All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Access to Healthcare in Rural Jordan: Challenges Faced by Nurses and Innovative Solutions - A Narrative Review

Abstract

Introduction

Access to healthcare in rural Jordan presents significant challenges due to geographical isolation, limited resources, and a shortage of medical personnel. This disparity in healthcare services affects the well-being of rural communities, leading to higher rates of untreated illnesses and preventable conditions. This paper explores the challenges faced by rural populations in Jordan and highlights innovative approaches aimed at achieving equitable healthcare access for all populations.

Methods

Several databases were utilized, including PubMed (through MEDLINE), CINAHL, Google Scholar, and ResearchGate. The researchers used different combinations of keywords that mainly incorporate the following terms: rural areas, challenges, and innovative solutions. This narrative review included a total of nineteen studies; eleven of these studies highlighted the prospects and implementation challenges for nurses using telemedicine interventions targeted at enhancing healthcare accessibility in remote areas. Five studies also looked at the function of mobile clinics, namely in assisting nurse-led community health projects and reaching isolated populations. The remaining studies focused on topics, like policy-level innovations, training for rural healthcare delivery, and the distribution of nurses in the workforce.

Results

Key barriers included limited healthcare infrastructure, a shortage of trained personnel, geographical isolation, and cultural factors that complicate patient care. Nurses often contend with inadequate resources, long travel distances, and insufficient professional development opportunities, which hinder effective service delivery. Therefore, innovative approaches, such as mobile health clinics, telemedicine, and community health worker programs, have emerged as promising strategies to address these issues by enhancing outreach and leveraging technology.

Discussion

In rural Jordan, access to healthcare is still severely hampered by systemic, financial, and geographic barriers. This gap can be closed by implementing telemedicine, mobile health units, and community health programs. Continued funding is an essential, sustainable approach to guarantee that rural communities receive high-quality healthcare.

Conclusion

Nurses in rural Jordan are crucial in enhancing healthcare access by delivering primary care through mobile clinics, telehealth, community education, and advocating for rural health policy reforms.

1. INTRODUCTION

Access to medical care in rural Jordan is a major problem, with facilities providing only 60–100% of the required medical services [1]. A substantial proportion of the world's poor population resides in rural areas, and health indicators in developing countries decline markedly as the distance from urban to rural areas increases [2]. In developed countries, urban residents have lower mortality rates than rural residents across a variety of health problems, including cardiovascular diseases and cancers [3, 4].

Studying the factors influencing access to health care, treatment costs, service availability, and the quality of health services is one of the first steps in understanding and addressing the health disparities between urban and rural areas [5].

The health system and opportunities for financing medical care, including bearing the cost of medical treatment, are among the main factors influencing the ability to access quality healthcare [6]. Despite living in urban areas or experiencing poverty, Jordan has observed geographical disparities in morbidity and mortality in rural regions [7]. Rural and remote communities face difficult issues, such as geographic isolation and reduced access to both general and specialist medical services, leading to unmet healthcare needs and negative health outcomes [8].

These disparities in access to healthcare stem from an urban bias, where most public services, including health services, are concentrated in urban centers, leaving those in rural areas either completely without care or being forced to travel long distances to access the care that they need [8, 9]. While healthcare services in Jordan are largely subsidized or free at the point of access through public institutions, many rural residents still experience barriers that make access functionally limited, including transportation costs, long travel distances, and shortages of staff and resources in rural facilities [10]. This creates a disconnect between the availability of free care and the actual ability to utilize it. Hence, this review paper explores the challenges contributing to this situation and proposes a novel and innovative solution. This review is significant because it summarizes current issues and identifies creative, situation-specific solutions that can close these gaps. Through an analysis of effective models and new approaches, the study offers evidence-based insights to community stakeholders, healthcare executives, and legislators to guide future actions. Its ultimate goal is to help Jordan's impoverished rural areas build more robust, easily accessible, and sustainable healthcare systems. This review addresses the following research question: “What are the key challenges faced by nurses in delivering healthcare in rural Jordan, and what innovative solutions have been proposed or implemented to improve access and quality of care in these areas?”

2. METHODS

2.1. Literature Search

This narrative review aimed to identify the studies on healthcare access in rural areas and challenges faced by conducting a search in the following electronic databases: Web of Science, CINAHL, PubMed (through MedLine), and the Jordanian Database for Nursing Research. Research articles on healthcare access were identified using various combinations of keywords, such as “healthcare access” OR “access to health services”; “rural population” OR “rural areas”; “nurses” OR “nursing challenges”; “innovative solutions” OR “health system innovation”; and “patient experience” OR “barriers to care”. The search string used is as follows: [“healthcare access” (MeSH terms) OR “access to health services” (title/abstract)] AND [“rural population” (MeSH terms) OR “rural areas” (title/abstract)] AND [“nurses” (MeSH terms) OR “nursing challenges” (title/abstract)] AND [“innovative solutions” (title/abstract) OR “health system innovations” (title/abstract)]. Full-text articles, published in English, and incorporating either quantitative or qualitative research were included. To ensure the accuracy and applicability of the findings in connection with the present healthcare situation in rural Jordan, only studies published between 2017 and 2025 were included in this review. This period was included to cover recent events, such as modifications to healthcare regulations, technological breakthroughs, and the changing responsibilities and difficulties experienced by nurses in rural areas. Focusing on literature from the past eight years allowed for the incorporation of current information, particularly with regard to innovative solutions that have emerged in response to access difficulties, such as community-based projects, mobile clinics, and telehealth. Additionally, this timeframe aligned with national efforts to improve rural healthcare services and facilitated the inclusion of early online articles scheduled for publication by 2025, ensuring a comprehensive and forward-looking synthesis of the available data. However, unpublished articles, grey literature, student dissertations, theses, and any article not published in the English language were excluded from the search.

3. RESULTS

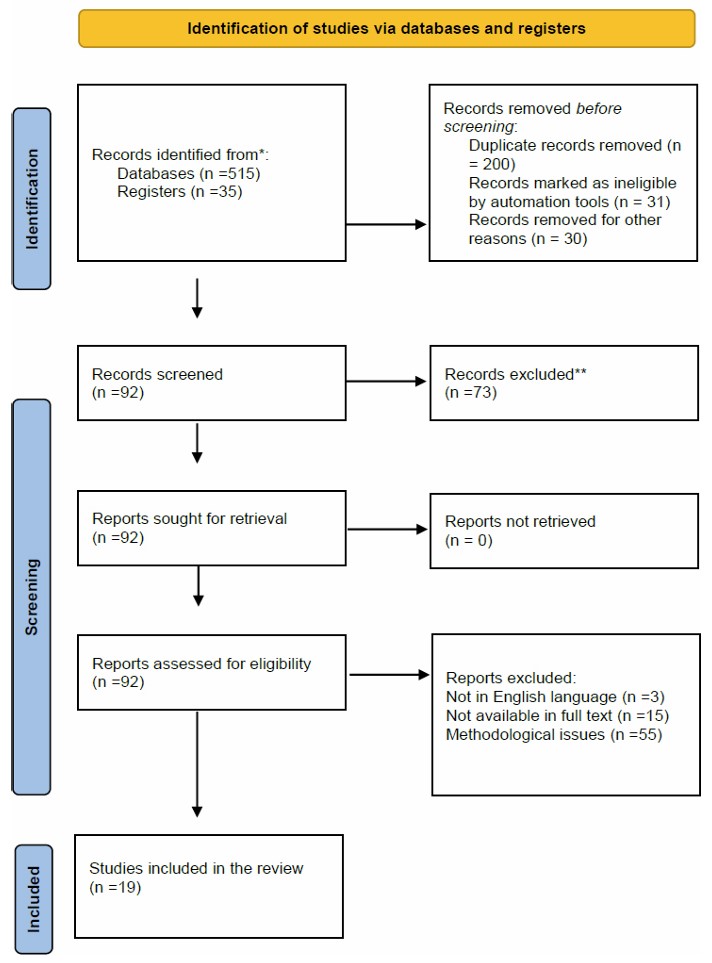

A total of 515 articles were retrieved. After duplicate removal, 477 articles were screened for titles and abstracts. Ninety-two relevant articles underwent full-text screening, of which 37 were found eligible to be included in the review. However, only nineteen studies were included in the current review. The opportunities and implementation challenges faced by nurses utilizing telemedicine treatments aimed at improving healthcare accessibility in rural places were emphasized in eleven of these studies. Five studies also looked at the function of mobile clinics, namely in assisting nurse-led community health projects and reaching isolated populations. The remaining research focused on topics, like policy-level innovations, training for rural healthcare delivery, and the distribution of nurses in the workforce. These revelations can enhance an understanding of the types and areas of emphasis with respect to the creative solutions examined in the literature study. The search strategy and study selection process are shown in Fig. (1).

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.1. Healthcare Infrastructure in Rural Areas of Jordan

Jordan, located in the Middle East, has a population of approximately 11,535,035 as of the latest statistics [11]. Twelve governorates divide the country into three regions: central, northern, and southern. The central region, which includes Amman, Balqaa, Zarqa, and Madaba, accommodates 61% of the population. The northern region, comprising Irbid, Mafraq, Jarash, and Ajloun, accounts for 29.6%, while the southern region, including Karak, Tafila, Ma’an, and Aqaba, constitutes 9.5% [12].

Jordan's healthcare system is categorized into public, private, and non-profit sectors. The public sector includes the Ministry of Health (MoH), the Royal Medical Services (RMS), and the university hospitals. Together, there are over 120 hospitals and medical centers nationwide, with 71 private and 47 public institutions actively providing services [13]. The MoH offers free health services to individuals with government health insurance and provides care at nominal fees for those without such coverage.

The RMS operates 14 hospitals across the kingdom, serving military personnel, their dependents, retirees, and members of the security and armed forces. University hospitals, such as Jordan University Hospital and King Abdullah Hospital, play a vital role in specialized healthcare and medical education [14].

These hospitals and clinics employ an estimated 14,470 nurses and 11,006 physicians, including specialists and general practitioners [15]. Rural Jordan has a wide variety of healthcare facilities; however, staff levels and service quality are still inconsistent. Some places struggle with issues like overcrowded and poorly equipped institutions, which lowers the standard of healthcare. In order to increase access and service quality in these places, efforts are being made to improve primary healthcare and attain universal health coverage [16]. The number of physicians and registered nurses in Jordan is shown in Table 1, stratified by the various categories of public sector institutions.

| Public Sector Categories | No. of Registered Nurses | No. of Registered Physicians |

|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Health | 7975 | 6737 |

| Royal medical services | 4993 | 2919 |

| University hospitals | 1502 | 1350 |

| Total | 14470 | 11006 |

Source: Jordanian Ministry of Health (JMoH; 2023).

A recurrent concern throughout the screening process was the dearth of rural clinics with adequate resources. A community health nurse, for instance, recounted an experience working in a distant town where the clinic had a single blood pressure monitor for the entire week, which was frequently shared between two shifts. Patients had to drive more than 30 kilometers to the closest referral hospital, and essential medications were regularly out of stock. These circumstances not only postpone timely treatment but also discourage women from seeking care entirely, particularly those without access to private transportation. This case illustrates how inadequate infrastructure in rural primary care settings can exacerbate health disparities among vulnerable groups and directly restrict equitable access to necessary healthcare treatments, resulting in inadequate care. Providing rural regions with appropriate healthcare facilities and staff is important in itself [17]. This section aims to illustrate the challenges facing rural Jordan through elucidating specific tangible realities. However, this is not an effortless task. Domestic researchers must conduct more rigorous research due to the limited availability of gleanable information.

3.2. Hospitals and Clinics

In rural areas of Jordan, access to healthcare services remains a significant challenge due to the considerable distance from hospitals and clinics. For many residents, obtaining medical care involves long and difficult travel, often compounded by financial constraints that make such journeys unaffordable. For example, the primary healthcare clinics are scattered throughout these rural areas. Often, there would be just a single junior assistant doctor, working merely two days a week, tasked with the care of the community. On his limited days at the clinic, he might administer vaccinations, provided, of course, that he had access to fuel for transportation, which was a lifeline for many. Yet, even with these scant services available, the thought of traveling 35 kilometers in a shared taxi from their distant homes was a daunting prospect for most. The barriers were not just logistical; the very systems meant to support these villagers had become entangled in complexity. Both government and non-government initiatives had, in essence, rendered medical help an unaffordable luxury for those who could not shoulder the full financial burden. It was unsurprising, then, when stark statistics emerged: 40% of the local population opted against seeking medical assistance, even when their need was palpable. In these quiet rural settings, the struggle for basic healthcare transformed into a narrative of longing, hope, and resignation [18].

3.3. Healthcare Personnel

Several factors have been found to impact healthcare staff in rural areas, such as low nurse-physician ratios, lack of rural incentives, and temporary staffing. There exists a significant deficiency in the availability of doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals necessary to adequately address the healthcare requirements of Jordanians residing in rural regions. The nurse-to-physician ratios in Jordan are comparatively lower than those observed in other areas. Currently, approximately 20% of the active physician workforce is not practicing medicine, highlighting migration, retirement, administrative roles, and a lack of job opportunities in underserved areas [19]. Among Jordanian physicians, 81.9% are specialists, while 18.1% are either interns or general practitioners, as they have yet to complete their specialized training. The private sector employs the majority of midwives and dentists. According to the Ministry of Health (2023), there are 3.16 physicians, 2 pharmacists, and 2.8 registered nurses per 1,000 citizens, which is inadequate and may affect the care provided.

Moreover, various other factors contribute to the difficulty in attracting and retaining healthcare providers in rural settings. These factors include the influence of family, the need to sacrifice and/or alter relationships with other healthcare workers, the performance of doctor colleagues and hospital consultants, job insecurity resulting from changes, the hierarchy of colleagues, and local practice issues. Data reveal that few healthcare personnel live in the communities they are serving and that many of those who provide services are frequent visitors who do not stay overnight. Half of the primary healthcare center teams lack personnel with practical skills and up-to-date, safe medical practices. The nurse-to-physician ratio in primary healthcare equals 1.1 nurses per physician [20].

A significant shortfall in workforce development markedly impacts the effectiveness of service delivery [21]. The primary challenge resides in the difficulty of providing professional development. Thus, the opportunities for healthcare practitioners in rural and underserved areas [22] may, in turn, enhance their commitment to these communities. Given the expanding realm of medical tourism, which refers to individuals from neighboring countries or from within Jordan traveling to urban centers or private institutions for specialized care, which can divert resources from public healthcare and exacerbate disparities in rural areas [23], it is essential for the Ministry of Health to thoroughly evaluate the qualifications of healthcare professionals to guarantee the sustainability of effective service delivery in rural settings. Although the Ministry offers scholarships to individuals from rural backgrounds, it unfortunately fails to provide the necessary time off that would facilitate access to professional development opportunities. Therefore, the establishment of continuing professional development (CPD) is instrumental in improving workforce skills, fostering staff retention, and increasing job satisfaction, thus positively impacting service delivery outcomes [24]. According to an earlier study [25], continuous professional growth equips healthcare practitioners to deliver high-quality services that meet the unique needs of the community. A strong dedication to cultivating a workforce focused on exceptional, patient-centered care not only encourages innovation but also strengthens the healthcare system's capacity to adeptly address the complexities of modern practice.

Multiple stakeholders, including the MoH, healthcare policymakers, local governments, and professional bodies, are responsible for the change in the healthcare system. Additionally, interdisciplinary collaboration among these entities is crucial for effective and sustainable improvements.

3.4. Barriers to Accessing Healthcare in Rural Jordan

Several barriers still hinder rural healthcare access in Jordan. Geographical barriers are one of the first layers that impede rural residents' access to healthcare [23]. As many healthcare facilities are in or near cities, where a significant portion of Jordanians live, the rural population seeking care simply has fewer options. This geographic constraint forces rural residents to walk long distances to facilities or use other modes of transportation. The second layer of barrier to healthcare access in rural Jordan concerns the financial aspect [26]. Long trips to seek care cost money, consume time, and sometimes result in lost workdays. Additionally, rural individuals typically bear the full cost of medical care when they visit a doctor or purchase prescribed medication. The financial costs of seeking and acquiring healthcare can ultimately lead families to decide against seeking necessary medical care [27]. Researchers estimate that the elevated costs associated with healthcare services cause a significant proportion of individuals to delay or abstain from pursuing them.

Access to healthcare is a fundamental human right, yet a multitude of individuals suffer and even die from treatable conditions because they are not able to gain access to necessary care. Geographical and financial barriers combined work against rural residents in Jordan, contributing to worse health outcomes in such areas compared to their urban counterparts. In conversations with rural Jordanians, they mentioned several reasons for these delays in seeking care and forgoing healthcare. The most prominently discussed barrier was the high transportation costs necessary to reach distant facilities. A thirty-nine-year-old Jordanian widow stated, “I can’t afford the transportation from my isolated village to the nearest public health center... I request assistance from someone to drive me there, but he deducts the cost of the trip from my family's budget.”

A major source of healthcare delays or postponement was financial constraints. An unemployed rural man revealed that he opted not to seek treatment for his leg pain, citing the transportation cost as the biggest obstacle: “I am experiencing a crisis due to my inability to afford treatment.”

In addition, various other barriers, including geographical isolation, inadequate infrastructure, and a shortage of qualified medical professionals, hindered access to healthcare in rural Jordan.

3.5. Geographical Challenges

Physical geography creates major barriers to healthcare access for patients in rural Jordan [28]. Most villages are located on hills and mountains, and they are separated by several kilometers of unpaved roads from access to the secondary healthcare system and larger public hospitals. The public and private sectors at the sub-district and district levels house additional facilities that offer basic primary care. These facilities provide general outpatient care, basic diagnostic and laboratory services, preventive services, and some curative care. In areas of very low density, such as eastern Jordan, with a density of less than 7 people per km2, the distance between villages can be 40-50 km [29]. Consequently, sub-district facilities offer minimal medical services, typically provided by contracted doctors for only two days a week at most. This reality of physical inaccessibility to health facilities and tertiary care may result in the non-provision of timely health interventions that could save lives and reduce morbidity [22].

Also, patients struggle to reach nearby hospitals due to a lack of private cars and inadequate public transportation. Buses only reach the village center, leaving patients to walk to the upper parts of the village. Men typically reserve direct hospital transport, which presents additional challenges for women. During busy seasons, like harvests or adverse weather, these service vehicles are even scarcer, pushing many women towards indigenous treatments instead of seeking formal healthcare [30]. This reliance on alternative care can adversely affect morbidity and mortality rates from preventable conditions. Areas with fewer physicians and lower per capita income tend to have higher mortality rates. Geographic isolation also hinders access to emergency services, including maternal healthcare [31]. To address these issues, it is crucial to engage communities in recognizing and advocating for maternal health facilities near them. Supplementary first-aid training for midwives and nurses in these remote areas can be valuable, ensuring emergency hospital transfers for complex cases [32]. Consequently, enhancing access to healthcare must account for Jordan’s geographic conditions, which may require tailored planning and service delivery mechanisms due to the physical isolation of rural populations.

3.6. Financial Constraints

When discussing the ability to access healthcare services, financial access is a more prominent issue in Jordan [33] compared to other dimensions, such as the physical and organizational aspects of care. The cost and burden associated with accessing healthcare stand as barriers that often lead patients to avoid or delay necessary services [34]. Residents in rural areas who require specialized healthcare treatment face additional financial challenges due to the cost of travel, housing, and meals during such treatments. Low-income Jordanians and those with a lower ability to work because of illness or injury are more likely to live in rural areas, thereby exacerbating the vicious cycle of health and limited ability to work. Many found it difficult to afford the cost of healthcare in Jordan. Despite the mandatory health insurance for the vast majority of Jordan's population, Jordanians incur out-of-pocket expenses equivalent to around 30% of their gross income [35, 36]. This percentage does not account for transportation to healthcare facilities or lost income.

Residents in Jordan, particularly those living in rural areas, identified financial constraints as the primary challenge to accessing healthcare [37]. Similarly, the long-term effects of healthcare payments can lead to economic hardships or the need to sell properties or goods. Furthermore, when families face economic hardships due to health, they have been shown to rely on biological family networks and communities for both economic and non-economic forms of support. Jordan could have a safety net for healthcare costs, supported by both government and non-governmental sources [38, 39]. Governmental support may take the form of aid, a reduction in the full cost of procedures for the most extreme medical cases when the individuals exhaust their insurance, or non-cash financial support through loans.

On the other hand, one of the biggest obstacles to receiving healthcare in rural Jordan is transportation. The problem is made worse by inadequate public transportation, long commutes to facilities, and inadequate infrastructure [40]. Due to dirt roads, expensive transportation, and irregular bus services, many rural inhabitants, particularly those living in isolated locations, have difficulty getting to hospitals or clinics [41]. For instance, patients may have to drive for hours to get to the closest hospital in places, like Ma'an or the Jordan Valley, frequently using pricey private taxis or erratic public transportation.

3.7. Intersecting Barriers

In Jordan's rural areas, several interconnected constraints affect access to healthcare. Low-income women frequently face dual disadvantages: financial limitations and constrictive gender norms that restrict their mobility or necessitate male company. These interrelated issues exacerbate care delays and lead to poorer health outcomes when combined with remote locations and limited clinic resources. For instance, women who lack access to transportation may put off getting treatment for long-term illnesses, and their lack of financial independence makes it more difficult for them to afford necessary services or prescription drugs. This intersectional disadvantage underscores the need for comprehensive policy responses that address both social determinants of health and structural constraints.

3.8. Innovative Solutions to Improve Access

Given the challenges facing healthcare access and utilization in rural Jordan, several solutions have been proposed and implemented by various non-governmental sectors working in the country. Community-based programs have offered medication delivery to address the health service barriers faced by homebound groups [42]. Projects have created fully equipped mobile clinics, including laboratory services, to provide primary health care services directly to people rather than expecting them to travel long distances. Importantly, efforts have increasingly turned to developing, implementing, and mainstreaming technology and delivery, such as telemedicine and mobile health clinics.

Currently, the focus is on assisting vulnerable Jordanians and refugees living in refugee camps. We regard telemedicine and e-prescriptions as progressive solutions to address several of the previously mentioned obstacles, including inadequate privacy, women's tendency to stay at home, geographical remoteness, and transportation costs.

A recent exploration into healthcare delivery revealed promising advancements in patient access, particularly through projects that reach beyond temporary camps. In northern Jordan, mobile ophthalmology services have significantly enhanced access to care, thanks to the synergy between healthcare providers and community organizations. This integration of telemedicine has paved the way for lasting healthcare solutions, effectively reaching underserved populations [43]. These initiatives contribute to a more efficient and equitable national health system in the provision of services. Through robust monitoring and evaluation, valuable insights can be gleaned for future similar endeavors, fostering increased collaboration and alignment with the national health framework. The analysis has further revealed that telemedicine holds substantial potential for delivering sustainable health services, proving to be both acceptable and effective for patients and healthcare professionals alike. The urgency for specialty care among vulnerable populations cannot be overstated, which is why the Ministry of Health has prioritized these services, ensuring there is no redundancy [44, 45]. Table 2 provides a summary of innovative solutions for rural healthcare access.

| Innovation | Key Features | Benefits | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile health units | On-site care delivery to remote areas | Improves physical access; flexible services | High cost; limited coverage radius |

| Telemedicine | Digital consultations via video or phone | Reduces travel needs; improves access to specialists | Connectivity gaps, regulatory and training needs |

| Community health workers | Local peer support for health promotion and referrals | Builds trust; culturally sensitive outreach | Variable training, low professional status |

3.9. Telemedicine and Mobile Health Clinics

According to Haleem, et al. [46], telemedicine refers to the provision of healthcare services through information and communication technology (ICT), enabling the delivery of medical care services from a distance and the digital delivery of medical advice within the normal doctor-patient relationship. In the context of a shortage of physicians in rural Jordan, telemedicine provides a “virtual” channel for bridging the gap between patients in rural Jordan and international healthcare providers. Areas, like Al-Mafraq, which has 650,000 inhabitants and is served by seven hospitals, including four governmental hospitals, one private hospital (Al-Noor Hospital), and King Talal Military Hospital (Ministry of Interior of Jordan, 2024), could benefit from telemedicine, allowing medical teams to receive advice from experts in the cities. Indeed, mobile clinics could provide primary healthcare services, such as primary medical care, dental services, and well-baby services, to people living in remote areas or those who are difficult to reach. Mobile units, integrated into primary healthcare, help connect individuals to additional free secondary services offered by government and private clinics.

The traditional approach to medical care delivery relies on various health facilities, sufficient infrastructure, qualified manpower, and the community's ability to access those facilities and the healthcare providers who work there. People living on the outskirts of the city or in rural areas and nomads typically lack access to essential services. As a result, they are more prone to diseases and injuries. The use of technology to improve patient outcomes in clinically coordinated communities is thus increasing. Information and telecommunications technology and various applications are being used to improve access to specialist consultations and follow-up care, standardize care, and provide cost-effective ways to reach underserved populations, especially in rural communities.

Revenue is not the primary solution for these kinds of models because it is part of a private organization's corporate social responsibility and a non-profit organization's vision. For the successful implementation of telemedicine or mobile clinic centers in rural communities, infrastructure at the backend needs to be present, which usually includes internet facilities. The people in the rural community should be trained in various physical procedures to support the required manual check-up. This could help reduce the chances of misdiagnosis. A study on the initiatives and on auditing the effectiveness of operations at the registered healthcare center could be conducted to determine how many people can benefit from the center's services in a year and the outcomes of the treatments. If possible, a case study or several case studies can be carried out on individuals living in rural communities far from cities who do not have access to proper care for at least a year, evaluating their health outcomes after receiving services and comparing their pre- and post-treatment health outcomes. Public health and preventive care can mainly benefit from this model.

3.10. Community Health Workers

Community health workers (CHWs) are becoming increasingly valuable in many rural areas worldwide. In the MENA region, CHWs have proven effective in the adaptation of healthcare for Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon [47], as well as in Afghanistan and Pakistan [48]. Rural Jordan, like other parts of the world, requires an essential link between healthcare systems and the communities they serve. One of the strengths of such a model, centered on community health workers, is that an initiative combining elements of healthcare and health system capabilities could naturally leverage this established level of trust and foster community participation.

Though often unpaid and hourly-based, CHWs are from various districts, providing advantages to both systems and patients [49]. Their deep knowledge and connections enable them to offer a wide range of care. By equipping CHWs with tools for preventative care and health education, providers can enhance health outcomes [50, 51]. In rural areas, CHWs tackle cultural beliefs about healthcare and improve health literacy. Being from various communities they serve helps bridge cultural divides. The scalability of existing CHW-led projects could extend policies that address both healthcare and health system barriers, thereby improving care practices.

The data demonstrate the significant impact CHWs' voluntary time can have on the lives of those they assist. We can shape many of these stories into successful narratives by sharing the experiences of both the CHW and the benefactors [52]. This centering of the community and sharing experiences can allow the beneficiaries to advocate for new community members to get involved and educate them on how to access services and where they may be relevant [53]. Furthermore, these existing partnerships can contribute to the data demonstrating the success of community health workers (CHWs), as well as the extensive rights and nontraditional services they provide.

In the rural areas of Jordan, community health workers (CHWs) have taken on a vital and increasingly important role in effectively bridging the significant gap that often exists between essential healthcare services and underserved populations. These dedicated individuals work diligently to tackle both accessibility and awareness issues that frequently affect these communities, ensuring that a larger number of individuals receive the critical care they need. By going door to door, providing valuable health education, and facilitating access to important health services, CHWs play an essential role in improving the overall health outcomes of their communities.

Besides, nursing programs should prepare nurses to work effectively in rural settings, equipping them with skills in community health, telehealth, and culturally competent care. Programs should also advocate for rural clinical placements and incentivize rural service post-graduation.

4. DISCUSSION

The review highlights that nurses in rural Jordan face significant challenges in delivering healthcare, including limited resources, geographical barriers, and a shortage of trained professionals, which exacerbate health disparities in these underserved areas. The scarcity of medical facilities and equipment, coupled with long travel distances, hinders timely access to care, particularly for chronic and emergency conditions. This finding has been consistent with a systematic review performed earlier [54], which stated that enhancing patient access to the community system while expanding the availability of skilled physicians and transportation should be the main goals of policymakers and researchers working to improve community care in rural areas and low- and low-middle-income nations.

Furthermore, nurses often lack adequate training opportunities and face cultural barriers, such as gender norms, which can impede effective patient interactions. This finding has been found to be in line with previous studies [55], which have highlighted barriers and factors that affect nursing communication as well as the cultural barriers, and emphasized how different elements affect how well nurses and patients communicate; this stresses how important it is for nurses to improve their communication skills and get proper training from nursing professionals.

Innovative solutions, such as mobile health clinics and telemedicine platforms, have shown promise in bridging these gaps by bringing services directly to remote communities and leveraging technology to connect patients with specialists. Community health worker programs, supported by training and integration into formal healthcare systems, also enhance outreach and education, addressing cultural sensitivities. These findings align with studies performed earlier [56, 57], emphasizing the need for scalable, technology-driven interventions to improve healthcare access in resource-constrained settings. However, sustained investment and policy support are critical to ensure these solutions are equitable and sustainable, particularly to address systemic issues, like workforce retention and infrastructure development, in rural Jordan.

5. LIMITATIONS

This review has been constrained by its reliance on a small number of studies, which may not have adequately reflected the range of difficulties nurses encounter in Jordan's rural areas. The scope has been limited by the availability of recent, peer-reviewed literature, which might have caused it to miss local or unpublished reports that might have offered further information. Additionally, the assessment has largely concentrated on problems and solutions unique to nurses, which may underrepresent the viewpoints of other medical professionals or patients. Regional differences in Jordan's healthcare regulations, cultural customs, and infrastructure may limit the generalizability of the findings. Lastly, the review has relied on secondary sources rather than primary data analysis, which could have introduced biases or gaps in existing knowledge.

CONCLUSION

This review has examined the pervasive structural and systemic inequities that contribute to inadequate healthcare access in rural Jordan, highlighting the urgent need for innovative and sustainable solutions to address these multifaceted challenges. Key barriers have been observed to include prohibitively high healthcare costs, chronic shortages of qualified medical personnel, and limited education and awareness about the critical role of early intervention and preventive healthcare. Additionally, rural populations are faced with poorly equipped and geographically inaccessible health facilities, compounded by gendered cultural practices that restrict care, particularly for women. The lingering effects of war and conflict-related trauma, alongside environmental risk factors, such as water scarcity and extreme heat, further exacerbate health disparities in these communities. These interconnected challenges demand a comprehensive and nuanced analysis of the rural population’s needs to inform dynamic, evidence-based policies that address intersectional inequalities, particularly in the northern regions and the Jordan Valley. To achieve meaningful health improvements, the research advocates for strengthening Jordan’s national health system through innovative, inclusive, and community-driven strategies. This vision requires robust collaboration among civil society, government institutions, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and rural communities at every stage of the process, from identifying critical challenges to co-designing tailored solutions, implementing programs, and evaluating outcomes. Such a participatory approach can ensure transparency, foster accountability, and place the needs and rights of marginalized groups at the heart of policy development. By addressing systemic disparities through improving geographic equity in the allocation of health resources and providing culturally sensitive and sustainable interventions, such as mobile health clinics, telehealth services, and community health education programs, stakeholders can enhance universal healthcare access and equity. Furthermore, integrating local knowledge and prioritizing community engagement can ensure that solutions are not only effective but also resilient, empowering rural Jordanians to achieve better health outcomes and fostering long-term systemic change.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: A.A.: Study conception and design; S.B.H.: Writing of the paper; A.M.E.: Writing, review, and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ICT | = Information and Communication Technology |

| CHWs | = Community Health Workers |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.