All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Using the Recovery Knowledge Inventory Scale (RKI) to Assess Nurses' Knowledge of a Recovery-Oriented Mental Health Care Approach: Findings from a Developing Country

Abstract

Introduction

Recovery-oriented mental health services are being implemented in various countries. However, to implement recovery-oriented mental health care, it is crucial for healthcare workers to understand it first. Therefore, the aim was to assess nurses' knowledge of a recovery-oriented mental health care approach using the recovery knowledge inventory scale (RKI).

Methods

The study utilized a cross-sectional quantitative design and 152 nurses consented to participate in the study. The RKI was used to collect data from four mental health facilities across Botswana. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27. Cronbach's alpha was used to test the reliability of the variables used in the study.

Results

The sample included 81 (53.3%) female and 71 (46.7%) male nurses. The RKI was valid at Cronbach’s alpha 0.6. Most respondents (97%) agreed with the nonlinearity of recovery, while 84.9% strongly agreed or agreed that recovery from mental illness could be achieved by following a set of procedures.

Discussion

The results indicated that after validity and reliability tests were conducted, and with some adjustments, the RKI was valid and reliable for assessing nurses’ knowledge of a recovery-oriented mental health care approach in Botswana. Although its reliability was average at Cronbach's alpha of 0.6, it offered insight into how respondents perceived recovery. Overall, nurses in this study lacked orientation to recovery-oriented services.

Conclusion

There was a clear lack of knowledge of the recovery approach among the respondents. This study underscores the need for targeted training to improve nurses' understanding of recovery-oriented practices.

1. INTRODUCTION

The recovery-oriented mental health care approach emerged from Western countries as a new vision and a beacon of hope for mental health services as it sets a trajectory for recovery [1, 2]. However, the meaning of recovery in the context of mental illness is still being discussed; it is difficult to identify a definition of recovery that applies to everyone [3], and there is an element of personal experience attached to its meaning [4]. This suggests that the recovery concept is often shaped by publications describing the experiences of consumers and mental health service users on how they cope with and live with mental illness [5].

A commonly acknowledged contextualized definition of recovery is “a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with limitations of the illness” [6]. It involves individuals engaging in activities that bring them joy despite being diagnosed with mental illness [7]. Others view it as a process of self-discovery following a diagnosis of mental illness [8]. Individuals with a mental illness diagnosis recognize that returning to a premorbid state may not be possible but find hope in the possibility of living well with the condition.

Several governments and mental health services in well-developed Western countries have adopted the recovery concept [9, 10]. A scoping review [2], indicated that the recovery-oriented approach is effective. Studies have documented that people with mental illness have shown significant improvements in their lives, including enhanced quality of life, reduced hospital stays, increased community participation, improved self-image and self-esteem, and appreciation for the recovery-oriented approach to managing mental illness [11-13]. Despite these positive outcomes, there is still no clear and shared definition of recovery in mental health.

To gain a deeper understanding of the recovery-oriented approach and improve its application, various tools have been developed to assess health workers' comprehension of the recovery concept. The Recovery Knowledge Inventory (RKI) is one such instrument developed in the United States by [14]. The RKI measures healthcare workers' and patients' attitudes toward the recovery-oriented mental health care approach. It has also been used to assess healthcare workers' knowledge of recovery-oriented mental health care to identify their training needs in understanding and implementing the concept [14]. The scale consists of 20 items addressing different components of recovery. The RKI includes four domains: roles and responsibilities in recovery, nonlinearity of the recovery process, the roles of self-definition and peers in recovery, and expectations regarding recovery [14]. Items are rated on a 1 to 5 Likert scale, with 1 representing strongly disagree and 5 representing strongly agree.

The RKI has been adopted in various studies to measure healthcare workers' knowledge of recovery-oriented approaches and has been found to be effective. In the Netherlands [15], used the Dutch 14-item version of the RKI (α = 0.80) to assess general recovery knowledge among 210 health professionals who participated in a recovery intervention program. The results showed improvements in participants' recovery knowledge. In Italy [16], assessed the effectiveness of a short personal recovery training program for mental health professionals using the RKI, and the results also showed improved recovery knowledge.

In Norway [17], validated an adapted version of the RKI among mental health workers and measured their attitudes and knowledge regarding recovery. The scale was translated into Norwegian and tested on a sample of 317 mental health care workers. Despite challenges with its psychometric properties, the RKI provided insight into how participants understood recovery-oriented care. The results indicated a general need for greater knowledge of the recovery-oriented approach compared to countries such as the United Kingdom. The authors suggested that this difference may be due to Norway still being in the early stages of adopting the recovery approach and not yet having dedicated national programs supporting it.

The recovery-oriented approach to mental health services in Africa has not yet been fully accepted. A scoping review [2] indicates that Africa still lacks policy development, adoption, and implementation of recovery-oriented mental health care in practice. In South Africa, the recovery approach has been adopted at the policy level; however, it has not yet been fully translated into mental health services [18]. A study from South Africa also indicated a general lack of awareness of the recovery-oriented approach to mental illness [19].

As a neighboring country to South Africa, Botswana is a southern African nation whose mental health services remain dominated by biomedical orientations [2]. The country is served by only one main mental health referral hospital, and most mental health services across Botswana are delivered by nurses [20]. To progress and adopt best practices in mental health care, Botswana should integrate the recovery-oriented approach to improve patient care [21]. To achieve this, it was necessary to assess nurses' knowledge of the recovery-oriented approach using the RKI in a non-Western context. The aim of this study was not to validate the RKI but to understand how nurses, who constitute the majority of mental health care workers in the country, conceptualize the recovery-oriented care approach. This study aimed to assess knowledge of the recovery-oriented mental health care approach among nurses in Botswana using the RKI. Additionally, the study explored the psychometric properties of the RKI within this context.

2. METHODS

This study employed a quantitative cross-sectional design to understand how nurses in Botswana perceive the recovery-oriented mental health care approach. This design was suitable for the study, as the intent was not to follow individuals over time but to gather preliminary data at once for use in future studies [22].

2.1. Context

According to [23], a context is the “setting in which a phenomenon is studied.” The study was conducted in four mental health facilities in Botswana: Sbrana Psychiatric Hospital, Letsholathebe Memorial Hospital, Nyangabwe Referral Hospital, and Scottish Livingstone Hospital. Sbrana Psychiatric Hospital has a bed capacity of 300 and is located in the town of Lobatse in South East Botswana; it is the only referral hospital in the country. The other three hospitals are located in the North West, North East, and South West regions of Botswana, and each has a mental health wing that serves a maximum of 15 patients at a time [20]. These mental health units primarily function as holding bays for patients in transit to the referral hospital.

2.2. Population and Sample

A study population refers to the group of individuals in a particular area who exhibit the qualities the researchers intend to study [24]. For this study, the total population of nurses across the four study sites was 242. Only 76 nurses held a qualification in mental health nursing; the rest were general nurses. The inclusion criteria required that participants be nurses who had worked in a mental health facility for at least three years, provided direct care to people with mental illness, and held a minimum diploma in nursing. Using the RAOSOFT sample size calculator with a default confidence level of 95% and a 5% margin of error, the required sample size was 149. A total of 170 questionnaires were distributed to account for incomplete or spoiled questionnaires. Only 152 nurses consented to participate in the study, and all completed and returned the questionnaires.

2.3. Data Collection Procedure

Once all research permits were issued by the relevant ethics committees, the researcher identified the gatekeeper and explained the purpose and objectives of the study, as well as the expectations for its completion. The study was then advertised for two weeks, from early February to mid-February 2022, via notice boards. Gatekeepers in each facility identified mediators, who helped the researchers share the study objectives with potential participants in all targeted facilities. The researchers provided the questionnaires to the mediators, who then distributed them to all who had consented to participate. Respondents were given one month to complete and return the questionnaire. All respondents signed a consent form prior to participation.

2.4. Data Collection Tool

The data collection tool was divided into two parts: demographic variables and the RKI. The RKI includes four recovery structures: roles and responsibilities in recovery (7 statements), nonlinearity of the recovery process (6 statements), the roles of self-definition and peers in recovery (5 statements), and expectations regarding recovery (2 statements) [14]. Items on the RKI were rated on a 1 to 5 Likert scale, with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 5 representing “strongly agree.” Nurses were asked to rate their level of agreement with statements on recovery concepts. The RKI was administered in English, as all nurses received training in English, and English is the official workplace language in Botswana. The developers of the RKI [14] granted permission for its use in the current study.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

To ensure compliance with the Helsinki Declaration, the North-West University NuMIQ Scientific Research Committee granted ethical approval to conduct the study, which was further cleared by the Faculty of Health Research Ethics Committee (NWU-HREC); ethics number NWU-00306-21-A1. The researcher used the HREC approval to obtain permission from the Ministry of Health and Wellness Research and Ethics Committee in Botswana (REF NO: HPDME 13/18/1), as well as goodwill permissions from the participating hospitals. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study, and all signed a consent form to participate. Codes were used to protect the identity of individuals.

2.6. Data Analysis Procedure

Data analysis involves reviewing, coding, and entering data into statistical software packages for analysis [25]. Quantitative data from the demographic variables and the RKI (Annexure 1) were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27. Frequency tables were used to present the participants' demographic profiles. Given that the RKI is already segmented into four constructs, Cronbach’s alpha was used to confirm the reliability of each construct. Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.8 and above are commonly regarded as excellent [26], while values of 0.7 or 0.6 are often considered acceptable [27]. For this study, a Cronbach’s alpha of at least 0.6 indicated that the variables in a construct exhibited acceptable internal consistency, as recommended by [27], and could be regarded as measuring the same construct. In instances where items within a construct did not yield a Cronbach’s alpha of at least 0.6, the researcher iteratively deleted items that reduced the reliability of the construct, based on the Alpha When Item Deleted statistic, as described in [28]. The Alpha When Item Deleted indicates the Cronbach’s alpha after removing a given variable. Items that lowered the alpha were deleted, and the reliability test was rerun. This iterative process continued until the minimum required Cronbach’s alpha was achieved.

Validity refers to the degree to which a research instrument accurately measures what it intends to measure [29]. Construct validity was used to assess the validity of the RKI. According to research [30], construct validity describes the extent to which an instrument accurately measures what it is intended to measure within a particular context. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was used to confirm the validity of the constructs. To ascertain construct validity, the standardized path coefficients and goodness-of-fit statistics were examined. Standardized path coefficients determine the latent variable explanation coefficient of each construct [31]. A significant p-value (p < 0.05) for a standardized path coefficient indicates that the item significantly belongs to the construct to which it was assigned in the RKI. For goodness-of-fit tests, the study used the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Based on the benchmarks described by [32], CFI and NNFI values should be at least 0.95, and both RMSEA and SRMR values should be at most 0.08 for the CFA model to be considered a good fit for the data. Following reliability testing with Cronbach’s alpha and validity testing with CFA, stacked bar charts were used to present participants’ responses per construct. This approach assisted in exploring and describing the nurses' understanding of the concept of recovery-oriented mental health care in Botswana.

3. RESULTS

An existing tool, the RKI, was used to assess nurses' knowledge of recovery in mental health care. A total of 152 questionnaires were received for analysis. Only three questionnaires did not meet the inclusion criteria and were therefore excluded. Data were presented using bar charts. The constructs and statements of the RKI [14] were used to structure the results. This section describes the demographic variables, followed by the construct reliability test results, construct validity test results, and the respondents' perceptions on the Roles and Responsibilities of Recovery, Nonlinearity of Recovery, the Roles of Self-Determination and Peers in Recovery, Expectations Regarding Recovery, and the conclusion.

3.1. Demographic Variables of Participants and Occupational Attributes

Table 1 shows that most respondents in this study were female (53.3%), while their male counterparts made up the remaining 46.7%. Only 13.8% of the respondents were nurse managers; the rest worked as support staff. In addition, most nurses had a diploma in general nursing, 15.8% had a degree in nursing, and only 4.6% had a master's degree. Most respondents were working as general nurses without a qualification in mental health, and only 44.7% were qualified.

3.2. Construct Reliability Test Results

The tool (RKI) was tested for reliability and consistency, as shown in Table 2. The items in the constructs on “Nonlinearity of Recovery” and “The Role of Self-Definition and Peers in Recovery” demonstrated acceptable internal consistency. They were regarded as measuring the same constructs, meaning that an aggregate score could be computed to represent participants' responses for these constructs. However, this acceptable reliability was achieved only after removing the item “NLR13_Symptom management is the first step toward recovery from mental illness/substance abuse” from the Nonlinearity of Recovery construct and the item “RSP18_All professionals should encourage clients to take risks in the pursuit of recovery” from the Role of Self-Definition and Peers in Recovery construct. These items jeopardized the internal consistency of their respective constructs based on the “Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted” statistic.

For the constructs on “Roles and Responsibilities of Recovery” and “Expectations Regarding Recovery,” the items did not demonstrate acceptable internal consistency, as the Cronbach’s Alpha values for these constructs were below the acceptable minimum of 0.6. Additionally, the “Cronbach’s Alpha if Item Deleted” statistics did not indicate that removing any items would improve the alpha values. Therefore, the items in these constructs were not regarded as measuring the same constructs, and the results are reported per item rather than per construct.

| - | - | n [Mean] | % [SD] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 81 | 53.3 |

| Male | 71 | 46.7 | |

| Total | 152 | 100 | |

| Occupation | Nurse | 131 | 86.2 |

| Nurse manager | 21 | 13.8 | |

| Total | 152 | 100 | |

| Age | - | [38.21] | [6.721] |

| Educational background | Diploma in Nursing | 121 | 79.6 |

| Degree in Nursing | 24 | 15.8 | |

| Master’s degree in nursing | 7 | 4.6 | |

| Total | 152 | 100 | |

| Work status | General nurse | 84 | 55.3 |

| Psychiatric mental health nurse | 68 | 44.7 | |

| Total | 152 | 100 | |

| Department | Outpatient Department | 62 | 40.8 |

| Psychiatric ward | 90 | 59.2 | |

| Total | 152 | 100 | |

| Experience working in a mental health facility | - | [7.60] | [3.917] |

| - | Cronbach's Alpha | N of Items |

|---|---|---|

| Roles and responsibilities of recovery | 0.538 | 7 |

| Nonlinearity of recovery | 0.663 | 4 |

| The role of self-definition and peers in recovery | 0.693 | 4 |

| Expectations regarding recovery | 0.394 | 2 |

| Factor1 | Estimate | Std. Err | z-value | p-value | Std.lv | Std. all |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR1 | 0.645 | 0.153 | 4.222 | 0.000 | 0.645 | 0.447 |

| RRR2 | 0.338 | 0.123 | 2.751 | 0.006 | 0.338 | 0.322 |

| RRR3 | 0.473 | 0.130 | 3.637 | 0.000 | 0.473 | 0.412 |

| RRR4 | 0.342 | 0.133 | 2.567 | 0.010 | 0.342 | 0.307 |

| RRR5 | 0.528 | 0.126 | 4.174 | 0.000 | 0.528 | 0.450 |

| RRR6 | 0.505 | 0.159 | 3.174 | 0.002 | 0.505 | 0.382 |

| RRR7 | 0.382 | 0.132 | 2.901 | 0.004 | 0.382 | 0.314 |

| Factor2 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| NLR8 | 0.531 | 0.083 | 6.395 | 0.000 | 0.531 | 0.571 |

| NLR9 | 0.377 | 0.066 | 5.741 | 0.000 | 0.377 | 0.512 |

| NLR10 | 0.328 | 0.047 | 6.955 | 0.000 | 0.328 | 0.599 |

| NLR11 | 0.442 | 0.057 | 7.717 | 0.000 | 0.442 | 0.675 |

| NLR13 | 0.235 | 0.074 | 3.166 | 0.002 | 0.235 | 0.296 |

| Factor3 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| RSP14 | 0.339 | 0.058 | 5.845 | 0.000 | 0.339 | 0.524 |

| RSP15 | 0.488 | 0.062 | 7.859 | 0.000 | 0.488 | 0.671 |

| RSP16 | 0.375 | 0.064 | 5.830 | 0.000 | 0.375 | 0.519 |

| RSP17 | 0.559 | 0.070 | 7.999 | 0.000 | 0.559 | 0.684 |

| RSP18 | 0.290 | 0.102 | 2.849 | 0.004 | 0.290 | 0.263 |

| Factor4 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ER19 | 0.667 | 0.253 | 2.639 | 0.008 | 0.667 | 0.553 |

| ER20 | 0.472 | 0.186 | 2.540 | 0.011 | 0.472 | 0.447 |

| - | Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) | Root Mean Square error of Approximation (RMSEA) | standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author’s model | 0.766 | 0.725 | 0.065 | 0.077 |

| [32] | At least 0.9 | At least 0.95 | Less than 0.08 | Less than 0.08 |

3.3. Construct Validity Test Results for the RKI

CFA was used to ascertain the construct validity of the RKI, which was used to assess nurses' knowledge of recovery-oriented care. From the CFA, the standardized path coefficients and the goodness-of-fit indices were generated and are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

The construct validity test, performed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), resulted in the removal of NLR12 from Factor 2 (Nonlinearity of Recovery), as it did not significantly belong to this construct (p-value 0.144, which is greater than the significance level of 0.05). Therefore, Table 3 was generated by re-running the CFA after removing NLR12. The results show that all the p-values of the remaining items are significant at the 5% level (p-values < 0.05). These findings confirm that each item significantly belongs to its respective construct, indicating that the constructs are valid. Table 4 presents the fit indices.

Table 4 shows that based on the Absolute Fit Indices (RMSEA and SRMR), which measure how well the model fits the data compared to no model at all, the model fits well. However, the Incremental Fit Indices (CFI and TFI), which compare the fitted model to a baseline model, indicate that the fitted CFA model does not fit the data well. These opposing results may be due to the small dataset used in this study, which is known to affect the SRMR and NNFI [33]. Since the indices do not agree regarding construct validity but are on the borderline (i.e., two indicate a good fit while two do not), the results cannot be generalized to all nurses working in mental health facilities in Botswana. This goodness-of-fit outcome may also explain why some of the construct items were inconsistent based on the reliability test results in Table 2. Following the reliability and validity test results, the responses from the participants are presented in the next subsections.

3.4. Perception of the Nurses on the Roles and Responsibilities of Recovery

This construct of the RKI had seven items: “Only people who are clinically stable should be involved in making decisions about their care.” “Recovery from mental illness is achieved by following a set of procedures.” “It is the responsibility of professionals to protect their clients against possible disappointments.” “The idea of recovery is relevant for those who have completed or are close to completing active treatment.” “People with mental illness/substance abuse should not be burdened with the responsibility of everyday life.” “People receiving psychiatric/substance abuse treatment are unlikely to be able to decide their own treatment and rehabilitation goals” [14]. Each item under this construct was interpreted individually because the seven variables did not show acceptable internal consistency, indicating that they could not be reported as a single construct. Table 5 summarizes the participants' responses for each of these items.

Table 5 indicates that respondents had varied views regarding the statement that only people who are clinically stable should be involved in making decisions about their care. In this study, 17% strongly disagreed and 29% disagreed with the statement, while 22% strongly agreed or agreed. Nine percent of the respondents were undecided.

| - | - | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Only people who are clinically stable should be involved in making decisions about their care. | Strongly disagree | 26 | 17 |

| Disagree | 44 | 29 | |

| Uncertain | 13 | 9 | |

| Agree | 36 | 24 | |

| Strongly agree | 33 | 22 | |

| Recovery in serious mental illness/substance abuse is achieved by following a prescribed set of procedures. | Strongly disagree | 7 | 5 |

| Disagree | 11 | 7 | |

| Uncertain | 5 | 3 | |

| Agree | 74 | 49 | |

| Strongly agree | 55 | 36 | |

| It is the responsibility of professionals to protect their clients against possible failures and disappointments. | Strongly disagree | 10 | 7 |

| Disagree | 11 | 7 | |

| Uncertain | 21 | 14 | |

| Agree | 61 | 40 | |

| Strongly agree | 49 | 32 | |

| The idea of recovery is most relevant for those people who have completed, or are close to completing, active treatment. | Strongly disagree | 7 | 5 |

| Disagree | 32 | 21 | |

| Uncertain | 17 | 11 | |

| Agree | 74 | 49 | |

| Strongly agree | 22 | 14 | |

| People with mental illness/substance abuse should not be burdened with the responsibilities of everyday life. | Strongly disagree | 38 | 25 |

| Disagree | 63 | 41 | |

| Uncertain | 14 | 9 | |

| Agree | 31 | 20 | |

| Strongly agree | 6 | 4 | |

| People receiving psychiatric/substance abuse treatment are unlikely to be able to decide their own treatment and rehabilitation goals. | Strongly disagree | 27 | 18 |

| Disagree | 53 | 35 | |

| Uncertain | 7 | 5 | |

| Agree | 50 | 33 | |

| Strongly agree | 15 | 10 | |

| Recovery is not as relevant for those who are actively psychotic or abusing substances. | Strongly disagree | 31 | 21 |

| Disagree | 58 | 38 | |

| Uncertain | 24 | 16 | |

| Agree | 26 | 17 | |

| Strongly agree | 12 | 8 |

Recovery from mental illness is achieved by following a set of procedures.

Most nurses in this study (84.9%) strongly agreed or agreed that recovery from mental illness could be achieved by following a set of procedures. Only 5% strongly disagreed, 7% disagreed with the statement, and 3% were uncertain.

It is the responsibility of professionals to protect their clients against possible disappointments.

Seventy-two percent (72.3%) of the respondents strongly agreed, forty percent (40%) agreed, and thirty-two percent (32%) agreed that it is the responsibility of professionals to protect their clients against possible disappointments. Fourteen percent (14%) of the respondents were uncertain, while seven percent (7%) strongly disagreed and seven percent (7%) disagreed with the statement.

The idea of recovery is relevant for those who have completed or are close to completing active treatment.

Nurses in this study agreed (49%) and strongly agreed (14%), totaling 63.2%, that the idea of recovery is relevant for those who have completed or are close to completing active treatment. Twenty-one percent (21%) disagreed, five percent (5%) strongly disagreed, and eleven percent (11%) were uncertain.

People with mental illness or substance abuse should not be burdened with the responsibility of everyday life.

Most respondents (65%) showed some orientation to recovery regarding this concept, as they strongly disagreed (25%) and disagreed (41%) that people with mental illness or substance abuse should not be burdened with the responsibility of everyday life. Twenty percent (20%) agreed, four percent (4%) strongly agreed, and nine percent (9%) were uncertain.

People receiving psychiatric or substance abuse treatment are unlikely to be able to decide their own treatment and rehabilitation goals.

Fifty-two percent (52.7%) strongly disagreed, eighteen percent (18%) disagreed, and thirty-eight percent (38%) disagreed that people receiving psychiatric or substance abuse treatment are unlikely to decide their own treatment and rehabilitation goals. In contrast, 17% agreed and 8% strongly agreed.

Recovery is not as relevant for those actively psychotic or abusing substances.

More than half of the respondents (58.9%) strongly disagreed (21%) and disagreed (38%) with the statement that recovery is not relevant for those who are actively psychotic or abusing substances. Seventeen percent (17%) agreed and eight percent (8%) strongly agreed. Sixteen percent (16%) were uncertain. Although responses varied, the results suggest that most nurses in this study had a good orientation to recovery, since recovery is regarded as relevant for all people with severe mental illness.

3.5. Perception of Nurses on the Nonlinearity of Recovery

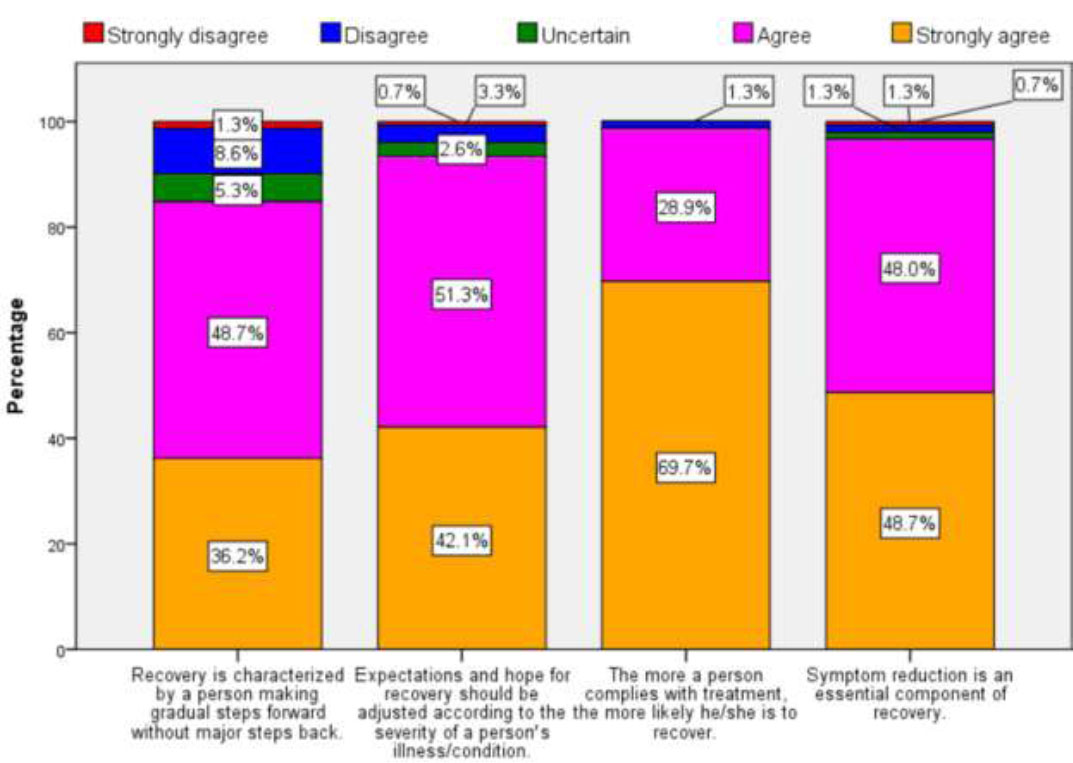

This construct of the RKI was treated as measuring the same concept, and its items were found to be consistent after removing NLR 12 and NLR 13 based on the reliability test. Since the items within this construct were internally consistent, the results are presented for the construct as a whole rather than for individual items, unlike the construct on the perception of nurses regarding the roles and responsibilities of recovery (Fig. 1).

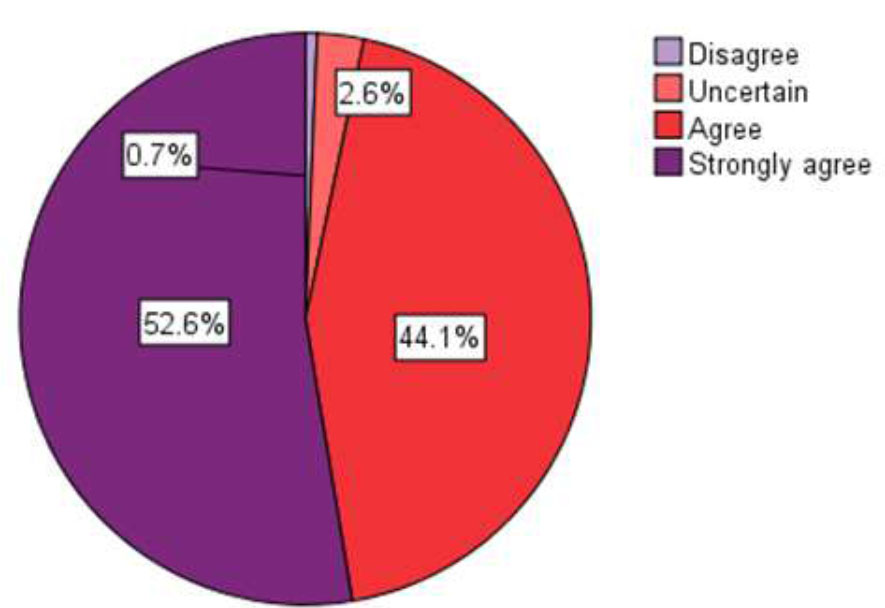

Respondents in this study generally agreed with the concept of the non-linearity of recovery. A substantial proportion of participants (36.2% to 48.7%) strongly agreed or agreed with all statements reflecting the non-linear nature of recovery, including the idea that recovery involves individuals taking gradual steps without experiencing major setbacks. Most respondents strongly agreed (48.7%) and agreed (48.0%) that symptom reduction is essential to the recovery process. Additionally, a large percentage strongly agreed (42.1%) and agreed (51.3%) that expectations and hope for recovery should be adjusted according to the severity of an individual’s illness. Figure 2 (pie chart) provides a summary of the results related to the construct on the non-linearity of recovery.

Figure 2 above shows that on average, the majority of participants strongly agreed that the Non-linearity of recovery plays a role in the mental health care recovery programme (52.6%), followed by those who agreed (44.1%), and the remaining few either were uncertain (2.6%) or disagreed (0.7%). The “strongly disagree” group does not show in the aggregated chart since a negligibly low percentage (less than 0.05%) of the respondents belonged to this group.

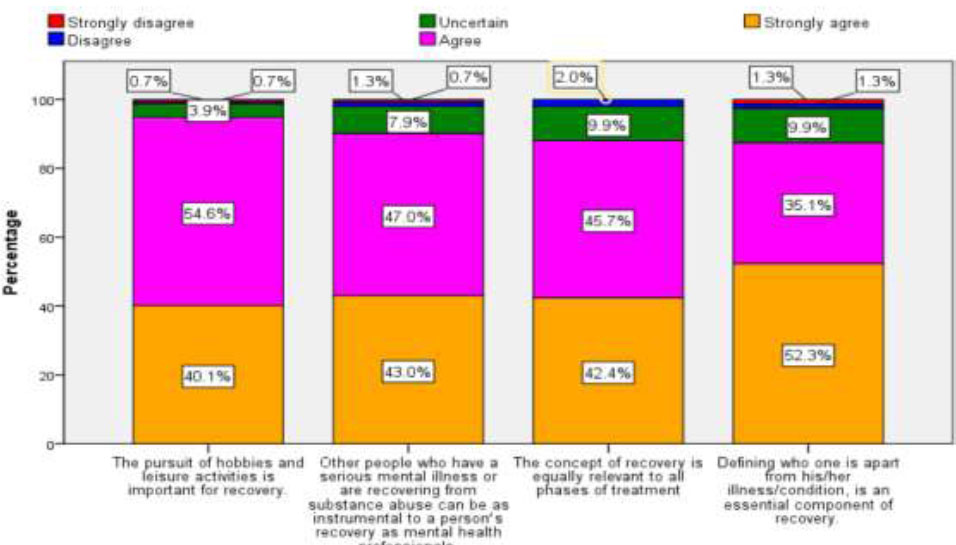

3.6. Roles of Self-determination and Peers in Recovery

Based on the reliability test for this construct, the items demonstrated acceptable internal consistency. Therefore, the results are presented for the construct as a whole, rather than for each individual item, which contrasts with the approach used for the construct on nurses’ perceptions of the roles and responsibilities in recovery.

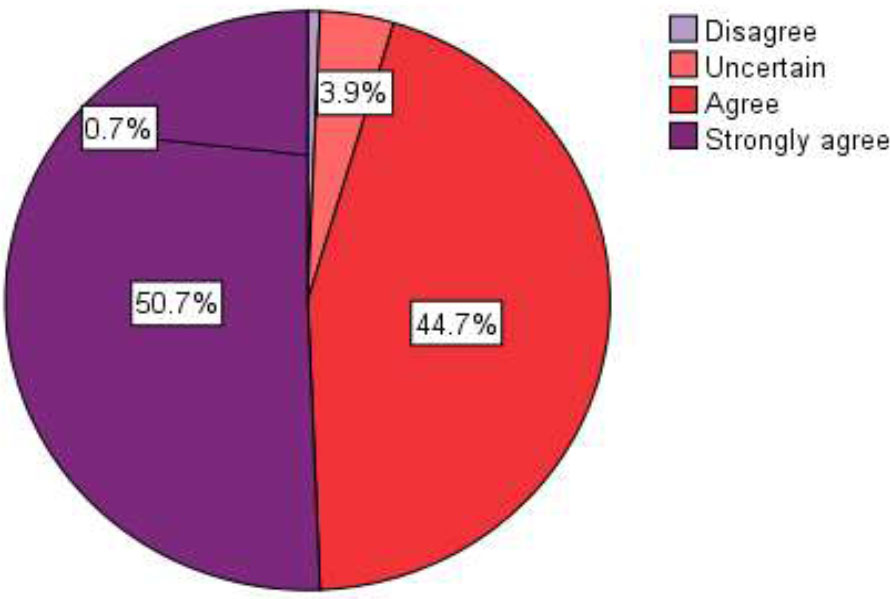

Figure 3 shows that the highest percentage of respondents (45.7% to 54.6%) agreed with all statements related to the roles of self-definition and peers in recovery, except for the statement “Defining who one is apart from his/her illness or condition is an essential component of recovery,” for which the highest percentage strongly agreed (52.3%). The second-highest percentage of respondents (40.1% to 43%) strongly agreed with all statements in this construct, except for the same statement, for which the highest percentage agreed (35.1%). Only a small proportion of respondents disagreed (0.7% to 2.0%) or strongly disagreed (0.7% to 1.3%) with any of the statements. Figure 4 summarises the results for the construct on the roles of self-definition and peers in recovery.

Showing perception of nurses of the nonlinearity of recovery. Each statement has five colours representing: gold (strongly agree), purple (agree), dark green (uncertain), blue (disagree), and red (strongly disagree). Overall, the respondents agreed with the non-linearity of recovery.

Showing the results for the construct on non-linearity of recovery. The different colours represent: dark purple (strongly agree), red (agree), light orange (uncertain), and light purple (disagree). Overall, the respondents agreed with the non-linearity of recovery.

Roles of Self-determination and peers in recovery. The different colours represent: gold (strongly agree), light purple (agree), dark green (uncertain), blue (disagree), and red (strongly disagree). Overall, the respondents agreed with the statement on the role of self-determination and peers in recovery.

Showing a summary of roles of self-determination and peers in recovery. Different colours represent: dark purple (strongly agree), red (agree), light orange (uncertain), and light purple (disagree). Strongly disagree represented an insignificant value, as it is not reflected on the pie chart.

| - | - | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not everyone is capable of actively participating in the recovery process | Strongly disagree | 15 | 10% |

| Disagree | 34 | 23% | |

| Uncertain | 23 | 15% | |

| Agree | 61 | 40% | |

| Strongly agree | 18 | 12% | |

| It is often harmful to have too high expectations for clients. | Strongly disagree | 7 | 5% |

| Disagree | 19 | 13% | |

| Uncertain | 21 | 14% | |

| Agree | 77 | 51% | |

| Strongly agree | 27 | 18% |

The pie chart above shows that, on average, most respondents strongly agreed that the roles of self-definition and peers contribute meaningfully to the mental health recovery programme (50.7%), followed by those who agreed (44.7%). A small proportion were uncertain (3.9%), and only 0.7% disagreed. The “strongly disagree” category does not appear in the aggregated chart because a negligibly small percentage of respondents (less than 0.05%) fell into this group. Overall, 51% of respondents strongly agreed, and 45% agreed—indicating that 96% believed that self-determination and peer involvement are vital in the recovery of people diagnosed with SMI.

3.7. Nurses’ Expectations on Recovery

Each item under this construct was interpreted individually because the four items did not demonstrate acceptable internal consistency based on the reliability test. This indicates that they cannot be reported as a unified construct. Therefore, the results are presented for each item separately, as was done for the construct on nurses’ perceptions of the roles and responsibilities in recovery. Table 6 summarises the participants’ responses for each item.

Most respondents in this study strongly agreed (12%) and agreed (40%)—a combined total of 52%—with the statement that not everyone is capable of actively participating in the recovery process. Twenty-three per cent (23%) disagreed, and 10% strongly disagreed with the statement. Fifteen per cent (15%) of the respondents were uncertain about whether everyone is capable of participating in the recovery process.

4. DISCUSSION

The aim of the study was to assess nurses’ understanding of recovery-oriented mental health care using the RKI. For this study, the RKI was found to be consistent (Cronbach’s alpha 0.6) and valid, although this was achieved after the removal of some items from factor 2. The validity and reliability of the RKI have been questioned in other studies, as they reported low factor loading for two of its four constructs [34]. In addition, other studies that used translated versions of the RKI found that the factor structure did not load according to the original version [35, 36], and the developers advised that it be used with caution [14]. However, in this study, the instrument provided valuable information on how nurses viewed the recovery-oriented mental health care approach in the Botswana context after some adjustments. Botswana’s mental health care facilities are mainly staffed with psychiatric mental health nurses and general nurses. Like many other countries, Botswana continues to experience a shortage of mental health personnel [20]. Therefore, nurses are deployed in mental health care facilities and are responsible for caring for people with SMI.

Nurses in this study had varying views about the statement, “Only people who are clinically stable should be involved in making decisions about their care.” Seventeen percent strongly disagreed, 29% disagreed, and 22% strongly agreed or agreed with the statement. Nine percent of the respondents were undecided. The findings of this study were therefore inconclusive regarding this statement. However, findings from a similar study in Japan [37], were conclusive that only clinically stable people should be involved in decisions about their care. In contrast, respondents in a study from Norway [17] strongly disagreed with the statement. Recovery concepts emphasise that recovery can occur with or without symptoms, and everyone can participate in their recovery process if supported and given choices to lead it [38]. In addition [39], in a commentary, noted that people with SMI may not have full control of their symptoms; however, it may still be possible for them to take control of their lives if given opportunities like any other member of society. The results of this study indicated that respondents could not determine whether people with symptoms of mental illness should or should not make decisions about their treatment.

These results suggest that respondents in this study had a poor orientation to the recovery approach, as many believed that one must follow prescribed activities to recover. These findings align with those of [17], whose respondents agreed that to recover from SMI, one should follow a set of procedures. Conversely, respondents in a study from Japan disagreed with the notion that recovery from SMI requires following prescribed procedures. The respondents in this study therefore appeared to lack orientation to the recovery approach. The recovery approach in mental health is self-defined and individualised, experienced differently by each person, and does not follow a prescribed set of steps [38, 39].

The respondents believed that people with SMI should be responsible for and in charge of their recovery process. However, respondents in studies from Japan and Norway disagreed [17, 37]. Recovery from mental illness is a personal journey, and people with SMI should take a central role in their recovery process [37]. Very often, health professionals and family members of people with a diagnosis of SMI tend to have questionable approaches and overprotective tendencies toward clients’ abilities [39]. Recovery principles emphasise looking beyond these barriers and viewing individuals with a diagnosis of SMI as people with the potential to set and achieve their recovery goals [17]. This belief aligns with the person-centred approach by Carl Rogers, which posits that everyone can grow and achieve their desires when cared for in a nurturing environment [40].

The findings of this study also suggest that respondents consider recovery possible only for people who are taking or have taken their treatment. This assumption reflects a low orientation to recovery concepts, as the recovery approach advocates that recovery is possible for all people with SMI, with or without treatment. A similar thinking pattern was noted in the research findings from Norway [17]. In contrast, a study in Japan offered a differing view, as respondents disagreed with the statement [37], indicating a good orientation to recovery concepts on this item.

Most respondents in this study (65%) showed some orientation to recovery on the concept of responsibility in recovery, as they strongly disagreed (25%) and disagreed (41%) that people with mental illness or substance abuse should not be burdened with the responsibility of everyday life. The findings of studies from Japan and Norway agree with the results of this study [17, 37]. These findings suggest that respondents believed that people with SMI should live an everyday life just like everyone else in society. This belief aligns with the recovery approach, which emphasises that people with SMI should be engaged in societal activities and live everyday lives like any other member of society [7]. A systematic review on patient engagement to improve the quality of clients’ care [41], indicated that engagement of people with SMI in everyday activities improved their self-esteem and empowered them. Healthcare professionals and society, therefore, need to appreciate the potential of people with a diagnosis of SMI as separate from their problems [39]. By doing so, society will realise that people with SMI should also be engaged in everyday activities without judgment, supporting their personal growth and well-being.

About 70% strongly disagreed and agreed that people receiving psychiatric or substance abuse treatment are unlikely to decide their own treatment and rehabilitation goals. Supporting this finding, respondents from studies in Norway and Japan [17, 37] disagreed or strongly disagreed with the same statement. These findings suggest that respondents in this study had a high orientation to the recovery principle that people with SMI can take care of themselves and can set their own recovery goals. This aligns with the theory of self-determination, which asserts that all individuals strive for growth and well-being and will thrive if given support and encouragement [42]. Therefore, health professionals should see beyond the illness of the client and must not underestimate the power of self-determination in individuals under their care. Recovery involves seeing beyond clients’ problems and fostering a sense of purpose and growth in them [39].

It is believed that everyone, as per client-centered therapy, has inherent qualities that can facilitate their recovery [42]. Findings from studies in Japan and Norway concur with the results of this study. Most interventions in the recovery literature aim to improve clients’ symptoms and functioning [43]. recommended that health professionals look beyond symptom management and foster a sense of hope, belief, empowerment, and meaningful life in patients. Studies on patients’ narratives of recovery have shown that they describe recovery as having a meaningful life, social functioning, and hope despite the presence of mental illness symptoms [44, 45].

The respondents in this study agreed with the nonlinearity of recovery. This implies that respondents perceived recovery to be associated with a person with a diagnosis of mental illness making gradual steps forward, not backward, and complying with treatment to reduce symptoms as instrumental to recovery. It also suggests that nurses in this study believed that the severity of clients’ symptoms would determine expectations about the patient’s recovery. Finally, the findings suggested that participants lacked knowledge of what recovery constitutes, since the recovery approach advocates that everyone diagnosed with SMI can recover with or without treatment. In a study from Australia by [46], the perception of the recovery approach using RKI among mental health care practitioners did not align with the nonlinearity of recovery. The results showed a low mean score of 2.94 for the construct on nonlinearity of recovery. This finding indicated that participants viewed recovery as an individualized process that does not follow a linear pattern. Australia has embraced the concept of recovery, and the Government has developed and implemented recovery in mental health settings [47]. This could explain why the staff disagreed with the nonlinearity of recovery, as participants had received training on implementing recovery-oriented services.

Respondents in this study strongly agreed (51%) and agreed (45%), making 96%, that self-determination and peers were vital in the recovery of people with a diagnosis of SMI. The findings are corroborated by [41] from Australia and [17] from Norway. The results underscore the importance of support from significant others and self-determination in the recovery process of individuals with SMI. According to research on self-determination has identified three critical factors necessary for human motivation and well-being: autonomy, competence, and relationships. The self-determination theory postulates that individuals strive for growth and well-being when supported and that individuals have inherent qualities to meet those needs [42]. People with SMI should be provided with an environment that encourages personal growth and builds resilience by embracing their cultural and spiritual diversity [44, 48]. Furthermore, support in the form of a listening ear from families, peers, and healthcare workers is also helpful in the recovery of people with SMI. Recovery-oriented mental health facilities have been associated with better patient recovery outcomes [34, 49].

Respondents in this study strongly agreed and agreed at a combined score of 52.3% with the item stating that not everyone is capable of participating in the recovery process, and 64.9% agreed with the view that it is often too harmful to have high expectations for clients. The recovery approach is based on the person-centered approach and supports individualized care. Healthcare professionals must see individuals beyond their diagnosis and focus on their strengths and potential [40]. Expectations about recovery between clients and healthcare workers differ. In many cases, healthcare workers expect clients to comply with treatment and set realistic goals for recovery based on the signs and symptoms of their mental illness [50]. Patients, however, believe that support, hope, encouragement, and independent living are instrumental to their recovery [51]. Moreover, findings from a study in Ghana in community-based facilities identified medications, participation in community activities, and finding jobs as facilitators of clients’ recovery [52-54].

5. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution, as it utilized a small dataset, which has the potential to introduce bias. Therefore, the findings are limited to the views of respondents from the four study sites and cannot be generalized as representing all nurses working in mental health facilities in Botswana.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study suggest that nurses lacked knowledge of the recovery approach in mental health care, underscoring the need for targeted training to improve understanding of recovery-oriented practices. Recovery-oriented mental health care is not practiced in Botswana; therefore, this study provides insight into where researchers can begin implementing it.

RELEVANCE FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE

Nurses form the backbone of mental health practice in Botswana. Consequently, they must understand the latest developments in mental health care, such as recovery-oriented practice. The results indicated that the RKI can be adapted and used in different contexts. In addition, the study offered insights into how nurses understand recovery. This knowledge can help policymakers develop appropriate training programs, especially in developing countries like Botswana, where recovery-oriented mental health care is not yet established.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: K.M.K.: Study conception and design, Draft manuscript; S.MP.: Study Conception, Visualization; M.E.M.: Study Conception, Visualisation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| RKI | = Recovery Knowledge Inventory |

| SMI | = Serious Mental Illness |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ministry of Health and Wellness Research and Ethics Committee in Botswana (REF NO: HPDME 13/18/1), North-West University NuMIQ Scientific Research Committee granted the ethical approval to conduct the study, and then further cleared it by the Faculty of Health Research Ethics Committee, South Africa (NWU-HREC); ethics number NWU-00306-21-A1.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

North-West University for partly funding the study through the provision of tuition for the PhD candidate (KK) Prof Montshiwa, the statistician, Prof Bedregal for giving the researcher permission to use the RKI. The participating hospitals allowed the researchers to collect data in their facilities. Nurses who consented to participate in the study.