All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Factors Involved in Iranian Women Heads of Household’s Health Promotion Activities: A Grounded Theory Study

Abstract

We aimed to explore and describe the factors involved in Iranian women heads of household’s health promotion activities. Grounded theory was used as the method. Sixteen women heads of household were recruited. Data were generated by semi structured interviews. Our findings indicated that remainder of resources (money, time and energy) alongside perceived severity of health risk were two main factors whereas women’s personal and socio-economic characteristics were two contextual factors involved in these women's health promotion activities. To help these women improve their health status, we recommended that the government, non-governmental organizations and health care professionals provide them with required resources and increase their knowledge by holding training sessions.

INTRODUCTION

The motto “healthy women, healthy world” implies this fact that women play an important role in maintaining the health and well being of their communities [1]. In order to perform the caring roles, women must maintain and promote their level of health and well being [2, 3]. Women heads of household are among vulnerable groups in society who are faced with poverty, unsuitable economic status and multiple roles [4]. In many cases, they cannot preserve and promote their health. There are various definitions about head of household [5, 6] but in this study, head of household is defined as one of the family members who is responsible for the provision of entire or an important part of family expenditure or decision making about how to spend the income of the household. Head of household is not necessarily the oldest member of the family and can be male or female. Obviously, in single-person households, the same person is the head of household [7]. Exploring the family evolutions in the world reveals that the number of women-headed households has been increased in the past fifty years and there has been a steady increase in the number of women-headed households in developing countries [5]. Husband’s migration, divorce, separation, and widowhood are the most common causes of increase in the number of women-headed households [5, 6, 8].

Although there are some studies reporting that the health level of women heads of household does not differ from other women [5,9,10], other studies showed that women heads of household suffer from poor socio-economic circumstances and health problems i.e. high levels of stress and depression, drug abuse and low quality of life [11,12]. Some studies also showed that lone mothers are more likely to have long term illnesses and die more often than married mothers [13, 14]. In some cases, migration of husbands decreased the mental health of their wives [15]. Divorced, widowed and separated women are more likely to have problems in paying their medical bills than either single or married women [3].

Health promotion is a strategy that can help to reverse unequal health outcomes [16]. The goal of health promotion is to enhance physical and psychosocial health [17]. People can preserve and promote their own health by doing Health promotion activities [18]. Women heads of household are faced with health inequalities and must try to promote their health. But, health promotion is a complex phenomenon that is influenced by personal and social factors that vary widely among women [19]. A myriad of factors influences the type of activities in which persons engage, whether it is helpful or harmful to their health. Some of these factors are socioeconomic status, skills, culture, religion, and gender [20]. In order to understand how women heads of household improve their health, the context in which they live and the factors that are involved in their health promotion activities should be taken into consideration. Examination of social, political, economic, cultural and environmental factors is important to understand community health status and to explain underlying health disparities among different subpopulations [21]. Contextual factors, including the proportionality between the women and their environment, are very important in the formation or resolution of health problems [22].

Background in Iran

Iran, as a developing country, has a population of more than 75 million people, half of which (49.6%) are women [7]. Iranian women are leading different roles simultaneously in society including the role of a mother, a spouse and other social roles as well [23]. Iran’s constitution stipulates that the government should provide support for working women [24]. So, even though the domestic roles and family duties are not at all overlooked, Iranian women play a significant role in the social, economic, cultural and political flow of their country. Currently, women constitute 27 percent of the workforce and working mothers is a new phenomenon in Iran [25]. In Islamic societies like Iran, family plays a fundamental role in the health and soundness of society. Hence, Iranian women are considered as the axis of the family's harmony and tranquility [24].

Nevertheless, today Iranian women are experiencing a developing transition. They are now excelling in academic and managerial positions and are gaining ever-greater achievements. The transitional phase has led to a growing number of divorces, an increase in average age at marriage and a lower fertility rate as a result of employment and education among Iranian women. A majority of Iranian women (60%) who worked outside believed that a contradiction exists between outside employment and housekeeping. They preferred their traditional role as homemakers because of social obstacles [26].

An increase in the number of women who are employed and also maintain a family role showed that the combination of both roles was considered an important factor in Iranian women’s health. Gainful employment, physical exercise, and cultural and educational development are social bridges to Iranian women’s health. Social barriers to these women’s health include gender inequalities, burden of responsibility, and financial difficulties [26].

One of the most important roles accepted by some Iranian women is household headship. Despite of strong cultural-religious traditions and legal prescriptions [27], widowhood and increase in the number of divorces are two main reasons for the acceptance of household headship by Iranian women [28]. Among 21 million households in Iran, more than 2.5 millions are headed by women and the proportion of the women-headed households in Iran has increased from 9.5 percent in 2006 to 12.1 percent in 2011[7]. 15.8 % of women head of household work outside and less than 1% are jobseeker. This may be due to the availability of financial resources, issues related to household headship and lack of job skills [28].

Many studies have been conducted on women heads of household in Iran and most of them are quantitative research including reviews and cross-sectional studies and just a few studies have been carried out with qualitative methodology and have looked into the problem from these women’s perspective. These studies mostly focus on issues such as poverty, social problems and occupational status of these women and nothing has been done on their health promotion and the context in which it occurs [29-32]. Therefore, Iranian society suffers from dearth of context based studies on this issue, and it seems that qualitative research methods can really clarify factors involved in health promotion activities of these women. Knowledge about the Iranian women heads of households’ health promotion and the factors involved in it is very limited because special attention has not been paid to these women in the “Iranian women’s health profile” [33]. We aimed to explore and describe factors involved in the health promotion activities according to lived experience of Iranian women heads of household.

METHODS

This report is part of a more extensive research that served as the corresponding author’s doctoral dissertation. The philosophical underpinning of this study is based on symbolic interactionism [34]. Symbolic interaction provides a perspective for studying how individuals interpret objects and other people in their lives and how this process of interpretation leads to behavior in particular situations. Symbolic interactionism has significant potential to increase the understanding of human health behaviors [35]. The choice of the research methods basically depends on the nature of the problem that is being investigated. Grounded theory is a methodology that allows formulating orderly abstractions from the real life data [36]. According to the present study, which aimed at developing new theoretical knowledge in an unexplored area, we chose Strauss & Corbin (1998) approach to grounded theory as the method of data collection and analysis [37]. The qualitative method of grounded theory was chosen to capture the reality of the health promotion activities of women heads of households living in Iran.

In addition, this approach was selected because women’s health promotion activities take place in a multi-factorial environment and grounded theory focuses on identification, description, and explanation of interactional processes between and among individuals or groups within a given social context [37]. Grounded theory is rooted in symbolic interactionism [38] and is sets out by researchers to discover patterns of behavior among particular groups of people in specific contexts [39]. Grounded theory considers women's perceptions, attributions of meaning, relationships, caring responsibilities, and preferences for interaction in health care field and provides a broad lens for meaningful research into women's health issues [34].

Participants

Sixteen women heads of household who were residing in three cities of Iran participated in this study. The participants’ age ranged from 24 to 63 years with a mean age of 42±10.18 years. They had 0 to 5 children and were all under health services insurance coverage. Three of the participants were suffering from chronic diseases such as diabetes, coronary artery disease and renal failure. They were a woman head of household for 2-26 years with a mean of 10.06±7.26 years. Other characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Other Characteristics of the Participants

| Demographic Data | Number | |

|---|---|---|

| Occupation | Housewife | 8 |

| Working outside | 8 | |

| Education | Elementary | 8 |

| Diploma | 3 | |

| Associate degree | 1 | |

| Bachelor's degree | 3 | |

| Master's degree | 1 | |

| Marital status | Divorced | 9 |

| Widowed | 2 | |

| Jobless spouse | 4 | |

| Single | 1 | |

| Coverage by supportive organizations | Yes | 6 |

| No | 10 | |

| Housing type | Owner | 8 |

| Rental | 8 | |

| Kind of persons under headship | Healthy child + sick husband | 2 |

| Healthy child + sick child | 2 | |

| Healthy child + sick child + sick husband | 1 | |

| Healthy child + sick mother | 1 | |

| Healthy child | 9 | |

| Sick mother | 1 | |

Data Collection

We started data collection in December, 2010 and continued this activity until June, 2012. Data were generated by semi-structured interviews. We used purposeful sampling for the initial interviews and continued by means of theoretical sampling, according to the emerging codes and categories [37]. Sampling started from Iranian Welfare Organization (IWO) and then was extended to the participants’ home or workplace. Social workers in (IWO) introduced participants who were more cooperative to the researchers. Hence, researchers could carefully select appropriate respondents with different characteristics. The criteria for selection were women heads of household who had taken charge of their families for any reasons, and had at least one year of experience of household headship. After interviewing six women and coding the transcripts, the codes and categories related to social support, and remainder of money led the researchers toward interviewing several other key informants. Other key informants used were other women who were not under coverage of (IWO) for the purpose of filling the gaps. To achieve maximum variation of sampling, we recruited women with different demographic and socio-economic characteristics.

We explained the aim of the study and the research questions for each potential participant. As the participants consented to participate in the study, interview appointments were determined. For participants' convenience, we conducted the interviews at the time they felt their workload was lower and had enough time to be interviewed. We conducted interviews in a private room at their workplace, home or (IWO). Our interview guide consisted of grand open ended questions to allow the respondents to explain their own viewpoints and experiences as completely as possible. We began each interview with a broad number of questions such as “please tell me about your daily activities?”; “Can you explain what you do in a day?”. Later, the participants were asked to define ‘health’ from their viewpoints, to talk about the situations in which their health was in the highest or lowest level and to explain about the activities that they did to improve their health status. We also used follow-up questions and probing to capture a deeper understanding of the phenomenon under study. During the interviews, notes were made about the situation of the interviews and non- verbal signals from participants. We recorded the interviews by a digital sound recorder. The duration of interview sessions ranged from 20 to 80 minutes, with an average of 50 minutes, depending on participants' tolerance and their interest in explaining their own experiences.

Data Analysis

We analyzed data from the interviews using constant comparative method. Data collection and analyses were carried out simultaneously. Each interview was transcribed verbatim and analyzed before the next interview took place. In other words, each interview provided the direction for the next one. These helped researchers develop the interview guide over time. We stopped the process of interviewing when data saturation occurred. Data were considered "saturated" when no more codes could be identified and the category was "coherent" or made sense.

Open, axial and selective coding was applied to analyze the data [37]. During open coding, each transcript was reviewed multiple times and codes were generated from the respondent's words and the researcher's constructs. For example, the code “emotional support” was generated by the researcher from a respondents’ comments, “my sister is my closest friend and helps me in all my problems. She guides me in solving my problems and never disappoints me.” or the code “relying on God” was generated from respondents’ comments, “because I am alone and don’t have any companion, when I have a problem, I talk with God.” Codes that were found to be conceptually similar in nature or related in meaning were grouped in categories. The categories and codes from each interview were compared with other interviews in order to identify common links. Categories were related to their subcategories in axial coding. The focus of axial coding was on specifying a category in the context in which it had appeared. Coding occurred around the axis of a category, linking categories at the level of properties and dimensions. Analytical tools such as asking questions and making comparisons helped in finding the properties of each concept [37]. Selective coding, then, developed the main categories and their interrelations. If the researcher is simply concerned with exploring or describing the phenomena being studied, axial coding will complete the analysis. Hence, we stopped data analysis at this phase because the aim of the study had been accomplished. However, grounded theory, as the term suggests, seeks to go further. For this reason, we need to go on selective coding.

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness of this study is vested in Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) concepts of credibility, confirmability, auditability and transferability.Credibility was established through member check, peer check and prolonged engagement [40, 41]. After the analysis, we contacted five participants and gave them a full transcript of their respective coded interviews with a summary of the emergent categories to determine whether the codes and categories were consistent with their experiences. An expert supervisor and two doctoral students of nursing checked the study process. Prolonged engagement with the participants within the research field for a period of 19 months helped us gain the participants' trust and better understanding of their real world. Maximum variation of sampling (in terms of marital status, years of being household headship, occupational status, geographical place, etc) also enhanced the confirmability and credibility of data. This sampling strategy enabled us to carefully capture a vast wide range of views and experiences. We saved all evidences and documents securely to maintain auditability. We carried out a thick description of the context adequately so that a judgment of transferability could be made by readers [41].

Ethical Considerations

We obtained ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (date and code number: November 20, 2010; 250/524). An official permission was also obtained from (IWO) in order to conduct the study. Ethical issues were concerned with the participants’ autonomy, confidentiality and anonymity during the study period. We informed all participants about the purpose and design of the study and also the voluntary nature of their participation. We obtained informed consent from all participants in written and signed agreements for all the stages of the study.

RESULTS

We presented the findings related to factors which involved in the women heads of household’s health promotion activities in this paper. Our analysis and interpretation of data indicated that the remainder of the resources (money, time and energy) and perceived severity of health risk were two main factors, whereas women’s personal and socio-economic characteristics were two contextual factors involved in the health promotion activities of the participants (Table 2).

Factors Involved in Women Heads of Household’s Health Promotion Activities

| Main Factors | Remainder of the resources | Remainder of money |

| Remainder of time | ||

| Remainder of energy | ||

|

|

||

| Perceived severity of health risk | ||

|

|

||

| Contextual Factors | Personal characteristics | Age |

| Duration of headship | ||

| Spouse situation | ||

| Number and age of children/the other members under headship and their health status | ||

| Religiosity | ||

|

|

||

| Socio-economic characteristics | Social support | |

| Educational level | ||

| Occupational status | ||

| Financial status | ||

Main Factors

Remainder of the Resources

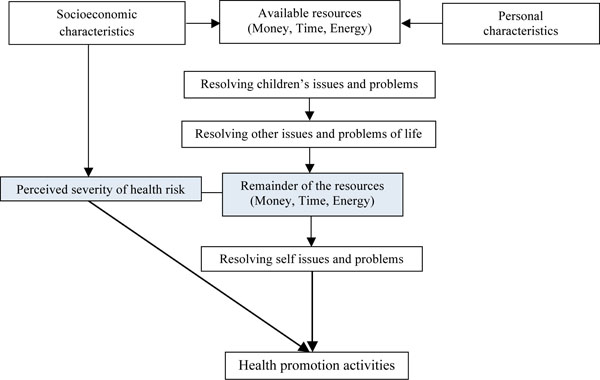

We found that the remainder of money, time and energy are the vital resources for health promotion activities of these participants. Based on their personal and socio-economic conditions, these women had access to a definite amount of money, time and energy. They tended to prioritize spending the available money, time and energy according to the issues and problems they encountered in their life and at the end, they would spend the remaining amount of each resource on themselves, particularly for their health. They tackled issues and handled problems related to their children and/or other persons under their headship, other issues and problems of daily life, and their own health problems respectively (Fig. 1).

Relationships between factors involved in women heads of household’s health promotion activities.

Remainder of Money

One of the important resources was the remainder of money. These women managed single-parent families hence enjoyed less financial resources. Most of them even took care of their sick children, spouse and parents too and consequently dealt with more financial problems. These women strived to prioritize the fulfillment of the headed individuals' financial needs through tolerating the tough conditions of life and being self-sacrificing.

“I have forgotten myself; I tolerate any hardship and I do not want to see my children depending on others” (Housewife and head of two healthy children, a sick child and her sick husband).

Financial problems forced these women to choose either the health of their children and the other family members under their headship, or their own health. Accordingly, they tended to be self sacrificing and opted for others' health and consent. In most cases, factors such as consumption of inadequate amount of protein like red meat and fish, using herbal drugs and over-the-counter medications as self-treatment, avoiding undergoing screening tests and periodical health status monitoring checkups, alongside hesitancy in referring to physician, and non-adherence to treatment threatened the women's health.

“I was suffering from Osteoporosis. A doctor gave me a drug which I had to take weekly. I took it for some time and then I stopped taking the drug. I couldn't afford it. My son was studying at university and his college fees were staggering” (Housewife and head of a sick child and two healthy children).

Remainder of Time

Another important resource for the health promotion activities of these women was the remainder of time. Most of the participants had multiple responsibilities towards their children and /or the other members under their headship so that they had to play the role of a father for their children, to take care of their sick family members, and even to work outside home simultaneously. They tried to primarily allocate more time to their children and /or the members under their headship which could potentially lead to ignoring themselves and jeopardizing their health.

“My friends suggested that I should go to park to take a walk twice a week; but I prefer to spend the walking time on my daughter” (Working and head of a sick child and a healthy one).

As their second priority, these participants devoted most of their time to other living issues such as their occupational matters.

“I do not have enough time to have lunch due to my job; I sometimes eat a banana or have my lunch at 8 p.m. that actually substitutes my dinner” (Working and head of a healthy child and a sick mother).

Ignoring the signs of poor health, irregular sleep, bad nutrition and lack of doing exercises were the outcomes of time shortage. However, there were a few women who devoted specific amount of time to take care of their self-related issues.

“Whenever I feel that I need to rest, I do not go outside the house; I avoid doing household tasks and try to get a thorough rest that day” (Working and head of a healthy child).

Remainder of Energy

The last resource which played an important role in health promotion activities of the participants was their remainder of energy. Several mental conflicts about different issues such as financial matters and also physical and psychological exhaustion related to various responsibilities were the factors that reduced the physical and psychological energy resources of these women and finally led to psychological disorders, sleep disorders and failure at performing health-promoting behaviors such as exercise and healthy nutrition.

“The fact that you ought to take care of some persons, sometimes drains all your energy and leads to lack of proper sleep, exhaustion, sadness and depression; I cannot bear to take charge of all these issues” (Working and head of a healthy child and a sick mother).

The women who had more liberty from these problems and more free times, tended to have more remaining energy both physically and psychologically and attempted to perform the activities that could improve their level of health status.

Generally, these women gave themselves third priority after their children/ members under headship and other life-related issues. So, depending on the adequacy of the three resources of money, time and energy, they carried out different health promotion activities.

Perceived Severity of Health Risk

The second main factor involved in these women’s health promotion activities was the perceived severity of health risk. These women could be on a continuum from lack of perceived severity of health risk to high perceived severity. Based on the extent of risk perception, they adopted certain actions to improve their health rapidly or gradually. For instance, one of the participants stated:

“Since I am prone to obesity, I eat food in a controlled manner. If I eat fatty foods in just one meal, I certainly control it in the next meal” (Working and head of a healthy child).

Whereas, another participant believed that:

“I think when I visit a doctor; a series of illnesses seems to suddenly appear in me; so I do not go to see the doctor at all. My kidneys are not working well; a doctor prescribed a pill thirty years ago which I still repeat taking it without further prescriptions” (Housewife and head of four healthy children).

In spite of having little amounts of remaining money, time, and energy, some of the participants gave their health a priority when they felt threatened. In other words, they were more self-health-oriented than child-oriented. It indicates that these women perceived the greatness of severity of their health risk which could have positive effects on their health promotion.

“It depends on the kind of expenditure and the problem; it is not on me or them to spend the money; priority goes towards the nature of the issue, the type of the incidence that has happened and its level of importance” (Working and head of a healthy child).

Contextual Factors

It is worth mentioning that the women’s personal and socio-economic characteristics were two contextual factors that had deep influence on the determination of available resources for these women. Also, some of these characteristics influenced the perceived severity of health risk of the participants.

Personal Characteristics

The woman's age, the duration of headship, spouse situation, number and age of children / the other members under headship and their health status, and religiositywere among personal characteristics of the participants.

It seems that increased age and long duration of headship as well as permanent headship (widowhood and being divorced) provide the women with better social, financial and cultural situations and enhance their adaptation as a result. Hence, these women had more resources of time and energy as a result of better time regulation and higher psychological energy and could perform activities to improve their health status.

“If I suffer from health-related problems, I certainly address it. Now, after divorce, I take care of myself more often; but before that, I had so much intense preoccupations that I was not able to think of myself and my own wellbeing” (40-year-old, divorced and household head for 10 years).

Some of the participants whose husbands were ill or in prison were temporary head of household. They had a sense of confusion, experienced intense psychological and social pressures and had a sense of self-forgetfulness.

“When I see that the father of the family is sick and has to stay at home all the time, and when I look at my needy children at the same time, I feel more and more exhausted” (26-year-old with a husband suffering from hepatitis B).

The participants also stated that having more children or persons under their headship, and also having small or sick children, further reduce their available money, time and energy and ultimately fewer resources remain for themselves.

“Since all of my three children are very small, taking care of them is too difficult for me and I cannot take care of my own health” (25-year-old and head of two healthy 10 and 7-years-old children and a 5-year-old child suffering from mental retardation).

It also seems that having religious beliefs decreases women’s stress and anxiety and as a result increases their psychological energy which has a positive effect on their health and wellbeing.

“I say to myself, if I have any problems, God is here with me and He listens to me and helps me tackle my problems” (working and head of a child).

Socio-Economic Characteristics

Social support, educational level, occupational and financial status were among socio-economic characteristics of these women.

Most of the participants stated that receiving social support (e.g. financial support, guidance, hope and motivation) from their families and friends could increase their access to resources of money and energy so that they could save more for their health. Health insurance had a key role in decreasing the medical expenses and increasing the available money.

“Social security insurance is very supportive for me and I cannot improve my health without it” (Working and head of a healthy child).

Educated and employed participants could earn more money, so they had less health problems. However, working outside home brought about less time and energy for these women that could negatively affect their health.

“I like walking, but I do not have enough time because of my job” (Working and head of a healthy child).

Participants’ statements make it known that the more educated women had more information about health-related matters and therefore had higher perceived severity of health risk. Moreover, employed women believed that contact with different colleagues in their work place will lead to their receiving useful information about health issues and a high perceived severity of health risk.

“Because I am an employee, I receive many health-related matters from my colleagues. They provide me with useful information” (Working and head of a healthy child).

All in all, regarding the personal and socio-economic characteristics of the participants, some were not faced with shortage of money, time, and energy; so they would have enough remainder of resources to improve their own health after giving priority to their children and all life-related issues. Some health promoting activities in this group of women included: having a healthy diet and a regular exercise program during the week, performing cancer screening tests (pop smear, mammography), regular dental check-ups and going to doctor as the minor symptoms appear.

DISCUSSION

We designed the present study to help us improve our knowledge about factors involved in Iranian women heads of household’s health promotion activities.

Our findings indicated that the remainder of resources and the perceived severity of health risk were the main factors and women’s personal and socio-economic characteristics were the contextual factors involved in the health promotion activities of the participants.

Individuals interpret social situations and respond in a way that they suppose is appropriate [42]. They construct the world external to themselves by their perceptions and interpretations of what they conceive that world to be [35]. Because of their different roles, women heads of household in this study had more interactions with social world and interpreted and perceived it differently. Their perception and interpretation of their life situations and the available resources led them to prioritize the issues and resolve the problems sequentially. Depending on the remained resources and the perceived severity of health risk, they opted for healthy and unhealthy behaviors. In other words, these women adopted certain decisions and selections in terms of the facilities, limitations and socio-cultural expectations which could protect their families on one hand, and care about their own health on the other hand.

Since most of the participants had poor access to financial resources, and they even had to allocate the money to their children or the members under their headship, a little amount of money remained for them; as a result, they were compelled to select unhealthy behaviors. Other studies also have shown that women heads of household are confronted with poverty and lack of financial resources [43, 44]. They have fewer resources to deal with health problems, and consequently are more likely to become marginalized and vulnerable [45]. When there are limited resources, women heads of household have a tendency to sacrifice themselves so that their children can have a better future [46]. It can cause health problems such as malnutrition, weakness, fatigue, and lack of full recovery from the disease [47, 48]. Nonetheless, it seems that not all women heads of household are faced with financial problems and it is required examining the inner household conditions to understand their financial vulnerability.

Having multiple roles as parent, caregiver, employee, and household headship, most of the participants did not have enough time to allot to their own health and they preferred to spend their own time on their children and the members under their headship or other life-related issues. There are two competing approaches to women’s multiple roles. The positive approach includes the ‘role enhancement hypothesis’ which discusses that multiple roles have psychosocial benefits for women through increased social support and self-esteem, whereas negative approach includes the ‘role strain hypothesis’ which mentions that pressures and demands related to multiple roles may exhaust women’s personal resources and negatively affect physical and mental health [49]. But results of this study revealed the negative effects of multiple roles of these women on their health and health-promoting activities. Malnutrition, lack of mobility and inattention to the symptoms of disease were among these negative effects. It is believed that internal distribution of resources in households headed by women is more ‘child-oriented’ and these women are faced with increased demands placed on their time and energy [50]. Lone mothers have multiple simultaneous commitments as a breadwinner and as a mother that can increase their stress levels and lead to poor health [51]. Normative female gender role responsibilities such as child care and housework can lead to decreased participation in physical activity [52]. Female gender roles may also make it difficult for women to give their own health a priority. Even women living with a chronic illness have difficulty taking care of their own health and self-care needs because of the demands and needs of others [53]. Women with full-time jobs worried about neglecting their children and having role strain and employment tensions. They reported more negative health problems and less social support, and the single ones mainly complained about caring for their old sick parents [26].

Decreased levels of psychological and physical energy in women heads of household occurred due to their mental involvement with different life-related problems, multiple roles and prioritizing their children and other members under their headship which finally resulted in lack of motivation, hopelessness, depression, anger, sleep disorders and a lot of other health-related problems. This issue led to lack of participation or limited participation of these women in health-promoting activities. It has been shown that time and energy commitment related to multiple roles can lead to role strain that have potential effect on health promoting behaviors by neglecting screening practices and avoiding from health promoting activities such as exercise and good nutritional practices [54,55].

Our findings demonstrated that the perceived severity of health risk among these women could differ from lack of perceived severity of health risk to high perceived severity. Risk is perceived and interpreted differently by different people and depends on ‘people’s beliefs, attitudes and feelings as well as the cultural and social dispositions they adopt towards hazards and their benefits. Risk perceptions are influenced by the individual’s recognition of the risk as familiar and amenable to modification, its association with clear benefits and impacts, the frequency of contact with the proposed risk, and external visibility of the risk [56]. According to health belief model, the greater the perceived risk, the greater will be the likelihood of engaging in behaviors to decrease the risk [20]. This is what prompts the women heads of household to avoid unhealthy behaviors and motivates them to adopt health promoting behaviors. Unfortunately, sometimes the opposite is the case because many of these women believe that they are not at risk or there is a low risk of susceptibility.

We indicated that a number of personal and socio-economic characteristics are involved in determination of money, time and energy available to the participants. Therefore, the characteristics inside each household should be addressed to a better perception of the conditions these women deal with. These conditions could provide a suitable or unsuitable environment for health-promoting activities. It seems that social support as one of the important socio-economic characteristics can to some extent compensate for the shortage of available resources by providing the required emotional, informational and instrumental support [57]. It is believed that emotional support through boosting self confidence and coping skills can make up for lack of psychological energy to some degree because of its stress buffering effects. Furthermore, providing informational support through health consultation can facilitate health promoting activities. Instrumental support would also be beneficial by providing money, job, insurance or other facilitations that can save time. Social support through changing life style and providing the required resources can generally influence health behaviors and help individuals develop and maintain healthy behaviors [58].

We showed that more educated women have a higher perceived severity of health risk. This could lead to conscious decision making about their health and therefore increases the likelihood of engaging in health-promoting behaviors. Also, the working women heads of household’s perception about the severity of the health risk was higher. It seems that working outside home and its related informational support have increased women heads of household’s perception of the severity of risk. It is believed that social activities may transmit health promotion information, increase perceived health risk and enhance motivation to engage in healthy behaviors [59].

Implications for Practice

Several implications for practice can be drawn from this study. Findings from this study suggest that the remainder of resources is one of the main factors involved in health promotion activities of women heads of household. Constitution of Iran puts emphasis on fulfilling the needs of women heads of household and other vulnerable populations [60]. So, governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) should consider providing them with required resources. Perceived severity of health risk is another main factor which affects health promotion activities of women. Hence, women’s health care nurses and family nurse practitioners should increase women’s knowledge and facilitate easy access to information about health-promoting life style by holding training sessions. Moreover, motivational counseling may be a critical intervention towards increasing motivation and social support for health promoting activities in such women. Women heads of household have multiple roles as parent, caregiver, employee, and household headship. Women’s Health care nurses and social service providers should learn about women’s roles in their individual clients and, in particular, how they can be developed to increase women’s health and disease self management. We showed that personal and socioeconomic characteristics have an enormous influence on the determination of resources and perceived severity of health risk. Therefore, women’s health care nurses need to be able to better identify and monitor these characteristics in order to provide such women with unique care.

We hope that our findings provide new insight for public health nurses, women’s health nurses, family nurses, policy makers in women’s health fields and health education programs. Also, these findings suggest useful insight for public health practitioners and researchers working in similar contexts like Middle East countries.

Research Implications

The present study was conducted on women heads of household with various personal and socioeconomic characteristics. A similar study including only divorced women, women working outside home, women having chronic illness or women living in rural areas may further explicate factors affecting their health promotion activities. Our participants were selected from three cities in center of Iran. It is probable that women from other parts of Iran share different experiences. So, additional researches within other cities with different socio-cultural background will help us provide a pool of accumulated data related to factors involved in health promotion activities of these women. Also, this inquiry is from the Iranian women heads of households’ perspective. Women in others areas may have different views, or may have similar experiences. Therefore, additional research studies are needed to further enhance our understanding of the factors involved in health promotion activities of these women in other countries.

Theoretical Implications

Philosophical root of this study is symbolic interactionism and we showed that women heads of household are faced with many socio-economic problems related to their health promotion. We propose that other nurse researchers take a new path focusing on other theoretical perspectives such as feminist and critical social theory to conduct women’s health research in this area.

CONCLUSIONS

We found that the remainder of money, time and energy and the perceived severity of health risk were the main factors involved in Iranian women heads of household’s health promotion activities. These women tended to allocate their available resources primarily to their children and the members under their headship and then to all life-related issues. As a result, few resources would remain for their own health; so they opted for health-promoting activities to a little degree. We found that the women’s personal and socio-economic characteristics were also the two contextual factors that influenced the availability of resources and the perceived severity of health risk in these women.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all the women who shared their rich and invaluable experiences to this study. We offer our heartfelt thanks to Center for Nursing Care Research affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences for financial support of this study. (This study has been approved at this research center as a research plan, (Proposal numbered 12475)). We would also like to express our sincere gratitude to Nancy Woods at the University of Washington for her insightful comments and valuable guidance.