All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Educational Technology on Neuropathies for People with Diabetes Mellitus: An Evaluation Study

Abstract

Introduction

The provision of care to patients with Diabetes and Neuropathy must be based on health education. Educational technologies are facilitating means in this context, and after their construction, the evaluation stage is essential for improvement and analysis of the educational product. To evaluate, through the judgment of specialists and the target audience, an educational technology in booklet format on Neuropathies for people with Diabetes Mellitus.

Methods

This educational technology evaluation study, focused on interface in methodological development, employed a quantitative approach and was divided into two stages: Content and Appearance Evaluation, carried out in 2024, and Semantic Evaluation, carried out in 2025. Fifteen health specialists, nine experts in the didactic-illustrative field, and eighteen patients with diabetic neuropathies from a specialty center participated. For data collection, questionnaires were used and interpreted through the Content Index, the Summative Score of the adapted Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) instrument, and the Semantic Index.

Results

The overall Content Index was 0.91, and the Appearance Evaluation obtained a score higher than 10 points in SAM. The booklet was improved following the specialists’ suggestions for version II. The overall Semantic Index was 0.98. The suggestions from the target audience were used to improve the booklet for the final version.

Discussion

Moreover, the management of Diabetes Mellitus is carried out daily and continuously, combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures such as a balanced diet, physical exercise, and periodic personalized clinical care according to the patient’s individual needs. In this way, health communication provided through educational technologies can contribute to preventing or delaying the progression of comorbidities caused by Diabetes, such as Neuropathies.

Conclusion

The booklet was evaluated for use as an educational technology for individuals with diabetes mellitus.

1. INTRODUCTION

Diabetic neuropathies can be classified into two major categories: diffuse, encompassing sensorimotor polyneuropathy and autonomic neuropathy, and focal, represented by diabetic mononeuropathy and radiculoneuropathy [1-3].

Neuropathy is also considered the most prevalent chronic complication of diabetes, particularly in the northern region of Brazil, due to the influence of dietary habits characterized by carbohydrate-rich diets. Such habits represent a significant risk factor for hospital admissions, given the physiological changes involving the autonomic nervous system and the emergence of small lesions on the lower limb extremities. If these lesions are not detected and treated in a timely manner, they may progress to plantar ulcers and, in severe cases, result in limb amputation in individuals affected by this complication [4].Considering these factors, nursing care plans for individuals with neuropathies should be based on the pillars of health promotion and the prevention of complications, with the goal of strengthening self-care. In this context, Health Educational Technologies (HETs) represent an exceptional and accessible means of establishing a connection with patients, ranging from the development of informational folders and booklets to the creation of serious games, all aimed at delivering information in a more assertive and engaging manner [5].

In this regard, booklets, understood as educational technologies, serve as a widely used tool for knowledge exchange in the healthcare field, as they are easily accessible in both printed and digital formats. This is especially relevant in contemporary times, with the support of Artificial Intelligence (AI), which has emerged as an innovative tool capable of supporting the creation and improvement of educational technologies, enabling the development of more accessible and engaging materials. However, although AI represents a modern and promising resource, it does not replace the need for a thorough evaluation by subject-matter experts and the target audience for whom the technology is intended. These steps are essential to ensure the quality, appropriateness, and effectiveness of educational health technologies [6, 7].

In 2023, an educational technology was developed in three stages: (1) an integrative literature review (ILR), (2) field research through semi-structured interviews, and (3) technological production. Data obtained from the interviews were analyzed and compared with the ILR findings, resulting in the creation of a 10-page booklet entitled Shall We Talk About Diabetic Neuropathies?. The booklet was designed for primary and secondary health care in outpatient settings and addressed topics related to neuropathies, including types of neuropathy, signs and symptoms, skin and extremity care for patients with diabetes, appropriate clinical management, and prevention. The visual communication of the booklet was organized by a graphic design professional using the Canva® platform, without the use of artificial intelligence [8].

Health education products, such as booklets, once developed, benefit from being subjected to structured evaluation processes that assess their attributes, identify limitations, and determine areas for improvement. Such evaluations facilitate optimization, enhance feasibility, and reaffirm the accuracy of the tool, ensuring targeted and relevant content [9]. From this perspective, the aim of the present study was to evaluate, through expert review and feedback from the target audience, an educational technology in the form of a booklet on neuropathies for individuals with diabetes mellitus.

2. MATERIALS & METHODS

2.1. Study Design

This is an evaluation study of an educational technology in booklet format, with an interface in methodological development research and a quantitative approach [10, 11]. The methodological process was divided into two stages: (1) content and appearance evaluation, followed by the refinement of the technology to produce Version II, and (2) semantic evaluation and the development of Version III of the technology.

2.2. Content Evaluation and Appearance Evaluation

2.2.1. Setting and Participants of the Content Appearance Evaluation

The first stage, which involved evaluating content and appearance, was conducted virtually. The technology and the data collection instrument were sent to participants via Google Forms.

For the content evaluation, the study included reviewers from the health field to assess the technical and scientific dimensions. This group consisted of 15 participants, including nurses, physicians, nutritionists, and one physical educator; these professionals had expertise and/or provided care to patients with diabetes [10].

For the appearance evaluation, nine reviewers participated, including graphic design professionals, social communication professionals, and a pedagogue. For this evaluation, a non-probabilistic sampling strategy was used, specifically the network sampling or snowball technique [12].

Inclusion criteria for the content evaluation required health experts to have at least three years of clinical-care experience with patients diagnosed with diabetes, publications in journals and/or events on diabetes and/or neuropathies, and/or specialization (lato sensu or stricto sensu) in neurology, endocrinology, or family health, as well as membership in a scientific society related to the thematic area [13].

Professionals participating in the appearance evaluation were required to have at least two years of professional experience with the booklet format as an educational technology, publications in journals and/or events on educational technologies, and/or registered and/or applied work using the booklet format, and specialization (lato sensu or stricto sensu) in their professional field [13].

Exclusion criteria for both content and appearance evaluators included agreeing to participate but failing to return the completed evaluation within 30 days, despite prior communication attempts.

2.2.2. Data Collection for Content and Appearance Evaluation

Data collection, involving content and appearance evaluation panels, took place simultaneously over a three-month period, from April 2024 to June 2024. After project approval by the Research Ethics Committee and considering the inclusion criteria, evaluators were identified through a search of curricula on the Brazilian Lattes Platform, which records the academic and professional history of Brazilian students and researchers [14]. The “subject search” tool on the Lattes Platform was used with keywords such as Diabetes, Diabetic Neuropathies, Technology Evaluation, Health Education, and Booklet for health specialists. For specialists in the didactic-illustrative dimension, keywords included Design, Visual Communication, Pedagogy, and Booklet.

Following the searches, contact with specialists was made via email when available on the Lattes Platform, or through the platform’s “Contact” option. An invitation letter was sent to 54 health specialists and 37 didactic-illustrative specialists, introducing the researcher, explaining the study’s purpose and objectives, and clarifying the participation process in the expert panel. Within four days, 19 content evaluators and four appearance evaluators responded to the invitation, confirming their participation or providing an active email address for communication.

Those who expressed interest in participating, after reading the invitation letter, received an Informed Consent Form (ICF) tailored for either health specialists or didactic-illustrative specialists via email. The signed and returned ICF was required within seven consecutive days. Notably, along with the signed ICFs from didactic-illustrative specialists, three appearance evaluators suggested one additional qualified participant each, and one evaluator suggested two additional participants, thus following the snowball sampling concept [12]. All suggested appearance evaluators agreed to participate in the study.

After receiving the duly signed ICF, an email containing a Google Forms link was sent. By clicking the link, evaluators accessed images of the booklet on Diabetic Neuropathies (with a watermark) and the evaluation instrument, which differed in content and appearance for content and appearance specialists. The instrument was completed directly in Google Forms, and responses were sent to the researcher within a maximum of 30 consecutive days.

It is worth noting that seven days before the 30-day deadline, all participants who had not yet completed their evaluation received a reminder email with the final submission date. This proved essential for receiving most evaluations within the established timeframe. However, four health specialists did not submit their evaluations and were excluded from the study, while all appearance evaluators submitted their assessments within the deadline.

The instrument used for content evaluation consisted of sections addressing the purpose, motivation, and adaptation of the technological product. The instrument used for appearance evaluation focused on design and marketing aspects to assess the suitability of educational materials, based on the Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) scale, which was adapted to 13 items [14].

2.2.3. Data Analysis for Content and Appearance Evaluation

For interpreting the data from the content evaluation, the Content Validity Index (CVI) was used, with an overall CVI threshold of 80% (0.80). The index was calculated by dividing the number of items rated “1” or “2” by the total number of responses, then multiplying the result by 100 to obtain a percentage [15]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was also calculated to assess the reliability of the instrument [16].

The analysis of appearance evaluation data was based on the interpretation of the 13-item SAM scale, using the total points obtained for each question. To be considered adequate, the technology needed to achieve a score of equal to or greater than 10 [14].

2.2.4. Adjustments to the Educational Booklet After Content and Appearance Evaluation

Adjustments were made based on suggestions from the panel of experts in both the technical-scientific and didactic-illustrative areas. Changes included modifications to character depiction and color schemes, as well as improvements in the information provided.

2.3. Semantic Evaluation

2.3.1. Setting and Participants of the Semantic Evaluation

The semantic evaluation took place at a Medical Specialties Center, using a non-probabilistic convenience sampling method based on data from the center’s appointment scheduling system over a two-month period. The selection considered participants with different educational backgrounds (elementary, secondary, and higher education). Nineteen appointments were scheduled for patients with this profile during the two-month period, according to information provided by the center’s head nurse. Considering a 5% sampling error, eighteen patients with diabetic neuropathies participated in the study.

Participants included men and women with complete or incomplete elementary, secondary, or higher education, diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus and neuropathies, and undergoing follow-up at the medical specialties center. Exclusion criteria included patients under 18 years of age, illiterate individuals, and those with cognitive difficulties or impairments preventing comprehension of the research questions and documents.

2.3.2. Data Collection for the Semantic Evaluation

Data collection took place from December 2024 to January 2025. While in the waiting room for their routine appointments, patients were approached by the researcher. Those who agreed to participate were taken to a private room after their consultation, where the researcher read and explained the two copies of the Informed Consent Form, which were then signed.

The semantic evaluation instrument was divided into two parts: the first contained identification code, age, and gender; the second included completion instructions and five blocks of questions.

2.3.3. Data Analysis for the Semantic Evaluation

To interpret the evaluation instrument responses from the target audience, the Semantic Index (SI) was calculated, considering the proportion of participants in agreement regarding the instrument's aspects. In this study, a minimum SI threshold of 80% (0.80) was established. The calculation was based on the scores provided by evaluators using a four-point scale ranging from 1 to 4, with the SI equal to the number of responses rated 1 or 2 divided by the total number of responses [15]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was also calculated at this stage [16].

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This theoretical framework was registered on the Plataforma Brasil and submitted to the Research Ethics Committee of the State University of Pará, Magalhães Barata School of Nursing. It was approved in April 2024 under approval number 6.737.045 / CAAE: 78331224.5.0000.5170.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characterization of the Specialists in Content and Appearance Evaluation

The majority of the participants in the Content evaluation were female (n =12), with an average age between 34 and 44 years. It was also evident that most of the evaluators resided in the state of Pará (n =11). The health professionals who participated were, for the most part, nurses, totaling (n =8); regarding their professional activity, most worked in the teaching field (n =8). As for academic qualifications, most (n = 8) reported holding a Master’s degree.

Regarding the characterization of the specialists in the appearance evaluation, females predominated (n = 5), and the most prevalent age range among participants was 34 to 44 years (n = 5). Regarding the state of residence, most participants lived in Pará (n = 5). Among the panel of specialists for the appearance evaluation, most had a degree in graphic design (n = 5).

3.2. Content Evaluation

In the present study, the specialists’ responses were organized according to clarity and relevance, structure and presentation, and relevance of the technology. The Content Validity Index (CVI) and its respective individual percentage by block, as well as the total CVI and Cronbach’s alpha, were calculated, as shown in Table 1.

| Items | Total Number of Participants Score (n=15) | CVI | % | Cronbach`s Alpha | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1- Clarity and Relevance | SA | A | PA | D | - | - | - |

| 1.1 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0,86 | 86% | 0,922 |

| 1.2 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,929 |

| 1.3 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0,86 | 86% | 0,924 |

| 1.4 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0,93 | 93% | 0,922 |

| 1.5 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0,93 | 93% | 0,927 |

| Block Result | 50 | 19 | 6 | 0 | 0,92 | 92% | - |

| % of total responses per block | 66,7% | 25,3% | 8% | 0% | - | - | - |

| Block 2- Structure and Presentation | SA | A | PA | D | - | - | - |

| 2.1 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0,86 | 86% | 0,923 |

| 2.2 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0,86 | 86% | 0,921 |

| 2.3 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0,93 | 93% | 0,924 |

| 2.4 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0,80 | 80% | 0,922 |

| 2.5 | 11 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,929 |

| 2.6 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,927 |

| 2.7 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 2 | 0,80 | 80% | 0,921 |

| 2.8 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,921 |

| 2.9 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 0,73 | 73% | 0,921 |

| 2.10 | 1 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0,86 | 86% | 0,924 |

| 2.11 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,927 |

| Block Result | 77 | 71 | 11 | 6 | 0,89 | 89% | - |

| % of total responses per block | 46,6% | 43,0% | 6,7% | 3,3% | - | - | - |

| Block 3-Relevance | SA | A | PA | D | - | - | - |

| 3.1 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0,93 | 93% | 0,925 |

| 3.2 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| 3.3 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,927 |

| 3.4 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0,86 | 86% | 0,925 |

| 3.5 | 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,927 |

| Block Result | 57 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0,96 | 96% | - |

| % of total responses per block | 76% | 20% | 4% | 0% | - | - | - |

| Overall Content Index | - | - | - | - | 0,91 | 91% | - |

Note: Legend: CVI: Content Validity Index; SA: Strongly Agree; A: Agree; PA: Partially Agree; D: Disagree.

In Block 1, corresponding to the evaluation of the clarity and relevance of the booklet, most responses were “Strongly Agree,” with 50 responses (66.7%), and “Agree,” with 19 responses (25.3%). The total CVI for the first block was 0.92 (92%), a value above the threshold proposed to consider the technology valid (0.80 or 80%). The highest item CVI in the first block was 1.00, and the lowest was 0.86. The highest Cronbach’s alpha calculated per item was 0.929, and the lowest was 0.922.

In Block 2, the structure and presentation were evaluated. There were 77 items marked as “Strongly Agree” (46.67%) and 71 as “Agree” (43.03%). The total CVI was 0.89 (89%). The highest item CVI in the second block was 1.00, and the lowest was 0.73, which is below the established threshold for technology evaluation (0.80 or 80%). Therefore, this item was adjusted according to the specialists’ suggestions. This single item did not compromise the booklet evaluation process since the overall CVI for the block exceeded the methodological threshold (0.80 or 80%). The highest Cronbach’s alpha calculated per item was 0.929, and the lowest was 0.921. In Block 2, item 2.9 (“The size of the title and topics is appropriate”) was the only item that did not reach an individual CVI of 0.80, achieving only 0.73. However, since the block’s overall CVI (0.89) and Cronbach’s alpha were satisfactory, the item was improved, and the technology was considered valid.

In Block 3, which is responsible for evaluating the relevance of the booklet, 57 items were marked as “Strongly Agree” (76%), and 15 as “Agree” (20%). The total CVI for the block was 0.96 (96%), representing the highest block CVI in the content evaluation. The highest item CVI in Block 3 was 1.00, and the lowest was 0.86. The highest Cronbach’s alpha per item was 0.930, and the lowest was 0.925. Furthermore, the total CVI of the booklet evaluation by specialists was 0.91 (91%), a value above the expected and proposed threshold in the initial methodology.

3.2.1. Adjustments to the Booklet According to the Content Evaluators’ Suggestions

The suggestions from the content specialists were taken into consideration in composing version II of the educational booklet. Therefore, the font used in the booklet was standardized and increased in size, and a short text about Diabetes Mellitus was added before the section on Neuropathies. In addition, the explanation of Diabetic Neuropathies was better organized into two main categories (Diffuse and Focal).

3.3. Appearance Evaluation

During the appearance evaluation, the invited panel of specialists analyzed the appropriateness of the technology regarding its content (items 1.1 to 1.3), language (items 2.1 to 2.3), graphic illustrations (items 3.1 and 3.2), motivation (items 4.1 to 4.3), and cultural appropriateness (items 5.1 and 5.2). At the end, the scores assigned to each of the thirteen items were summed to obtain each evaluator’s total individual score. The specialists evaluated the technology using a three-point scale, assigning scores of 2, 1, or 0 (2 – Adequate; 1 – Partially Adequate; 0 – Inadequate). Table 2 shows the total score sum.

| Evaluator | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 5.1 | 5.2 | SAM Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 25 |

| 2. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 25 |

| 3. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 26 |

| 4. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 22 |

| 5. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 26 |

| 6. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 22 |

| 7. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 25 |

| 8. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 23 |

| 9. | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 21 |

Source: Research data, 2024.

Legend: SAM score.

Regarding the content evaluation (items 1.1 to 1.3), all three items in this category were rated as Adequate. As for the language used in the booklet (items 2.1 to 2.3), a single evaluator rated item 2.3 (“The vocabulary uses common words”) as Partially Adequate. Regarding graphic illustrations (items 3.1 and 3.2), item 3.1 received 5 ratings of Partially Adequate, while item 3.2 received 4 ratings of Partially Adequate.

As for motivation (items 4.1 to 4.3), item 4.1 (“There is interaction between the text and/or images and the reader, encouraging problem-solving, making choices, and/or demonstrating skills”) received 4 ratings of Partially Adequate. Concerning cultural appropriateness (items 5.1 and 5.2), item 5.2 (“Presents culturally appropriate images and examples”) received 5 ratings of Partially Adequate.

3.3.1. Adjustments to the Booklet According to the Appearance Evaluators’ Suggestions

Following the feedback from the appearance specialists, the booklet was improved regarding its graphic elements, with changes mainly in the characters’ illustrations to better connect with the target audience.

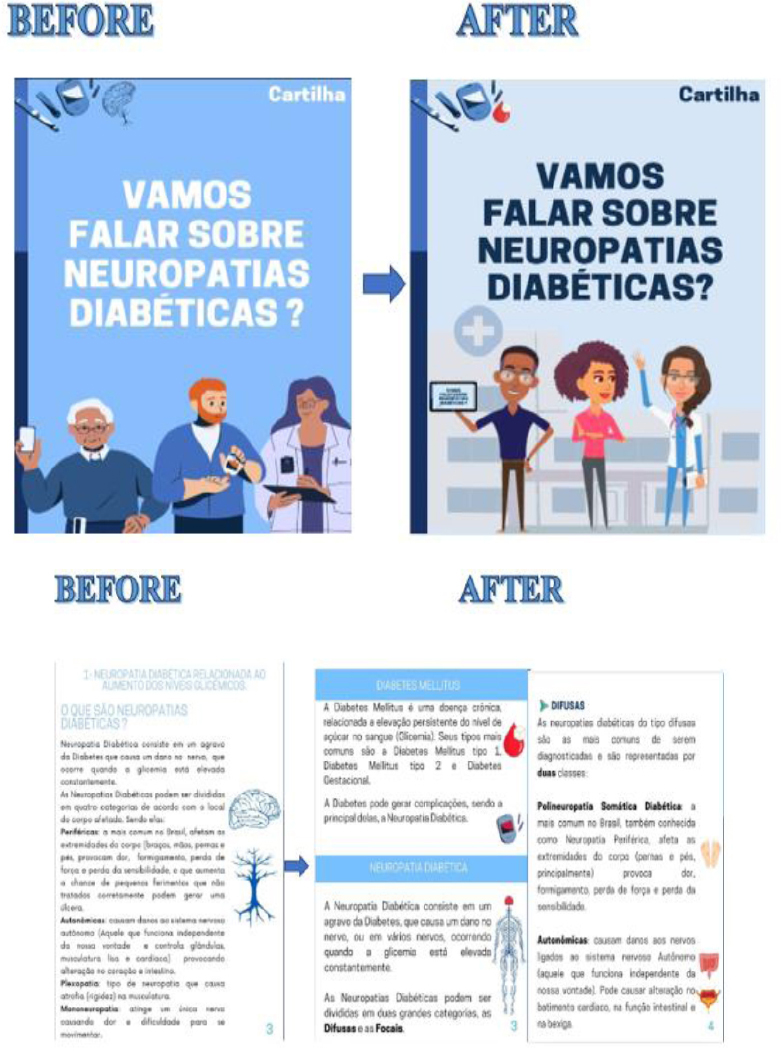

It is essential to note that, following the content and appearance evaluations, the educational booklet prioritized the increase and standardization of font size. The characters throughout the booklet were modified, and the presentation and table of contents were updated. Some figures and content were added, while others were refined. The second version of the educational technology contains 18 pages. The shades of blue were maintained, but on some pages, the blue tones were altered to increase contrast with the new figures and text. A before-and-after view of the booklet can be seen below in Fig. (1).

3.4. Characterization of the Experts in the Semantic Evaluation

Regarding the characterization of the participants in the semantic validation (n = 12), they were all female, representing the majority of participants. The predominant age group was 60 years and older (n=9) among the evaluators. As for educational level, (n=9) reported having completed elementary school, and regarding profession/occupation, (n=7) stated they were retired or pensioners. Concerning the clinical condition, 16 patients (n=16) had a diagnosis of type II DM, representing the largest portion of evaluators. Regarding the diagnosis of neuropathies, 13 patients (n=13) who evaluated the booklet reported receiving this diagnosis between 6 and 9 years ago. The most prevalent type of neuropathy among the participants was Peripheral Neuropathy (n=15).

Before and after the booklet layout. Belém, Pará, Brazil, 2024.

3.5. Semantic Evaluation

Semantic evaluation is an essential process that involves the target audience of the technology. In this study, responses from patients with diabetes/neuropathy were organized according to the following criteria: objective, organization, writing style, appearance, and motivation. The individual Semantic Index (SI) was also calculated, by block and total, with its corresponding percentage and Cronbach’s alpha, as presented in Table 3.

| Items |

Total Number of Participants Score (n=18) |

SI | % | Cronbach`s Alpha | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1- Objective | SA | A | PA | D | - | - | - |

| 1.1 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,927 |

| 1.2 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,927 |

| 1.3 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,927 |

| Block Result | 48 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | - |

| % of total responses per block | 88,9% | 11,1% | 0% | 0% | - | - | - |

| Block 2- Organization | SA | A | PA | D | - | - | - |

| 2.1 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| 2.2 | 14 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0,94 | 94% | 0,925 |

| 2.3 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,927 |

| 2.4 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| 2.5 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0,83 | 83% | 0,921 |

| 2.6 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| 2.7 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| Block Result | 113 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0,96 | 96% | - |

| % of total responses per block | 89,7% | 7,1% | 3,2% | 0% | - | - | - |

| Block 3- writing style | SA | A | PA | D | - | - | - |

| 3.1 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,927 |

| 3.2 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| 3.3 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0,94 | 94% | 0,925 |

| 3.4 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| 3.5 | 17 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,927 |

| 3.6 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0,94 | 94% | 0,925 |

| Block Result | 101 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0,98 | 98% | - |

| % of total responses per block | 93,5% | 4,6% | 1,9% | - | - | - | - |

| Block 4-Appearance | SA | A | PA | D | - | - | - |

| 4.1 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| 4.2 | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,927 |

| 4.3 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| 4.4 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| Block Result | 69 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | - |

| % of total responses per block | 95,8% | 4,2% | 0% | 0% | - | - | - |

| Block 5- Motivation | SA | A | PA | D | - | - | - |

| 5.1 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0,94 | 94% | 0,925 |

| 5.2 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,927 |

| 5.3 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| 5.4 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| 5.5 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| 5.6 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100% | 0,930 |

| Block Result | 103 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0,99 | 99% | - |

| % of total responses per block | 95,3% | 3,7% | 1,0% | 0% | - | - | - |

| Overall Semantic Index | - | - | - | - | 0,98 | - | - |

Note: Legend: SI: Semantic Index; SA: Strongly Agree; A: Agree; PA: Partially Agree; D: Disagree.

In Block 1, corresponding to the evaluation of the booklet’s objective by the target audience, responses were concentrated in the “Strongly Agree” category with 48 responses (88.9%) and “Agree” with 6 responses (11.1%). The total IS for the first block was 1.00 (100%), a value above the threshold proposed for considering the technology valid, 0.80 (80%). Therefore, all items in the first block obtained an IS of 1.00 (100%). Cronbach’s alpha for the lowest and highest item scores was equal at 0.927.

In Block 2, the booklet’s organization was evaluated, with 113 items marked as “Strongly Agree” (89.7%) and 9 as “Agree” (7.1%). The total IS corresponding to Block 2 was 0.96 (96%). The highest IS per item in the second block was 1.00 and the lowest was 0.83. The highest Cronbach’s alpha calculated per item was 0.930, while the lowest was 0.921.

In Block 3, the writing style was assessed. There were 101 items marked as “Strongly Agree” (93.5%) and 5 as “Agree” (4.6%). The total IS corresponding to Block 3 was 0.98 (98%). The highest IS per item in the third block was 1.00, and the lowest was 0.94. The highest Cronbach’s alpha calculated per item was 0.930, and the lowest was 0.925.

In Block 4, corresponding to the evaluation of the booklet’s Appearance by the target audience, responses were concentrated in the “Strongly Agree” category with 69 responses (95.8%) and “Agree” with 3 responses (4.2%). The total IS for the fourth block was 1.00 (100%). Thus, all items in the fourth block obtained an IS of 1.00 (100%). The highest Cronbach’s alpha calculated per item was 0.930 and the lowest was 0.927.

In Block 5, the evaluation focused on the Motivation that the booklet could offer to the target audience. There were 103 items marked as “Strongly Agree” (95.3%) and 4 as “Agree” (3.7%). The total IS corresponding to Block 5 was 0.99 (99%). The highest IS per item in the fifth block was 1.00, and the lowest was 0.94. The highest Cronbach’s alpha value was 0.930, and the lowest per item was 0.925. At this stage, the semantic evaluators, coded as (SE), made the following comments confirming the importance of the educational booklet on Neuropathy:

SE5- “I wish I had read and understood these things better back at the beginning, when I found out I had Diabetes. Now I try to stay informed because I have a foot problem.”

SE4- “The booklet is important. I myself didn’t know about cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, which is what the doctor said I had, until one day I ended up in the hospital.”

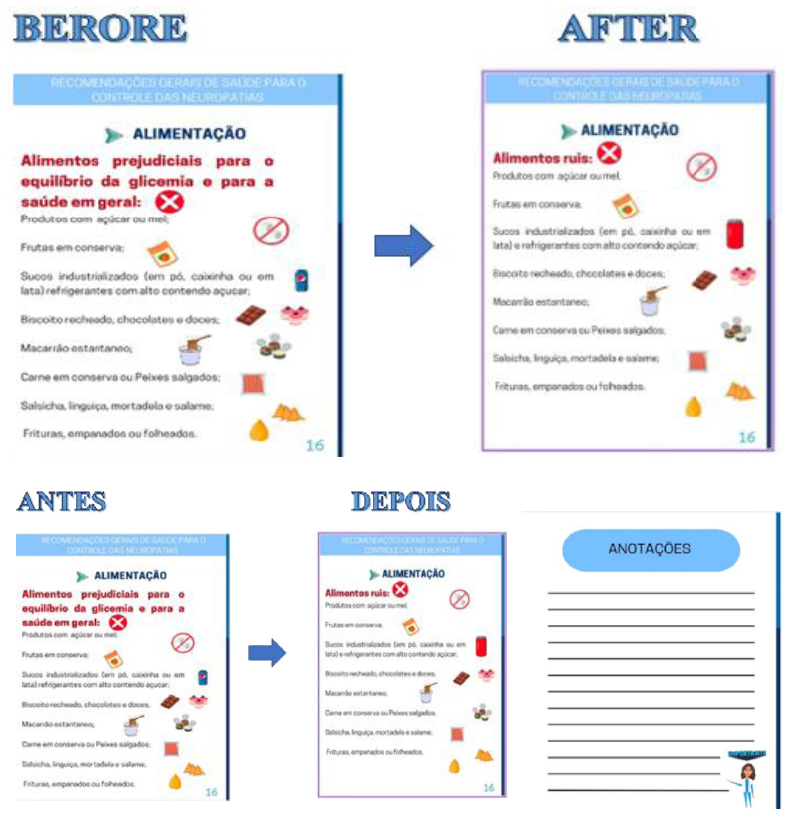

SE1- “The information is good, I didn’t find it hard to read. Just here, where it says ‘foods harmful to the balance of blood glucose and to overall health,’ it’s better to put just ‘harmful (bad) foods,’ so it’s easier for everyone to understand that, even if it’s tasty, it’s not good for your health.”

SE18- “I found the colors beautiful, the images relate to the text, and some things remind me of the food from our region, here in Belém.”

3.5.1. Adjustments to the Booklet based on Suggestions from the Target Audience

After the semantic evaluation, the suggestions offered by patients with Diabetic Neuropathies were considered and accepted. Consequently, a title in the nutrition section was changed from “foods harmful to the balance of blood glucose and to overall health” to “bad foods,” making the title more objective and easier to understand. Additionally, two pages were added to the technology for noting down pertinent and relevant information, as shown below in Fig. (2).

At the end of the semantic evaluation, the booklet was improved to its third and current version, entitled “Shall We Talk About Diabetic Neuropathies”?, consisting of 22 pages in shades of blue. The booklet was registered with the Brazilian Book Chamber and obtained the ISBN: No. 978-65-01-36587-9.

Before and after the booklet, following the semantic evaluation. Belém, Pará, Brazil, 2024.

4. DISCUSSION

Currently, Diabetes Mellitus is considered the most prevalent chronic non-communicable disease worldwide, being responsible for one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality through progressive complications such as neuropathies, grouped into two major categories: Diffuse and Focal [1, 17].

Regarding Neuropathies, they are a progressive comorbidity with the highest prevalence in type II diabetes mellitus, a fact that converges with the data found in this study. Moreover, neuropathies are generally diagnosed between five and ten years after the diagnosis of diabetes is established. However, this comorbidity can be present even in the stage preceding DM (Prediabetes), and its clinical signs and symptoms can negatively impact quality of life, being considered a clinical stressor for patients, hindering activities that were once simple to perform at home and in the workplace [18, 19].

In Brazil, the most common form of Neuropathy is Diabetic Somatic Polyneuropathy, which is characterized by neuropathic pain and paresthesia. Autonomic neuropathy, although less common, is responsible for significant problems in the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems, which increases the risk of hospital admissions. The diagnosis of Diabetes and Neuropathies has been increasing, especially in the South and Southeast regions of the country, also due to the pre-existence of other comorbidities such as obesity and hypertension. In regions such as the North and Northeast, the prevalence of Diabetes and Neuropathies, which was previously considered lower compared to other regions of Brazil, is currently expanding. This may indicate that the process of metropolitan growth and changes in eating habits are altering the epidemiological profile, especially in urban centers in these areas [20, 21].

The “diabetic foot” is one of the most well-known comorbidities of Diabetes Mellitus. It is considered one of the most common complications to be diagnosed and found in patients, being associated with different stages of neuronal impairment. Despite advances in the clinical management of this condition, diabetic foot care remains a significant challenge in the healthcare field, with information on the prevention and control of this comorbidity being a key pillar in reducing the problem [22].

Moreover, the management of diabetes mellitus is carried out daily and continuously, combining pharmacological and non-pharmacological measures, such as a balanced diet, physical exercise, and periodic, personalized clinical care tailored to the patient’s individual needs. In this way, health communication provided through educational technologies can contribute to preventing or delaying the progression of comorbidities caused by diabetes, such as neuropathies [23, 24].

From this perspective, it is essential to implement coordinated measures aimed at improving healthcare for patients with diabetes and neuropathies, both in the present and in future action plans. Health education initiatives constitute strategic measures for the prevention and control of neuropathies, especially for nurses, who maintain extensive contact with patients in their daily work. Furthermore, educational measures fall within the competencies and skills of nursing and are considered one of the main responsibilities of the profession. Among the forms of health education, educational technologies are a playful and effective way to enhance learning [24].

Addressing the importance of health education in the context of Diabetic neuropathies, a Brazilian study described the development and evaluation of an educational booklet on this topic. Although it addressed diabetic neuropathies, the resource focused specifically on Peripheral diabetic neuropathy and lower-limb care, and it was evaluated for content and appearance by experts and the target audience, showing positive results [6]. Another study, concerning the development and evaluation of a mobile health education application on comorbidities of Diabetes mellitus, addressed the topic of neuropathies only superficially and was evaluated solely by subject-matter experts, without the essential participation of the target audience in the evaluation process [25]. In this regard, both studies addressed the development and evaluation of educational technologies related to diabetic neuropathies; however, they did not encompass the different types and complexities of these conditions, unlike the technology evaluated in the present study, which resulted in an educational booklet covering the various types of diabetic neuropathies and was evaluated by both experts and the target audience [8].

The process of evaluating educational technology in terms of content, appearance, and semantics was crucial for assessing the visual suitability of verbal and non-verbal language, with the goal of creating a closer connection with the target audience. The shades of blue used in the technology were maintained, as they are reminiscent of “Blue November” and, more specifically, November 14th, World Diabetes Day, a time when, especially in primary and secondary care at the outpatient level, there is an intensification of health education actions about Diabetes and its main comorbidities, fostering patient engagement with the topic [26, 27].

Regarding health education initiatives aimed at individuals with Diabetes mellitus and Diabetic neuropathies in Brazil, it is observed that many educational technologies are developed and promoted by nursing students during their undergraduate training. However, these productions often lack methodological rigor, being based predominantly on empirical approaches. In this sense, the relevance of the evaluation process for such technologies is emphasized. Educational technological tools that undergo a structured evaluation process can support the provision of more comprehensive care, grounded in scientific evidence rather than solely in creative work processes, thus constituting an important resource for contemporary nursing practice [5].

In this context, it is essential to evaluate educational products to improve elements that foster a connection with the target audience, making the teaching-learning process easier, since the recipient of the information will feel adequately represented through information and images that often reflect their clinical, daily, and cultural reality, as occurred in the evaluation stages of this study [26, 28].

As a limitation, it is noted that educational technology still needs to undergo implementation in primary healthcare units and secondary outpatient care to verify its effectiveness among patients with Diabetes/Neuropathies. Therefore, the aim is for this action to be carried out in a subsequent study.

CONCLUSION

With the implementation and completion of the two evaluation stages proposed by the study, it was confirmed that the booklet entitled “Let’s Talk About Diabetic Neuropathies?” is a statistically adequate educational technology suitable for use and dissemination among both the scientific community and the target audience. The technology achieved an overall CI of 0.91, as well as a score higher than ten in all the evaluations by appearance specialists. The semantic evaluation was also favorable, with a total IS of 0.98.

Through the execution of the project, the importance and magnitude of developing educational technologies to contribute to the advancement of contemporary health practices became evident, as they are facilitating tools that promote the connection between scientific knowledge and the target audience. Following the technological creation stage, the evaluation process serves to reaffirm the importance of the material and to improve it, thus supporting evidence-based practices in the field of nursing.

DECLARATION

The figures presented in this manuscript were created using Canva (www.canva.com) and are original representations prepared by the authors.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: V.F.F.de A., E.T., R.C.V., J.S.B.: Data Analysis or Interpretation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| DM | = Diabetes Mellitus |

| SAM | = Suitability Assessment of Materials |

| ICF | = Informed Consent Form |

| AI | = Artificial Intelligence |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was conducted in accordance with Resolution 466/12 of the Brazilian National Health Council and was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the State University of Pará (Universidade do Estado do Pará – UEPA), Brazil under opinion number 6.737.045, and registered under the Certificate of Presentation of Ethical Appreciation (CAAE): 78331224.5.0000.5170.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of this article are available in Zenodo at 10.5281/zenodo.17543219, reference number 10.5281/zenodo.17543219.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.