All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Effect of Self-management Intervention on Improvement of Quality of Life in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Background

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) presents significant challenges globally, affecting health-related outcomes, quality of life (QoL), and healthcare expenditure. Self-management interventions are currently gaining importance as a means to empower the patients to manage their disease by themselves. However, currently there is a paucity of evidence evaluating its overall and proven role in patients with CKD. With this goal, we have designed this review to have a consensus on this aspect.

Objective

The objective of this study is to determine the effect of self-management interventions among patients with CKD who are not on renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Methods

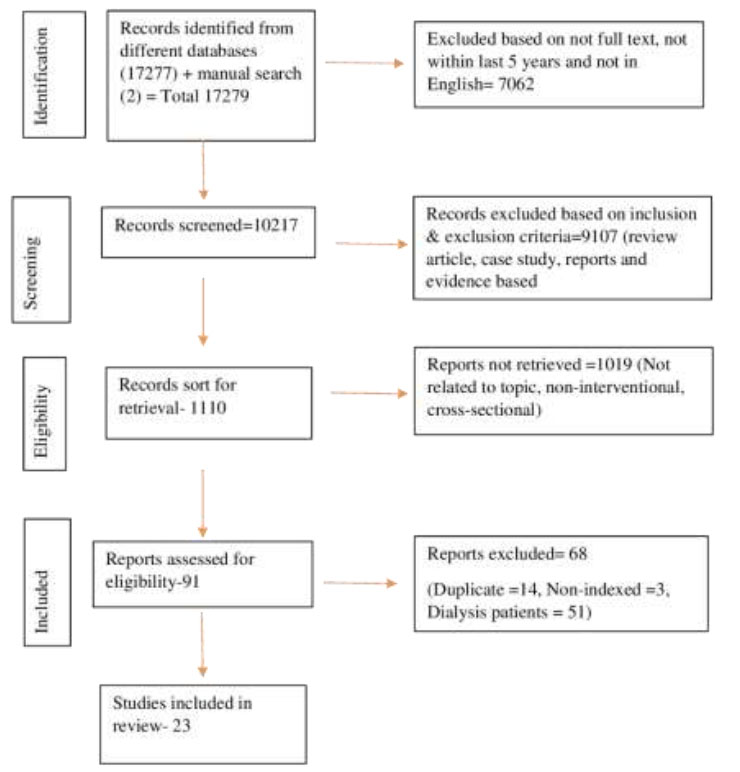

This review was performed complying with the guideline set by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). Literature search was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, and ProQuest databases using the keywords “Chronic Kidney Disease”, “self-management intervention” and “Quality of Life”. Articles on patients with CKD not requiring RRT, published between January 2018 and December 2023, were included in this review. Articles such as dissertations, review articles, non-interventional studies, and those written in languages other than English were excluded. Out of the initially screened 17, 279 studies, 23 studies (including 3, 345 patients aged between 18 and 81 years) fulfilled our inclusion criteria were finally included in this review. Quality assessment and data extraction were conducted using Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) and Mixed Method Appraisal tool (MMAT).

Results

Overall use of self-management interventions led to improvements in diet quality, psychological health, Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), self-management behaviors, and physiological and biochemical markers in patients with CKD. Nurse-led interventions, multidisciplinary approaches, and virtual care were found to be effective in enhancing self-efficacy and QoL.

Conclusion

Self-management interventions can significantly improve various aspects of health and QoL in CKD patients. Nurse-led and multidisciplinary approaches, as well as virtual care, are found to be effective strategies in this subset of patients who do not require RRT. Further research is needed to emphasize evidence and refine the interventions for broader application.

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) poses substantial challenges to both patients, physicians, and healthcare systems globally,which culminates in poorer health outcomes, reduced quality of life (QoL), and significantly higher healthcare expenditure [1]. The burden of CKD is compounded by its frequent co-association with other concurrent medical conditions such as diabetes, cardio- vascular disease, and depression [2]. Managing patients with CKD involves judicious balancing between medical management and basic requirements to deal with daily life and the accompanying emotional and psychosocial impli- cations of living with such a chronic progressive as well as virtually incurable disease [3]. Self-management inter- ventions have recently emerged as a promising option for enhancing managing patients with CKD by empowering the patients to take an active part in managing their health condition and associated co-morbidities [4]. Self-management intervention includes any type of inter- vention such as nutritional intervention, education on self-management, counseling, and exercise. These inter- ventions are used with the aim to prevent further progression of CKD to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) by improving knowledge, skills, and confidence in self-management of medical aspects, facilitating access to resources, and coping with the emotional burden of the illness [5]. All stakeholders, patients, caregivers, clini- cians, and policymakers, have felt the need to develop effective strategies that empower patients with CKD to manage their own disease and co-morbidities [5]. Despite the escalating prevalence of CKD and its adverse impacts on outcomes, evidence related to the efficacy of self-management interventions remains limited [6]. As CKD affects millions globally, there is an urgent need to evaluate the real value of self-management strategies as it is cost-effective [7]. Self-management of a chronic disease encompasses self-care behaviors such as self-monitoring, symptom management and other related practices [8]. A self-management program focuses on behavior modi- fication, with the aim of delaying disease progression and improving health status [9]. These strategies empower patients to take an active role in managing their disease conditions, potentially improving their QoL and clinical outcomes. By systematically evaluating and synthesizing existing studies on self-management interventions in patients with CKD, this review seeks to provide a clear understanding of their efficacy to guide clinical practices and research initiatives. This review aims to investigate the intricacies of self-management interventions in patients with CKD by analyzing various studies which employed quantitative, qualitative or mixed methodo- logies. Additionally, this review seeks to elucidate the effects of self-management on disease outcomes, providing a comprehensive understanding of its efficacy and identifying key factors that contribute to successful, positive outcomes.

2. METHODS

This scoping review was done following the guidelines as per the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) checklist [10].

Multiple databases (such as PubMed, Scopus, and ProQuest) were searched using keywords or MeSH (Chronic Kidney Disease or CKD) and (Self-management) and (Quality of Life). The filters such as source type (scholarly journal), publication date (January 2018 to December 2023), document type (original article), and language (English only) were used to narrow down as well as refine the search. Only peer-reviewed articles having full texts were selected. The first two authors (S.P. and S.L.P.) screened all articles initially to find their relevance to the set objectives. Self-management, self-efficacy, quality of life (QoL), improvement of physiological symptoms, and reduction of psychological burden were looked for during the scrutiny of the selected articles. The remaining two authors (F.M.S. and S.P.) reviewed selected articles for their accuracy. Studies were included if the patient population included patients with CKD who were not receiving renal replacement therapy (RRT).

On a preliminary search, 17277 studies related to our selected criteria were found. Another two studies are obtained by manual searching. Out of these, 7062 articles were excluded because of not having full-text or they were published before 2018. Out of the remaining 10217 articles, 9107 articles were excluded based on our inclusion and exclusion criteria. On filtering, a further 1019 articles were excluded owing to their study design and being unrelated to our topic of interest. From the remaining 91 articles, we sought the relevance to our topic. At this step, a further 68 articles were excluded, out of which 14 were duplicates, three were non-indexed, and in another 51 articles, patients did receive RRT. Finally, 23 studies were included in this review. S.P. and S.L.P examined the selected studies to extract data in Population, Intervention, Comparators and Outcomes (PICO) format [11]. F.M.S and S.P. manually checked the included studies for methodological soundness and the effects of interventions. The first and the last authors (S.P. and S.P.) assessed the included studies independently using Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist (randomized control study, cohort or qualitative study checklist) [12-14]. They also assessed the mixed method studies by using Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [15]. Subsequently, the second and the third authors (S.L.P. and F.M.S.) checked both processes to minimize error and further reduce the methodological bias.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were considered eligible if they reported the use of any self-management intervention in their patients. Participants were those with all stages of CKD, excluding those who had received dialysis or renal transplants. Outcomes of the study included improvement in quality of life (QoL), blood sugar, or any other biochemical parameters. Only full-text original articles in the English language were included in this review.

Moreover, the authors excluded evidence-based health care, dissertation/thesis, literature review, case study, field reports, general information, conference pro- ceedings, and commentary articles.

The authors examined the included studies thoroughly to assess the quality of evidence by using the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses Levels of Evidence [16]. Level A includes a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies or meta-analysis of quantitative studies, and level B includes well-designed controlled studies (randomized or non-randomized) with results which consistently support a specific action, intervention, or treatment. Level C includes qualitative studies, descriptive studies, systematic reviews or randomized trials with inconsistent results. Level D includes peer-reviewed professional and organizational standards with support from clinical study recommendations. Level M includes manufacturers’ recommendations only. Considering the nature of the included studies in the present review, only levels B and C were applicable.

Prisma flow chart.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search Results

Out of the initial 17279 studies, the author selected only 23 full-text studies based on the criteria mentioned (Fig. 1).

In this review, the authors examined each article to determine the intervention and outcomes. The types of interventions were identified and classified under different categories.

Across 23 studies, a total of 3345 CKD patients were deemed eligible and considered as a sample (Table 1). The age range of the sample was 18 to 81 years, with an average age of 54.1 years. The analyzed data from these studies are presented in Table 1. The outcomes observed in these studies were dietary practices, knowledge about the disease, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), physiological and biochemical markers, psychological changes, adherence to self-management interventions, and social outcomes.

| S.No. | First Author/Year/ Country/Ref. | Study Design/ Setting | Population/ Sample Size/ Age |

Intervener/Type (topic)/ Mode/Language | Intervention Duration | Evaluation Time Point | Theory or Framework | Result | Level of Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kelly et al, 2020/ Australia [17] | RCT(Pilot)/ not mentioned | CKD 3-4 stage/ n=76/ 62 ± 12 yrs |

Dietician/ Tele health coaching/ Telephone based/English | 2 weeks ⨯ 3 months | 6 months | - | Improvement in dietary practice and body weight. No change in BP or serum electrolytes. Little difference in waist circumference at both time points. No significant difference in quality of life (QoL) at 3 & 6 months. | B |

| 2. | Cardol et al, 2023/ Netherlands [18] | RCT/ four hospitals | CKD patients not on dialysis/ n=121 (eGFR 20-89)/ 56±14.07 yrs |

Therapist Health Psychologist/ Electronic Health Care pathway/ e-mail/Dutch | weekly or biweekly | 3 months | - | The intervention did not improve psychological distress, quality of life (QoL) and self-efficacy. However, it improved the personalized outcomes of functioning and self-management. | B |

| 3. | Havas et al, 2018/ Australia [19] | Pre-post intervention study Single sample/ paricipants’ home or workplace |

CKD, eGFR>25 ml/min/1.73m2,/ n=66/ 55.93 ± 1.85 yrs |

Nurse/ CKD self- management/ Face-to face / English | At week 1 and week 12 | 12 weeks | Social cognitive theory | CKD knowledge, HRQoL, Communication with HCP, intake of fruits & vegetables - all were improved. Alcohol consumption & emotional distress were reduced. |

B |

| 4 | Helou et al, 2020/ Switzerland [20] | RCT crossover study/ Home & Clinic | Diabetic kidney disease/ n=32/67.8 ± 10.8 yrs |

Nurse/ Multidisciplinary approach/ face-to-face and telephone-based / English | every 2 weeks for 3 months | 6 months | Self-care deficit nursing theory | Improved quality of life (QoL) and self-care activities such as dietary habits & blood sugar testing. | B |

| 5 | Hu et al, 2022/ China [21] | Quasi experimental/ CKD Clinic & Hospital | CKD/ n=120/ 56 ± 19.58 yrs | Nurse/ “Nurse led ward Home” outpatient/ Face to face /English | Follow up at D3, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 8 weeks and 12 weeks | 12 weeks | - | Negative emotions, sleep disorders, self-management ability and quality of life (QoL) were improved. The disease process slowed down to a certain extent. | B |

| 6 | Humalda et al, 2020/ Netherland [22] | RCT/ Hospital | CKD stage 1-4/ n=99 (eGFR≥25 ml/min/ 1.73 m2) /56.6 ± 12.4yrs |

Dietitians, lifestyle coaches, or research nurses/ Web based self-management intervention/ face-to-face/ Dutch | 3 months | 6 months | - | During intervention phase, dietary restriction of sodium was achieved which resulted in decreased sodium excretion and decreased systolic blood pressure. | B |

| 7 | Kyte et al, 2021/ UK [23] | parallel RCT & Qualitative substudy/ Hospital | Advanced CKD/ (eGFR≥ 6 ≤15 ml/min/m2) / n=52/57 yrs |

Dietician/ ePROM intervention/ Electronic & Face to face/ English | 12 months | - | - | Intervention adherence was high beyond 90 days & 180 days but dropped beyond 270 days. Qualitative interviews attest the concept and acceptability of intervention with necessary changes to increase the functionality of ePROM system. | C |

| 8 | Li et al, 2020/ Taiwan [24] | Prospective RCT/ Nephrology Clinic and rural area | CKD stage 1-4/ n=60/ 51.22 ± 10.98 yrs |

Physicians/ Electronic mobile devices (wearable)/ electronic and telephone based/ English | - | 90 days | - | Self-efficacy and self- management were improved. Higher KDQoL and slower decline of eGFR in the intervention group. No differences in body composition between the groups were observed though 90 days of post-intervention, the steps per day was increased. |

B |

| 9 | Lin et al, 2021/ Taiwan [3] | Single centre parallel group RCT/Nephrology Clinic | CKD 1-3 stage/ n=108/ 50 yrs |

Nurse/ Health Coaching & Self-management booklet/ Face to face & telephone based/ Chinese | weekly 1 hr sessions for 4 weeks | 12 weeks | - | Quality of life (QoL), self-management, patient activation and self-efficacy were improved at post-intervention and at 12 weeks follow-up. | B |

| 10 | Nguyen, et al, 2019/ Australia [25] | Parallel group RCT/ Renal clinic | CKD 3-5 stages/ n=135/ 48.9 ± 13.8 yrs |

Nurse/ Self- management Booklet & followed by telephone support/ Face to face / Vietnamese | Week 0: 1 hr face to face Weeks 4, 12: 20/30 mins telephone call |

16 weeks | Social Cognitive Theory | Self-management, knowledge and self-efficacy were increased. Both physical and mental components of HRQoL were improved without any change in systolic or diastolic blood pressure. | B |

| 11 | Ong et al, 2022/ Canada [26] | Qualitative/ Renal Clinic | CKD 4-5 stages/ n=11/ 58 ± 17 yrs |

Physiotherapist/ ODYSSEE Kidney Health, a digital conselling program/ Electronic/ English | 16 sessions | 4 months | - | Satisfactory adherence to self-management interventions for maintaining positive behavioral changes were observed. | C |

| 12 | Ozieh & Egede, 2022/ US [27] |

Pre-post design/ Clinic | CKD stage 1-2/ n=30/56.7 ± 13.5 yrs |

Nurse/ Manualized study intervention/ Telephone based / English | 30 minutes | 6 weeks | Intervention-Motivation Behavioral Skills Model | HbA1C, total cholesterol & eGFR improved. Self- efficacy, CKD-knowledge, practice of exercises and blood sugar testing were increased. | B |

| 13 | Perna et al, 2022/ Kingdom of Baharain [28] | Retrospective cohort study/ Hospital | Predialysis patients/ n=265/ 66.5 ± 13.6 yrs |

Dietician/ Nutritional intervention/ Face to face/ English | monthly intervention | 15 months | - | Blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine were reduced. Positive impact on weight loss & BMI were observed. Lipid profile, mainly total cholesterol, triglyceride levels reduced significantly. Reduced glucose & HbA1C. The intervention group had a significant increase in eGFR. | B |

| 14 | Theeranut et al, 2021/ Thailand [29] | RCT/ Community Hospital | CKD up to stage 3b/ n=344/67.36 ± 11.97 yrs |

Nurse, Pharmacists & Internists/ Multidisciplinary treatment called Chumpae model / Face-to-face and telephone-based/ English | 3 months | Chronic care model | eGFR improved and staging improved by one stage with intervention. | B | |

| 15 | Vasilica, et al, 2020/ UK [30] | Longitudinal, mixed method study, two phases- 1)design & training 2) longitudinal evaluation/ Social media platform |

CKD patients & carer n=15 for codesign n=50 for training n=18(17 pts+1 carer) for evaluation/44.85 ± 3.32yrs |

Nurse/ Co-designed social media intervention/ online / English | weekly logs, qualitative interview at 0,6 months |

6 months | - | The intervention led to increased self-efficacy and self-care. Moreover, there was improved health management and better outcomes in terms of employment and social capital. | B |

| 16 | Zhou, 2022/ China [31] | RCT/ Nephrology Clinic | CKD/ n=100/48yrs |

Nurse/ Nursing intervention/ Face to face/ English | 6 months | 6 months | - | The images were clearer post-intervention. The self-management ability and the quality of life (QoL) in the experimental group was greater than control group. The corresponding magnetic resonance apparent diffusion coefficient and fractional anisotropy in the cortex were greater than those in the control group. The serum creatinine & 24 hours urinary protein were lower than the control group. | B |

| 17 | Zimbudzi et al, 2020/ Australia [32] | Longitudinal study/ Clinic | CKD stage 3a or worse/ n=179/ 64.8 ± 11.1yrs |

Research team (Endocrinologist.Nephrologist,Nurse practitioner, Dietician, Administrator, Research officer)/ Integrated diabetes & kidney disease model/ face to face/ English | 12 months | - | Physical composite scores considerably improved in women while the score slightly deteriorated in men. Patients with stage 5 CKD experienced a greater improvement in physical scores as well as in mental composite scores compared with those having mild kidney disease. | B | |

| 18 | Kristina, et al, 2022/Indonesia [9] | Quasi experimental study/ Village | CKD/n=39/61.4 yrs | Nurse/ CKD Intervention group-24 & control group-1-5/ Face to face/ English |

2 weeks | 2 weeks | - | Levels of knowledge and self-regulation increased significantly (66% and 70%, respectively). Uric acid and cholesterol levels decreased considerably. Blood protein levels remain unaltered. | B |

| 19. | Wu et al, 2018/ Taiwan [8] | RCT Single- blind randomly assigned/ Nephrology Department |

Pre ESRD patients/ n=112/ 70.16 ± 11.6yrs |

Nurse/ Innovative self-management program/ Face to face and telephone interviews/ Mandarin & Taiwanese | 4 weeks | 3 months | Self-Efficacy theory | The physiological indicators (BUN, creatinine) and the psychological indicators (depression, self-efficacy & self-management) showed considerable improvement. | B |

| 20 | Wani and Koul, 2019/ India [33] | Quasi experimental non equivalent two group pre test and post test design/ Nephrology ward | CKD patients/ n=200/44.95 ± 0.31yrs |

Dietician and Nurse/ Renal Diet Therapy and Deep Breathing Exercises/ Face to face/ English | Exercises demonstrated for 5 minutes each twice a day. Renal diet therapy by dietician was given after every 24 hours. | 6th day, 15th day | - | Fasting blood glucose, lipid profiles, serum electrolytes, hematocrit and platelets improved significantly in intervention group. | B |

| 21 | Watanabe et al, 2022/ Japan [34] | Follow up study with Experimental & Control group/ Outpatient department | Type 2 diabetes with CKD 3-4 stages/ n=159/ 68.16 ± 6.87yrs | Nurse/Self-management education program/Telephone based & face to face/ English | Face to face every 2 wks⨯ 2 months, Over telephone monthly⨯ 3 rd to 6th months | 6 months | - | The intervention group had a lower incidence of diabetic nephropathy and decreased need for emergency care compared with control group. | B |

| 22 | Ibrahim & Miky, 2019/ Egypt [35] | Quasi experimental study/ Diabetes clinic | CKD stage 1-3/ n=96/ 24 ± 14.7yrs |

Nurse/ Self-management educational program, Educational booklet, group discussion/ Group | 4 days/ week | 5 months | - | Knowledge scores at post-program implementation were considerably higher, compared to pre-program scores. | B |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | After the program implementation, the patients were found to adapt to healthy practices better compared with pre-implementation | - |

| 23 | Shobha, et al, 2023/ India [36] | Pre-experimental design/ Hospital | CKD n=50/ 46.2±4.42 yrs |

Nurse/ Nurse-Led Educational Intervention/ Face to face/ Kannada | 45 minutes | 8th day | - | Patients’ knowledge increased adequately. | B |

3.2. Characteristics of Studies

The most common (78%) study designs are experimental (18 out of 23). The remainder include observational studies (prospective and retrospective cohort), qualitative studies, and mixed method approaches (Table 2). The majority of studies (59%) are from Australia, Taiwan, Netherlands, China, India and UK (Table 1). Most of the studies (18 out of 23, 78%) were published in the last 4 years (Table 1).

3.3. Description of Interventions

The most common language of intervention was English (70%) as shown in Table 3. Nurses and a nurse-led team provided most of the interventions (70%), followed by dieticians (13%) and other healthcare professionals. Self-management programs, multidisciplinary interventions and web-based health management constituted the majority (65%) of the interventions, followed by dietary and nursing interventions, which comprised of 13% each. In this review, the most common intervention mode was ‘face-to-face’ either alone (43%) or combined (30%) with other modes. Electronic and telephone-based interventions were found in about 26% of the studies. The duration of interventions and evaluation time points were not available in some studies.

| Broad Categories | Sub-heading of Broad Categories | Types of Research Designs | Number of Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Experimental | True-experimental | 13 |

| Quasi-experimental | 4 | ||

| Pre-experimental (Pre-test--post-test) | 1 | ||

| Observational | Prospective cohort | 1 | |

| Retrospective cohort | 1 | ||

| Qualitative | 1 | ||

| Mixed method | 2 | ||

| Types of Interveners | Number | Language Used | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse | 13 | English | 16 |

| Nurse-led team | 3 | Dutch | 2 |

| Dietician | 3 | Chinese | 1 |

| Therapist, Health Psychologist | 1 | Arabic | 1 |

| Physician | 1 | Vietnamese | 1 |

| Nurse & Dietician | 1 | Taiwanese | 1 |

| Physiotherapist | 1 | Kannada | 1 |

| Types of Intervention | Number | Modes of Intervention | Number |

| Self-management program | 5 | Face-to-face | 10 |

| Multidisciplinary | 5 | Face-to-face and telephone-based | 6 |

| Web-based health management | 5 | Face-to-face and electronic-based | 1 |

| Diet/Nutrition | 3 | Telephone-based | 1 |

| Nursing intervention | 3 | Telephone and electronic-based | 1 |

| Cognitive-behavior therapy | 2 | Electronic-based | 4 |

| Number = number of studies where the said parameters are found | |||

Most of the studies did not report the use of any theory or model. Only six studies (26%) employed any theoretical framework or model. The theories/models used include social cognitive theory, self-care deficit nursing theory, intervention motivation behavioral skill model, chronic care model and self-efficacy theory (Table 1).

3.4. Synthesis of Results

Self-management interventions were found effective in various aspects such as diet quality, psychological health, HRQoL, self-management, self-efficacy, physiological markers, biochemical markers, adherence to self-manage- ment interventions, achieving behavioral changes, know- ledge and education, and social outcomes.

3.4.1. Diet Quality and Nutritional Intake

Telehealth interventions led to significant short-term improvements in diet quality, including increased vegetable intake and dietary fiber, although these changes were not sustained beyond 3 months [17]. Notable reductions were observed in fasting glucose, HDL cholesterol, phosphorus, potassium, total cholesterol, triglyceride, and LDL cholesterol, with increases in calcium, chloride, hematocrit, and platelets, indicating improved nutritional management [33]. Restricted sodium intake resulted in lower systolic blood pressure [35].

3.4.2. Psychological Health and HRQoL

The application of person-centered self-management interventions yielded small to medium improvements in self-efficacy and HRQoL, as well as reductions in psychological distress [19]. Likewise, multidisciplinary interventions resulted in improvements in specific dimensions of QoL, self-care activities, and psychological functions [20]. Similarly, the nurse-led “outpatient-ward-home management model”, implemented during discharge from the hospital, considerably enhanced psychological function compared to the control group [21]. However, there were no significant effects on psychological distress or HRQoL following the application of therapist guided “internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy with self-management support” [18]. The “patient-centered coordinated multidisciplinary management” approach improved self-management, communication, and coordi- nation of care, thereby finally enhancing both physical and mental composite scores in CKD stage 5 patients [32].

3.4.3. Self-Management and Self-efficacy

The application of self-management interventions led to significant improvements in both self-efficacy and self-management behaviors [19, 3, 25, 30]. Additionally, post-intervention knowledge about kidney disease increased among patients [25, 35, 36]. These interventions also resulted in the improvement of QoL for the patients [3].

3.4.4. Physiological and Biochemical Markers

The application of a nurse-led “outpatient-ward-home management model” resulted in reduced serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, along with better maintenance of body mass index, prealbumin and albumin levels in the experimental group [21]. The use of a mobile health app led to higher eGFR and increased physical activity in the intervention group [24]. Personalised care with dietary advice by an expert renal dietician considerably improved eGFR, reduced serum creatinine levels, and enhanced nutrition-related biomarkers [28]. Theeranut et al. [29] reported an increase in eGFR and an improvement in disease staging by one stage with the application of multidisciplinary treatment model. Another study [31] reported similar improvements in serum creatinine and urinary protein levels in the experimental group using “face-to-face nursing intervention”.

3.4.5. Adherence to Interventions and Behavioral Changes

The application of a lifestyle intervention led to positive behavioral changes and satisfactory adherence to self-management interventions [27]. Similarly, the use of an “electronic patient-reported outcome measure” demon-

strated high adherence to the intervention, which remained elevated even up to 180 days [23]. After a disease management intervention, the incidence of diabetic nephropathy and the need for emergency care were reduced in the treatment group [34]. The implemen-

tation of a “digital kidney health-counseling” program resulted in a satisfactory adherence to self-management behavior among patients [26].

3.4.6. Knowledge and Education

Application of a self-management program resulted in a considerable increase in knowledge, improved self-regulation and favourable biochemical markers [9].

3.4.7. Social Outcomes

Use of a “patient-centered self-management electronic hub” to promote interaction between the patient and caregiver enables the patient to access necessary health information. This yielded a positive outcome on “self-efficacy and self-management”. The intervention also led to better outcomes in terms of employment and social capital [30].

4. DISCUSSION

The QoL of people with CKD is substantially affected, owing to a deficiency in knowledge regarding the general perception of health, and burden of disease. Moreover, there are dietary restrictions, compromised situations in work field and social relationships that lead to tremendous emotional problems [37, 38]. Patients need to adapt to illness and treatment. Self-efficacy and self-care positively correlate with the QoL in CKD patients [39]. The improvement in QoL is a main element in the manage- ment. It is a challenge to empower and involve the patients in their own treatment [38].

Nurse-led intervention had a positive effect on kidney disease, physical and mental health among adults with type 2 diabetes and end-stage renal disease [40]. A nurse-led educational intervention can play a pivotal role in improving the QoL of CKD patients by enhancing their knowledge and understanding of the disease. Nurse-led intervention has the potential to improve the health status of CKD patients.

4.1. Nurse-led Intervention Increases Self-efficacy

The essence of nursing is the care of the human being. The nursing personnel, from their knowledge and understanding, can effectively apply the strategy of health promotion [38]. Nurses cater their services as ‘being there’ for the patient and their family members during the critical moments of their sufferings. Moreover, nurses have insight into how a chronic disease put its impact on a patient’s life. Hence, nurses can be a suitable coach for imbibing knowledge and training to patients suffering from chronic diseases for their better self-care [41]. Nurses appear to be the most suitable professionals among all tiers of healthcare providers (HCPs) for the successful execution of self-management program for CKD patients. Effective self-management program subsequently influences the QoL of CKD patients [38].

Nurses can contribute to virtual healthcare in the management of chronic diseases, either independently or as a member of a collaborative team [42]. Zaslavsky et al. [43] reported that nurses had higher levels of acceptance of digital technologies compared with physicians and behavioural health consultants. The study also observed that nurses prefer to adopt digital healthcare for rendering their services in the treatment process by promoting healthy behaviors and self-management [43]. One Canadian national survey regarding the nurses’ use of digital health technologies revealed that nurses’ involvement in virtual care has expanded up to nine-fold from 2017 to 2020 [44].

4.1.1. Self-management

Self-management intervention can encourage CKD patients for better management at home on their own. In a study protocol, Ayat Ali et al. [45] tried to evaluate the effect of combined self-management education and psychosocial support for 12 weeks on disease knowledge, self-efficacy, self-management behavior, blood pressure control, adherence to renal diet and QoL.

Enhancing the knowledge and controlling depression can increase self-management as well as self-efficacy in pre-ESRD patients [46]. In a cross-sectional study (n= 91) with pre-dialysis CKD patients, when QoL was measured using the KDQoL-36 questionnaire, it was observed that among the five domains of KDQoL, the mental health component domain had the lowest score [47]. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) can be an effective psycho- logical intervention in decreasing the severity of depressive symptoms in CKD patients [48]. CBT is found to be more effective than non-directive counselling to improve therapeutic adherence and biochemical profiles in CKD patients [49].

4.1.2. Multidisciplinary Team

In 2019, Peng et al. [4] published the observation of their systematic review incorporating 19 RCTs on self-management intervention among CKD patients who were not dependent on dialysis. They found that a multi- disciplinary team involving dieticians, nurses, doctors, and certified physiotherapists providing comprehensive inter- vention in the form of lifestyle modifications, combined with behavior changes, can be effective in improving exercise capacity, lowering blood pressure, C-reactive protein levels, and urine protein [4].

4.1.3. Web-based or Virtual

Virtual care is not a novel concept and rather is an umbrella term that encompasses all of the ways in which HCPs interact with their patients. It includes interaction between patients and/or members in the circle of their care, and this interaction occurs remotely, using any form of information technology, with the aim of facilitating the effectiveness of patient care. Interventions through virtual care can provide fruitful healthcare by offering timely communication, patient education, setting targets for the patients to achieve, and necessary linking of dispersed healthcare teams [50, 51]. Previous studies have reported the beneficial effects of nurse-led virtual care interventions in terms of better control of weight and glucose, improved symptom management, positive self-care behavior, and improved QoL in patients with chronic diseases [52-54].

In telemedicine, different medical conditions are treated without an in-person meeting with the patient. Virtual care is a broader term and includes the application of technologies, such as secured messages, email, and remote monitoring, besides the use of video-conferences and telephone. Telehealth application allows nurses to deliver patient-centric interventions tailored to the patients' needs and facilitate shared decision-making [54]. It also avoids the problem of space constraints and limited treatment time [54]. Telehealth interventions can be cost-effective in providing an evidence-based approach to patient care [51]. Patients receiving telehealth interventions had reduced symptom severity and lesser use of health services compared with those receiving the usual care [53]. Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews have indicated that self-management programs and tools adopted in mobile can facilitate patient management and thereby improve clinical outcomes [55, 56].

The e-learning has recently gained much interest and is being considered as a popular approach to education. Online learning programs are important for non-communi- cable disease prevention and treatment, including CKD [24]. The progression of CKD can be delayed with appropriate access to early treatment, including lifestyle modifications and nutritional interventions [24]. In a 12-month multinational, open-label randomized clinical trial [57] the effects of a web portal, nurse reminders, and team-based care were evaluated regarding their effects on multiple risk factors in patients with diabetic kidney disease. It was found that technology-assisted team-based care for 12 months was beneficial to achieve multiple treatment targets and empowered patients with diabetic kidney disease [57].

The success of healthcare remains indistinguishably linked with the state of the nursing profession. Advanced practice registered nurses not only deliver their services in person but also play a pivotal role in delivering virtual healthcare with their leadership in digital technology-enabled chronic disease management [58].

4.1.4. Diet/Nutrition

In this review of studies, it is found that blood pressure, serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, blood sugar, cholesterol levels improved significantly after the implementation of dietary inter- ventions. Various dietary interventions, such as Medi- terranean diet and plant-based foods, are being evaluated for their role in controlling hypertension and delaying CKD progression. The advantages of a plant-based diet over animal products have been examined. There is growing strong evidence regarding the benefits of a plant-based diet in meeting the daily requirements for delaying the progression of disease. Hence, diet/nutrition therapy under the supervision of a dietician is an important part of medical intervention for CKD [59].

4.2. Virtual or Face-to-face Intervention: Which has Greater Impact?

In the current review, the most common intervention mode was “face-to-face” either alone or combined with other modes. However, electronic or telephone-based intervention was also not infrequent. The debate may arise about which has a greater impact the face-to-face or virtual mode of intervention. In a recent cohort study, Androga et al. [60] found that patients’ satisfaction with their care providers, perceived access to healthcare and overall quality of care were comparable between those receiving care through face-to-face interactions and tele-nephrology [60]. Video-based telemedicine for non-dialysis CKD patients proved to be effective in various aspects, such as the assessment of the clinical condition, utilization of healthcare and monitoring the adherence of patients to clinical advice [61]. Moreover, this approach is patient-centric and can provide an economic advantage in long-term follow-ups. Application of this approach has yielded some improvements in clinical outcomes, mortality, initiation of dialysis, control of blood pressure and biochemical parameters. Moreover, the application of telemedicine has reduced the number of visits to the emergency room, and hospitalization [62]. Last but not the least, lesser waiting time to consult a specialist, fewer cancellations of appointments and reduced travel costs – all have led to a reduction in patient dissatisfaction.

However, the implementation of telehealth programs may face some barriers owing to multiple reasons. Currently, a wide range of devices and applications are available. Besides, there may be perceptions of increased workload, low awareness among staff members, limi- tations in equipment and other resources, multiple stakeholders having competitive targets, variable telehealth needs of patients, legal issues related to sharing protected health information, and uncertainty regarding remote patient-monitoring processes (Supplementary Material- CASP checklist Answering) [51].

4.3. Limitations

The review was not registered in the Prospero. Meta-analysis could not be done owing to heterogeneity of the included studies, such as, variability in study designs, different interventions, wide variations in analytical methods, and outcome measures. As the selected studies were quantitative, qualitative and mixed method studies, it was not possible to generate a forest plot or a similar graphical representation of results to show any point estimate, which is otherwise obtained from studies regarding the same condition or treatment.

4.4. Nursing Implication

Nurses prioritize educating patients on self-management strategies, such as medication adherence, dietary changes, and symptom recognition to enhance active participation in their care. Nurses must encourage patients to monitor health parameters for early detection of complications. Nurses should customize care plans based on patients' needs, literacy, and cultural back- grounds for sustainable interventions. Nurses should provide ongoing support to help the patients to overcome self-care barriers, facilitate behavior change, and manage emotional distress. They also support patients in adopting healthy behaviors by using motivational techniques. Additionally, nurses foster teamwork among HCPs to ensure comprehensive care delivery. They can also utilize advanced technologies to enhance self-management support and improve communication. By implementing these interventions, nurses can help CKD patients to achieve a better (QoL) and improved health outcomes.

Nurses can make a positive impact by care coordination with multidisciplinary teams and thus ensure comprehensive management. Nurses can promote shared decision-making, enhance self-management, increase patient satisfaction and improve patient outcomes. Through effective counseling, nurses can provide emotional support to the patients and connect patients with health care resources. Besides, nurses act as advocates for patients’ individual needs and preferences.

CONCLUSION

Self-management interventions can significantly improve patients’ dietary practices, psychological health, self-management behaviors, health-related quality of life, as well as physiological and biochemical markers in chronic kidney disease patients. Nurse-lead or multidisciplinary team-based interventions are particularly effective in enhancing the quality of life among chronic kidney disease patients. The multidisciplinary approach highlights the importance of an integrated care model that utilizes the expertise of various healthcare professionals to enhance patient outcomes. By equipping themselves with the necessary knowledge, nurses can play a key role in improving the self-care abilities of individuals with chronic kidney disease.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| CKD | = Chronic Kidney Disease |

| QoL | = Quality of Life |

| RRT | = Renal Replacement Therapy |

| CASP | = Critical Appraisal Skills Program |

| MMAT | = Mixed Method Appraisal Tool |

| HRQoL | = Health Related Quality of Life |

| ESRD | = End-Stage Renal Disease |

| PRISMA-ScR | = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses Extension for Scoping Reciews |

| MeSH | = Medical Subject Heading |

| PICO | = Population, Intervention, Comparators and Outcomes eGFR: estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate |

| HDL | = High-Density Lipoprotein |

| LDL | = Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| HCPs | = Healt Care Providers |

| CBT | = Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| RCTs | = Randomized Controlled Trials |

| KDQoL | = Kidney Disease Quality Of Life |