All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Prevalence and Contributing Factors of Menstruation-related Absenteeism among Schoolgirls: A Systematic Review Meta-Analysis

Abstract

Introduction

Menstruation often causes dysmenorrhea, affecting 50–90% of women and impairing daily activities. Among schoolgirls, pain, poor menstrual hygiene management (MHM), and cultural stigma contribute to absenteeism. This review examined the prevalence, duration, and contributing factors of menstruation-related absenteeism among schoolgirls.

Methods

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library were searched to February 2025. Eligible cross-sectional studies on primary and secondary schoolgirls were screened and extracted by two independent reviewers. Outcomes included prevalence, duration of absenteeism, and association with maternal illiteracy. Random-effects meta-analyses were conducted using R 4.3.3.

Results

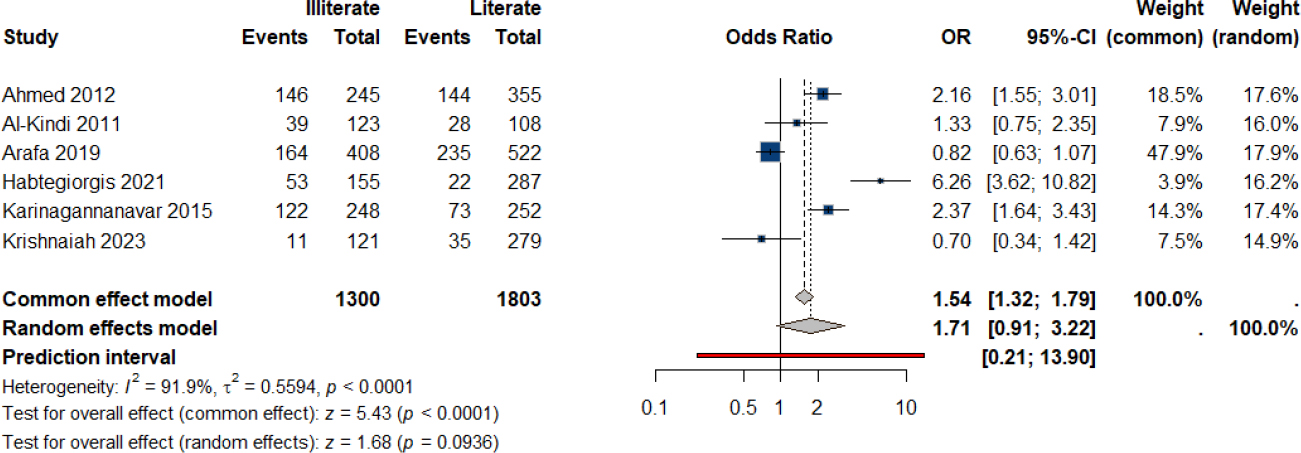

Fifty-four studies with 41,112 participants were analyzed. The pooled prevalence of menstruation-related absenteeism was 26.5% (95% CI: 21.98–31.89; I2 = 99.1%). Absenteeism was highest in girls with severe pain (42.32%) compared to moderate (13.14%) and mild pain (11.37%) (p < 0.0001). Mean absence duration was 1.93 days (95% CI: 1.63–2.28). Maternal illiteracy was associated with higher odds of absenteeism (OR = 1.71, 95% CI: 0.91–3.22) but was not statistically significant (p = 0.0936).

Discussion

Severe dysmenorrhea, inadequate MHM, and cultural restrictions are key drivers of school absenteeism. Infrastructure improvements and maternal education appear protective, but heterogeneity and inconsistent reporting limit generalizability.

Conclusion

Menstruation-related absenteeism remains a significant barrier to education for schoolgirls. Addressing pain management, hygiene infrastructure, and socio-cultural barriers is essential to improve attendance and equity.

1. INTRODUCTION

Menstruation is a biological process involving the periodic shedding of the uterine lining and typically occurs in cycles of 21 to 35 days [1]. Dysmenorrhea, or painful menstruation, is a common gynecological condition that affects 50% to 90% of menstruating women and can significantly cripple daily activities and quality of life [2]. It is classified as primary, occurring without underlying pathology, or secondary, linked to conditions such as endometriosis or fibroids [3]. The condition is associated with prostaglandin release, early menarche, family history, BMI, lifestyle factors, and psychological stress [4-7]. Management includes NSAIDs, hormonal contraceptives, and alternative therapies such as acupuncture and yoga, nonetheless, many women do not seek treatment due to stigma or lack of awareness [8-10].

Dysmenorrhea presents a substantial challenge specifically among primary and secondary schoolgirls, with reported absenteeism rates ranging widely due to menstrual pain [11, 12]. In Dysmenorrhea presents a substantial challenge specifically among primary and secondary schoolgirls, with reported absenteeism rates due to menstrual pain ranging widely [11, 12].

Inadequate menstrual hygiene management (MHM) is another factor in school absenteeism, as girls without access to sanitary products and proper facilities are more likely to miss school during menstruation [13, 14]. Beyond missing school, dysmenorrhea negatively impacts academic performance and quality of life [14]. Prior studies including undergraduate students were excluded to maintain the current review's clear focus on schoolgirls attending primary and secondary education [12, 15, 16].

Studies in Ghana and India demonstrated that poor sanitation and cultural taboos contribute to this issue in low-resource settings [15]. Cultural stigma further discourages attendance, with many girls fearing embarrassment or peer discovery of their menstrual status [16]. Limited education on menstrual health exacerbates these challenges [17]. In addition, anxiety about leakage and staining, combined with inadequate school facilities, further prevents girls from attending classes [15, 18].

Higher maternal education is linked to better MHM and lower school absenteeism among adolescent girls. In Ghana, girls whose mothers had secondary or higher education were more likely to practice good MHM and attend school during menstruation [14]. Educated parents provide better resources and knowledge, reducing stigma and fear. In contrast, lower family education contributes to misinformation and absenteeism, as seen in Indonesia, where girls from less-educated backgrounds were more likely to miss school due to a lack of menstrual health awareness [19]. Moreover, family support in the form of open family discussions about menstruation has led to lower absenteeism rates [20].

Previous meta-analyses on menstrual-related absenteeism have provided valuable insights into the prevalence and factors associated with this issue, but they have limitations in scope and focus. For instance, some studies have included a heterogeneous population [21, 22]. In contrast, our meta-analysis addresses these gaps by including a larger number of studies and focusing on schoolgirls. We analyze the prevalence and duration of absenteeism, the association between pain severity and absenteeism, and the effect of maternal literacy. This focused approach allows us to provide a more comprehensive and targeted understanding of menstrual-related absenteeism among schoolgirls. This study aims to comprehensively analyze the prevalence, duration, and contributing factors of menstrual-related absenteeism among schoolgirls.

2. METHODS

This review was constructed according to the formatting guide of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [23, 24].

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

The record retrieval process involved multiple phases. Initially, a broad search using generic terms was conducted across PubMed, Scopus, and Embase to identify preliminary articles. This was followed by a refined search strategy incorporating MeSH terms and relevant keywords, systematically applied to PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science. The specific search terms related to our review were as follows: (school* OR adolescen* OR student* OR class OR classes) AND (Menstrua* OR Mense*) AND (absen* OR attend* OR miss*). Our final search strategy was conducted in February 2025, using the detailed query. Finally, we manually searched through the references and citations of the retrieved records to find additional relevant studies.

2.3. Selection Process

To ensure a fair and unbiased selection process, two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of the available records based on predefined eligibility criteria. Identifying data such as author names were concealed. A third reviewer was available to resolve any conflicts between the two reviewers. After the initial screening, the same two reviewers independently assessed the full texts of the selected articles for eligibility, and they compared their findings to resolve any remaining disagreements.

2.4. Data Collection

Two independent reviewers extracted data from full-text articles into a shared Google spreadsheet, following a two-part process using a predetermined set of variables. In the first part, reviewers independently extracted baseline characteristics of participants, including participant age at menarche, current age, pain severity, duration of menstruation, family history, and maternal education level. In the second part, for analysis, they extracted data on prevalence and duration of absenteeism, and the prevalence of maternal illiteracy among absent and non-absent girls.

2.5. Outcome Measures

All continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. In studies where data were expressed in forms other than mean ± SD, we used the available formula from the Cochrane Handbook to convert them back into means and standard deviations.

2.5.1. Prevalence of Absenteeism

This outcome summarizes the results from schoolgirls who reported absenteeism during their periods since menarche. In addition, a separate analysis was conducted for studies that stratified absenteeism by the severity of pain (mild, moderate, and severe).

2.5.2. Duration of Absenteeism

We extracted the average number of days of absenteeism reported during periods expressed as mean±SD or other equivalent summary statistics.

2.5.3. Maternal Illiteracy

This outcome compares the prevalence of maternal illiteracy between girls reporting absenteeism vs those not reporting it during their periods.

2.5.4. Risk of Bias

Two different reviewers assessed the quality of all full-text articles, and conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer. The reviewers evaluated the methodical quality of all cohort studies using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Studies [25].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were carried out using R v 4.3.3 software. We used the meta package to determine the pooled prevalence, the mean duration of absenteeism, and the rate of maternal illiteracy between absent and nonabsent girls. Absenteeism was subgrouped by pain severity from eligible studies. Combined estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Statistical significance was determined by a p-value of less than 0.05. Heterogeneity among included studies was assessed using the I2 statistic, with an I2 above 40% and χ2p-value<0.1, indicating heterogeneity. The random effects model was used to account for heterogeneity. We implemented the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) to estimate heterogeneity (τ2), and the results were displayed on a forest plot, providing information about individual studies and the heterogeneity of the effect measure.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study Selection

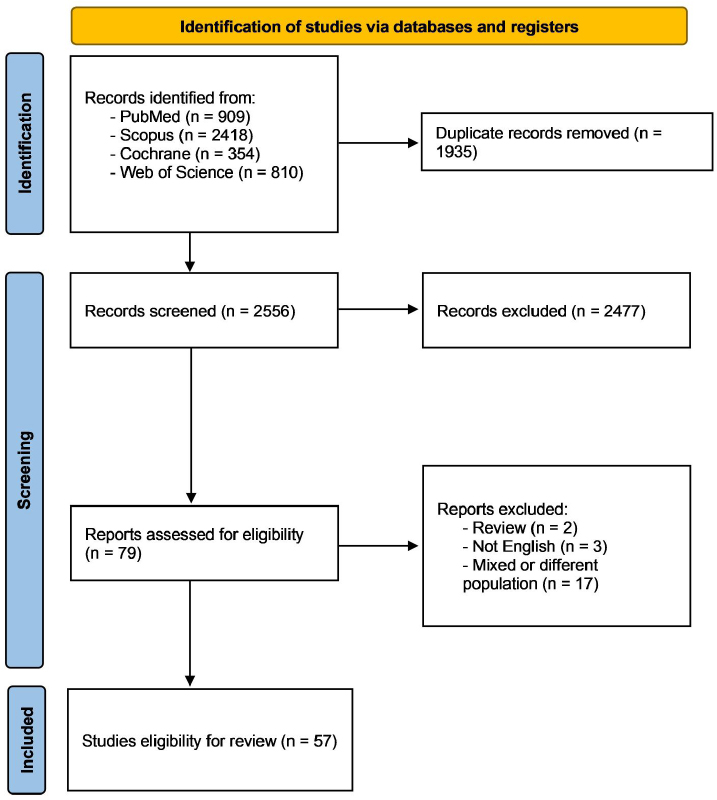

A systematic search across four databases yielded 4,491 records. After removing 1,935 duplicates, 2,556 unique records underwent title and abstract screening, excluding 2,477 entries. Full texts of the remaining 79 articles were assessed for eligibility, leading to the exclusion of three non-English publications, two review articles, and 17 studies that did not align with the target population. Ultimately, 57 articles met the inclusion criteria, with 54 providing adequate data for quantitative analysis. The flow diagram for study selection is shown in Fig. (1).

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

This review included 57 studies across 32 countries, spanning all different continents [13, 15, 17, 26-78]. The total number of schoolgirls involved in these studies was 46,222, and individual study sample sizes ranged from 20 to 4,202 participants. The majority of participants were from Asia (19,499), followed by Africa (12,014), Europe (6,463), North America (2,035), Oceania (6,037), and South America (174). The weighted mean current age of the schoolgirls across the 57 studies was 15.87 years, with a standard deviation of 1.62 years. The mean age at menarche was 12.70 ± 1.23 years. Data on pain severity was available in 15 articles. The weighted mean percentages for pain severity across these studies are as follows: mild pain was reported by 25.2% of participants, moderate pain by 39.8%, and severe pain by 35.0%. Considering the data for the duration of menstruation from 17 studies, menses lasted for an average of 4.6 ± 1.035 days. For detailed information about individual studies, refer to Table 1.

3.3. Risk of Bias

The methodological quality of each included cross-sectional study was assessed independently by two reviewers using the NIH Quality Assessment Tool. Studies were initially rated as 'good', 'fair', or 'poor'. Due to the nature of cross-sectional designs, four of the 14 NIH tool domains were deemed not applicable. For consistency, studies rated as poor due to these inapplicable domains were reclassified as fair. Full quality ratings are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Nonetheless, studies were rated as poor as four out of the 14 domains of the tool were inapplicable to cross-sectional design. When taken into account, all studies with poor quality would be rated as fair.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process.

| Author | Country | Number of Schoolgirls | Age | Age at Menarche | Pain Severity | Duration of Menstruation | Family History | Maternal Education | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD/Range | |||||||||

| Abd El-Mawgod et al. 2016 [26] | 1. Saudi Arabia 2. Others |

344 | 16.2 | 1 | 12.6 ± 1.04 | 1. Mild: 54 (21.1%) 2. Moderate: 106 (41.4%) 3. Severe: 96 (37.5%) |

1. 2–6 days 158 (61.7) 2. More than 6 days 98 (38.3) |

1. Yes: 168 (65.6%) 2. No: 88 (34.4%) |

NR | “Dysmenorrhea is common in the adolescent population in Arar city and leads to limitations in social and academic activities. In light of the public health importance of the social and academic limitations associated with dysmenorrhea, school administrators could play a vital role in this regard by incorporating dysmenorrhea and its treatment into health education activities and classes. Health education has to be supplemented by availability of other services such as consultation with the school nurse and school physician for consultation and drugs to alleviate pain.” |

| Acheampong et al. 2019 [27] | Ghana | 760 | 16.7 | 1.98 | 13.62 ± 1.256 | 1. Mild pain: 241 (35.4%) 2. Moderate pain: 223 (32.8%) 3. Severe pain: 216 (31.8%) |

1. <3 days: 62 (9.1%) 2. ≥3 days: 618 (90.9%) |

1. No: 489 (71.9%) 2. Yes: 191 (28.1%) |

NR | “The high prevalence of dysmenorrhea established reveals the magnitude of the problem in Shai Osudoku District. The adolescent who does not live with their parent and irregular menstrual cycle were significantly associated with dysmenorrhea. Furthermore, the consequence of untreated dysmenorrhea includes but not limited to social withdrawal, school absenteeism, having poor concentration, a decrease in academic performance, and restriction in daily activities. Adolescents with dysmenorrhea also had a negative attitude consulting a physician, highlighting its importance as a public health issue.” |

| Ahmed and Piro 2012 [59] | Iraq | 185 | NR | NR | 13 ± 1.4 | 1. Mild: 22 2. Moderate: 146 3. Severe: 17 |

1. 3-5 days: 86 2. 6-8 days: 99 |

NR | 1. Illiterate: 73 2. Primary school: 65 3. Intermediate school: 26 4. Secondary school: 6 5. Institute and above: 15 |

“There were significant association between age at menarche, amount of blood flow, taking medication during menstruation and menstrual discomforts (abdominal pain, back pain, nausea and vomiting, anxiety) with school performance. Menstruation characteristics and associated physical and psychological discomforts affect on school performance.” |

| Ahmed et al. 2024 [28] | India | 600 | 13.68 | 1.29 | 13.29 ± 0.96 | NR | 1. Menstruation 3–5 days: 480 (80%) 2. Menstruation >5 days (menorrhagia): 66 (11%) 3. Menstruation <3 days (hypomenorrhea): 54 (9%) |

NR | NR | “In our study, we observed that over two-thirds of the study participants were engaged in good menstrual hygiene practices, while ~40% of them reported menstrual-related school absenteeism. Our study also found evidence that the age of the school girls was associated with their menstrual hygiene management practices. We recommend further research on the impact of menstruation and its management on the academic performance of adolescent school girls. Efforts are also required to develop the capacity of teachers to teach menstrual hygiene education.” |

| Alam et al. 2017 [31] | Bangladesh | 2332 | 14.2 | 0.8665 | 11.9 ± 0.9 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“Risk factors for school absence included girl’s attitude, misconceptions about menstruation, insufficient and inadequate facilities at school, and family restriction. Enabling girls to manage menstruation at school by providing knowledge and management methods prior to menarche, privacy and a positive social environment around menstrual issues has the potential to benefit students by reducing school absence.” |

| Alenur et al. 2024 [32] | India | 231 | 14.35 | 0.746 | 12.9 ± 1.17 | NR | NR | NR | 1. Literates: 164 (100%) 2. Illiterate: 67 (100%) |

“Among the study subjects, most of the school absenteeism was found among the girls who were using pads with a new cloth as menstrual absorbent, compared to those who were using the sanitary pad as a menstrual absorbent. Even though they were following good hygienic menstrual practices, we found school absenteeism was present during menstruation, which may affect their academic performance. To continue good practices, regular reinforcement of knowledge regarding menstrual hygiene by teachers and peer education among girls must be encouraged in schools. To decrease school absenteeism, girls must be educated and encouraged to seek medical advice for dysmenorrhea.” |

| Al-Kindi et al. 2011 [29] | Oman | 404 | 17.5 | 0.98 | 13 ± 1.31 | NR | 1. 2–7 days: 354 (88%) 2. 8–14 days: 50 (12%) |

1. Yes: 338 (84%) 2. No: 66 (16%) |

NR | “Dysmenorrhoea is a prevalent and yet undertreated menstrual disorder among Omani adolescent schoolgirls. The pain suffered can be severe and disabling. Doctors should therefore be prepared to discuss this more freely with schoolgirls. In addition, there is a need for education regarding dysmenorrhoea and treatment options to minimise the impact on school, sports, social and daily activities. “ |

| Al-Matouq et al. 2019 [30] | Kuwait | 763 | 17.4 | 0.7 | 12.1 ± 1.3 | 1. Mild: 119 (18.2%) 2. Moderate: 333 (51.0%) 3. Severe: 201 (30.8%) |

1. ≤3: 31 (4.1%) 2. 4–5: 268 (35.1%) 3. 6–8: 428 (56.1%) 4. >8: 36 (4.7%) |

NR | 1. Intermediate/below: 132 (17.3%) 2. Secondary (high school): 196 (25.7%) 3. Diploma: 76 (10.0%) 4. University and above: 359 (47.0%) |

“Dysmenorrhea seems to be highly prevalent among female high-school students in Kuwait, resembling that of high-income countries. Because of the scale of the problem, utilizing school nurses to reassure and manage students with primary dysmenorrhea and referring suspected cases of secondary dysmenorrhea is recommended.” |

| Arafa et al. 2022 [33] | Egypt | 930 | 15.5 | 0.8 | 13.2 ± 1.2 | NR | 5.02±1.30 days | NR | 1. Illiterate: 399 (42.9%) 2. Literate: 531 (57.1%) |

“In conclusion, menstrual disorders are widely-reported among schoolgirls in South Egypt and it seems that these disorders adversely affect school attendance. Future research should focus on the possible impacts of school counseling on improving school attendance.” |

| Armour et al. 2020 [34] | Australia | 4202 | 17.0038 | 0.4147 | 12.3 ± 1.4 | 6.2 ± 2 | NR | NR | NR |

“Dysmenorrhea was reported by 92% of respondents. Dysmenorrhea was moderate (median 6.0 on a 0-10 numeric rating scale) and pain severity stayed relatively constant with age. Noncyclical pelvic pain at least once a month was reported by 55%. Both absenteeism and presenteeism related to menstruation were common. Just under half of women reported missing at least one class/lecture in the previous three menstrual cycles. The majority of young women at school (77%) and in tertiary education (70%) reported problems with classroom concentration during menstruation. Higher menstrual pain scores were strongly correlated with increased absenteeism and reduced classroom performance at both school and in tertiary education. Despite the negative impact on academic performance the majority of young women at school (60%) or tertiary education (83%) would not speak to teaching staff about menstruation.” |

| Asumah et al. 2023 [17] | Ghana | 338 | 15 | 2.19 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1. No formal education: 190 (56.2%) 2. Basic education: 92 (27.2%) 3. Secondary education: 37 (10.9%) 4. Tertiary: 19 (5.6%) |

“Menstruation related school absenteeism is considered high and could affect girls’ educational attainment. School absenteeism due to menstruation, particularly in public schools, warrants attention by the Ghana Education Service.” |

| Banikarim et al. 2000 [35] | USA | 706 | 16 | 1.4 | 12 ± 1.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Dysmenorrhea is highly prevalent among Hispanic adolescents and is related to school absenteeism and limitations on social, academic, and sports activities. Given that most adolescents do not seek medical advice for dysmenorrhea, healthcare providers should screen routinely for dysmenorrhea and offer treatment. As dysmenorrhea reportedly affects school performance and attendance, school administrators may have a vested interest in providing health education on this topic to their students. |

| Boosey et al. 2014 [36] | Uganda | 140 | 14.45 | 0.908 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“It is common for girls who attend government-run primary schools in the Rukungiri district to miss school or struggle in lessons during menstruation because they do not have access to the resources, facilities, or information they need to manage for effective MHM. This is likely to have detrimental effects on their education and future prospects. A large-scale study is needed to explore the extent of this issue.” |

| Cameron et al. 2024 [37] | Australia | 1835 | 16.5 | 0.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“A large proportion of adolescent girls in Australia experience period pain that affects their engagement in regular activities, including school attendance. Recognising adolescent period pain is important not only for enhancing their immediate quality of life with appropriate support and interventions, but also as part of early screening for chronic health conditions such as endometriosis.” |

| Chongpensuklert et al. 2008 [38] | Thailand | 575 | 16.8737 | 1.0682 | 12.577 ± 1.124 | 1. Mild: 58 2. Moderate: 304 3. Severe: 126 |

1. <7: 441 2. >7: 106 |

NR | NR |

“There is a high prevalence of dysmenorrhea among Thai secondary school students. The condition has a negative impact on educational activities. Most sufferers used acetaminophen to treat their symptoms.” |

| Davis et al. 2018 [39] | Indonesia | 1159 | 15 | 1.07 | 12.4 ± 4.34 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“High prevalence of poor MHM and considerable school absenteeism due to menstruation among Indonesian girls highlight the need for improved interventions that reach girls at a young age and address knowledge, shame and secrecy, acceptability of WASH infrastructure and menstrual pain management.” |

| Dayalan et al. 2017 [40] | India | 340 | 14.77 | 1.46 | 13 ± 1.489 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“Menstrual disorders form a major source of comorbidity in our study group. About 1 in 10 girls attain menarche at an early age less than 12 years and more than half of the girls had menstrual disturbances. But, a very few children seeked medical help for the same, which led to diagnosis of treatable gynecological diseases.” |

| Defert et al. 2024 [41] | France | 257 | 11.1 ± 0.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“The duration of the menstrual cycle was similar between the various socioeconomic groups, but symptoms and ways of coping were significantly different. Dysmenorrhea is definitely an issue that has to be raised with teenagers as soon as menarche occurs or even before that. Easy access to skilled health practitioners should be widespread.” |

||

| Edet et al. 2022 [42] | Nigeria | 673 | 14.4 | 1.8 | 12.2 ± 1.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“findings have shown that school absenteeism during menstruation is a serious problem among respondents capable of adversely affecting their academic performance. Access to sanitary towels and WASH facilities should be provided in schools to create an enabling environment to motivate school attendance by the adolescent girls.” |

| Esen et al. 2016 [43] | Turkey | 824 | 16.2 | 0.8829 | 12.7 ± 1.3 | 1. Severe: 28.8% (245/850) 2. Moderate: 43.3% (368/850) 3. Mild or no pain: 27.9% (237/850) |

1. Irregular periods: 3.2 ± 1.6 days 2. Regular periods: 3.5 ± 1.5 days |

NR | NR | “Dysmenorrhea was found to be common in adolescent Turkish girls and to affect daily life in approximately half of the girls.” |

| Femi-Agboola et al. 2017 [44] | Nigeria | 460 | 15.2 | 1.3 | 9 - 16 | 1. Mild: 126 2. Moderate: 147 3. Severe: 63 |

1. 3 days: 137 2. >3 days: 323 |

NR | NR |

“Prevalence of dysmenorrhea was high and severe dysmenorrhea played a role in school absenteeism. Health education should be provided to address the dangers of self-medication while drugs for pain relief should be available in schools.” |

| Gumanga and Kwame-Aryee 2022 | Ghana | 456 | 16 | 0.93 | 12.5 ± 1.28 | 1. Mild: n = 81 2. Moderate: n = 166 3. Severe: n = 84 |

NR | NR | NR |

“This study shows that dysmenorrhoea is common among girls of this Senior Secondary School in Accra, Ghana. The correct approach to management of adolescent girls with dysmenorrhoea can reduce the adverse impact of severe dysmenorrhoea on academic activities in the form of class absenteeism.” |

| Habtegiorgis et al. 2021 [46] | Ethiopia | 546 | 15.7 | 0.9 | 13.7 ± 0.92 | NR | 1. Less than 2 days: 109 (20.3%) 2. 3 to 7 days: 399 (74.5%) 3. More than 7 days: 28 (5.2%) |

NR | 1. Illiterate: 74 (13.8%) 2. Read and write: 99 (18.5%) 3. Primary: 106 (19.8%) 4. Secondary: 139 (25.9%) 5. College or above: 118 (22.0%) |

“We found that more than half of high school girls had good menstrual hygiene practices. Factors significantly associated with good menstrual hygiene practices include high school girls age 16–18 years, girls grade level 10, maternal education being completed primary, secondary, and college level, having regular menses, good knowledge regarding menstruation, discussing menstrual hygiene with friends and obtaining money for pads from the family. Therefore, educating of high school student mothers about MHP should be a priority intervention area to eliminate the problem of menstrual hygiene among daughters.” |

| Hasan et al. 2021 [47] | Bangladesh | 442 | 16.8 | 1.507 | 13 | NR | NR | NR | 1. Illiterate: 75 (16.9%) 2. Primary: 128 (28.9%) 3. Secondary or above: 239 (54.2%) |

“The study findings may help governmental and non-governmental organizations design interventions to improve knowledge on the menstrual cycle and so reduce school absenteeism during menstrual periods.” |

| Hirai et al. 2024 [48] | Zimbabwe | 1393 | 14.6 | 13.01 | NR | NR | NR | NR | “Students’ age, challenges with concentration, physical sickness, and pain were significantly associated with school absenteeism in this context. Presence of a reliable school water source and availability of adequate handwashing resources at sanitation facilities were protective factors. The evidence-based MHH programming can be further advocated and scaled up to promote students’ good health and wellbeing, maximize their educational opportunities, and develop their fullest potential in life.” | |

| Hoppenbrouwers et al. 2016 [49] | Belgium | 792 | 12.8 | 0.3 | 11.7 ± 0.62 | NR | 1. 1–2 days: n = 12/346 (3.5%) 2. 3–4 days: n = 104/346 (30.0%) 3. 5–6 days: n = 174/346 (50.3%) 4. More than 6 days: n = 56/346 (16.2%) |

NR | NR | “Early menstrual complaints are common in young adolescent girls and the likelihood of pain increased significantly with lower menarcheal age.” |

| Hounkpatin and Aaa 2016 [50] | Benin | 425 | 13.04 | 1.3 | 13.04 ± 1.3 | 1. Mild or light: 33.3% 2. Moderate: 37.8% 3. Severe: 28.8% |

1. <5 days: 374 2. 5+ days: 51 |

NR | NR | “Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in schools is high in Parakou. This high prevalence shows that it is a critical health issue in schools which requires a particular attention, for it is still under-treated due to lack of information. It is therefore urgent to early integrate into school curricula the issues related to reproductive health in order to prepare girls for menstruation. Another measure shall consist in providing them information on treatment options in case of dysmenorrhea.” |

| Ikpeama et al. 2022 [51] | Nigeria | 326 | 15.51 | 1.24 | 12.4 ± 1.2 | 1. Mild: 36 (14.8%) 2. Moderate: 112 (45.9%) 3. Severe: 96 (39.3%) |

3.3408 ± 0.8576 | NR | NR | “The prevalence of dysmenorrhea was high among secondary school girls in Enugu, Nigeria. It was associated with the length of menstrual cycle and duration of flow. There was no association between degree of dymenorrhean and school absenteeism.” |

| Inthaphatha et al. 2021 [52] | Lao | 1366 | 15.8 | (13-19) | 12.9 | NR | 1- 1–2 days: 8 (0.6%) 2- 3–7 days:1330 (97.4%) 3- ≥ 8 days: 28 (2.0%) |

NR | 1- No Education: 166 (12.2%) 2- Primary school: 365 (26.7%) 3- Lower secondary school: 269 (19.7%) 4- Upper secondary school: 312 (22.8%) 5- Diploma or higher: 254 (18.6%) |

“31.8% of the girls reported missing school due to menstruation. Factors associated with school absence included age ≥16 years, higher income, menstrual anxiety, dysmenorrhea, and disposing used pads in places other than school waste bins. The study suggests improving school toilet facilities and starting menstrual education at elementary schools.” |

| Jahan et al. 2024 [53] | Bangladesh | 2,332 (2014) | 12.5 | NR | 11.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“The study found a significant decrease in menstruation-related absenteeism from 2014 to 2018, highlighting the impact of improved menstrual hygiene management (MHM) facilities and education.” |

| 2,800 (2018) | 13.2 | NR | 11.7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Tegegne and Sisay 2014 [73] | Ethiopia | 574 | 14.96 | 1.33 | 13.98 ± 1.17 | NR | NR | 1. Yes: 257 (43.3%) 2. No: 317 (56.7%) |

NR |

“The lack of sanitary napkins and inadequate school facilities significantly contribute to school absenteeism and dropout rates among girls. Improving menstrual hygiene support and infrastructure is crucial for enhancing girls' educational opportunities.” |

| Krishnaiah et al. 2023 [15] | India | 400 | 14.45 | 1.71 | 12.27 ± 2.46 | NR | NR | NR | 1- Illiterate/Non-formal education: 46 (11.5%) 2- Primary School: 26 (6.5%) 3- Middle School: 49 (12.25%) 4- High School: 117 (29.25%) |

“High menstruation-related school absenteeism (30.25%) driven by lack of facilities,, and social restrictions. Interventions needed: better menstrual hygiene education and improved school infrastructure.” |

| Kuhlmann et al. 2020 [63] | USA | 58 | 15.21 | 1.23 | 11.8 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“Students face significant challenges accessing menstrual hygiene products, often relying on school resources to obtain them. Ninth graders, in particular, experience more absences due to inadequate product supply, highlighting the need for targeted support in junior high and lower grades. Schools should prioritize providing menstrual products and related support, especially in settings where basic needs are unmet. Districts must expand efforts beyond simply placing products in schools to comprehensively address menstruation-related absences.” |

| Kuhlmann et al. 2024 [64] | USA | 119 | 15.78 | 1.28 | 12.11 ± 1.35 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“Menstrual product insecurity is a major issue for U.S. high school students, particularly in low-income areas. Many students struggle to access these products, leading to school absences and disciplinary problems. Schools can help by providing free menstrual products and education on menstrual hygiene. The study suggests states should pass laws requiring schools to supply these products and fund related initiatives. It also stresses the need for comprehensive menstrual hygiene education to improve student knowledge and reduce absences.” |

| Kumbeni et al. 2021 [54] | Ghana | 705 | NR | 12–19 | 12.27 ± 2.46 | NR | NR | NR | 1- No formal education: 527 (74.8%) 2- Primary education: 153 (21.8%) 3- Secondary or higher education: 25 (3.4%) |

“High menstruation-related school absenteeism (27.5%) linked to older age, cloth use, and cultural restrictions. Interventions needed: better sanitary pad access, removing cultural barriers, and boosting parental income.” |

| Lghoul et al. 2020 [55] | Morocco | 364 | 16.65 | 1.83 | 12.89 ± 1.34 | 1- Mild: 84 (10.2%) 2- Moderate: 115 (31.7%) 3- Severe: 165 (58.1%) |

1- <4 days: 27 (7.4%) 2- 4–7 days: 234 (64.3%) 3- >7 days: 103 (28.3%) |

NR | NR |

“The study found that a high percentage (78%) of schoolgirls in Marrakesh experience dysmenorrhea, highlighting a significant link between gynecological age and the condition. The notable rate of absenteeism underscores dysmenorrhea as a public health concern for adolescent girls. Since it impacts not only the girls but also their families and social lives, the study calls for improved management through educational programs.” |

| Marques et al. 2022 [56] | Portugal | 808 | 15.5 | 1.6 | 12.4 ± 1.3 | NR | 1- ≤6 days: 703 (83%) 2- 6 days: 145 (17.2%) |

NR | NR |

“The study found menstrual disorders are common and may link to early menarche, but not BMI. It stresses the need for self-monitoring to detect issues early and support health and well-being.” |

| Method et al. 2024 [57] | Tanzania | 400 | 10–19 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1- Didn’t know: 18 (4.5%) 2- No formal education: 47 (11.75%) 3- Primary-level education: 232 (58%) 4- Secondary education: 79 (19.75%) 5- College Education: 18 (4.5%) 6- University education: 6 (1.5%) |

“This study calls for promoting MHM-friendly practices in schools to create a supportive and conducive learning environment for adolescent girls. Ongoing infrastructure improvements such as the construction of classrooms and toilets in schools should include the construction of proper changing places to reduce the number of adolescent girls who miss school due to menstruation.” | |

| Miiro et al. 2018 [78] | Uganda | 352 | 15.7 | 0.5 | 13.2 ± 0.1 | NR | 3.7 ± 0.1 | NR | Primary or below education: 99 (28.2%) |

“Menstruation was strongly associated with school attendance in this peri-urban setting, and that there is an unmet need to investigate interventions for girls, teachers and parents which address both the knowledge and psychosocial aspects of menstruation (self-confidence, attitudes) and the physical aspects (management of, use of appropriate materials to eliminate leakage of menstrual blood, improved WASH facilities).” |

| Mohammed et al. 2020 [13] | Ghana | 250 | NR | 10–19 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“Half of surveyed girls maintained good menstrual hygiene, but 40% missed school due to menstruation. Factors influencing hygiene included age, father's job, and product allowance. The study calls for more research on menstruation's impact on academic performance and large-scale studies on the broader reproductive health effects of poor hygiene beyond attendance and grades.” |

| Ortiz et al. 2009 [58] | Mexico | 1152 | 18.2 | 1.3 | 12.2 ± 1.3 | Mild: 183 (32.9%) Moderate: 277 (49.7%) Severe: 97 (17.4%) |

1–5 days: 969 (84.1%) >5 days: 183 (15.9%) |

NR | NR |

“Dysmenorrhea prevalence was high (48.4%), causing school absences (24% of affected students). Self-medication was common (60.9%), and formal medical care was underutilized (28% consulted a physician). The study highlights the need for health education to address unnecessary suffering and educational disruptions.” |

| Pitangui et al. 2013 [60] | Brazil | 174 | 13.65 | (12-17) | 13.71 years Range: 9–15 years |

1-Mild: 21 (10.24%) 2-Moderate: 77 (37.80%) 3-Severe: 107 (51.97%) |

1- ≤3 days: 1 (0.5%) 2- 3–7 days: 186 (90%) 3- >7 days: 18 (8.6%) |

NR | NR |

“Among the menstrual disturbances observed, dysmenorrhea stood out due to its high prevalence among adolescents and its negative effect on adolescents’ activities of daily living. Early diagnosis and knowledge about menstrual disturbances are essential because, in addition to reiterating the importance of implementing health education actions, they also help to choose appropriate treatments, thus minimizing the negative effects of these disturbances on the lives of adolescents.” |

| Rupe et al. 2022 [61] | Haiti | 200 | 19.7 | 0.9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“In rural Haiti, three-quarters of adolescent and young adult (AYA) females reported menses-related school absenteeism, and two-thirds had unmet MH needs. Many lacked a safe environment to change menstrual materials, with over half worrying about harm while changing materials at home and school. The study highlights the critical need for improved menstrual health resources and safe environments, particularly in post-disaster settings, to ensure school attendance and reduce psychosocial and health risks.” |

| Santina et al. 2012 [62] | Lebanon | 389 | 15.8 | 1.4 | 12.5 ± 1 | NR | 1- ≤6 days: 174 (44.7%) 2- ≥7 days: 215 (55.3%) |

NR | 1- Primary education: 35 (9.0%) 2- Elementary school: 103 (26.5%) 3- Secondary education: 120 (30.8%) 4- University: 131 (33.6%) |

“Menstrual and other symptoms are prevalent among Lebanese teenagers, leading to school absences and few seeking medical help. Health professionals should raise community awareness and update school curricula to educate girls on this health issue. Girls with moderate to severe and multiple menstrual symptoms, along with school absence and disrupted activities, need effective management or referral to reduce menstrual morbidity.” |

| Shah et al. 2022 [65] | Gambia | 561 | 15.8 | 1.4 | 14 ± 1.67 | 1- No: 99 (17.65%) 2- Mild: 283 (50.45%) 3- Extreme: 179 (31.91%) |

1- ≤6 days: 251 (44.7%) 2- ≥7 days: 310 (55.3%) |

NR | 1- No formal education: 175 (31%) 2- Arabic education: 257 (45.81%) 3- Primary education: 41 (7.31%) 4- Secondary education: 27 (4.81%) 5- Unknown: 61 (10.87%) |

“Menstruation severely impacts school attendance for rural Gambian girls due to, poor WASH, limited product access, infections, and cultural stigma. High absenteeism needs urgent action. Recommendations include community education, involving males, training mothers/teachers, curriculum integration, management, and WASH improvements. Addressing product access and knowledge is vital. A comprehensive intervention is needed for policy evidence and gender equity in education.” |

| Sivakami et al. 2019 [66] | India | 2564 | 14.1 | 1.1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

“Menstrual hygiene education, accessible sanitary products, relief, and adequate sanitary facilities at school would improve the schooling-experience of adolescent girls in India.” |

| Söderman et al. 2019 [67] | Sweden | 1580 | 16.2 | (16-20) | 12.4 | 1- Mild: 387 (25%) 2- Moderate: 619 (39%) 3- Severe: 574 (36%) |

NR | NR | NR | “The findings demonstrate that menstrual is prevalent among teenagers in Stockholm. The results indicate that many women are disabled in their daily life and that only a small number of women seek medical attention, although possible selection bias might have affected the results. Information and education are needed to optimize the use of existing treatment options and more awareness is needed to reduce normalization of disabling dysmenorrhea.” |

| Stoilova et al. 2022 [16] | Tanzania | 523 | 15.2 | 1.4 | 14.2 ± 1.1 | Severe: 188 (36%) | NR | NR | NR | “The study links menstrual hygiene challenges (knowledge gaps, stigma,, poor facilities) to girls' education issues like absenteeism and poor focus. It recommends relief, tech tools, infrastructure upgrades, and community programs to address stigma. Future research should assess long-term effects and holistic solutions.” |

| Swe et al. 2022 [68] | Myanmar | 421 | 14 | 1.46 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | “Adolescent girls in Magway encounter substantial menstrual health challenges, worsened by limited awareness, societal stigma, poor WASH infrastructure, and unacknowledged menopausal issues. These factors contribute to school absenteeism and decreased engagement, adversely affecting their education and well-being. Initiatives should focus on holistic education, dispelling myths, enhancing facilities, and supplying menstrual products/ relief to overcome these obstacles.” |

| Tadakawa et al. 2016 [69] | Japan | 901 | 17 | 1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | “One in nine Japanese female high school students were absent from school due to premenstrual symptoms. Physical premenstrual symptoms and lifestyle factors such as a preference for salty food and lack of regular exercise were identified as risk factors for school absenteeism.” |

| Tangchai and Titapant 2004 [70] | Thailand | 789 | 19.8 | 0.8 | 13 ± 1.2 | 1-Mild: 375 (47.7%) 2-Moderate: 374 (47.6%) 3-Severe: 37 (4.7%) |

NR | NR | NR | “Dysmenorrhea is a significant public health problem among Thai adolescents, affecting academic activities and social life. Most of the subjects know that Paracetamol is the drug that helps to relieve their symptoms.” |

| Tanton et al. 2021 [71] | Uganda | 252 | 15.4 | 1.31 | 13 ± 1.49 | NR | 4.1 ± 1.1 | NR | NR | “Menstrual anxiety is prevalent among Ugandan schoolgirls, and menstrual is associated with missing school. Interventions should address socio-cultural aspects and provide education on management to support school attendance.” |

| Taş et al. 2021 [72] | Turkey | 928 | 16.37 | 1.17 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | “Primary dysmenorrhea significantly impacts the social and school lives of high school students, leading to absenteeism and affecting daily activities.” |

| Ubochi et al. 2023 [74] | Nigeria | 20 | 14.5 | (8-20) | 11 | NR | NR | NR | 1- No Education: 2 (10%) 2- Primary Education: 6 (30%) 3- Secondary Education: 20 (50%) 4- Tertiary Education: 2 (10%) |

“The study proposes the menstruation behaviour influencer model to address menstrual shame, stigma, and absenteeism through home-school collaboration. Key recommendations include providing menstrual education, water/sanitation facilities, and girl-friendly support systems in schools.” |

| Vashisht et al. 2018 [75] | India | 600 | 13 | (12-18) | 13 | NR | NR | NR | 1- Literate Mothers: 454 (75.7%) 2- Illiterate Mothers: 146 (24.3%) |

“The study highlights that nearly 40% of girls miss school during menstruation due to, lack of facilities, and social stigma. Improving menstrual hygiene management (MHM) facilities and education is crucial to reduce absenteeism and improve academic performance. Mothers should be counseled to discuss menstruation openly with their daughters, and schools should provide adequate water, sanitation, and hygiene facilities.” |

| Yaliwal et al. 2020 [76] | India | 928 | (10-19) | 13.5 | 1- Less than 4 days: 414 (40.7%) 2- 5-6 days: 473 (46.6%) 3- More than 7 days: 91 (9%) |

NR | Primary education or were lesser educated: 505 (49.7%) | “Menstrual morbidities, poor menstrual hygiene practices, and cultural restrictions significantly impact school attendance and performance. Improving school WASH facilities and awareness programs is critical.” | ||

| Yucel et al. 2018 [77] | Turkey | 1274 | 13.5 | (9-18) | 12.74 ± 1.03 | 1- Mild: 201 (18.6%) 2- Moderate: 580 (53.7%) 3- Severe: 299 (27.7%) |

1- 4–6 days: 802 (63.2%) 2- >7 days: 483 (35.4%) |

NR | NR | “Dysmenorrhea is common in adolescent girls, impacting their life, school, and attendance. Few seek help due to lack of knowledge and societal attitudes. Schools, parents, and health centers must educate girls, with a focus on mothers. Improved information and accessible healthcare can enhance girls' well-being, academic performance, and future reproductive health.” |

3.4. Results of Syntheses

3.4.1. Prevalence of Absenteeism

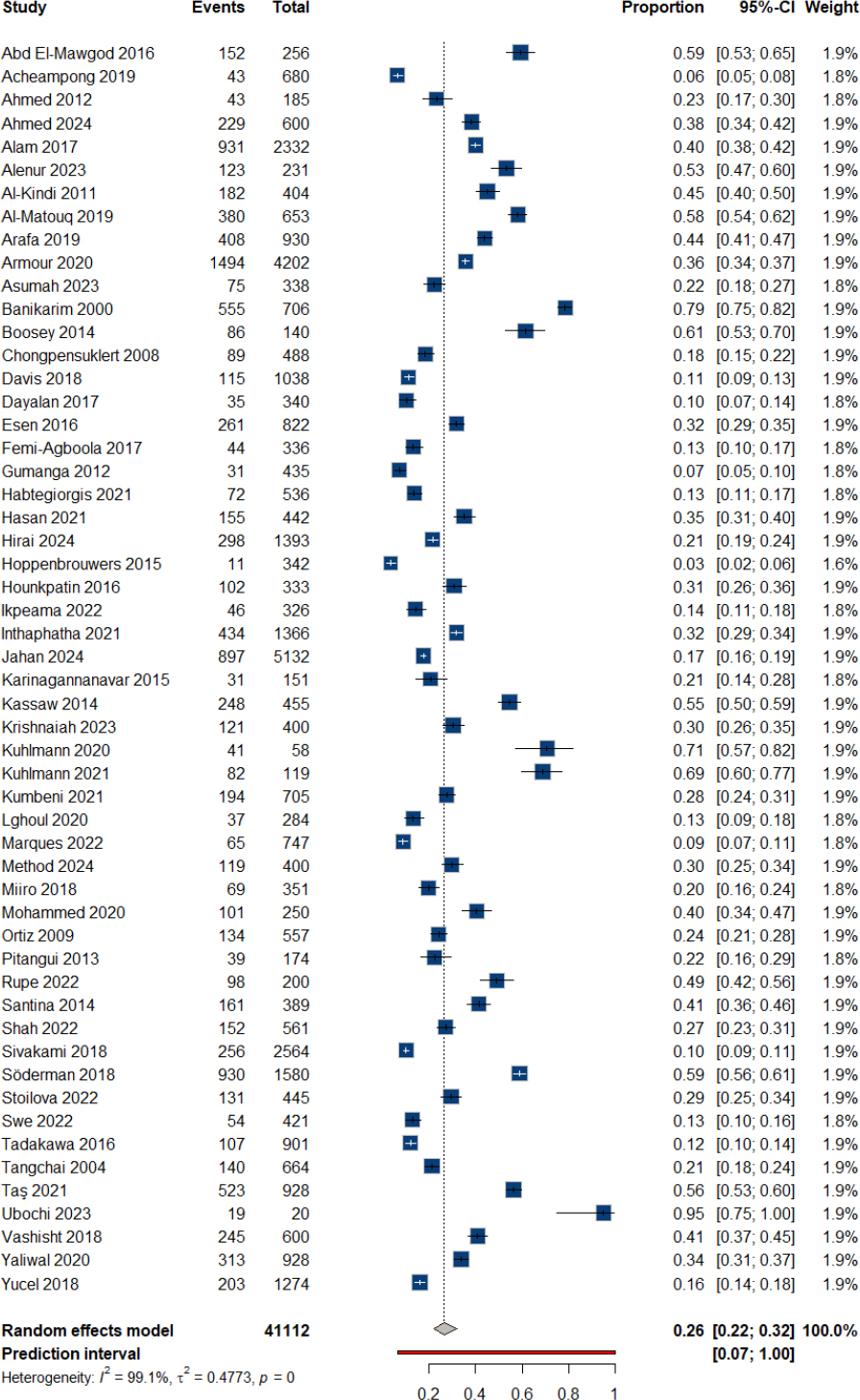

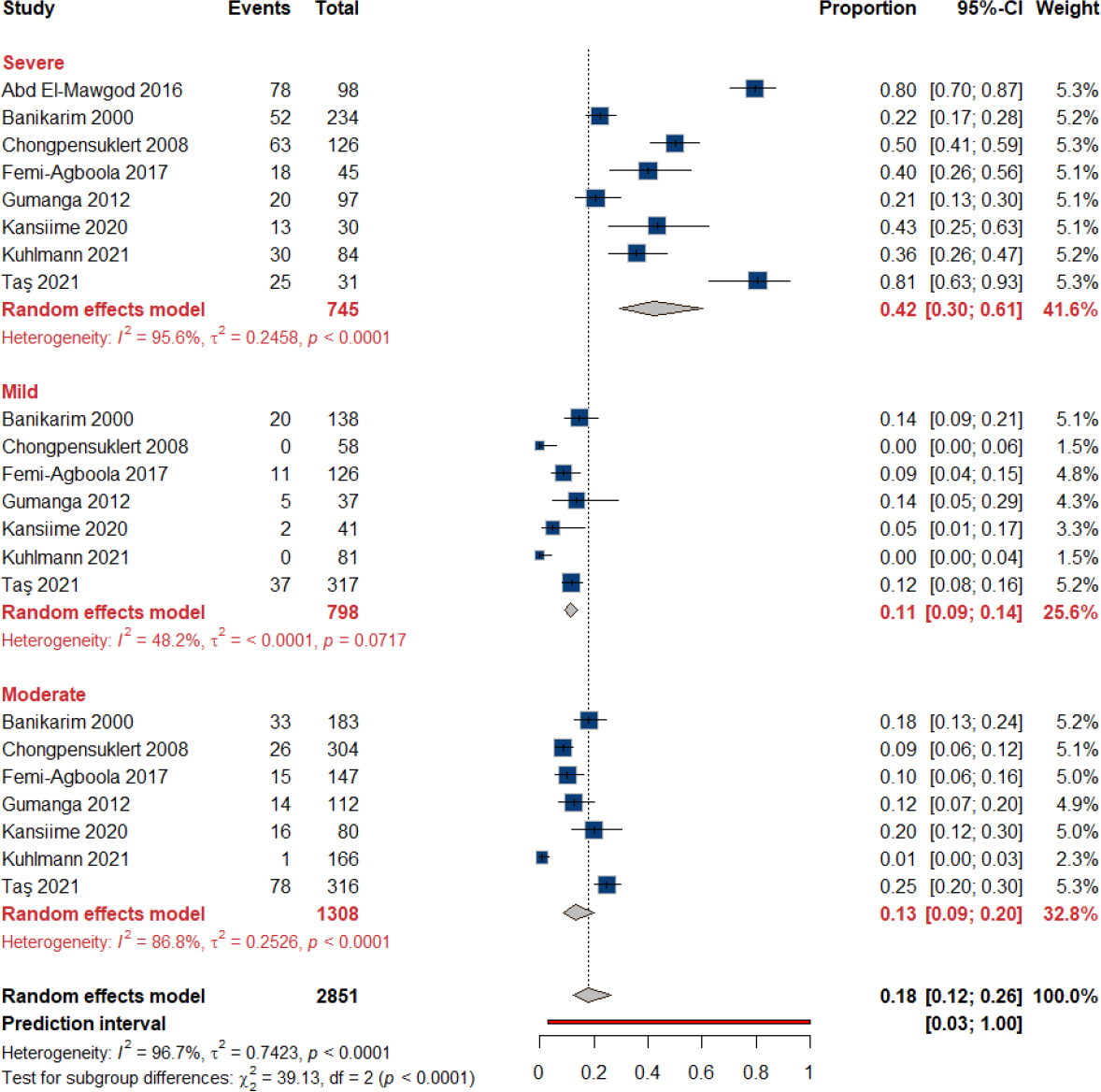

Fifty-four studies reported the prevalence of absenteeism during menstruation with a total of 41,112 participants. We found that the overall prevalence of absenteeism during menstruation among schoolgirls was 26.5% (95% CI: 21.98% to 31.89%), with significant heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 99.1%, tau2 = 0.4773), Fig. (2). When examining the prevalence of absenteeism in different pain subgroups, the proportion of absenteeism was highest in the severe pain subgroup (42.32%, 95% CI: 29.59% to 60.51%), followed by the moderate pain subgroup (13.14%, 95% CI: 8.60% to 20.08%) and the mild pain subgroup (11.37%, 95% CI: 9.21% to 14.05%). The test for subgroup differences was statistically significant (p < 0.0001), Fig. (3). Pairwise analysis comparing absenteeism by pain severity groups showed statistically significant differences between severe pain and both mild and moderate pain groups, while no significant difference was observed between mild and moderate pain groups. The odds ratio for severe vs. moderate pain was 4.86 (95% CI: 3.25 to 7.28, p < 0.0001), and for severe vs. mild pain it was 5.76 (95% CI: 3.89 to 8.53, p < 0.0001). No significant difference was observed between moderate vs. mild pain (OR = 1.19, 95% CI: 0.83 to 1.71, p = 0.342). The data for this pairwise comparison are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Forest plot of prevalence of absenteeism.

Forest plot of the effect of pain on absenteeism.

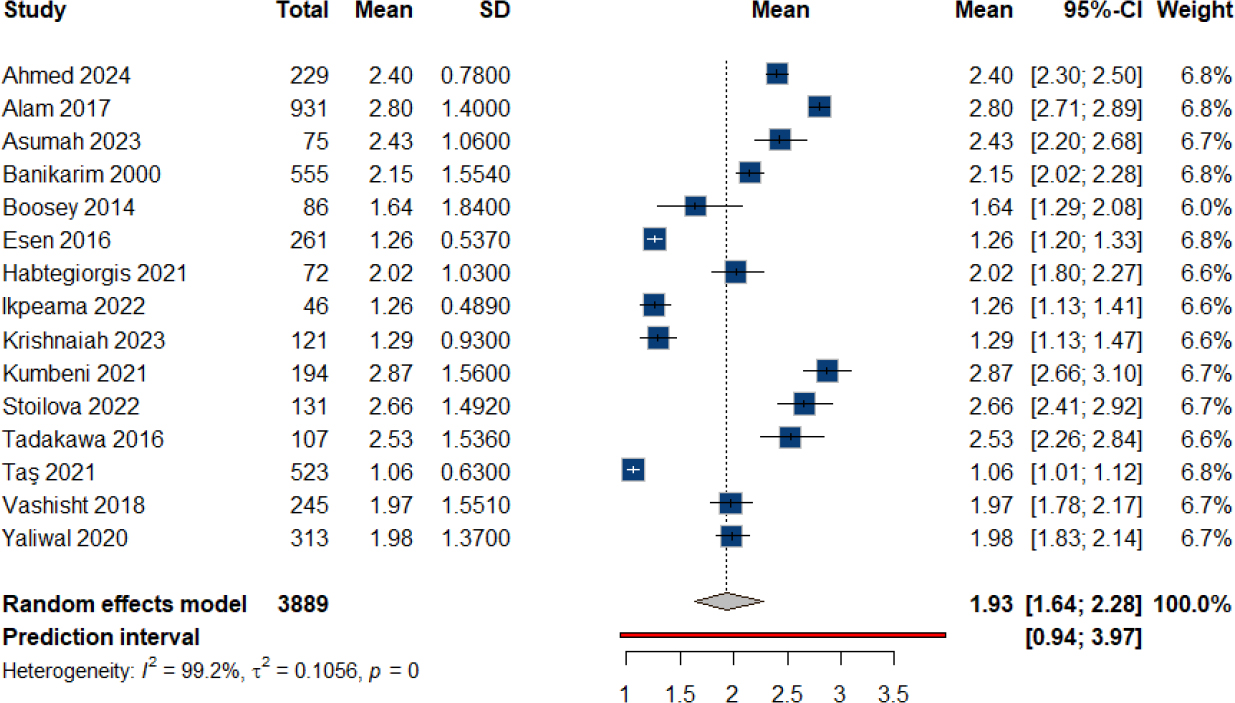

3.4.2. Duration of Absenteeism

The duration of absenteeism during periods was reported in 15 studies with a total of 3,889 observations. We estimated that the mean duration of absenteeism during menstruation among schoolgirls was 1.93 days (95% CI: 1.63 to 2.28), Fig. (4).

3.4.3. Maternal Illiteracy

We analyzed the association between maternal illiteracy and absenteeism among schoolgirls, based on data from 6 studies with a total of 3,103 observations (1,300 in the experimental group and 1,803 in the control group). The number of events (absences) was 1,072. The random effects model resulted in an OR of 1.7143 (95% CI: 0.9130 to 3.2190), with a p-value of 0.0936, which did not reach statistical significance, Fig. (5).

Forest plot of the duration of absenteeism.

Forest plot of the effect of maternal illiteracy on absenteeism.

4. DISCUSSION

Menstruation is a normal process involving multiple biological and cultural aspects. Painful menstruation affects 50% to 90% of menstruating women [2] and significantly impacts daily activities and quality of life. Such pain leads to degraded academic performance and absenteeism [21]. The condition, driven by lifestyle and psychological stress, is inadequately managed due to stigma and lack of awareness [4-10]. In addition, inadequate menstrual hygiene management (MHM), cultural taboos, and limited access to sanitary products further exacerbate absenteeism in low-resource settings [13-15]. Higher maternal education and family support have been shown to improve MHM practices and reduce absenteeism [14, 19, 20]. This review aims to assimilate all existing evidence regarding absenteeism in schoolgirls to determine the overall prevalence, effect of pain severity, and maternal illiteracy.

Our results showed that the overall prevalence of absenteeism during menstruation among schoolgirls was 26.5% (95% CI: 21.98% to 31.89%), with significant heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 99.1%). This estimate is higher than the 15% previously reported by Starr et al., though the authors pooled their results across all age groups up to working age [22]. Absenteeism was highest in the severe pain subgroup (42.32%, 95% CI: 29.59% to 60.51%), followed by moderate (13.14%, 95% CI: 8.60% to 20.08%) and mild pain subgroups (11.37%, 95% CI: 9.21% to 14.05%), with significant differences between severe and mild/moderate pain groups (p < 0.0001). Additionally, the mean duration of absenteeism was 1.93 days (95% CI: 1.63 to 2.28). Although maternal illiteracy was associated with a higher odds ratio for absenteeism (OR = 1.7143, 95% CI: 0.9130 to 3.2190), this relationship did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.0936).

The high heterogeneity in the prevalence is influenced by a multitude of factors such as barriers to proper MHM, stigma, and biological variables. Dysmenorrhea was the strongest contributor to school absenteeism, and it had a prevalence ranging from 59.4% to 89.1% in the included articles [26, 33]. Severe menstrual pain was strongly associated with absenteeism, as evidenced by Yucel (2018), who reported a mean pain score of 7.91 among absentee girls, and Taş (2021), who found that students with dysmenorrhea were 3.61 times more likely to miss school [72, 77]. Tanton (2021) and Marques (2022) further confirmed the impact, where dysmenorrhea was linked to an OR of 3.82 for absenteeism and 65.7% of girls experiencing limitations in daily activities [56, 71]. Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) exacerbated absenteeism due to fear of leakage and physical discomfort [63, 75]. Comorbid symptoms, such as premenstrual syndrome (PMS), and extragenital symptoms like headaches and fatigue further disrupted attendance [33, 67, 69]. Fear of leakage and staining, as well as fatigue, added to absenteeism [13, 38, 42]. These factors collectively impair academic performance, leading to missed exams and reduced classroom concentration [30, 50, 55]. Addressing these issues requires interventions tailored to mitigate the impact of menstrual-related challenges on education.

Cultural stigma and infrastructure deficits significantly drive school absenteeism during menstruation. Cultural taboos and restrictions, such as avoiding religious ceremonies [76] or facing shame [74, 78], disproportionately impact attendance, with girls under 15 being 3.69 times more likely to miss school [17]. Fear of teasing [13, 42] and cultural restrictions also exacerbate absenteeism [26, 54]. Infrastructure disparities, such as inadequate toilets [36, 75] and lack of menstrual products, further compound the issue, with girls lacking disposable pads being 5.37 times more likely to miss school [73]. Poor waste disposal [15] and dysfunctional facilities [66] heighten absenteeism risks. Moreover, rural girls face 59% higher absenteeism odds due to facility gaps [73] and systemic failures, such as inadequate infrastructure [42]. Conversely, improved water access and handwashing stations reduce absenteeism by 32.1% and 55.3%, respectively [48].

While our analysis included studies from diverse geographic regions, explicit geographic-specific analyses were not feasible due to the variability and inconsistent reporting of cultural factors across studies. Recognizing that cultural practices and perceptions related to menstruation vary significantly between regions, future research should explicitly examine geographic and cultural contexts to better understand their specific impacts on school absenteeism.

Socioeconomic and educational barriers mediated menstrual-related school absenteeism. In contrast to the findings from our studies, girls with illiterate mothers (AOR = 5.36) or fathers (AOR = 4.66) faced higher absenteeism risks [47], while those from single-parent households were 2.54 times more likely to miss school [17]. Limited healthcare access exacerbated absenteeism, as only 7% of girls sought medical help for dysmenorrhea [67], and unaddressed pain worsened attendance [26]. Girls unaware of menstruation before menarche were at higher risk (AOR = 2.14) of absenteeism compared to their counterparts [47]. Negative teacher attitudes, such as teasing and joking [74], discourage attendance. Poverty-driven barriers, such as unaffordable menstrual materials, also heighten absenteeism [78].

During this review, we assembled all existing evidence regarding the prevalence of absenteeism during menstruation in schoolgirls. We further analyzed possible associations and compiled biological, cultural, and socioeconomic parameters from the included studies. Nonetheless, many studies did not provide such factors in a consistent format suitable for analysis. Moreover, the lack of access to primary data regarding contributing variables made inference from existing literature impossible. Future studies are advised to take a holistic approach when investigating menstruation-related absenteeism and make their data available for further analysis.

5. LIMITATIONS

This systematic review and meta-analysis have several limitations. Significant heterogeneity across included studies limits the generalizability of our findings. Variability in data collection methods and inconsistent definitions across studies introduce potential biases. Geographic-specific and cultural factors were inadequately represented due to inconsistent reporting, restricting deeper analysis. Moreover, the cross-sectional design of the included studies precludes drawing causal conclusions. Future research should address these limitations by standardizing definitions and methods and exploring detailed geographic and cultural contexts explicitly.

CONCLUSION

Menstruation-related absenteeism significantly disrupts education for schoolgirls, driven predominantly by severe dysmenorrhea, cultural stigma, and inadequate menstrual hygiene infrastructure. Pain severity shows a direct relationship with absenteeism, while systemic barriers, such as lack of sanitary products and socioeconomic disparities, disproportionately affect marginalized groups. Cultural taboos and insufficient health literacy further amplify these challenges, leading to intermingled vulnerabilities. Conversely, maternal education and improved infrastructure demonstrate protective effects. Addressing this issue requires holistic strategies integrating medical, educational, and policy reforms to mitigate both biological and structural inequities. Future research should prioritize standardized, intersectional analyses to inform the decision-making process.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: A.Y.Z.: Study conception and design; M.A.: Data collection; M.A. and R.M.M.H.: Analysis and interpretation of results; A.S., S.S.M. and S.A.A.: Visualisation; D.M.M., W.E.M. and H.A.F.: Writing, reviewing, and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| AOR | = Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| BMI | = Body Mass Index |

| CI | = Confidence Interval |

| HMB | = Heavy Menstrual Bleeding |

| MHM | = Menstrual Hygiene Management |

| NSAIDs | = Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| OR | = Odds Ratio |

| PMS | = Premenstrual Syndrome |

| PRISMA | = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| REML | = Restricted Maximum Likelihood |

| SD | = Standard Deviation |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank all authors for their contributions to this work.