All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Abstract

Epidemiologic data indicate that chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Patients with poorly managed COPD are likely to experience exacerbations that require emergency department visits or hospitalization—two important drivers contributing to escalating healthcare resource use and costs associated with the disease. Exacerbations also contribute to worsening lung function and negative outcomes in COPD. The aim of this review is to present the perspective of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in terms of providing the pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic modalities needed to treat current and prevent future exacerbations. Major respiratory guidelines recommend treatment of acute exacerbations with short-acting bronchodilators, oral corticosteroids and antibiotics, as appropriate. Supplementary oxygen and/or ventilatory support may also be beneficial to selected patients. Treatments to minimize the risk of future exacerbations should include maintenance pharmacotherapies, risk-reduction measures (e.g. smoking cessation, influenza and pneumonia vaccinations), pulmonary rehabilitation, self-management support and follow-up care.

INTRODUCTION

The 2010 Year of the Lung Declaration [1] made by the Forum of International Respiratory Societies was designed to increase awareness and action on respiratory conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Without interventions to cut risks, deaths from this widely prevalent, underdiagnosed, preventable and treatable condition (caused mainly by smoking and possibly less well-recognized risk factors) are projected to increase by more than 30% over the next decade [2-4]. The increasing airway obstruction, lung hyperinflation and physical activity limitations characteristic of stable disease progression are attributed primarily to a heterogeneous mixture of lung-structural abnormalities that may vary among individuals [5]. Exacerbations or worsening of symptoms, such as chronic cough, sputum production and dyspnea, punctuate the natural history of COPD and account for most of the health and financial burden associated with this disease [6]. These costs have been estimated to be as high as US$7,757 per exacerbation [7], with the largest component of the total costs of COPD exacerbations typically resulting from hospitalization. Although the costs can vary, they are associated with the severity of the exacerbation. Indirect costs have rarely been measured, but these resource-associated financial consequences of COPD exacerbations are likely to contribute substantially to overall costs. In addition, mortality rates are high, reaching 40% at one year in those individuals needing ventilatory support and up to 49% by three years following hospitalization for an acute exacerbation [5].

Evidence from the literature suggests that there is a high-risk, eight-week window of possible recurrence following an initial exacerbation [8] and a high-risk subpopulation who experience frequent exacerbations (≤6-month intervals; >3-per year) [9]. Results from the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) [10] study suggest that there is a frequent-exacerbation phenotype of COPD that is independent of disease severity. These patients have faster lung function decline and worse health-related quality of life compared with patients who have infrequent exacerbations [9]. Overall, the classic view of exacerbations as random events has been replaced by the recognition that the future risk of an exacerbation can be correlated to a history of past exacerbations [6]. In addition, the likelihood of a second event may be related to therapy used for an initial exacerbation [11] or non-resolution of the systemic inflammatory response [12]. Acute exacerbations occur more often in winter [13, 14] and accelerate disease progression [6].

The increasing presence of physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) in medical specialty, internal medicine and underserved settings [15] makes it likely that these healthcare providers will serve as important contacts for patients experiencing exacerbations. In an era where medicine requires collaborative multidisciplinary problem-solving to deliver affordable, quality care, it is important that all healthcare providers, including NPs and PAs, effectively manage patients with COPD during chronic, stable periods and accurately diagnose and treat acute exacerbations to improve patient outcomes. Recent reports have highlighted the important role of nurse-led management programs in improving patient outcomes [16-19]. This review focuses on interventions in outpatient and inpatient settings and addresses important areas where healthcare providers can play a role in preventing or delaying exacerbation recurrence.

DEFINITION

There is no clear consensus on the definition of COPD exacerbations across all settings as a result of the wide heterogeneity of clinical presentation and disease progression [20], although exacerbations can be stratified as mild, moderate, or severe according to the symptomatic criteria first proposed by Anthonisen et al., in 1987 [21]. These criteria by 1 of 3 symptoms: increased breathlessness; increased sputum volume; new or increased sputum purulence, are divided into mild (1 symptom), moderate (2 symptoms) and severe (1 symptom with at least 1 additional feature, including: upper respiratory tract infection in the previous 5 days, fever without other cause, increased wheezing or cough, or a 20% increase in respiratory or heart rate compared with baseline).

Cross-study differences in exacerbations reflect to some extent the differences in definitions used and classifications of these events [5, 22, 23]. In general, symptom- or healthcare utilization–based definitions are used. A symptom-based definition which is widely accepted and incorporated into key guidelines (e.g. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease GOLD [5] and American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society [ATS/ERS] [22]) is “an event in the natural course of the disease characterized by a change in the patient’s baseline dyspnea, cough and/or sputum that is beyond normal day-to-day variations, is acute in onset and may warrant a change in regular medication in a patient with underlying COPD”[5]. Healthcare utilization–defined exacerbations, such as any hospital admission with a primary diagnosis of COPD including those related to COPD, bronchitis or (in some cases) asthma by any physician in emergency departments, offices or hospital, can be treated as one episode if the interval between adjacent contacts is less than 14 days [24]. Such definitions have been used as a clinical endpoint in some major trials [23], since, in the absence of daily diaries to record symptoms, they are more readily recalled.

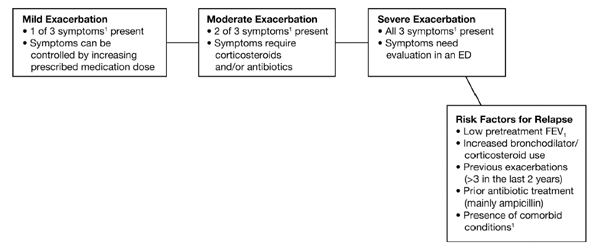

The GOLD guidelines [5] focus on appropriate antibiotic selection in further classifying exacerbations, whereas ATS/ERS [22] stratifies exacerbations according to the need for healthcare utilization. A composite system for ranking exacerbations according to their degree of severity is shown in Fig. (1) [5, 21, 22].

Ranking of COPD exacerbations and risk factors for relapse.a

The lack of consensus means that NPs and PAs, as well as physicians, working in primary care report lack of awareness and use of COPD guidelines, and also feel a need for correct information related to epidemiology of the condition and the different benefits of available treatment strategies [25].

ETIOLOGY

Respiratory infections are associated with the majority of COPD exacerbations and their severity [26], including viral (Rhinovirus spp., influenza) and/or bacterial (Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Enterobacteriaceae spp., Pseudomonas spp.) infections of the tracheobronchial tree. However, a clinically significant number of exacerbations occur without the presence of detectable infection [26]. Furthermore, most patients have evidence of bacterial colonization, and potentially pathogenic organisms can be recovered from the respiratory tract secretions of virtually all patients with COPD [27]. Non-microbiologic causes include environmental irritants and lack of adherence to prescribed treatments, including medications and oxygen therapy, and failure to participate in pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) [22]. Oxidative stress may be an important mechanism that contributes to the amplified inflammatory response characteristic of COPD exacerbations [5].

Exacerbation frequency may be independently associated with progression of disease, a history of exacerbations, poorer health related-quality of life, elevated white blood cell counts and a history of heartburn [10]. Understanding the mechanism underlying exacerbation frequency may lead to improved preventive therapies.

DIAGNOSIS

The lack of an agreed upon (or consensus) classification as to COPD exacerbations, and signs and symptoms common to other conditions, complicates diagnosis. Differential diagnosis is thus important to correctly identify an exacerbation of COPD in respect of possibly confounding history and physical signs. Radiography can assist in ruling out pneumonia and pneumothorax, while electrocardiography is useful to eliminate diagnosis of right ventricular hypertrophy, arrhythmia, or ischemia [5].

However, in regular practice, NPs and PAs can play a leading role by administering screening questionnaires at presentation. These should be used routinely to assess risk factors and medical history, including genetic predisposition to underlying COPD [28]. The ATS/ERS guidelines suggest a number of elements to assist in the evaluation and diagnosis of exacerbations, based on clinical history, physical findings, and laboratory diagnostic procedures [17]. In addition, the GOLD guidelines recommend monitoring symptom patterns and appropriateness of current pharmacologic treatments. Symptom patterns of particular importance are increased dyspnea and more “winter colds,” prior exacerbation or respiratory disorder–related hospitalization, and presence of comorbidities that may restrict activity [5].

Measurement of arterial blood gases is important in determining the severity of an exacerbation [5]. This can be enhanced by monitoring blood oxygenation via pulse oximetry, with change from baseline established by prior lung function and laboratory tests in patients known to have COPD, and assessing severity of symptoms (e.g. change in sputum volume or color, use of accessory respiratory muscles, paradoxical chest wall movements, onset of peripheral edema, somnolence, cyanosis and signs of right heart failure) in patients experiencing exacerbations [5]. Although spirometry is recommended to diagnose and stage stable COPD cases (Table 1) [5], pulmonary function testing is not recommended for patients in the midst of an exacerbation, as it shows only a weak correlation with arterial blood gases.

Disease Staging and General Symptomsa

| Stage | FEV1/FVC | FEV1 Predicted | General COPD Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| I (mild) | <0.7 | ≥80% | Chronic cough or sputum production may be present (but not always) |

| II (moderate) | <0.7 | 50% ≥FEV1 <80% | Exertional dyspnea develops (cough and sputum production sometimes present); some patients may have frequent exacerbations |

| III (severe) | <0.7 | 30% ≥FEV1 <50% | Greater exertional dyspnea, fatigue and repeated exacerbations |

| IV (very severe) | <0.7 | FEV1 <30% or 50% predicted plus chronic respiratory failure | Symptoms worsen; potentially life-threatening exacerbations |

FEV1=forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC=forced vital capacity; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

a Please refer to reference [5] as cited in text.

Specific systemic biomarkers are beginning to be identified in association with exacerbations and their recurrence; for example, patients who experience frequent exacerbations have been found to have significantly higher levels of serum IL-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) during their recovery period after an exacerbation, and high serum CRP concentrations measured 14 days after an index exacerbation can predict recurrent exacerbations within 50 days [12]. Other known risk factors for relapse are listed in Fig. (1) [5, 21, 22].

Treatment

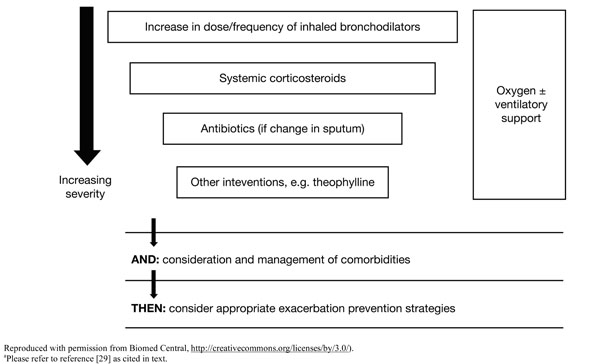

Nurse practitioners and PAs should work collaboratively with the healthcare team, patient and family members to achieve evidence based, short and long term outcomes in patients with COPD including prevention and early and effective management of exacerbations. A treatment algorithm encompassing pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic strategies is presented in Fig. (2) [29]. Milder exacerbations may respond to an increase in the dose and/or frequency of existing bronchodilator therapy [5]. It is important to emphasize that exacerbation severity does not always equal severity of the underlying disease (e.g. individuals with mild COPD may experience an acute sentinel event whereas the opposite may be true for patients with severe disease) [29].

Treatment algorithm for exacerbations.a

Fig. (2) [29] shows both treatment of acute exacerbations (using short-acting bronchodilators (example in Table 2) [5, 23, 30] and other agents to prevent relapse and rehospitalization) and post-exacerbation management (using maintenance pharmacotherapies (examples in Table 2) [5, 23, 30] and non-pharmacologic strategies to prevent future exacerbations and interrupt pulmonary decline).

Examples of COPD Pharmacotherapiesa

| Drug Class (Example) | Recommended Purpose (Drug Class) |

|---|---|

| Increase Dose and/or Frequency for Acute Exacerbations | |

| Short-acting β2-agonist | Can be used during all stages of the disease |

|

|

| Long-Acting Agents (for prevention of future exacerbations) | |

| LABA | Maintenance therapy beginning in GOLD II; more effective than short-acting agents alone |

|

|

| Long-acting anticholinergic | Maintenance therapy beginning in GOLD II; more effective than short-acting agents alone |

|

|

| LABA/inhaled corticosteroid combinations | Can be used for the treatment of patients with severe and very severe COPD |

|

|

1 Indicated to reduce exacerbations.

2 Indicated to reduce exacerbations in COPD patients with a history of exacerbations.

LABA=Long-acting β2-agonist; GOLD II=Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease stage II (moderate COPD); COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Acute Exacerbations

Increasing the dose and frequency of short-acting bronchodilators is a necessary first step in the treatment of acute exacerbations, with the addition of oral corticosteroids for individuals unresponsive to the first intervention [29]. Changes in sputum characteristics may necessitate the addition of antibiotics appropriate to the causative bacterial pathogen (e.g. anti-pseudomonal β-lactams may be needed if Pseudomonas spp. are present, as is sometimes the case with severe exacerbations) [5]. However, it should be noted that in many cases the etiology cannot be confirmed, due to colonization, and thus even when bacteria are cultured from samples, this may not prove to be beneficial prior to initiating treatment. However, when a causative organism can be identified, individual, local and regional antibiotic-resistance patterns, as well as drug availability, side effects and treatment duration are important considerations in the selection of an antibiotic [5, 29]. Thus far, the prophylactic use of antibiotics for prevention of exacerbations has not been tested in real-world settings. Additional interventions, such as theophylline, may be required in selected cases where the clinical response to treatment is incomplete [29]. However, the use of theophylline is subject to the need for close monitoring of serum levels because of known side effects and pharmacokinetic interactions with other medication. An increased dosage may be required in patients who continue to smoke and in patients taking medications that are eliminated hepatically. A dosage reduction is necessary in patients with hepatic failure or congestive heart failure, and in those patients receiving, among other medications, macrolide antibiotics, quinolone antibiotics, allopurinol, oral contraceptives, and histamine H2-receptor blocking agents [31]. Furthermore, monitoring serum theophylline levels following dosage adjustment is important for maintenance of a therapeutic drug level.

Criteria listed in Table 3 [5] are grounds for prompt admission to the hospital or intensive care unit, where local resources regarding personnel, skills and equipment for managing acute respiratory failure are available. Supplemental oxygen therapy is necessary at any stage in the presence of new or established hypoxemia and/or respiratory failure (Fig. 2) [29], with a goal of improving baseline blood oxygenation to a partial pressure level of at least 60 mm Hg at sea level and to produce a saturation level of oxygen of at least 90% for an uncomplicated exacerbation [5]. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation is considered to be effective in reversing acute respiratory failure in selected patients with elevated carbon dioxide and no other life-threatening comorbidities who are able to cooperate with healthcare providers [22]. A need for oxygen and/or ventilatory support, premature onset (aged <40 years) or severe disease, precipitous health decline and new comorbidities (Fig. 2) [29] are all reasons for referring patients to a specialist [22].

Indicators for Hospital or ICU Admission for Patients with Exacerbationsa

| Hospital Admission1 |

|---|

|

| ICU Admission |

|

1 Local resources should be considered.

ICU=intensive care unit.

a Please refer to reference [5] as cited in text.

PREVENTION OF FUTURE EXACERBATIONS

Although long-term, multifaceted care is a goal for all patients with COPD, it is of particular importance to those who have recovered from acute exacerbations. To prevent relapse, the GOLD guidelines [5] suggest spirometric evaluations 4-6 weeks after hospitalization for an acute exacerbation; however, the utility of these results in terms of modifying therapy awaits evaluation in randomized, controlled trials. Generally, risk-reduction measures (e.g. smoking cessation counseling and appropriate vaccinations), maintenance pharmacotherapies, PR and self-management support form the key components of long-term management to prevent future exacerbations. Self management plans for COPD are available at: http://www.lunguk.org/supporting-you/Publications/copd_self_management_plan and http://ww w.livingwellwithcopd.com/ password is copd.

Clinicians should understand principles of collaborative disease self management. Of significant importance in COPD is working with the patient and medical team to support long-term smoking cessation, influenza and pneumococcal vaccination, effective use of optimal medication, such as long-acting bronchodilators, patient understanding of prevention, and prompt reporting of symptoms suggestive of exacerbation or lung infection and regular clinician follow-up.

Approved long-acting β-agonists (LABAs) or long-acting anticholinergics (LAACs), administered individually or in combination therapies (Table 2) [5, 23, 30], have been shown to be effective for the maintenance treatment of stable COPD. Together with results from two separate megatrials [23, 30], the exacerbation-reducing benefits of the LABA/inhaled corticosteroid combination, salmeterol/fluticasone, and the LAAC, tiotropium, suggest that these medications can reduce disease progression. More precisely, salmeterol/fluticasone and tiotropium can potentially decrease exacerbation frequency or prevent future exacerbations, thereby reducing the need for healthcare utilization.

In addition, PR, including patient education on disease self-management strategies and monitored, supervised exercise, has been shown to improve dyspnea, exercise capacity and quality of life, and has been shown to reduce healthcare utilization in persons with chronic lung disease.

There is emerging evidence regarding the role of PR in patients recovering from an acute event, particularly if sustained over the long-term [5].

Self-management plans, whether independently administered or incorporated as part of PR (e.g. physician-directed action plan, including prescriptions of relevant medications and strategies for optimizing daily activities), empower patients to recognize symptoms and provide a guide as to appropriate next steps. Regardless of the established long-term plan, patients should be examined within at least four weeks following hospital discharge [22].

The goals of the initial follow-up and regular treatment reviews are primarily to monitor disease progression, symptoms and overall health status of the patient (Table 4) [5]. However, regular provider—patient meetings also present opportunities for the NP/PA to establish a rapport with patients and better understand their personal and health-related goals. It has been established that treatment plans incorporating, for example, individualized diet and exercise programs; education around pharmacotherapies, disease, inhalation techniques [32] and relaxation practices, can improve the mental and physical well-being of patients. Regular follow-up also allows the healthcare practitioner to note early signs of exacerbations and educate patients about the importance of symptom reporting (e.g. as part of a self-management plan) and self-management.

Follow-Up and Regular Review of Patients with Exacerbationsa

| Risk Factors |

|---|

|

| Disease Progression and Patient Health Status |

|

| Treatment Review |

|

ADL=activities of daily living.

a Please refer to reference [5] as cited in text.

ROLE OF NPs AND PAs

The management of COPD exacerbations is variable in critical [33] and primary care [34] settings, in spite of recommendations from major respiratory guidelines [5, 22]. Delegating collaborative patient evaluation, management and follow-up in an orchestrated manner by NPs and PAs in these settings may improve the consistency and quality of care in patients who are prone to or experiencing an exacerbation. Historically, supervised NPs and PAs have provided similar quality of emergency care to patients with acute respiratory disease as physicians have provided [35]. A vital part of expanding NP and PA involvement in all aspects of exacerbation management is to increase their knowledge base, the positive effects of which are shown in the results from the Stemming the Tide of Antibiotic Resistance (STARS) [36] educational initiative, which included NPs as participants. In addition, Sridhar et al., [37] reported that nurse-led care for patients who were hospitalized with an acute exacerbation, including PR, self-management education and an action plan, resulted in reduced primary care consultations and mortality rates.

CONCLUSIONS

Expanded knowledge of treatment components could positively affect healthcare-provider management, and prescribing practices and attitudes in the treatment of exacerbations of COPD. Further studies are needed to assess the impact of real-world interventions involving NPs and PAs on preventing or delaying exacerbation recurrence in patients following recovery from an index event.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Chris Garvey has received consultation fees from Boehringer Ingelheim/Pfizer and Sepracor and is a speakers’ bureau member for Boehringer Ingelheim. Gabriel Ortiz has been a consultant to Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough/Merck, Sepracor and TEVA, and is a member of the following speakers’ bureaus: Phadia US/Quest Diagnostics, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough/Merck and TEVA.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Manuscript preparation, including medical writing assistance which was provided by Zeena Nackerdien, PhD, of Envision Scientific Solutions, was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Pfizer Inc. The article reflects the concepts of the authors and is their sole responsibility. It was not reviewed by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Pfizer Inc, except to ensure medical and safety accuracy.