All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Implementation of Crisis Resolution Home Treatment Teams in Wales: Results of the National Survey 2007-2008

Abstract

Background:

In mental health nursing, Crisis Resolution and Home Treatment (CRHT) services are key components of the shift from in-patient to community care. CRHT has been developed mainly in urban settings, and deployment in more rural areas has not been examined.

Aim:

We aimed to evaluate CRHT services’ progress towards policy targets.

Participants and Setting:

All 18 CRHT teams in Wales were surveyed.

Methods:

A service profile questionnaire was distributed to team leaders.

Findings:

Fourteen of 18 teams responded in full. All but one were led by nurses, who formed the main professional group. All teams reported providing an alternative to hospital admission and assisting early discharge. With one exception, teams were ‘gatekeeping’ hospital beds. There was some divergence in clients seen, perceived impact of the service, operational hours, distances travelled, team structure, input of consultant psychiatrists and caseloads. We found some differences between the 8 urban teams and the 6 teams serving rural or mixed areas: rural teams travelled more, had fewer inpatient beds, and less medical input (0.067 compared to 0.688 whole time equivalents).. Most respondents felt that resource constraints were limiting further developments.

Implications:

Teams met standards for CHRT services in Wales; however, these are less onerous than those in England, particularly in relation to operational hours and staffing complement. As services develop, it will be important to ensure that rural and mixed areas receive the same level of input as urban areas.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, health care systems are adapting to changes in the balance between acute and chronic conditions and the subsequent realignment of the equilibrium and equipoise between the burden of treatment relative to the burden of illness. This shift in the pattern of disease, from single episode and ‘cure’ to long-term management and ‘care’ has stimulated a reappraisal of the professional boundaries between doctors, with skills in acute medicine, to nurses with specialist areas of knowledge, caring skills and smaller case loads [1-3], particularly in community mental health nursing [4].

Crisis resolution and home treatment (CRHT) services have been in development for the past 25 years and rose to prominence in the UK in the 1990s, following the successful development of home treatment models globally [5]. The CRHT model has evolved gradually from earlier home treatment models, shaped by developments in the USA and Australia, which are now prominent in most Western countries [6].

CRHT services have been rapidly implemented in England and Wales with a 409% increase in spending in real terms between 2002-3 and 2006-7. However, wide variation in the components of a CRHT service persist, attributed in part to regional variations in need [7].

BACKGROUND

Development of CHRT services is a response to the increasing evidence that mental health services may be better provided with early intervention within people’s own homes and a recognition of the fact that this method of service delivery costs less than existing hospital based care. CRHT services aim to provide a realistic and safe alternative to hospital treatment for individuals of adult working age and beyond who are suffering from severe and enduring mental illness. This can be achieved by: assessment and treatment of mental health needs, including new prescribing, at home wherever possible; providing rapid response; gatekeeping hospital beds; working intensively with individuals for a short period of time and facilitating early discharge for individuals who have already been admitted to hospital.

There is international consensus on the advantages of providing crisis services. In the UK, these have formed a key part of mental health strategy, including the English National Service Framework for Mental Health and subsequent policy guidance [8, 9], and the Welsh priorities and planning guidance [10, 11]. CRHT services can: reduce the number of hospital admissions; reduce the length of stay on inpatient units; increase cost effectiveness and provide more satisfactory care for service users and their families, with no significant difference in the rates of suicide or violence [5, 12-14].

Mental health policy and policy guidance in Wales prior to this survey [10, 11] had demanded the introduction of Crisis Resolution Home Treatment (CRHT) teams to serve the adult population. Despite this, there appeared to have been a varying degree of implementation of CRHT services across Wales.

CRHT services are relatively new and have largely been developed in urban areas [15]. Existing models of implementation are based upon urban models, and, as with all aspects of public health, further work is needed to explore their relevance to and feasibility in non-urban areas [16].

THE STUDY

Accordingly, we surveyed all CRHT teams in Wales to evaluate the service’s progress towards the target set by WAG in 2004, (Service and Financial Framework target 17), that all health communities must put in place mental health CRHT services by 31st March 2006 [10]. The expected outcome was reduction in total mental health bed days for adults of working age by 5% in 2006-7 and 25% in 2007-8. This was compared against policy guidance issued a year later [11] (see Fig. 1).

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

The purpose of this survey was to:

- audit and generate a baseline understanding of CRHT services in Wales between September 2007 and March 2008;

- explore how a largely urban model was being implemented in a small country with mixed pockets of rural population;

- examine whether services have met WAG (2004, 2005) [10, 11] targets (above), and where difficulties have arisen in achieving this;

- elicit what the teams felt their goals should be for the future.

PARTICIPANTS AND SETTING

Wales is a small country with a population of approximately 3 million people [17]. All CHRT teams in Wales were surveyed. This accounted for all major urban areas of Wales, but excluded some rural areas as they had not yet developed CRHT services in response to WAG policy.

METHOD

A service profile questionnaire, with a mixture of closed and open questions, was developed by the All Wales CRHT Network, involving the majority of CRHT services across Wales. This survey was discussed, developed and piloted with the network over several months. The network was also used to identify any other CRHT services in Wales. Any secondary mental health team that provided a service which could respond to individuals in crisis, within the guidance of WAG (2005) [11] policy, was invited to complete a service profile. These were distributed via email for return via email or post. Reminders were sent to those who had not responded within six weeks.

Teams were asked to describe whether they operated within an urban, rural or mixed area. There are no universally accepted criteria for rurality [16]. The criteria used for this survey were those adopted by the national survey of CRHT teams in England [15], which were adapted from Periman et al. (1984) [18]. An “urban” area was defined as a city or town with a population of at least 50,000; a rural area as one with no town of 10,000 or more and less than half the population living in towns/villages of 2500 or more; and mixed areas as meeting neither of the above criteria.

Staff were categorised by professional group and, for nurses, pay band. Establishment figures were measured as whole time equivalents (wtes) with 1.0 wte being equal to 37.5 hours per week. This was compared to recommendations made by the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health [19], a UK charity that undertakes research, policy work and analysis to improve mental health practice and other public services.

This service evaluation was undertaken as an audit, and was approved as such by the NHS Trust Research and Development Department. Accordingly, the local Research Ethics Committee felt that ethical approval was not required.

ANALYSIS

Data were entered into into the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Il., USA) for windows, version 16 and described [20].

Open questions were asked around some areas of practice where there appeared to be no clear established patterns in Wales, such as:

- “What arrangements does the Team have for medical cover, both day to day and in relation to responsibility for the Team caseload?”

- “How are you evaluating the work of the Team?

- Does the evaluation draw directly on the experience of users of the service and people that support them?”

- “What do you feel is particularly effective about the team?”

Responses to open questions were examined by content analysis to check the frequency and distribution of certain responses [21].

RESULTS

Of the 18 teams in Wales, 15 replied, response rate 84% and 14 (78%) responded in full. No questionnaires were excluded as incomplete, although not all respondents were able to answer all questions.

What the Teams are Able to do

In terms of providing the core components of a CRHT service, all teams were able to provide an alternative to hospital admission for those experiencing acute mental health difficulties. All teams provided intensive contact with service users and, where appropriate, carers for up to six weeks. Fourteen teams (93%) acted as “gatekeeper” to acute inpatient services, rapidly assessing individuals with acute mental health problems and referring them to the most appropriate service. All teams were involved in the early discharge of inpatients.

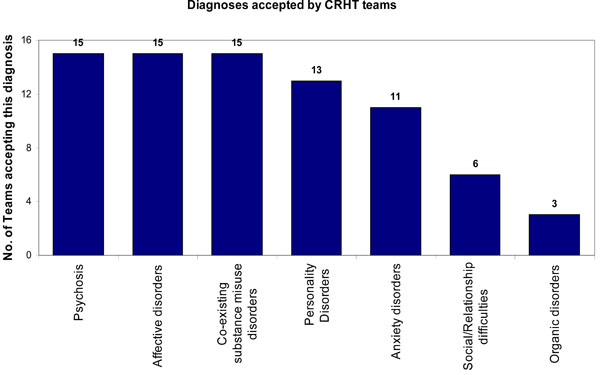

All teams accepted referrals for individuals experiencing psychosis, affective disorders and coexisting substance misuse disorders. There were variations around other presentations. Most teams would accept individuals experiencing anxiety disorders and personality disorders. Most would exclude social or relationship difficulties, a primary diagnosis of substance misuse, or organic disorders (Fig. 2).

Inclusion criteria for CRHT teams.

All 15 teams had crisis beds available to them. Thirteen teams (87%) had access to inpatient units for overnight admissions. One of these could also access a single bed within a local authority residential unit when a crisis bed was required as an alternative to using the traditional inpatient unit. The other two teams (13%) shared access to a dedicated crisis house and a crisis recovery day unit, operating seven days a week, staffed by a multidisciplinary team. Only three other teams (20%) had access to day hospital services. For any additional needs, other teams accessed existing community mental health teams, which are secondary mental health community services, typically operating within the hours of 9-5 Monday to Friday.

Impact of the Teams

Teams were asked how they assessed their impact and if their data indicated that they had been effective since their introduction. Eleven teams (73%) routinely used patient satisfaction surveys, although it is not clear how these are distributed and collated. Eight teams (53%) routinely gathered data to assess their team’s impact on admissions, using: numbers of referrals; referral sources; assessments offered; numbers accepted by team; length of team intervention; numbers admitted; length of stay on ward; assessments for avoiding or for offering an alternative to admission and facilitating early discharge. Eight teams (53%) reported that their data indicated that they had been effective in reducing admissions to acute psychiatric beds. Three teams (20%) felt they were providing a rapid response to urgent referrals. Eight (53%) stated that they had improved “whole systems working” that had improved the service users’ experiences.

“Urbanicity” of Teams

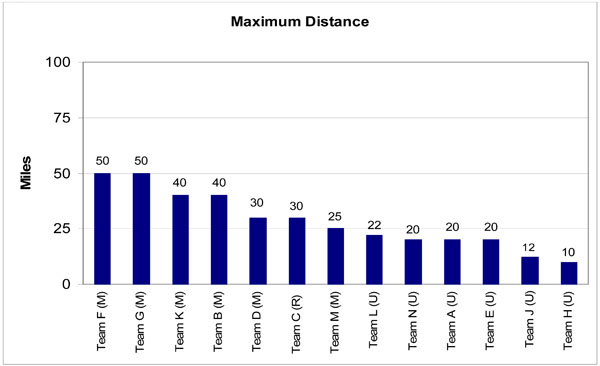

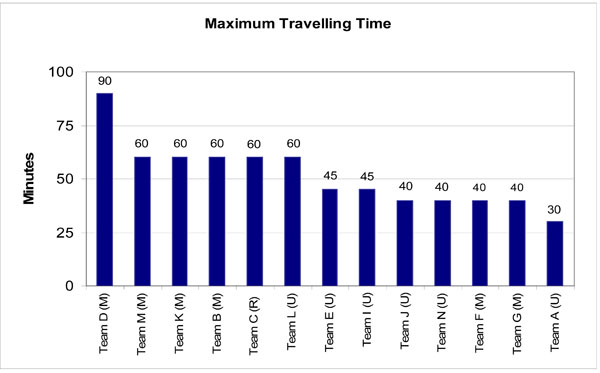

Of the fifteen teams who responded, eight teams (53%) operated in urban areas, six teams (40%) in a mixed urbanicity area, and one team in a rural area. Only nine teams completed information on the approximate square mileage of their area. The smallest area reported was 40 square miles and the largest 987 square miles. Urban teams covered smaller areas (Fig. 3).

The measure of urbanicity is indicated by urban (U), mixed (M) and rural (R).

All urban teams travelled less than 26 miles to visit a service user. This could increase to 50 miles (Fig. 4a) for mixed or rural areas. The mean maximum travelling time to visit a single client was 52 minutes (SD 17), median 52.5. With one exception, urban areas report less travelling time than rural/mixed areas (Fig. 4b).

Maximum distances travelled by teams.

Teams’ minimum travelling times.

Urban teams had an average of 29.8 inpatient beds available to them, mixed teams 22.8 beds and the one rural team had 16 beds. Urban teams appeared to have a greater number of beds accessible, however one urban team also had the lowest (11).

Operational Hours of Teams

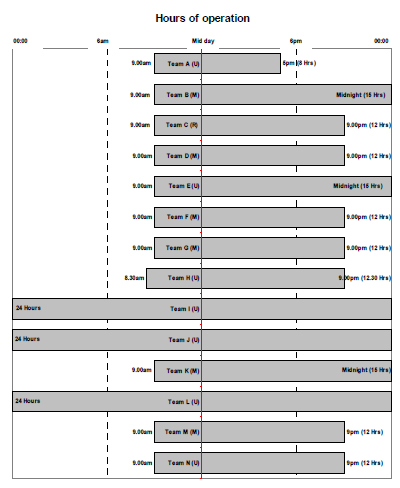

Eight teams (53%) operated a twelve hour service generally between 9am and 9pm; there were variations to within 1 hour. Three teams (20%) operate from 9am to midnight, and three (20%) a 24 hour service. Ten (67%) stated that their out of hours services were offered by other teams, most commonly the on-call psychiatrist. One stated that a telephone service was available from inpatient units (Fig. 5).

Hours of operation.

Team Structure

Fourteen teams (93%) reported their establishment; the fifteenth was still in development. Two teams shared staff and it was unclear to what extent their roles and responsibilities were dedicated to CRHT work, therefore, they were removed from the calculations. Of the twelve teams considered, six (50%) met the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health guidance of minimum team of 10-11 wte in urban areas [19], four met Department of Health [9] recommended team of 14 wte clinical staff, excluding psychiatrists. The three oldest established teams in the country had not developed to meet Sainsbury minimum recommended guidelines. They also lacked full multidisciplinary establishment (Table 1).

Description of Staff Employed

| Establishment of Teams | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRHT | Urbanicity | Consultant Psychiatrist | Other Medic | Social Worker | Psychologist | Occupational Therapist | Nurse Band 7 | Nurse Band 6 | Nurse Band 5 | Support Worker (Including Other) | Administrator | Establishment (Exc. Psychiatrist and Admin) |

| Team A | Urban | 0.6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5.6 | |||||

| Team B | Mixed | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 4 | 2 | 7.2 | |||||

| Team C | Rural | 1 | 2.5 | 5 | 8.5 | |||||||

| Team D | Mixed | 1 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 9 | ||||||

| Team E | Urban | 1 | 3 | 3 | 7 | |||||||

| Team F* | Mixed | 3.5 | 1.6 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 14.1 | |||||

| Team G* | Mixed | 0.5 | 1.6 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 11.1 | |||||

| Team H | Urban | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 10 | |||||

| Team I | Urban | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.4 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 17.4 | ||

| Team J | Urban | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 15.5 | ||||

| Team k | Mixed | 1 | 5 | 3 | 9 | |||||||

| Team L | Urban | 2 | 2 | 0.6 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 18.6 | |||

| Team M | Urban | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 15 | |||||

| Team N | Urban | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1.5 | 12 | |||||

* Report that they ‘share’ 11.1 team members. Figures expressed as whole time equivalent.

The mean number of whole time equivalents per team was 11 (SD 4), median 9.5, range 5.6-17.4. This was related to the size of population served by the team but not the time and distance travelled. This establishment figure excludes psychiatrists and administration staff in order to provide a figure for the clinical team for comparison with Sainsbury guidance [19].

Multidisciplinary Input

Most CRHT team members were registered nurses (49.8%, 73.3 wte), followed by nursing assistants (31.1%, 46 wte) (Fig. 6). Nurses and nursing assistants therefore accounted for 80.9% (119.3 wte) of teams’ total establishment. Social workers accounted for 5.1% (7.6wte) of teams overall and occupational therapists accounted for 2.3% (3.4wte). Seven teams (47%) reported no social worker and eight teams (53%) reported having no occupational therapist. There were no differences between urban and other teams. Three teams (20%) had only nursing professionals.

Skill mix by discipline.

The Input and Role of Psychiatrists

One team had a dedicated full time consultant psychiatrist; another had 0.5wte dedicated consultant psychiatrist. Only urban teams had any dedicated consultant psychiatrist input, and they were more likely to have a multi disciplinary establishment. Four of eight urban teams had medical input, compared to one of 6 mixed/ rural teams: urban teams have a mean of 0.688 medical wtes, and mixed/rural teams 0.067. Six teams (40%) have access to some dedicated medical input between 9-5 Monday to Friday. All other teams were able to draw on external medical expertise, such as community mental health teams or inpatient units. Welsh government policy [11] dictates that teams should have access to a multi disciplinary team as a minimum, and it appears that all teams comply with this.

Caseloads

The mean maximum caseload was 16.8 clients (SD 5.3), median 15.5, range 7-27. The maximum caseload for any team was 27. This was the maximum caseload size allowed at any time, and occurred in an urban area. The smallest caseload was 7 in a mixed area. Urban teams had a mean maximum caseload of 18. Mixed teams had a mean maximum caseload of 14. The one rural team identified a maximum caseload of 20 (Table 2). The three teams in development could not be considered.

Team Caseloads and Staffing

| Team | Maximum Caseload | Total WTE Per Team |

|---|---|---|

| Team A (U) | 12 | 5.6 |

| Team B (M) | 14 | 7.2 |

| Team C (R) | 20 | 8.5 |

| Team D (M) | 7 | 9 |

| Team E (U) | 14 | 7 |

| Team H (U) | 16 | 10 |

| Team I (U) | 22 | 17.4 |

| Team J (U) | 15 | 15.5 |

| Team K (M) | 20 | 9 |

| Team L (U) | 27 | 16.6 |

| Team M (U) | 20 | 15 |

| Team N (U) | 15 | 12 |

Future Developments

Teams were asked to identify their goals for the next twelve months. All teams stated that they intended to develop further, consolidate their practice and develop new ways of working. Four teams (27%) identified that they needed to improve their early discharge role, and another four teams (27%) that they intended to employ more staff.

Teams were asked to identify the obstacles to further development towards full implementation of the Policy Implementation Guidance document [11]. Thirteen teams (87%) cited human and financial resources as the main obstacle to development. Two teams (13%) described problems with releasing staff from other areas within the local health community or using non-permanent staff. Three teams (20%) had no multidisciplinary (social workers, occupational therapists, psychologists) staff. One team experienced problems funding 24 hour services, and two (13%) with gatekeeping.

DISCUSSION

This survey reports a baseline review of CRHT services in Wales as they existed in 2007/2008 from the perspective of the CRHT managers and team leaders, and how these have been developed compared to national targets and guidance issued by the Welsh Assembly Government.

The WAG position prior to March 2009 was that “organisations must have developed Crisis Resolution Home Treatment services that provide a single point of contact to high quality services and meaningful advice directly from clinical staff” [22]. There were no robust systems in place for performance management, nor was policy prescriptive in what should constitute a CRHT service.

There were disparities in the CRHT services across Wales, and variations in team sizes and multidisciplinary input. Due to the diverse geography and demography of Wales teams may need to adapt to meet differing service needs. There were large variations in the areas covered by teams, their travelling times and distances. Overall, a trend has appeared for services operating within the hours of 9am to 9pm, which is congruent with WAG but not UK policy directives and guidelines.

Since the presentation of a report based on this survey [23] the Welsh Assembly Government [22, 24] introduced a system of performance management to ensure that CRHT services achieve their intended targets. These have been standardised as:

- providing a rapid response to urgent referrals (face to face assessment within four hours),

- gatekeeping 95% of all admissions to hospital between the hours of 09.00 to 21.00,

- providing a review within 24 hours of admission for 100% of admissions who had not been gatekept by the CRHT prior to admission,

- focussing on the target population (individuals with a severe mental illness, experiencing a crisis due to their mental illness).

- involvement with the individuals for up to six weeks.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

This survey encompassed all the CHRT services in one small European country. While some findings are similar to those reported in England, UK [15], their saliency to nursing services in other countries must be based on inference and practical adequacy. As with all cross sectional data, association does not imply causation, and the small sample size necessitates cautious interpretation of findings.

This survey has focused on distinct CRHT services; however there were three teams (20%) identified as being in development, with CRHT services being offered from existing CMHT teams. In consideration of the respondent burden, we were unable to gain full information on a number of issues, such as training needs, and interventions administered, and it is hoped that we shall be able to address this in future work.

A SERVICE IN DEVELOPMENT

At the time of data collection, CRHT services were not available in all parts of Wales. The WAG requirement to provide CRHT services throughout Wales had not been met. Additionally, whilst fifteen teams responded to the survey, three (20%) considered that were still developing a toward a CRHT service, and there have been further changes.

CRHT services in Wales have been in development since 2002. They appear to hold mixed views on their effectiveness to date, and the majority, thirteen teams (87%), indicated that lack of resources prevented them from achieving this. Most teams (13, 87%) stated that human and financial resources were the biggest obstacle to providing a robust service and this is supported by the evidence gathered on team establishments with limited involvement from psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers and occupational therapists. This is consistent with the results of the English survey [15]. There appears to have been a focus on developing CRHT services in urban areas since 2005 and there are now more CRHT services in urban areas than elsewhere, which is consistent with the picture in England provided by Onyett et al. [15].

While the government in Wales has demanded the provision of services between 09.00 and 21.00, English policy guidance [9] demands 24 hours services, which is consistent with recommendations made within the literature evidencing the use of CRHT services [5, 7, 19, 25].

The UK National Audit Office [7] notes that fully multidisciplinary teams, including dedicated input from consultant psychiatrists, are able to provide better quality of care and integration within mental health services. Despite this, teams in Wales have been developed primarily using the nursing profession. Nurses and nursing assistants account for 80.9% (119.3wte) of the total establishment measured. Consultant psychiatrists were significantly absent from teams. Only one team had a dedicated full time consultant, and another had a dedicated consultant psychiatrist 0.5wte. Seven teams (47%) had no social worker and eight (53%) no occupational therapist. Urban teams are more likely to have a multidisciplinary team; however all teams indicated that they could draw on multidisciplinary support from existing community services.

Guidance issued by the Department of Health [9] and Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health [19] suggests team sizes of 10-14 people for a population of 150,000. Of the teams surveyed only six (40%) were able to meet the minimum figure. These were in urban areas. CRHT services which cover more rural areas must also take into account the potentially long distances and travelling times within their establishment figures. There is currently no universally recognised method of accounting for the establishment needs of rural CRHT services, which suggests that further research is required, and geographical variation should be taken into consideration in future planning [26].

Most teams felt that they were able to provide the core elements of a CRHT service. All were able to provide an alternative to hospital admission, intensive home treatment for a period of up to six weeks and facilitate early discharge. Fourteen teams (93%) stated that they were able to gate keep hospital beds. The involvement of CRHT teams in Mental Health Act assessments is currently low with only three teams (20%) indicating that they are included as an integral part of the process. If CRHT teams are to act as a gatekeeper for inpatient services then this figure should be higher.

Alternatives to hospital admission are limited in Wales. Only two teams had access to a dedicated crisis house and one team had access to a crisis bed in a local authority funded residential unit. Teams have otherwise made use of existing service provision to provide alternative resources. This appears to support the view of the National Audit Office [7], that whilst alternatives to admission as well as home treatment can provide valuable support, their provision is inconsistent.

MEDICALLY UNDERSERVED LOCATIONS

Teams were staffed primarily by nurses. Growth in demand for medical care has outstripped the available supply of doctors in many areas of the UK [27] particularly economically deprived communities and unpopular specialities. Accordingly, nurses' roles are expanding to include delivery of complete episodes of care as envisaged in the NHS Plan 2000 [28]. Our study indicated that management of acute episodes of mental illness and gate keeping of acute beds has devolved to nurses: whether this may be viewed as recognition of burgeoning demand, cost-containment or a challenge to the hegemony of medicine is uncertain [29, 30].

Consultant psychiatrists, social workers and occupational therapists were largely absent from teams; however these professions were accessed from existing CMHT resources. Consequent difficulties in providing a multidisciplinary service require further exploration. Non-urban teams had no dedicated psychiatrists and fewer medical staff (0.067 wtes, compared to 0.688 wtes). This reflects the reduced accessibility of primary care and services associated with rurality in the UK [31], international reviews [32], and the USA [33]. Some problems, such as suicide in adults [34, 35], depression and anxiety [36], substance misuse [37], may be more prevalent in rural areas. Given the socio-economic profile of many clients of mental health services, and findings that rurality accentuates the effects of socio-economic disadvantage [32], this inequality of access to medical input is cause for concern.

|

Recommendations for Practice

Responses to this survey and wider reading indicated that in order for CRHT teams to focus on their core functions they should:

|

|

Recommendations for Research

Further review and audit to determine how services are being delivered should:

|

In medically underserved locations and unpopular specialities, clinical care is hampered by the ‘Inverse Care Law’ [38] (the more the clinical need, the fewer the doctors), and the ‘Inverse Interest Law’ [39] (the commoner the condition, the less the medical interest). Whether development of crisis teams staffed by nurses, practising autonomously, will erode or accentuate these inequalities in service delivery between urban and rural, rich and poor will need further investigation.

To date, there appears to have been limited success in applying a largely urban model of CRHT services to a small country with mixed pockets of population. Lack of resources was cited as the single biggest obstacle to achieving this, and non-urban teams were less well resourced. While the number of staff employed in each team reflected the population size, it did not take account of the increased travelling needed outside urban areas. While distance to hospital is crucial in some areas of medicine [40], further research is needed to explore the impact on acute mental health episodes.

Policy in England and Wales has, perhaps unsurprisingly, developed similarly; however there are some variations which reflect the differences between the two countries. Most notably, Welsh policy has not directed health care providers on the minimum establishment of the team in terms of core multidisciplinary input, team size, or hours of operation. Table 3 compares key elements drawn from the policies and compared with guidance issued by the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health:

Comparisons of Some of the Key Features of a CRHT Service

| Department of Health Policy Guidance [9] | Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health [19] | Welsh Assembly Government Policy Guidance [11] | Welsh Assembly Government Annual Operating Framework [22, 24] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gatekeep hospital beds | Yes | Yes: most or all admissions. | Yes | Yes. 95% of admissions. |

| Be multidisciplinary input as a core of the service, including a senior psychiatrist. | Yes | Yes | Yes, or have access to multidisciplinary staff. | Yes, or have access to multidisciplinary staff. |

| 24 hours services | Yes | Yes | 09.00-21.00 with an on-call system outside these hours. | 09.00-21.00 with an on-call system outside these hours. |

| Rapid response to referrals | Yes. Within one hour. | Yes | Yes. No target but refers to England being one hour. | Yes. For urgent referrals: provide a face to face assessment within 4 hours. |

| Suggested team size | 14 (excluding medical staff) for a population of 150,000. | 14 (excluding medical staff) for a population of 150,000. Minimum of 10-11 staff. | Not mentioned. | Not mentioned. |

| Focus on target population. | Yes. | Yes. | Yes. | Yes. |

| Time limited intervention | Yes but time limit not specified. Also notes that teams should remain involved until the crisis is resolved. | Teams should remain involved until crisis is resolved. | Up to six weeks. Also notes that teams should remain involved until the crisis is resolved. | Up to six weeks. Also notes that teams should remain involved until the crisis is resolved. |

| Facilitating early discharge | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes. |

CONCLUSION

This work has highlighted the need for practice developments (Box 1) and further research (Box 2) in relation to local geography. Worldwide, there is growing recognition that the key to improving health care for all citizens requires the expansion of nursing roles. In developing countries and the less affluent and more remote areas of developed countries, this necessitates nurses assuming new responsibilities, formerly the preserve of the medical profession.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper was presented at the All Wales CRHT Conference on 25th September 2008 and is based on a report to the All Wales Crisis Resolution Home Treatment Network.

We should like to thank the All Wales Crisis Resolution Home Treatment Network, and in particular Brahms Robinson of the Newport Home Treatment Team, for the work undertaken in developing the service profiles, identifying teams and assistance in gathering data for this survey. Mr. Emrys Elias, Senior Performance Improvement Manager (Mental Health), NHS Delivery and Support Unit, Wales, for his assistance in clarifying Welsh government policy. We should also like to thank Amorelle Jones and the Clinical Effectiveness and Audit Department within the mental health directorate of Hywel Dda Health Board for their assistance in collating the data.