All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Conceptualisation and Definition of Personal Recovery among People with Schizophrenia: Additionally Review

Abstract

Background:

Personal recovery is an essential mental health goal in schizophrenia. Personal recovery is deeply individual and cannot be uniformly characterised for each person. Therefore, the concept and definition of personal recovery in schizophrenia are still ambiguous.

Objective:

To clarify the definition and conceptualisation of personal recovery in schizophrenia patients

Methods:

The study followed Arksey and O’Malley’s framework stages. Related electronic documents were searched in ScienceDirect, Scopus, SpringerLink, and Google Scholar.

Results:

Ten systematic review studies were included in this paper. Recovery conceptualisation is various perspectives of people with schizophrenia regarding personal recovery as follows: “Recovery as a journey”, “Recovery as a process”, “Recovery as an outcome”, and “Recovery components.”. In addition, it was codified into an operational definition congruent with the CHIME plus D (connectedness, hope, identity, meaning in life, empowerment, and difficulty).

Conclusion:

Conceptualisation of personal recovery appears in line with the personal recovery process and outcomes close to each other. Therefore, instruments should be developed for measuring both recovery processes and outcomes simultaneously. Additionally, nursing intervention should be designed by aiming to promote and address CHIME plus D. Personal recovery studies in schizophrenia patients have been limited to developed countries. Therefore, in order to acquire a more thorough conceptualisation and characterisation, future research ought to take into account the characteristics, determinants, and outcomes of personal recovery among people with schizophrenia who come from developing nations and minority ethnic groups.

1. INTRODUCTION

Once people are diagnosed with schizophrenia, they undergo radical shifts in their views, behaviors, feelings, and personalities [1]. Usually, people want to know when they may expect them to feel better. To “recover” is to return to one's previous condition is the common understanding of the term [2]. This situation among people with schizophrenia is uncertain and unpredictable [3]. Additionally, schizophrenia is considered chronic and devastating. Patients are disturbed by the appearance of residual symptoms after going back to the community [4]. However, recovery from schizophrenia is possible [5]. The recovery model has been focused on several studies and defined as the optimal mental health objective in the field of schizophrenia since the 1980s [6]. There are complex and multifaceted notions of different ways to describe recovery. Three different forms of recovery are most mentioned: clinical, functional, and personal recovery [7].

Former existing knowledge about recovery was predominant in the biomedical model from the perspective of mental health providers, which defines and emphasises two forms of recovery: clinical and functional recovery [8, 9]. Clinical recovery is defined as remission for a six-month to two years period from a mental illness that does not hinder function and independent living without supervision by informal carers [10, 11]. Functional recovery is linked with clinical recovery in the function of assisting patients in achieving a reduction in mental illness symptoms by focusing on the capacity to live independently for at least two years without a relapse, engage in social connections, and sustain relationships with professional and full or part-time work or education performance [11, 12]. Both forms of recovery have been applied for schizophrenia clinical and functional evaluation through mental health professional views.

Conceptually, the perception that psychotic episodes associated with schizophrenia are not only one of the symptoms and impairments but also one of the most significant obstacles to a sense of self. In other words, the restoration of one's sense of self is an important part of the recovery process from mental illness [13]. For example, a person with schizophrenia may appear to suffer from a severe mental illness, but they may have a far stronger sense of self. Inversely, symptoms and disability may worsen while self-awareness is still modest. These address the subjective recovery aspect. Meanwhile, in the professional setting, which encountered the mental health consumer movement, that advocated for the subjective aspect of healing to be given equal weight to the objective recovery aspect [14]. As a result, the mental health professionals’ team, including mental health nurses increased significantly their concern and consideration about how to design the service to encourage positive emotion with a healthy sense of self of a person with mental illness [15].

Later on, scientific evidence regarding recovery is the most addressed in terms of the subjective or personal recovery model [16, 17] until the present. Personal recovery places emphasis on areas of personal development with crucial components of the subjective healing process from mental illness, such as regaining health, self-empowerment, having a sense of hope and direction in life, redefining oneself, overcoming stigma, cultivating supportive relationships, accepting responsibility, making sense of one's life, and leading a satisfying life [9, 18-20]. Additionally, personal recovery is not only something that involves a person, but also involves family, friends, coworkers, peers (who have been through the same thing), mental health professionals, and the many services offered by the public mental health system due to those factors are correlated with personal recovery [19, 21].

Despite the fact that three overlapping, but nonetheless different understandings of recovery have been proposed, mental health professionals have gravitated towards clinical and functional recovery, whereas patients typically find more value in personal recovery. However, the three forms of recovery have not been seen competing with one another, but rather as parts of the recovery process and outcomes that go together, by clinical recovery mediated functional recovery and personal recovery [7, 11, 22]. Notably, mental health nurses should be focused on the promotion of personal recovery due to personal recovery places more value on the individual's knowledge and encompass a holistic nursing paradigm more than just clinical and functional recovery [11]. Additionally, this concept would lead to comprehending the endpoint of nursing care more than the clinical outcome, which is suited to the global mental health policy that focuses on personal recovery [21, 23, 24].

However, personal recovery has emerged from opinions in mental illness customers. Consequently, this concept is wide-ranging, profound, and cannot be uniformly characterised. There is no one approach that works for or fits enough for every patient. A person's recovery from schizophrenia can take many different forms. Therefore, it is essential to clarify personal recovery conceptualisation among people with schizophrenia in order to assist mental health nurses to understand and learn about the diversity of viewpoints on the personal recovery concept, in order to clearly identify the goals of caring for people with schizophrenia which will lead to conduct the proper nursing practice or nursing intervention to promote personal recovery in future.

2. METHODS

This study was set up to review personal recovery among persons with schizophrenia. It was a scoping review designed specifically to handle key concepts in the overall study in a specific area [25]. Arksey and O’Malley framework stages were employed [25, 26], which include (1) formulating a research topic; (2) finding relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) data mapping; (5) article collection and analyses, and (6) consultation.

To achieve the research goal, specific inclusion criteria for primary research studies on a conceptualisation of personal recovery among people with schizophrenia were established, in order to ensure the data's relevance. Those were focused on personal recovery among persons with schizophrenia, using systematic review and/or meta-analysis, and English language. Exclusion criteria were non-peer-reviewed articles, other than English, and focused on personal recovery among other mental illnesses in general.

2.1. Search Strategy

The range of years covered by this review was from 2010 all the way up to 2022. In order to find what data was needed, a systematic search technique was used that included not only the original keywords, but also their variations and synonyms. The author defined mental health care as consisting of the terms “systematic review”, “recovery”, “schizophrenia”, and “serious mental illness”. To achieve maximum precision, an iterative process for the search terms was done by adding and eliminating words. Searching was systematically performed in the following databases: ScienceDirect, Scopus, SpringerLink, and Google Scholar.

2.2. Quality Appraisal

All relevant articles were independently appraised using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR). This 11- item evaluation tool assesses methodological quality, presentation, and the risk of bias in systematic reviews. The articles which did not include a comprehensive search strategy, and items with less than five out of eleven points were excluded [27].

2.3. Study Selection

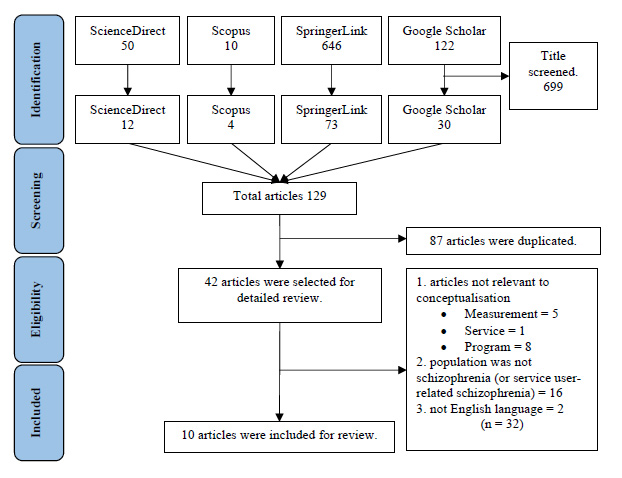

After finishing a comprehensive literature search, all titles were screened. Out of 828 articles, 699 were identified as irrelevant to the study. Then, 87 of 129 articles were duplicated, and 42 articles remained. These 42 articles were read and checked based on the inclusion criteria. Out of 32 articles that were evaluated and subsequently excluded 14 were irrelevant with a conceptualisation of recovery, 16 were different populations, and 2 were not in English. Finally, the analysis included 10 articles. Those were extracted based on their aim, number of studies and time frame, and findings. These were selected based on the PRISMA model using the flowchart shown below in Fig. (1) [28].

| Author/Year | Purpose | Number of Studies and Time Frame | Population who Provides Personal Recovery Viewpoint in Selected Studies | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade 19 | To synthesise published descriptions and models of personal recovery into an empirically based conceptual framework. | A total of 97 papers contained qualitative studies, quantitative studies, narrative literature reviews, book chapters, etcetera. (From January to August 2011) |

91 studies reported individual recovery viewpoint among persons living with mental illness. 6 studies reported mental health illness patients with people of colour and minority ethnic. | Characteristics of the recovery journey 1. An active process 2. Individual and unique processes 3. Nonlinear procedure 4. A journey 5. Stages or phases 6. Struggle 7. Multidimensional process 8. A gradual process 9. A life-changing experience 10. Without a cure 11. Aided by supportive care and healing environment 12. Can occur without professional intervention 13. Trial and error process Recovery processes: 1. Connectedness 2. Hope and optimism 3. Identity 4. Meaning in life 5. Empowerment Recovery stages mapped onto the transtheoretical model of change. 1. Precontemplation 2. Contemplation 3. Preparation 4. Action 5. Maintenance and growth |

| Slade, Leamy, Bacon, Janosik, Le Boutillier, Williams and Bird 29 | To validate a CHIME conceptual framework and then characterise by country the distribution, and scientific foundations | A total of 115 papers (qualitative research, nonsystematic literature reviews, and position papers) (From September 2009 to August 2011) | Mental health illness patients | The main finding is underpinned by CHIME framework based on Western European and North American models, so a broader scientific evidence base is needed. Two-way exchange for spreading the concept is research from culturally more dissimilar countries that would aid in clarifying both embedded social and political assumptions about the nature of recovery and the individualistic rather than collectivist focus of current recovery models. |

| Jose, Lalitha, Gandhi and Desai 30 | To identify the consumer perspectives of recovery from schizophrenia | 19 Qualitative 5 Quantitative 1 Mixed (In the years 2000 to 2013) |

23 papers studied using patient viewpoint of - Recovered patients with SMI - SMI - Persons living with schizophrenia - chronic schizophrenia patients 2 papers studied by using medical students and nurse perspective. |

Recovery themes in five areas Recovery as a process 1. Process orientation Recovery as outcomes 2. Self-orientation 3. Family orientation 4. Social orientation 5. Illness orientation |

| Clarke, Lumbard, Sambrook and Kerr 31 | 1. To provide a narrative synthesis of forensic mental health patients’ perceptions of recovery. 2. To explore the meaning that service users make of recovery |

11 Qualitative (From their inception to August 2014) |

Forensic mental health patients | Recovery components 1. Connectedness 2. Sense of self 3. Coming to terms with the past 4. Freedom 5. Hope 6. Health and intervention |

| Stuart, Tansey and Quayle 32 | To carry out a review and synthesis of qualitative research to answer the question, “What do we know about how service users with severe and enduring mental illness experience the process of recovery?” | 12 Qualitative (From their inception to August 2014) |

Severe and enduring mental illness (SEMI) Mental health service user who had experiences of recovery | Recovery processes: CHIME plus four 1. Connectedness 2. Hope and optimism 3. Identity 4. Meaning in life 5. Empowerment 6. Difficulties 7. Therapeutic input 8. Acceptance and mindful awareness 9. Returning to, or desiring, normality |

| Morera, Pratt and Bucci 36 | To examine staff views about psychosocial aspects of recovery in psychosis |

A total of 15 papers were included. 8 qualitative 7 quantitative (From their inception to August 2014) |

Mental health professionals who service clients with schizophrenia | There was evidence reported that mental health professionals endorsed psychosocial views of recovery, but most studies recommended they endorsed clinical and functional recovery, so, they emphasised the importance of pharmacological rather than psychosocial interventions. |

| Wood and Alsawy 33 | To conduct a systematic review of qualitative literature examining service users’ experiences of recovery from psychosis using thematic synthesis. |

17 qualitative studies (June 1946 – June 2015) |

Psychosis service user | Recovery as journey 1. Prior to psychosis, pre-psychosis stress and trauma 2. An episode of psychosis, loss, uncertainty, and fear 3. Integration of psychosis synthesis and acceptance 4. Rebuilding oneself and life 5. Encompassing psychosocial factors |

| Van Eck, Burger, Vellinga, Schirmbeck and de Haan 9 | Perform meta-analysis investigating the relationship between personal and clinical recovery. |

37 quantitative studies (in a meta-analysis) (From January to February 2017) |

Patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders | In this case, the correlation between clinical and personal recovery appears to be weak to moderate. As a result, when treating and following up with people who have schizophrenia spectrum disorders, it is important to take their clinical and emotional progress into account. |

| Ellison, Belanger, Niles, Evans and Bauer 34 | To assess the concordance of the recovery literature with the recovery definition by SAMHSA | 67 review articles and policy papers (From 1985 until 2014) | - Serious mental illness - Mental health disorder - Schizophrenia affective disorder |

SAMHSA Recovery Components 1. Individualised and person centred 2. Empowerment 3. Hope 4. Self-direction 5. Non-linear/many pathways 6. Strengths-based 7. Respect 8. Responsibility 9. Peer-support 10. Holistic 11. Addresses trauma 12. Relational 13. Culture Four SAMHSA dimensions of recovery 14. Health 15. Home 16. Purpose 17. Community |

| Temesgen, Chien and Bressington 35 | 1. To examine the concept of subjective recovery from recent-onset psychosis. 2. To identify common factors associated with this recovery process. |

The review included ten studies. 8 Qualitative 1 Quantitative 1 hybrid method (From their inception to April 12, 2017) |

- First episode psychosis - Recent onset psychosis | Recovery outcome 1. Bounce back 2. Be in self-control. 3. Have a vision. Recovery process 1. Multidimensional and personalised 2. Slow and gradual 3. Transition from experiences of self-estrangement to self-consolidation 4. Change in self 5. Not all participants went through all stages. 6. Non-linear social 7. Beyond symptom control and medication compliance 8. Have positive features that the experience of illness has brought on Endeavors during recovery journey 1. Reconciling with the illness experience 2. Understand recovery 3. Maintain an optimistic view of recovery 4. Value of self 5. Control over chaos 6. Treatment negotiation and acceptance 7. Negotiating for success 8. Social participation 9. Engaging in services and support 10. Self-help; help from others 11. Fight stigma 12. Suppress or defeat disabling factors. |

3. RESULTS

Table 1 presented the description of the ten included articles. The ten articles were published between 2011 and 2019. Eight out of ten articles addressed the conceptualisation of personal recovery by analysing and synthesising it through mental health patients’ perspective [9, 29-35]. One review was delivered through mental health provider's viewpoint [36]. The remaining review synthesised personal recovery framework through both mental health service user and mental health professional perspectives [19]. Most reviews figured out personal recovery conceptualisation in a Western context, and only a study by Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade [19] combined six articles that focused on individual viewpoint recovery through mental health illness patients with people of colour and minority ethnic to analyse recovery conceptual framework.

Ten systematic reviews were analysed, extracted and classified into four categories: “Recovery as a journey,” “Recovery as a process,” “Recovery as an end,” and “Recovery components.” Details are provided below.

3.1. Recovery as a Stage of a Journey

Three reviews noted recovery as a journey. They showed a particular characteristic in each article. Firstly, the study by Leamy and colleagues in 2011. The personal recovery journey consisted of thirteen characteristics: 1) an active process, 2) individual and unique processes, 3) nonlinear procedure, 4) a journey, 5) stages or phases, 6) struggle, 7) multidimensional process, 8) a gradual process, 9) a life-changing experience, 10) without a cure, 11) aided by supportive and healing environment, 12) can occur without professional intervention, and 13) trial and error process. Secondly, the recovery journey of recovery would shift throughout. Four specific stages of the recovery journey were identified: 1) Person prior to psychosis, 2) episode of psychosis, 3) integration of psychosis and 4) rebuilding oneself and life 33. Lastly, Temesgen, Chien and Bressington 35 illustrated the endeavor for recovery appears from the journey of personal recovery, including 1) reconciling with the illness experience, 2) understanding recovery, 3) maintaining an optimistic view of recovery, 4) value of self, 5) control over chaos, 6) treatment negotiation and acceptance, 7) negotiating for success, 8) social participation, 9) engaging in services and support, 10) self-help; help from others, 11) fight stigma, and 12) suppress or defeat disabling factors.

3.2. Recovery as a Process

Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade 19 is the first review presenting the CHIME personal recovery process framework, including 5 elements (connectedness; hope and optimism about the future; identity; meaning in life; and empowerment). Later on, three reviews reported personal recovery components relevant to CHIME [9, 29, 32]. Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade 19 identified three superordinate categories and an emergent conceptual framework consisting of: 1) the recovery journey’s thirteen characteristics, 2) five recovery processes and 3) recovery stages. Stuart, Tansey and Quayle 32 highlighted the CHIME framework of recovery and four new topics, including difficulties, therapeutic input, acceptance and mindful awareness, and returning to, or desiring normality. Noteworthy, there is the new element’s emphasis on obstacles. Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade 19 agree in their expansive definition of recovery that it typically incorporates elements of the struggle. Difficulties are characterised by uncertainty and disempowerment; contradiction; loss and negative life changes; financial concerns; co-occurring substance abuse and mental illness; and stumbling, struggling, and suffering. Additionally, the systematic review and meta-analysis by Van Eck, Burger, Vellinga, Schirmbeck and de Haan [9] reported a small to medium relationship between some components of CHIME: connectedness, hope, and empowerment and clinical recovery.

Additionally, two reviews reported recovery as a process. Jose, Lalitha, Gandhi and Desai 30 mentioned recovery as process orientation, including continuous, non-direct, journey, strenuous, outcome oriented, and staged processes. In addition, the personal recovery process was viewed as 1) multidimensional and personalised, 2) slow and gradual, 3) transition from experiences of self-estrangement to self-consolidation, 4) change in self, 5) not all participants went through all stages, 6) non-linear social, 7) beyond symptom control and medication compliance, 8) has positive features that the experience of illness has brought on [35].

3.3. Recovery as an Outcome

Two studies described recovery as an outcome. The first study showed outcomes of recovery encompassed 4 areas as follows: 1) self-orientation, including understanding and accepting self, going back to normal self, gaining self-control, learning to manage self, achieving soft skills, and leading a meaningful life, 2) family orientation, including having relations, having responsibility, and productive social life, 3) social orientation, including social connectedness, social inclusion, effective communication, leadership roles, and economic resources and 4) illness orientation, including symptom-free state, improved functioning, back to normal, illness understanding and acceptance, and absence of treatment [30]. The second study stated that outcomes of personal recovery are bounced back to normal, be in self-control, and having a vision [35].

3.4. Recovery Components

The review by Clarke, Lumbard, Sambrook and Kerr 31 explained six main components including connectedness, sense of self, coming to terms with the past, freedom, hope, and health and intervention, while Ellison, Belanger, Niles, Evans and Bauer 34 presented 17 components of personal recovery framework by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) which comprises of 1) individualised and person-centered, 2) Empowerment, 3) hope, 4) self-direction, 5) non-linear/many pathways, 6) strengths-based, 7) Respect 8) Responsibility, 9) Peer support, 10) Holistic, 11) Addresses trauma, 12) Relational, 13) Culture, 14) Health, 15) Home, 16) Purpose, and 17) Community.

Table 2 summarised the crucial, intense and repeated elements from ten reviews as connectedness, hope, identity, meaning in life, empowerment, and difficulty (CHIME plus D) combined with content analysis of conceptualisation in Table 1. The authors were able to come up personal recovery definition as follows “Personal recovery among persons with schizophrenia, is defined as “the ability to live life on an individual's feelings, thoughts, and behaviours that one believes in the possibility of redefining the sense of identity, self-autonomy, meaningful life, a sense of hope, and better control over psychotic and affective symptoms. Persons with schizophrenia can overcome and be satisfied with their experience of stigma or negative life changes, maintain personal responsibility to act in introductory social functioning, have relationships, willing to help others, and be able to achieve overall well-being by accepting the support and being part of the community of choice which may be with absence or presence of mental health issues.”

Table 2.

| Master Theme/Dimension/Refs. | Prominent Subthemes/keywords |

|---|---|

| Connectedness [19, 29, 31, 32] | Relationships; peer support and support groups; being part of the community; support from others. |

| Hope and optimism about the future [19, 29, 31-33, 35, 34] | Thinking about recovery is possible through hope-inspiring relationships; motivation to change; escaping from something undesirable; having dreams and aspirations; positive thinking and valuing success. |

| Identity [19, 29, 32, 33, 35, 34] | Restoring/ rebuilding or redefining a positive sense of identity; able to overcome the stigma. |

| Meaning in life [19, 29, 32, 35] | Meaningful life and social roles; having spirituality; Meaning of mental illness experiences; quality of life; able to rebuild life; meaningful life with social role and social goals. |

| Empowerment [19, 29, 32, 34] | Personal responsibility; able to control life; focusing on strengths of themselves. |

| Difficulties [19, 32, 33, 35, 34] | Disempowerment, ambivalence and contradiction, loss and negative life changes, financial concerns, stumbling, struggling, and suffering. |

4. DISCUSSION

In this scoping review on systematic reviews, all 10 studies summarised and conceptualised personal recovery among schizophrenia patients. Surprisingly, six out of ten reviews documented clinical and functional recovery aspects [9, 30-32, 34, 36]. In other words, mental health professionals accepted personal recovery as a new paradigm shift. They could not overlook the clinical and functional recovery paradigm, because better symptoms and functioning in schizophrenia people are the initial steps on the personal recovery journey [10, 37]. Congruently, there were studies that revealed clinical recovery mediated functional recovery and personal recovery [7, 11, 22]. Likewise, they conveyed that personal recovery does not exclude the possibility that people with schizophrenia still have a mental illness or undergo a relapse. Even if they are in the process during distress episodes, they can recognise personal growth and can start a new life again if they do not leave off learning to live with schizophrenia.

The recruited articles illustrated that “hope” was repeatedly reported in components defining subjective recovery. Existing literature highlighted that hope is central to personal recovery, because hope matters in any situation, it is a catalyst for change, drives other pertinent factors to work, and leads to action based on approach rather than avoidance motivation, and has positive goals, rather than trying to avoid negative outcomes [2, 38, 39]. Mental health providers instill hope in people with mental illness, which supports both good clinical and personal recovery outcomes. Moreover, difficulties are considered because the personal recovery process has become complex because of the undesirable impact of chronic diseases 16 and the difficulties surrounding maintaining hope [39]. Therefore, difficulties are a major part of the recovery process.

Another critical issue raised by Temesgen, Chien and Bressington [35] reviewed and concluded that subjective recovery was conceptualised as process and outcome. Three outcomes of recovery are as follows: firstly, “bounce back” refers to the ability to restore self-identity, self-autonomy, self-reliance, get back into life, and decrease or alleviate mental illness symptoms. Individuals also viewed reduced or eliminated reliance on pharmaceuticals to manage their symptoms as a sign of recovery, albeit this was not always the case [40]. Secondly, “be in self-control” refers to the ability to take responsibility in social and functional roles. Thirdly, “have a vision” refers to having hope and meaningful life. These themes are consistent with the Unity Model of Recovery (UMR), developed by Song and Shih [41], Song [42] and Song and Hsu [43]. Only this one personal recovery framework was established in Asia (Taiwan). They depicted the personal recovery process, outcomes, and stages of personal recovery which are congruent with Temesgen, Chien and Bressington [35] finding, which has been stated before. It consists of regaining autonomy, management of disability/taking responsibility, and a sense of hope.

Based on multiple reviews, personal recovery is a holistic concept, including the elements of outcome and process where none predominates the other and they go together on a recovery journey [7, 19, 35]. Addressing how to measure both the personal recovery process and outcomes is challenging. Various tools have been developed for evaluating them. This review found CHIME plus D to be an essential component of the personal recovery process. A previous study by Shanks, Williams, Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier and Slade [44] identified 12 tools to measure personal recovery, which focuses on aspects of recovery defined by the CHIME framework. However, as pointed out above, those 12 tools do not include items for measuring D (difficulties) elements. Therefore, it may be necessary to develop a new scale for additional D elements. However, the instrument “the Stages of Recovery Scale for persons with persistent mental illness” by Song and Hsu [45] to fully measure processes and outcomes covers both components of personal recovery.

Noteworthy are the studies conducted based on the western models, and a broader scientific evidence base is needed. Consequently, research from culturally (non-English speaking nations) different countries would serve to emphasise both underlying social and political assumptions about the nature of rehabilitation and the individualistic rather than the collective emphasis of existing models of recovery [29]. This knowledge gap is crucial because psychotic and affective symptoms of schizophrenia may be alleviated by a culturally relevant interpretation and therapy for the condition. In order to get a more global and inclusive conception of recovery from schizophrenia, future research in this field should investigate the variables/factors and outcomes in low-resource settings and among underrepresented ethnic groups [45].

4.1. Implications for Nursing

It is highly recommended that mental health nurses consider personal recovery during the treatment. Involving the comprehensive aspect would help nurses to assess the schizophrenia problem during the recovery period. It would bring a new paradigm of schizophrenia nursing intervention. The personal recovery concept is also essential in the mental health and psychiatric nursing curriculum by focusing on nursing care with patient-centered alignment with personal recovery conceptualisation.

CONCLUSION

Based on the findings, personal recovery operational definitions were extracted and clearly defined from the patient's perspective. The majority of conceptualizations identified connectedness, hope and optimism about the future, identity, meaning in life, empowerment, and difficulties (CHIME-D). These are key domains within personal recovery among schizophrenic patients. Each domain is neither equal nor dominant, but their combination is known to support an individual recovery journey. As a result, CHIME plus D categories are crucial to the endpoint of nursing care, so future work should focus on supporting mental health providers, people with schizophrenia, and communities to be knowledgeable about CHIME plus D categories. In addition, the ability of mental health nurses to develop, adapt, adopt, and evaluate tools and nursing interventions should be expanded, so that they can support CHIME plus D among people with schizophrenia in order to use along with the clinical and functional recovery concepts to fulfill and achieve the recovery process and outcome completely. Also, developing a proper scale to measure might help nurses to improve and plan nursing care for them.

However, all selected studies were conducted in developed countries. Hence, future research is needed in developing countries and minority ethnicities in order to investigate whether the concept can be fully adapted or modified following culture. Moreover, it can lead to evoke the strategic overview, which considers developments across the mental health care system in each country.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Conceptualization J.T., J.Y.

Data curation J.T.

Funding acquisition J.Y., J.T.

Methodology verified the scoping review methods J.Y., J.T.

supervision J.Y., P.U.

Writing – original draft J.T.

Writing – review & editing J.T., J.Y., P.U.

Critical, discussed and contributed to the final manuscript J.T., J.Y., P.U.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines and methodologies were followed.

PRISMA checklist is available on the publisher’s website

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of all articles are available within the reference.

FUNDING

This study was funded by 90th Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University, Rachadapisek Sompote Fund. Funder ID: GCUGR1125652074D.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper is part of the dissertation of Miss Jutharat Thongsalab, a Ph.D. student in the Faculty of Nursing at Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, entitled “Factors predicting personal recovery among persons with schizophrenia living in community, Thailand. Additionally, this research received the 90th Anniversary of the Chulalongkorn University Scholarship, Ratchadapisek Somphot Fund.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

PRISMA checklist is available as supplementary material on the publisher’s website along with the published article.