All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Men's Experiences Facing Nurses Stereotyping in Saudi Arabia: A Phenomenological Study

Abstract

Background

Stereotypes about the nursing profession include low ability, low compensation, minimal educational requirements, little autonomy, and a preponderance of women in the field. Contrary to popular opinion, nursing is typically a female-dominated career, and there has been an increase in the number of male registered nurses in the past few years.

Aim

The primary aim of this qualitative investigation is to delve into the experiences and realities faced by male, registered nurses (RNs) in Saudi Arabia and their role in nation-building through Saudi Vision 2030– a national initiative to improve the lives of every citizen based on the pillars: a vibrant society, a thriving economy, and an ambitious nation.

Methods

The study applied qualitative descriptive phenomenology. Twenty-three male RNs were selected through purposive sampling from a total of five hospitals (three government and two private). Semi-structured interviews were used to collect the data. Data was analyzed utilizing Colaizzi's descriptive phenomenological method, and the COREQ checklist was utilized to report qualitative results.

Results

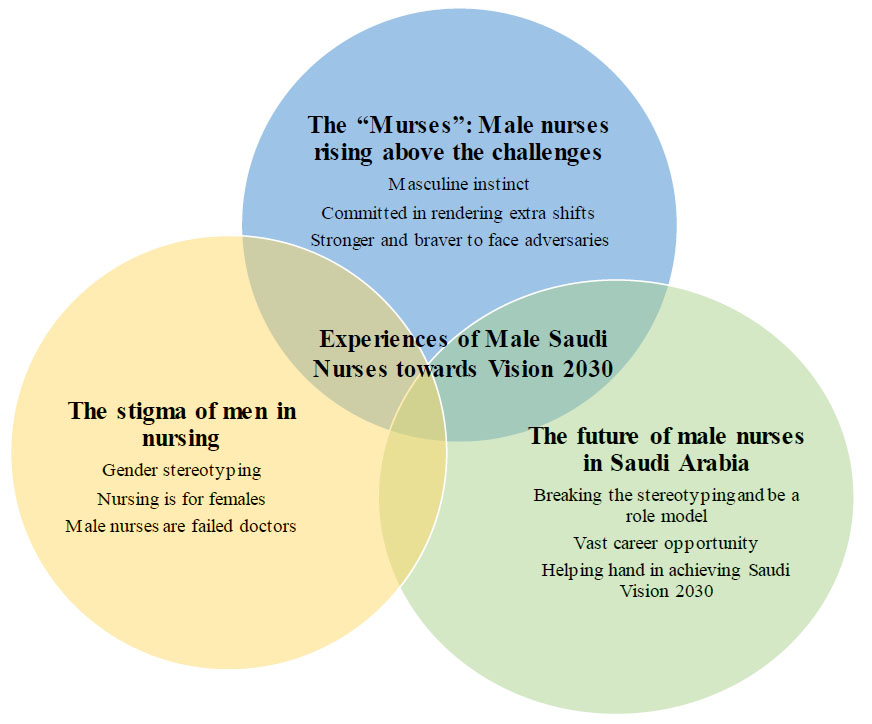

The primary themes were the following: (1) “The stigma of men in nursing” contributes to the idea that men who work in a profession that is primarily dominated by women have a lot of deeply embedded challenges; (2) “The Murses: male nurses rising above the challenges” shows how male RNs deal with specific issues they face while caring for patients in a range of settings, and (3) “The future of male nursing in Saudi Arabia” discusses how male RNs may help the nursing profession grow and develop.

Conclusion

Male RNs experienced both positive and negative professional impressions from people inside and outside the healthcare facilities. In some cases, male RNs faced workplace violence and discrimination. Nonetheless, it was evident that male RNs strove harder to “belong” and to earn respect from the people of Saudi Arabia.

1. INTRODUCTION

Sociocultural variety poses the greatest obstacles to nursing's development in Saudi Arabia as a distinct profession with its own dedicated labor force. Almost half of Saudi Arabia's workforce comprises expatriates or professionals from other countries. Hence, the country is home to people of many different races, ethnicities, and cultural backgrounds. Thus, nurses need to be culturally flexible to effectively serve their patients. The nursing profession is the backbone of healthcare since registered nurses (RNs) constitute the major segment of the hospital staff worldwide [1]. Males and females are both embodied in the profession of nursing. However, females make up most nurses, with the percentage of male nurses reportedly being negligible [2].

Regarding providing care, nurses are indispensable. Despite the industry's long-held stereotype as a “career for women,” more males than ever before are answering the call to become nurses, especially since the kingdom started the Saudi Vision 2030, which requests that all stakeholders in the nursing profession—including administrators, professors, and students work together to transform the profession. Likewise, the ultimate goal of Saudi Vision 2030 is to build an inclusive economy that can support all citizens. Saudi Arabia is laying the groundwork for a bright and prosperous future by fostering an environment that is welcoming to companies of all sizes and by investing in education to train workers for future occupations.

The nursing profession is stereotyped as being dominated by women, low-skilled, underpaid, low educational requirements, and low autonomy [3]. In recent decades, the rising number of male RNs disproves the commonplace belief that nursing is exclusively a female occupation. Some people may assume that male, registered nurses are less expected to show compassion than their female counterparts, however this is not the case. Zamanzadeh et al. [4] have investigated the factors that lead men to become nurses. Men are less likely to consider nursing as a potential profession for some reasons, including inherent gender bias and the public's negative image of the nursing profession. The literature is divided on whether an upturn in the number of male RNs would be beneficial.

Although male RNs have made important contributions to the development of nursing in several subfields, including critical care, mental health, military, and emergency and disaster, the field is still often viewed as a female preserve, especially in Saudi Arabia [5]. Even though males have held nursing positions as far back as the fourth and fifth centuries, nurses and their successes throughout history are primarily a story of women's emancipation. This furthers the stereotype that male nurses do not exist. Subsequently, these associations shed light on how nursing and the job of nurses are viewed and treated differently based on gender in patriarchal societies. Both the nursing skills and masculinity of men are called into doubt [3].

Despite the growing need for nurses, men still make up a tiny fraction of the profession. Concerns about the nursing shortage are joined by worries that the profession does not adequately represent the mixture of the people it serves in relation to gender, nationality, and culture. In fact, men in nursing have been involved in the field for as long as records exist. In the 19th century, the female nursing society disproportionately impacted the chronological ideology of this noble profession, leading many to discount the contributions of men to the field. According to the results, males have played important roles in nursing throughout history, and this should be considered when evaluating the status of male nurses [6].

There is no single study in Saudi Arabia or even in the member countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) exploring this phenomenon. In fact, this study has reexamined the idea that men have it tougher in the nursing profession and offers solutions that will help us better grasp the intersections of gender, nursing, and society in Saudi Arabia. Thus, this qualitative study analyzed the lived experiences of male RNs in a selection of healthcare facilities in the Eastern Region of Saudi Arabia, both public and private. Hence, another study aimed to discover how the nation's male nurses contributed to implementing the Vision 2030 health transformation strategy. By answering the grand tour question, “What are the living experiences of male RNs working in various health institutions, especially aligning the entire nursing workforce towards the Saudi Vision 2030?”

2. METHODS

2.1. Research Design

Descriptive phenomenology was used in this study. Descriptive phenomenology is a philosophical and scientific method that examines how people have encountered a phenomenon in their own lives [7]. As such, it focuses on the finer points of the events rather than the big picture [8]. Therefore, this approach proved suitable for studying how male RNs perceive their professional impressions.

2.2. Setting and Sampling

Twenty-three male RNs from a total of five hospitals (three government and two private) who fulfilled the following criteria were chosen using a purposive sampling technique. The following conditions must be met to participate: All applicants must meet the following criteria: (1) be male RNs working in public or private healthcare facilities in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province; (2) registered with the Saudi Council for Health Specialties (SCFHS); (3) have at least two years of experience as RNs; (4) be eager to offer their perspectives on the topic at hand; and (5) be fluent in English. With this sample strategy in place, participants from all walks of life could explore an abstruse understanding of other people's lived experiences and viewpoints towards the phenomenon under investigation [9]. The interviewees all gave informed consent, and no one was forced to participate. No one had dropped out of the study. As shown in Table 1, the researcher obtained some basic demographic data from the participants.

| No. | Pseudonym | Age | Educational Background |

Nursing Position |

Years in Nursing Profession | Civil Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Argentina | 26 | Undergraduate | Staff nurse | 3 | Single |

| 2 | Brazil | 28 | Undergraduate | Staff nurse | 5 | Single |

| 3 | China | 29 | Undergraduate | Staff nurse | 6 | Single |

| 4 | Denmark | 28 | Undergraduate | Staff nurse | 4 | Single |

| 5 | Egypt | 31 | Undergraduate | Staff nurse | 7 | Married |

| 6 | France | 33 | Master | Head nurse | 9 | Married |

| 7 | Germany | 34 | Master | Nurse Supervisor | 9 | Married |

| 8 | Haiti | 35 | Undergraduate | Staff Nurse | 10 | Single |

| 9 | India | 36 | Undergraduate | Staff nurse | 11 | Married |

| 10 | Jordan | 37 | Master | Nurse Supervisor | 12 | Single |

| 11 | Kenya | 39 | Doctorate | Nurse Supervisor | 14 | Single |

| 12 | Libya | 36 | Master | Head nurse | 10 | Married |

| 13 | Malaysia | 42 | Undergraduate | Staff nurse | 16 | Married |

| 14 | Nepal | 44 | Master | Nurse Educator | 18 | Married |

| 15 | Oman | 43 | Undergraduate | Staff nurse | 15 | Married |

| 16 | Portugal | 45 | Doctorate | Nurse Educator | 19 | Married |

| 17 | Qatar | 46 | Master | Head nurse | 21 | Married |

| 18 | Russia | 48 | Doctorate | Nurse Supervisor | 23 | Married |

| 19 | Singapore | 47 | Master | Head nurse | 21 | Single |

| 20 | Thailand | 50 | Undergraduate | Staff nurse | 24 | Married |

| 21 | Uganda | 53 | Undergraduate | Staff nurse | 25 | Single |

| 22 | Vietnam | 57 | Undergraduate | Staff nurse | 27 | Single |

| 23 | Wales | 55 | Master | Head nurse | 24 | Married |

2.3. Data Collection

The study's primary method was in-depth phenomenological interviews (semi-structured), in which the researchers hoped to comprehensively ascertain the participants' attitudes, beliefs, and desires as male RNs working in various Saudi Arabian healthcare facilities. Data collection was done from December 2022 to February 2023. The interview guide protocol shown in Table 2 was pilot-tested with a sample of three male RNs who did not participate in the study [10, 11]. The researchers' position during the interview should set aside all biases, beliefs, and prior assumptions to avoid misinterpreting the participant's intended experience, meaning, and perception (bracketing) and to develop skills in managing exhaustive phenomenological interviews; the researchers went to seminars and training. The researchers reached the prospective participants through a referral system from various colleagues and peers in the profession. In addition, the researchers scheduled interviews after securing permission and informed consent. Additionally, all participants were elucidated and informed about the study's rationale, procedures, and findings. Participants were interviewed during their free time, before or after their shifts, or at other times that worked best for them. The researchers and participants decided on a time and place for individual interviews, which lasted between 30 and 45 minutes (such as cafes, restaurants, recreational facilities, and residential homes). No more than three interview sessions were conducted in total, differing on the worth of the initial conversation and the researchers' need for clarification. Definitively, the interviews were recorded so the researchers could refer to them afterward. The researchers made notes in a notebook during the interview, transcribed the conversation, and took analytical field notes.

| • Can you please tell me something about yourself? • How would you describe yourself as a male nurse in Saudi Arabia? • Can you please tell me about your idea(s) about men in nursing? • Can you please tell me some instances where you experienced hardships as a male nurse? • How would you describe your workplace? • How do you handle unfavorable situations? • How does your workplace support men in nursing? |

• Where are there any issues of diversity and inclusivity among men in nursing? • If so, what interventions were implemented to eliminate potential challenges faced by men in nursing? • How do you support men in nursing? • How does this experience change your personal and professional life and endeavors? • What are your plans in the coming years? • What are your final thoughts pertaining to men in nursing? • How do you see men in nursing in the coming years? |

2.4. Data Analysis

Colaizzi's [12] unique seven-step procedure offers a rigorous analysis because each stage remains as close as possible to the data. The result is a participant-validated, succinct yet comprehensive explanation of the phenomenon under study. The following steps were conducted: (1) Familiarization - reading all participants' narratives over multiple periods to get to know the data; (2) Identifying significant statements - all remarks in the reports that are directly relevant to the phenomenon under examination are identified by the researcher; (3) Formulating meanings - by analyzing the meanings of the statements with high significance and relationship towards the phenomenon, this can lead to a better understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. In order to maintain a tight relationship to the phenomenon as stated in the participants' accounts of their lived experiences, the researcher must automatically “bracket” his or her presuppositions; (4) Clustering – formulated meanings from the significant statement must be clustered into major themes present across the various narratives. Moreover, it is essential to bracket off any assumptions, especially to keep any preexisting theory from influencing the conclusions; (5) Exhaustive description - the next step is to come up with a thorough description of the phenomenon, expanding on each of the parts that arose in step four; (6) Describing the fundamental structure of the phenomenon - the researchers provide a brief explanation encompassing the most crucial elements of the phenomenon's framework; and (7) Verification – the researchers return the findings to all participants and ask them to evaluate how well it describes their lived experience. Based on the results of this new information, he or she may decide to revise the prior stages of the analysis [13].

2.5. Scientific Rigor

The following criteria were considered to ensure the study's scientific rigor: confirmability, credibility, dependability, and transferability. All interviews were recorded and transcribed on the same day to ensure accuracy and consistency. The researchers became aware of the biases by keeping a reflective journal. So that the findings would be applicable in a variety of contexts, the researchers enlisted the help of three male nurses from various regions of the country. To ensure data validity, relevance, and usability, the researchers consulted three external experts with vast experience publishing qualitative studies in the nursing profession. Moreover, the researchers made audio recordings, typed up transcripts of the interviews, and took detailed notes in the field to ensure that the same results would be obtained if the data were independently verified. Anyone may verify the accuracy of the reported data by reviewing the transcript and the precise terminology employed to define the phenomena [14-16]. COREQ's standards were utilized and followed in reporting the results of this qualitative research [16].

2.6. Ethical Considerations

A certificate from the Institutional Review Board of Imam Abdulrahman bin Faisal University (IAU-2022- 04-543) was acquired. Before gathering data, all male nurses who agreed to participate signed the informed consent, which complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and allows researchers to disclose their statements without revealing their identities.

| Keywords/Phrases | Theme Clusters | Major Themes | Meaning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender gap Gender disparity Indifferences He-man Gay Third sex Pseudo-doctors Not for men Female work Conflict makers Misconceptions Intimate touch Homosexuals Mischief-makers |

Only for females Failed doctors Stereotyping Indifferent Stigma Female dominating Trouble-makers Misbehaving Rude behavior Misinterpretations Sexual harassment Macho man Malicious Subclass |

Gender stereotyping | The stigma of Men in Nursing | This theme downplays the idea that men in the predominantly female nursing profession have a wide range of deep issues. |

| Nursing is for females | ||||

| Male nurses are failed doctors | ||||

| Stronger Overtime Masculinity Extra shifts Braver Adversaries Rising up Withstanding problems Realization COVID-19 Pandemic Better person |

Instincts Hardworking Workplace violence Challenges Navigation Commitment Bullying Reflection Perseverance Determination Zeal Professionalism Strong |

Masculine instinct | The “Murses”: Male nurse rising above the challenges | This theme highlights the ways in which male nurses successfully navigate the unique hurdles they face while providing care to patients in a variety of settings. |

| Committed in rendering extra shifts | ||||

| Stronger and braver to face adversaries | ||||

| Leadership Sense of purpose Role model Career break Management Social learning Love for nursing Futuristic Education Practice Research Change agent Spear headers |

Breaking norms Saudi Vision Helping hand Career opportunities Vision 2030 Creativity Innovativeness Contemporary New ideas Contribution Administration Brotherhood |

Breaking the stereotyping and be a role model | The future of male nurses in Saudi Arabia | This illustrates how male nurses may aid in the development of the nursing profession in a way that is in line with the Saudi Vision 2030's health reform agenda. |

| Vast career opportunity | ||||

| Helping hand in achieving Saudi Vision 2030 | ||||

3. RESULTS

Three main themes were extracted from nine theme clusters that emerged from the participants' accounts of their daily lives as male RNs in Saudi Arabia. Three major themes emerged: “The stigma of men in nursing”, “The nurses: male nurses rising above the challenges”, and “The future of male nurses in Saudi Arabia”. Table 3 shows the summarized keywords, theme clusters, major themes, and operational meanings.

3.1. Theme 1: The Stigma of Men in Nursing

The first theme, “the stigma of men in nursing,” downplays the idea that men in the predominantly female nursing profession have a wide range of deep issues. Three theme clusters emerged from this major theme: “gender stereotyping”, “nursing is for females”, and “male nurses are failed doctors”.

3.1.1. Gender Stereotyping

Gender stereotyping shows how men are treated differently based on their gender in the nursing profession due to their preferences and actions.

“The public does not hold high expectations for male nurses. The worst part is that they considered male nurses to be of the “third sex.” It's unfortunately that they had such a negative outlook about the male nurses...” (P14)

“Macho conduct” is a common reason why men are stereotyped as disruptive in nursing. Although they had never met any male nurses, they assumed that all of them were rude and condescending because of the stereotypes…” (P9)

3.1.2. Nursing is for Females

Nursing is for females refers to the belief that nurses are exclusively women and that men have no place in the field.

“My patient's family insisted on having a female nurse assigned to them from the very beginning. She specifically requested that the patient be cared for by a female nurse. She brought it up in a direct conversation with the chief nurse…” (P9)

3.1.3. Male Nurses are Failed Doctors

Male nurses are failed doctors, promoting the misconception that men working in nursing are secretly upset because they were not accepted to medical school.

“During one of my shifts, I eavesdropped on a conversation between two doctors. When they said the nurses were just failed doctors, I didn't think they were being serious. Some male nurses, according to this theory, are disgruntled MDs who tried to go to medical school but were rejected…” (P13)

3.2. Theme 2: The “Murses”: Male Nurses Rising above the Challenges

The second major theme, “Murses: Male nurses rise above the challenges,” highlights how male RNs successfully navigate the unique hurdles they face while providing care to patients in various settings. The term “nurses” came from the participants to identify them being in a female predominant profession, which they believed to be a unique identification for a male nurse. Three theme clusters emerged: “masculine instinct”, “committed to rendering extra shifts”, and “stronger and braver to face adversaries”.

3.2.1. Masculine Instinct

Masculine instinct demonstrates the benefits of self-reflection and the development of mature intuition for male nurses.

“From prejudice to physical threats, I've experienced everything at work. But if there's one thing I've learned from being a man, it's how to be a better person and worker. I now see how our efforts are contributing to the realization of the national Vision 2030…” (P1)

3.2.2. Committed to Rendering Extra Shifts

Committed to rendering extra shifts indicates that male nurses, especially in times of crisis, are willing to go above and beyond by working more hours.

“One benefit of being a man in nursing is that we tend to be more tenacious and willing to work longer hours and more shifts. If there is an emergency or a natural disaster, man nurses almost invariably step up to help. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, it was clear that male nurses were always on the go...” (P17)

3.2.3. Stronger and Braver to Face Adversaries

Stronger and braver to face adversaries shows the dedication of male nurses and how they keep going even when things do not go their way.

“Despite the difficulties I've encountered, I've maintained the conviction that there's something to be gained from every situation. Knowing that so many people's lives depend on my abilities as a guy in this industry necessitates tremendous boldness, bravery, and persistence on my part. Being a nurse is a privilege, and I remind myself of that often...” (P2)

3.3. Theme 3: The Future of Male Nurses in Saudi Arabia

The third and final major theme is “the future of male nurses in Saudi Arabia”, which shows how male RNs may provide for the growth and development of the nursing occupation in a way consistent with the health reform objective of Saudi Vision 2030. Three theme clusters emerged: “breaking the stereotyping and being a role model”, “vast career opportunity”, and “helping hand in achieving Saudi Vision 2030”.

3.3.1. Breaking the Stereotyping and being a Role Model

Breaking the stereotyping and being a role model means that male nurses are advocating for a more inclusive nursing environment in which stereotypes about males working in the field are challenged. Thus, it also reflects how male RNs can serve as role models to male nursing students.

“Working in healthcare, especially as a nurse, is a very honorable profession. You can be a nurse if you have the head, heart, and hands for the profession, regardless of your gender. Getting rid of the negative connotations surrounding the profession is essential to ensuring its continued success. I believe that we must be role models to male nursing students. If they see us being successful in this field, then I am sure they would follow our lead...” (P23)

3.3.2. Vast Career Opportunity

Vast career opportunity how male RNs are offered unprecedented possibilities for advancement and a broader range of experiences in their chosen field.

“To be frank, nursing is mostly a female-dominated field. Men, surprisingly, have access to a wide variety of nursing-related professional paths, including direct patient care, education, management, and research. Being a nurse is the most rewarding profession, in my opinion...” (P7)

3.3.3. Helping Hand in Achieving Saudi Vision 2030

Helping hand in achieving Saudi Vision 2030 proves that male RNs are fundamental contributors to the solution to the nation's problems and the key to the success of the government's future goals.

“Recruiting and retaining men as nurses is a critical part of Saudi Vision 2030's plan to modernize the country's healthcare system. Our nation's future is bright, and it will only get brighter as we embrace diversity and welcome all people. Never lose sight of the fact that nursing is both the science and the art of caring for people of all shapes, sizes, sexes, and socioeconomic backgrounds…” (P18)

4. DISCUSSION

There is evidence that the first school dedicated to nursing was established in India sometime around 250 B.C. It used to be that only men were allowed to work as nurses since only men were considered “pure” enough. In fact, the contributions of men to the nursing profession are often overlooked. Male caregivers were common in early communities, the military, and the religious sphere [17]. Yet men serving under monastic orders or in the military cared for the impoverished, sick, or injured a millennium ago. Historically, this position was held by males who cared for the sick and elderly [18]. How did women come to dominate the field if this historical fact holds true? Conflicts between 1850 and 1950 reshaped the roles of men and women; males went to fight, while females took on the traditionally female function of nurse. “Every woman is a nurse,” Florence Nightingale said in her 1859 book “Notes on Nursing,” solidifying the gendered division of labor that persists to this day. Despite being underrepresented in the nursing profession, males continue to show this kind of dedication to helping those in need [19].

Before Nightingale, there were already men working as nurses. Nursing males have gone from heroes to outcasts and medical school dropouts [20]. While studies show that men and women are equally drawn to nursing, males typically enter the field through nontraditional routes. Feminists worry that the prevalence of male leaders in the nursing field will harm the standard of care patients receive. Both sexes of patients have strong opinions about which nurse would have been most suited to care for them. As respect for the pioneering work of men's nursing ancestors develops, it is important to do everything possible to ensure that men continue to play an integral role in the field [21, 22]. Three major themes emerged from this qualitative study's findings as seen in Fig. (1): (1) “The stigma of men in nursing”; (2) “Murses: Male nurses rising above the challenges” and (3) “The future of male nurses in Saudi Arabia” were written from the perspective of male RNs in Saudi Arabia and their experiences.

The first major theme, the stigma of men in nursing, is depicted by the participants as “gender stereotyping”, “nursing is for females”, and “male nurses are failed doctors”. Grinberg and Sela [23] stated that nursing has traditionally been female-dominated, with few male nurses. Thus, it impacted the general view of nursing as a profession. It is no secret that male RNs experience sexism and discrimination on the job. Male RNs still endure discrimination, regardless of their qualifications or experience. Budu et al. [24] stated that even though most male RNs enter the field to pursue personal fulfillment, they face additional discrimination on the job due to sociocultural stereotypes of male RNs as “third sex,” “Macho Men” and “Mischief-makers” and because they are excluded from participating in delicate procedures at the hospital. This is a problem since male RNs are less likely to encounter other male nurses than female nurses. Male RN discrimination often leads to workplace violence or horizontal bullying [13, 15].

Suspicion of intimate touch is another cause for male RNs and nursing students to worry about the stigma they face in the field [25]. Based on interviews with male nurses, Harding [26] identified four specific concerns regarding touch: (1) sexism in the use of touch; (2) men's touches are subjected to high sexualization; (3) how easily men can be falsely accused of sexual misconduct; and (4) a lack of instruction in nursing schools on how to help male students feel safe during physical contact and avoid making false allegations of sexual assault. Males are put under unnecessary stress because of this, which can lead to role strain and conflict. In contrast to their female counterparts, nursing men are stereotyped as less empathetic. No single man's abilities should be seen as indicative of all men, and no single woman's abilities should be taken as indicative of all women. Every participant in this qualitative investigation stated that they genuinely care about helping others. The stereotype of male RNs as intolerant, gruff, and irritated is inaccurate. The absence of a “role model” in nursing has contributed to this stress. Male RNs must often serve as pioneering role models from the get-go. This finding challenges the hypothesis that religious belief discourages male nurses from entering the field. Promoting tolerance for gender diversity in nursing requires informing the public about the contributions that men's healthcare services can provide [24]. In addition, research shows that men have a greater affinity for technical details, whereas women are more interested in building a rapport with their patients while protecting their rights to privacy and secrecy [27].

During the interviews with male RNs, they characterized their lived experiences as to “masculine instinct”, “committed to rendering extra shifts”, and “stronger and braver to face adversaries”, which leads to the second major theme called “Murses: Male nurses rising above the challenges”. It could be assumed that men do well in the nursing profession. Due to their greater capacity for leadership and lower numbers, they may have greater financial success and faster job advancement. Despite this, many studies of men in nursing have found that they feel unfulfilled in what is generally viewed as a female-dominated profession and that their masculine identities are at odds with their roles as nurses [28].

Patients of all types had a generally deleterious image of male RNs but a more encouraging view of a male RN who cared for them. In a study conducted in Jamaica, the gender ratio of nursing staff can be altered with the help of exemptional characteristics of male RNs, commitment to patient advocacy, cautious caregivers, empathy, increased agility and stamina, and sense of humor [29]. Despite efforts to recruit more men into nursing, the percentage of male RNs remains low. Particularly in the context of today's shifting sociocultural and healthcare landscapes, resolving this imbalance is crucial if the healthcare staff is to mirror the variety of people. Men may see this profession as rewarding, but the strong cultural association between the profession and femininity may discourage them. The majority of the participants highlighted that to survive the workplace challenges, a male RN should demonstrate intentionality in healing, the value of contemplative spiritual practices, and the importance of growing self-awareness [21, 22].

Finally, the third and final theme, “the future of male nurses in Saudi Arabia”, this theme generated three theme clusters such as “breaking the stereotyping and being a role model”, “vast career opportunity”, and “helping hand in achieving Saudi Vision 2030”. The majority of male registered nurses have a strong dedication to their profession, but they will not fully immerse themselves in the field until certain obstacles are removed. Research into how to attract more males into the nursing workforce is sure to be conducted soon, and nurse managers may play a pivotal role in this [2].

Male nursing students and new graduates may not find many male role models in the field. Mentors serve as role models by demonstrating appropriate clinical and professional conduct. Male and female nurses have equal potential as clinical mentors, although a male RN in a traditionally women-dominated workplace may feel uncomfortable confiding in a female coworker about certain concerns. It is possible that a more seasoned male RN will have encountered subtle forms of discrimination that a female nurse might miss.

Promoting nursing as a field that welcomes applicants of both sexes requires community service projects. Students in Saudi Arabia are encouraged to look up to male RNs during the clinical rotation, orientation, internships, field training, and on social media. So, people in Saudi Arabia do not realize how important male RNs are, and that's why the internet is so important in breaking down stereotypes5. The status of nurses in Saudi Arabia needs to be improved so that more people choose to become nurses as their profession of choice. Additionally, the media must do its part to change the public’s negative view of nursing.” [30].

4.1. Implications

To get rid of these stereotypes and biases, nursing needs to be shown as an important and serious job that both men and women do. Specifically, this effort is being done through collective action from nursing organizations, healthcare facilities, universities, and the media, as well as through participation in health policy. It is suggested that the nursing profession can undergo a creative and healthy workplace environment and gender-neutral rebranding at the national level, that education can start early (in preschools and elementary schools), that prominent men in the nursing profession serve as role models at the national and local levels, and that unconscious bias training.

If more men in nursing work in leadership roles, it will help shift the public's view of nurses overall and give them a voice in policymaking. The demands and needs of male registered nurses in the kingdom necessitate the establishment of support coming from organizations like the American Association of Men in Nursing (AAMN), which encourages men to become nurses and grow professionally by providing them with encouraging articles, scholarships, and special events.

4.2. Limitations

This qualitative research was interested primarily in male RNs' first-hand accounts of their lived experiences and did not collect the views of female RNs on this topic. Male registered nurses from five hospitals in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province were interviewed for this study. The findings of this qualitative inquiry might not be applicable throughout the entire kingdom.

CONCLUSION

Current research on men in nursing shows that traditional notions of masculinity have been a major obstacle for men interested in entering the field. Gender norms can be bent under extreme situations like war and severe nurse staffing shortages. Historically, male nurses have been clustered in the field of mental health care; more recently, they have been overrepresented in positions of leadership and specialization that are more compatible with stereotypes of masculinity. When men's contributions to nursing are ignored, male nurses are left in the dark regarding their profession's roots and evolution. It also helps keep gender dynamics, which have affected nurses' experiences across the board, under the radar. To the detriment of nurses and the nursing profession, such relations continue to be misunderstood and, hence, unchecked.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| AAMN | = American Association of Men in Nursing |

| MD | = Medical Doctors |

| RN | = Registered Nurses |

| SCFHS | = Saudi Council for Health Specialties |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

An institutional review board certificate was given by Imam Abdulrahman Bin Faisal University (IAU-2022-04-543).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures involving human participation were in accordance with the bioethical standards of the institutions and research committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). No animals were involved in this study.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All participants agreed to publish their narrative accounts without specification of their personal information. Privacy and confidentially were highly imposed throughout the study processes. Moreover, they have all signed an informed consent form and are allowed to withdraw from the study at any time.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, [JTS]. The data are not publicly available due to information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express the deepest gratitude to the male registered nurses as the study’s participants for their contributions, hard work, and dedication to sharing their lived experiences, which can shed light for other male registered nurses and students to continue striving harder to achieve the Saudi Vision 2030.