3.35) reported significantly higher stress scores compared with those who did not face such shortages (Mean= 25.25, SD= 5.31), t(198)=5.202, p<0.001. Finally, hospital participants reported an insignificant impact on the perceived stress score p= 0.250, Table 3.

| Variables | Categories | N | Perceived stress | Test value | P-value | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | ||||||

| Age in years | 27.68 | 4.37 | 0.271 | <0.001r | 0.271 | ||

| Work experience in years | 27.68 | 4.37 | 0.306 | <0.001r | 0.306 | ||

| Gender | Males Females |

88 112 |

26.73 28.43 |

4.84 3.81 |

2.781 | 0.006 t | 0.396 |

| Participants’ work environment | AL Basheer hospital Prince Hamza hospital AL-Nadeem hospital |

127 61 12 |

27.87 27.69 25.67 |

4.02 4.88 4.94 |

1.397 | 0.250 F | 0.014 |

| Marital status | Married Single Others |

100a 68b 32c |

26.04 28.91 30.19 |

5.02 3.00 1.96 |

17.537 | <0.001F | 0.21 |

| Scheffe post hoc | |||||||

| A vs B A vs C B vs C |

<0.001 <0.001 0.340 |

||||||

| Work stressors | |||||||

| Shift work | 8 hours x 6 days 16 hours x 3 days |

103 97 |

25.75 29.73 |

4.91 2.38 |

7.234 | <0.001t | 1.02 |

| Participants work extra hours in the ICU | Yes No |

123 77 |

29.35 25.01 |

3.11 4.76 |

7.794 | <0.001t | 1.10 |

| Comfortable work environment | Yes No |

68 132 |

25.03 29.05 |

5.29 3.02 |

6.833 | <0.001t | 0.97 |

| Equipment shortage | Yes No |

133 67 |

28.75 25.55 |

3.35 5.31 |

5.202 | <0.001t | 0.73 |

3.4. Predicting Perceived Stress Score among ICU Nurses

To create an appropriate multiple linear regression model, variables with significant results in the bivariate analysis (nurses’ age, ICU experience, gender, marital status, type of shift work, working extra hours, working in a comfortable work environment, and equipment shortage) were entered into a forward multiple linear regression to predict the perceived stress score. This method begins with no predictors, and variables are gradually added one by one; predictors considered more influential are added first and remain in the final model. This selection method enhanced prediction accuracy, minimized overfitting, optimized classifier performance, and reduced multicollinearity.

Table 4 presents the final model. Working extra hours, working in a comfortable work environment, type of shift, and marital status (single and other) collectively explained 40.4% of the variance in perceived stress scores (Adjusted R2 = 0.404), F(5, 194) = 27.972, p < 0.001.

The strongest predictor was working extra hours (B = 2.80, t = 5.277, p < 0.001), indicating that nurses who worked extra hours had, on average, 2.80 units higher perceived stress scores compared with nurses who did not, with 8.35% of the variance explained exclusively by this factor.

The second strongest predictor was working in a comfortable work environment (B = 2.116, t = 3.783, p < 0.001), revealing that nurses who worked in an uncomfortable environment had, on average, 2.116 units higher perceived stress scores compared with those in a comfortable setting; this factor accounted for 4.28% of the variance.

Shift type ranked third, with nurses on a 16-hour shift system having, on average, 1.728 units higher perceived stress scores compared with nurses on an 8-hour shift system (B = 1.728, t = 3.086, p = 0.002), explaining 2.92% of the variance.

Marital status also had a significant impact. Nurses who were divorced or widowed (“other”) and single had, on average, 2.209 and 1.334 units higher perceived stress scores compared with married nurses, respectively (other: B = 2.209, t = 3.086, p = 0.002; single: B = 1.334, t = 2.381, p = 0.018); these factors explained 2.86% and 1.69% of the variance, respectively.

3.5. Prediction Accuracy Analysis

The Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) were used to evaluate the accuracy of multiple linear regression models. These metrics conveyed how far the predicted values were from the actual values (stress raw score).

Table 5 presents the results of the multiple regression analysis. The MAE prediction model predicted stress scores deviate by approximately 2.54 units from the actual values. However, the RMSE prediction error was approximately 3.31 units, which was considered a small prediction error. Additionally, the MAE and RMSE prediction models were lower than the MAE and RMSE of the baseline model, which indicated that the model performed better than estimating the average perceived stress score; furthermore, including predictors improved prediction accuracy. Hence, our model predicted that stress scores would deviate from the actual stress scores by 10.20% (MAPE=10.20%).

| Stressors Contributing to Perceived Stress Among ICU Nurses | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t-value | P-value | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | Unique Variance explained |

VIF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| Participants work extra hours in the ICU (Yes vs No) | 2.800 | 0.531 | 0.313 | 5.277 | <0.001 | 1.753 | 3.846 | 8.35 | 1.173 |

| Comfortable work environment (No vs Yes) | 2.116 | 0.559 | 0.230 | 3.783 | <0.001 | 1.013 | 3.219 | 4.28 | 1.235 |

| Shift work (16 vs 8 hours) |

1.728 | 0.554 | 0.198 | 3.119 | 0.002 | 0.635 | 2.821 | 2.92 | 1.350 |

| Marital status (Married) | Reference | ||||||||

| Marital status (Others) | 2.209 | 0.716 | 0.186 | 3.086 | 0.002 | 0.797 | 3.621 | 2.86 | 1.213 |

| Marital status (Single) | 1.334 | 0.560 | 0.145 | 2.381 | 0.018 | 0.229 | 2.439 | 1.69 | 1.240 |

| Models | MAE | RMSE | MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction model (model with predictors) | 2.54 | 3.31 | 10.20% |

| Baseline model/ Benchmark (stress mean score =27.68, SD=4.37, critical t value=1.97, N=200) |

3.50 | 4.35 | ---- |

, MAPE (10-20%) good accuracy.

, MAPE (10-20%) good accuracy.

The 95.0% Prediction Interval (PI) for individual nurses’ stress scores was constructed and between 19.05–36.31, which indicated that the regression model with included predictors predicted individual nurses’ stress scores within that range 95.0% of the time; this indicated that if a nurse was randomly selected, a stress score would likely fall within this interval and prediction interval extended 8.63 units above and below the mean prediction. (mean lower bound: mean upper bound =8.63).

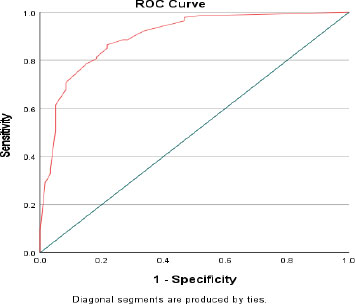

3.6. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Analysis

The ROC curve was derived from predicted values of significant predictors to demonstrate the sensitivity and specificity of these predictors in classifying high stress levels using a threshold of the original high stress score (≥27). The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.90, p<0.001, [95%CI 0.852–0.947], which indicated excellent diagnostic accuracy. Coordinates of the curve revealed that use of the aforementioned threshold value for high perceived stress in the model yielded a sensitivity of 85.0% and specificity of 78.3% (Fig. 1).

4. DISCUSSION

This study revealed the relationship between perceived stress and psychological resilience among nurses. Furthermore, the impact of demographic and work stressor variables on stress levels was explored. A statistically significant inverse relationship was observed between perceived stress and psychological resilience. These findings implied that the more resilient nurses became, the less they experienced stress at work.

Our findings of an inverse relationship between perceived stress and resilience levels were supported by previous literature. Saravanan et al. reported that ICU nurses exposed to prolonged stress experienced emotional exhaustion and burnout [31]. Furthermore, they implied that lack of resilience was inversely related to stress and burnout. Vahedian-Azimi et al. found that stress and burnout were associated with decreased emotional and physical well-being [32]. Moreover, they demonstrated that resilience was an important factor in promoting emotional and physical well-being, which could be negatively affected by high levels of stress and burnout.

Results revealed that age and work experience had positive and significant impacts on perceived stress. These findings implied that older and more experienced nurses reported higher levels of stress and aligned with those of Guttormson et al., who reported that nurses experienced moderate to high stress levels due to long hours of exposure to COVID-19 in 2020 [33]. They also implied that exposure was positively correlated with high stress levels. Healthcare personnel who worked during the pandemic reported high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, and the main characteristics linked to psychological distress were being male, married, and older than 40 years [34]. Thus, experienced and older nurses were more exposed to traumatic events, which resulted in their high perceived stress in this study.

Based on these findings, female nurses were more susceptible to perceiving stress levels compared with male nurses. Current literature has not addressed the possible reasons why women experience higher levels of stress compared with their male counterparts. Possible explanations could include work-life balance challenges. Future researchers should explore the possible reasons why female nurses experience higher stress levels than male nurses.

A significant relationship was observed between perceived stress and marital status. Single nurses and those divorced or widowed exhibited higher stress levels than married nurses. Fadillah et al. reported that inadequate time spent with family members owing to being busy may lead to higher stress levels among nurses [35]. However, in this study, single and divorced nurses experienced higher levels of stress. These findings implied that reduced stress levels among married nurses may be attributable to the presence of a strong family support system.

Workplace conditions also impacted nurses’ stress. Nurses who worked 16-hour shifts reported higher stress levels compared with those who worked eight-hour shifts. Based on the regression analysis, extra hours were the strongest predictor of perceived stress. These results were consistent with those of Mousazadeh et al., who reported that increased workload raised stress levels and resulted in job dissatisfaction [36]. Therefore, ICU nurses who worked 16-hour shifts or extra hours perceived higher stress, likely due to work overload. Consequently, these nurses were more likely to be dissatisfied with their jobs due to elevated stress levels.

Nurses who reported that their work environment was uncomfortable also experienced higher stress levels. Furthermore, nurses who reported equipment shortages reported increased stress. Although we did not ask participants which equipment was lacking, nurses may have perceived stress because they felt their health and patient safety were at risk, were unable to provide optimal care, and had to constantly improvise. This is consistent with a previous study [33], which linked the absence or lack of personal protective equipment to mental health issues.

This study emphasized stress among ICU nurses, an issue that demands the attention of hospital management. The potential of sociodemographic variables to predict perceived stress was further explored. Variables that showed significant results in the bivariate analysis (age, gender, experience in ICU, marital status, work shift, working extra hours, comfortable work environment, and equipment availability) aligned with those reported in other studies [37, 38]. This study identified the sociodemographic variables that predicted perceived stress. Working extra hours, comfortable work environment, work shift, and single or other marital status collectively contributed 40.4% to the overall perceived stress score, suggesting that these variables significantly impacted the differences observed in the dataset, while the remaining 59.6% of variability was explained by other variables not considered in the analysis. Specifically, perceived stress from working extra hours, a comfortable work environment, being divorced or widowed, and being single accounted for an additional 8.35%, 4.28%, 2.86%, and 1.69% of the variance, respectively. These variables emerged as predictors of perceived stress and could potentially be mitigated through resilience.

ROC analysis was used to evaluate the accuracy of the multiple linear regression models and the performance of the perceived stress scale. The multiple linear regression model predicted perceived stress scores 95.0% of the time, with up to 85.0% sensitivity and 78.0% specificity. Hence, it efficiently predicted perceived stress. An area under the curve (AUC) of 0.90 indicated excellent diagnostic accuracy. Hosmer and Lemeshow’s classification of AUC of 0.5, 0.7–0.8, 0.8–0.9, and >0.9 was considered no discrimination, acceptable, excellent, and outstanding, respectively [39]. This suggested a 90% chance that perceived stress would correctly discriminate between individuals who were stressed and those who were not stressed.

5. LIMITATIONS

Despite providing significant insights into the relationship between stress, resilience, and contributing factors, this study has some limitations and gaps. First, data were self-reported, which may have introduced response biases, as participants could have misreported their stress levels. Second, the causal mechanisms underlying the relationship between demographics and work environment conditions were not extensively evaluated. Third, this study was conducted in a single setting, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other contexts.

Furthermore, two gaps were identified. First, there was a lack of qualitative data to understand how nurses perceived and coped with stress. Second, the study did not provide a conclusive explanation for why women experienced higher levels of stress. Additionally, as a cross-sectional study, it cannot establish causality and is susceptible to various biases, including sample selection bias. Further analysis is required to clarify the association between gender and higher stress levels among nurses.

Lastly, this study used convenience sampling. The disadvantage of using a convenience sample is that it may not reflect the larger population, undermining the validity and generalizability of the results. The first researcher was present in the room during data collection and ensured that all items in the questionnaires were marked, which would be considered biased.

6. IMPLICATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Perceived stress and resilience in nursing should be assessed to identify areas for improvement. Limiting excessive working hours and adequate staffing should be implemented in hospital settings to reduce perceived stress levels. Additionally, improving working conditions, such as providing adequate resources, could help reduce stress among nurses.

Future studies should conduct longitudinal studies to determine the impact of stress reduction tailored towards promoting resilience on stress levels. In addition, qualitative methods, such as interviews and focus groups, may be useful to determine nurses’ experiences and how they cope with stress. Qualitative analysis may also help establish the underlying reasons why certain factors, such as gender, influence stress levels.

CONCLUSION

This study explored the relationship between perceived stress, resilience, and work environmental factors among nurses. Results revealed that perceived stress levels were high and psychological resilience was low. Perceived stress was inversely correlated with psychological resilience. Factors such as being older, having more workplace experience, being female, divorced/widowed, working 16-hour shifts, working extra hours, being in an uncomfortable environment, and facing a shortage of equipment were significantly associated with higher stress levels. In regression analysis, nurses’ age, workplace experience, and facing a shortage of equipment had no significant effect on perceived stress scores. Future studies aimed at enhancing nursing resilience and well-being are recommended.

Although this study provides valuable insights into perceived stress and resilience, certain limitations remain, including the reliance on self-reported data and a sample confined to ICUs in three hospitals. Future studies should consider additional factors affecting nurses’ perceptions of stress, such as sleep patterns, dietary habits, physical activity, and caregiving responsibilities for infants or toddlers at home. Moreover, research should include other medical professionals working in ICUs, not only registered nurses with bachelor’s degrees.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contributions to this research project as follows. M.D. and E.A.: Were responsible for the study conception and design; M.D.: Conducted the data collection, while; M.D. and A.E.: Carried out the data analysis and drafted the manuscript. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ICU | = Intensive Care Unit |

| PSS-10 | = Perceived Stress Scale-10 |

| CD-RISC-10 | = Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was reviewed and approved by the Scientific Committee of Al-Ahliyya Amman University (IRB # MM 2/6-2024) in June 2024.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author [EA] on request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all ICU nurses who participated in the study.