All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Depression and Anxiety among Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: Systematic Review of Literature

Abstract

Introduction

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM) is one of the most prevalent chronic endocrine diseases among adolescents in the world. Studies reported that adolescents with T1DM complain of anxiety and depression. The current study aims to review depression and anxiety among adolescents with T1DM.

Methods

A literature review was conducted using the MEDLINE, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Science Direct Databases, with the following keywords: “Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus,” “Adolescents,” “Depression,” and “Anxiety.” The search included published studies between 2011 and 2024.

Results

Sixteen articles were included in the current review. The findings indicated high levels of anxiety and depression among adolescents with T1DM, which were associated with poor glycemic control and elevated HbA1c levels. Female adolescents with T1DM were associated with a higher level of anxiety and depression than males.

Discussion

This systematic review emphasizes the importance of integrated mental health support in diabetes care for adolescents with T1DM.

Conclusion

Healthcare providers should screen for depression and anxiety, use multidisciplinary approaches, and involve schools and families in fostering a supportive environment.

1. INTRODUCTION

Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM) is increasing globally, particularly in younger populations [1]. It is believed that environmental factors, viral infections, and genetic predispositions may contribute to this rise [2]. In 2022, the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) found that 1.52 million adolescents and children under 20 years old were living with T1DM [3]. In the Middle East and North Africa, there were 201,000 newly diagnosed with T1DM under 20 years [4]. In Jordan, it was documented that there were 1,291 cases of T1DM in individuals under 20 years of age annually [5]. Adolescence is a unique period marked by changes in various aspects, including emotional, physical, mental, and behavioral development [6]. Globally, this period of life is characterized by different mental problems such as depression and anxiety [7]. In addition to the previous changes and adolescent characteristics, pediatric patients who are diagnosed with diabetes complain of different psychological challenges, such as anxiety and depression, that affect their choices in life [8]. Furthermore, a high prevalence of anxiety and depression has been reported among individuals living with T1DM [9].

Newly diagnosed adolescents with T1DM reported more depression symptoms than those who had lived with it for several years [10-12]. For instance, a recent study performed by Nguyen et al., [13], reported that adolescents frequently suffer from anxiety and mood disorders, which are linked to previous disorders. Higher symptom severity was associated with greater diabetic distress. So, it is recommended that clinicians deal with past psychiatric issues and keep an eye out for them.

Similarly, Goncerz et al., [14], found depressive symptoms among female adolescents with T1DM more than males. Another study conducted in Jordan found that the prevalence of depression among adolescents with T1DM was associated with high levels of HbA1c and less frequent glucose monitoring [15-18]. Although Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM) and its physical implications have been the subject of several studies, less is known about the psychological burden, particularly anxiety and depression, experienced by teenagers with T1DM. Current studies frequently concentrate on mental health or diabetes treatment independently, without thoroughly examining how these variables interact. Furthermore, it is challenging to draw consistent conclusions from prior studies due to variations in methodology, sample characteristics, and outcome measures. By thoroughly evaluating and combining data from various studies, this systematic review fills in these gaps. It offers a better understanding of the prevalence, risk factors, and effects of anxiety and depression in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. This study aims to inform more targeted interventions and integrated care methods by highlighting trends and discrepancies in the existing body of literature [8, 19]. Hence, the current study aims to review the mental problems, especially depression and anxiety, among adolescents with T1DM.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Search Strategy

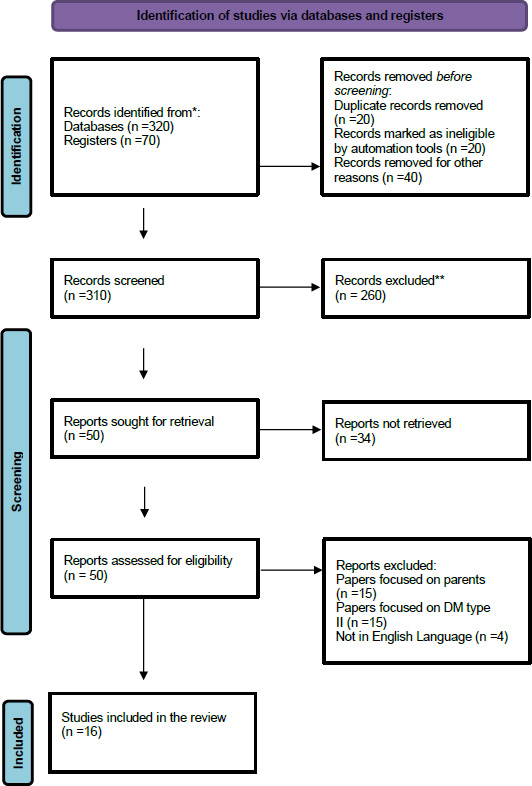

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) workflow (Fig. 1). The search included published studies from the period of 2011 to 2024.

The systematic review was conducted using MEDLINE, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Science Direct Databases using the following keywords: “Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus”, “ Adolescents”, “Depression”, and “Anxiety” (Table 1).

| S.No. | Authors/Refs. | Year of the Study | Participants and Sample Size | Adolescents with T1DM Symptoms | Study Design | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Buchberger et al., [21] | 2016 | The participants were aged between 13.4 to 17.7 years Sample size: N/A |

Depression and anxiety | Systematic review and meta-analysis | This review indicated that there was a high prevalence of depression (30.04%) and anxiety (32%) among patients with T1DM, and that was associated with a negative impact on glycemic control and HbA1c levels. |

| 2 | Jaser et al., [35] | 2017 | The participants were aged between 10-19 years Sample size: 117 |

Depression | Cross-sectional design | This study indicated that poor coping with T1DM among adolescents is associated with depression symptoms and poor quality of life. |

| 3 | Kongkaew et al., [45] | 2014 | Participants with T1DM Sample size: 2,935 juveniles |

Depression | Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies | This review indicated there was a moderate association between depression and adherence or poor glycemic control among adolescents with T1DM. |

| 4 | Watson et al., [22] | 2020 | The participants were aged between 10-18 years Sample size: 77 |

Anxiety and depression | Cross-sectional design | In this study, 77 patients were screened with the Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents over six months. They found that 40% of adolescents with diabetes thought about harming themselves, and one of them experienced current active depression symptoms. 32 patients reported depression symptoms, 20 had both depression and anxiety symptoms, and 11 complained of anxiety only. |

| 5 | Goncerz et al., [14] | 2023 | The participants aged between 15-19 years Sample size: 59 |

Anxiety and depression | A single-centre observational study | A total of 59 participants completed questionnaires (Children’s Depression Inventory 2 and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory). This study indicated that depression symptoms are higher among females than among males. A high level of HbA1c was associated with low function levels. |

| 6 | Adal et al., [23] | 2015 | The participants aged between 11-18 years Sample size:295 |

Anxiety and depression | Cross-sectional study | A total of 295 participants completed the Children’s Depression Inventory and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI I-II) for Children questionnaire. This study indicated the depression rate was 12.9%, and there was a high level of anxiety among adolescents with T1DM. |

| 7 | Singh et al., [46] | 2024 | The participants aged between 12-18 years Sample size:251 |

Anxiety and depression | Cross-sectional study | A total of 251 participants completed the Patient Health sectional study. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder 9 (PHQ9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD7) questionnaire. The results indicated that 46% of participants complained of depression and 40.06% complained of anxiety. |

| 8 | Martinez [32] | 2018 | The participants were adolescents with T1DM Sample size:21 article |

Anxiety and depression | A systematic review | This systematic review scans different types of psychiatric diseases and focuses on depression and anxiety. The results indicated there was a negative correlation between anxiety and depression with adherence among adolescents with T1DM. |

| 9 | Herzer and Hood [33] | 2010 | The participants aged between 13-18 years Sample size: 276 |

Anxiety | Cross-sectional design | The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was used to measure anxiety symptoms. The results indicated that adolescents with a higher level of anxiety were associated with a lower frequency of measuring the blood glucose level and uncontrolled glycemic control. |

| 10 | Reynolds, Altmann and Allen [37] | 2021 | The participants aged between 11-19 years Sample size:81 |

Anxiety | Cross-sectional design and retrospective review | Records were used for the utilization of the GAD-7 screening tool for patients with T1DM during routine follow-up in diabetes units. The results indicated that most adolescents with T1DM feel anxious, and females have higher anxiety levels than males. |

| 11 | Nguyen et al., [13] | 2021 | The participants aged between 12-18 years Sample size:171 |

Anxiety and depression | Longitudinal study | This study indicates that 49 (29%) adolescents with T1DM complain of anxiety during their lifetime and 23 (13%) during the last year. Anxiety disorder is higher than any other mood disorder among adolescents with T1DM. Depression results from anxiety among adolescents with T1DM. |

| 12 | Majidi et al., [28] | 2015 | The participants were pediatric patients with T1DM Sample size: N/A |

Anxiety | Narrative Literature Review | This study found that most of the anxiety among adolescents with T1DM is from fear of needles, hypoglycemia, and using technology-related diabetes as continuous glucose monitoring. |

| 13 | Rechenberg and Koerner [10] | 2019 | The mean age of participants was 13.4 years Sample size:67 |

Anxiety | Cross-sectional design | The participants in this study completed the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (STAIC) to measure anxiety levels. The results indicated a higher rate of anxiety and poor self-management among adolescents with T1DM (r = −0.49, P < .01), and it was also associated with high levels of HbA1c. Adolescents with a lower level of anxiety have better levels of HbA1c. |

| 14 | Martin et al., [47] | 2022 | Adolescent female aged 13 years Sample size:1 |

Depression | Case report | A case report for a female adolescent with T1DM reported that she complained of depression symptoms for 3 months. Since she was diagnosed with T1DM feels loneliness, tiredness, and worse, thinking about the future at night. The clinic reported high glucose levels associated with depression in this case. |

| 15 | Naruboina, Praveen [25] | 2017 | The participants were aged between 11-19 years Sample size: 30 |

Depression | Cross-sectional design | In this study, all participants completed the Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ-9) to measure depression levels. The results of this study indicated that 60% of adolescents with T1DM complain of a high level of depression, and 20% complain of mild depression. In addition, the results found there association between uncontrolled glucose levels and depression. |

| 16 | Hilliard et al., [48] | 2011 | Adolescents with T1DM aged between 13-18 years Sample size: 150 |

Depression and anxiety | Cross-sectional design | All participants completed depression and anxiety screeners. After one year, blood glucose monitoring frequency and HbA1c values were measured. The results of this study indicate that higher HbA1c values correlated with depression and anxiety among adolescents with T1DM. |

Preferred reported items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) chart summarizing the selection.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were studies that (a) were published in the English language, (b) were full-text, (c) focused on depression and anxiety among adolescents, and (d) focused on type 1 diabetes. Articles were excluded if they (a) focus on parents, (b) do not have full text, or (c) focus on type 2 diabetes.

2.3. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

Using the PROBAST technique, which assesses the risk of bias and application of prediction model studies, two researchers evaluated the risk of bias in each study [20]. If the reviewers' scores differed, a third researcher was consulted to reach an agreement (Table 2).

| Sections | Domains | [21] | [35] | [45] | [22] | [14] | [23] | [46] | [32] | [33] | [37] | [13] | [28] | [10] | [47] | [25] | [48] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Is the basic study design valid for a randomized controlled trial? | Did the study address a focused research question? | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Was the assignment of participants to interventions randomized? | CT | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | |

| Were all participants who entered the study accounted for at its conclusion? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Was the study methodologically sound? | Were the participants rendered 'blind' to the intervention they received? Were the researchers 'blind' to the treatment they were administering to subjects? Were the individuals evaluating or studying the outcome(s) “blinded”? |

N N N |

N N N |

Y Y CT |

CT CT CT |

N N N |

N N N |

N N N |

N N N |

N N N |

N N N |

Y Y CT |

CT CT CT |

N N N |

N N N |

N N N |

N N N |

| At the commencement of the randomized controlled experiment, were the study groups comparable? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Did each research group receive the same standard of care (i.e., were they treated equally) aside from the experimental intervention? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| What are the results? | Were the intervention's effects thoroughly reported? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Was the estimation of the intervention or treatment effect's precision reported? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Are the advantages of the experimental intervention greater than the costs and negative effects? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Will the results help locally? | Can you apply the findings to your situation or to your local community? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Would the experimental intervention benefit the patients in your care more than any other current intervention? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study Characteristics

This systematic review highlighted a total of 16 articles (11 cross-sectional designs, 4 systematic reviews, narrative literature reviews, and 1 case study), which consider adolescents with T1DM depression and anxiety aged between 11 and 19 years.

3.2. Results of Individual Studies

3.2.1. The Levels of Depression and Anxiety among Adolescents with T1DM

Several studies indicated high levels of depression and anxiety among adolescents with T1DM [21, 22]. A study performed by Adal et al., [23] recruited 295 adolescents with T1DM; the depression rate was 12.9%, with high levels of anxiety among adolescents with T1DM. Furthermore, in a study performed by Habib et al., [24] that included 251 adolescents with T1DM, it was reported that 46% had depression and 40.1% reported anxiety. A study conducted by Watson et al., [22] found that of 77 adolescents with T1DM, 40% thought of harming themselves, and one of them experienced current active depression symptoms. About 32 patients complain of depression symptoms, and 20 complain of both depression and anxiety symptoms [22]. Another study indicated that among 30 adolescents with T1DM, 60% reported high levels of depression [25].

3.2.2. Signs and Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety among Adolescents with T1DM

Studies indicated that depressive symptoms were reported among newly diagnosed T1DM patients more than those who had lived with it for several years [26]. A case study conducted by Herman et al., [27] reported that female adolescents with T1DM complain of signs and symptoms of depression as thinking about complications in the future and feeling lonely. Most adolescents with T1DM reported anxiety concerning fear of needles, hypoglycemia, and using technology-related diabetes as glucose monitoring [28].

3.2.3. Relationship between Anxiety and Depression with Sex among Adolescents with T1DM

Several studies have found that anxiety and depression are associated with sex differences [29]. Goncerz et al., [14] reported higher levels of depression among female adolescents with T1DM compared to males. Similarly, anxiety levels were also found to be higher in female adolescents with T1DM than in their male counterparts [30].

3.2.4. Impact of Depression and Anxiety on Glycemic Control among Adolescents with T1DM

Depression and anxiety can negatively affect adherence to diabetes management protocols, including insulin administration, blood glucose monitoring, and lifestyle recommendations. Poor mental health among adolescents can lead to suboptimal glycemic control, increasing the risk of long-term complications like Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA), neuropathy, and retinopathy. Several studies reported that depression and anxiety have harmed the glucose level and HbA1c values, and adherence among adolescents with T1DM [21, 31, 32]. One study found that adolescents with T1DM were diagnosed with higher levels of anxiety associated with low-frequency time of measuring the blood glucose level and uncontrolled glycemic control [33]. In the other study, among adolescents with T1DM, results indicated a correlation between a higher rate of anxiety and poor self-management (r = −0.49, p < 0.01), and it was associated with uncontrolled HbA1c levels [10].

4. DISCUSSION

Adolescents with T1DM have particular challenges in managing their illness, and anxiety and depression can make it much harder to achieve ideal glycemic control [34]. The risk of long-term consequences such as retinopathy, neuropathy, and cardiovascular disease is increased by poor glycemic management, which is frequently indicated by raised HbA1c values. Glycemic outcomes and mental health conditions like anxiety and depression interact in a complicated way that involves both behavioral and physiological factors. Due to the developmental, social, and emotional characteristics specific to this stage of life, these mechanisms are particularly noticeable in adolescents.

Studies included in the current study aimed to illustrate the prevalence of anxiety and depression among adolescents diagnosed with T1DM. A systematic review conducted by Buchberger, Huppertz et al. [21], which included sixteen studies, confirmed that a significant number of young people with T1DM experience symptoms of anxiety and depression, which may compromise their ability to manage diabetes and maintain optimal blood sugar levels. These results, in our opinion, are consistent with the recommendations for routine psychosocial evaluation upon diagnosis and early screening for psychiatric comorbidity. Similarly, Jaser et al., [35], and Hapunda [36], performed studies to describe stress and coping strategies as an adjustment to their glycemic control. It was noted that over time, there was a strong correlation between the adolescents' use of primary control coping strategies, such as problem-solving, and secondary control engagement coping strategies, such as positive thinking, and a decline in quality of life issues and depressive symptoms. On the other hand, a higher likelihood of quality of life issues and depressive symptoms was associated with the adoption of disengagement coping methods, such as avoidance. It was reported that the impact of stress associated with diabetes on depressive symptoms and quality of life was mitigated by coping.

A single-center observational study performed by Goncerz et al., [14], found that adolescent girls with T1DM had depressive symptoms more commonly than boys in the population under study, and parents were more likely than teenagers themselves to report anxious symptoms in their children. Additionally, it was found that functional impairments were associated with higher HbA1c levels. Similarly, Reynolds et al., [37], conducted a cross-sectional retrospective study that found most adolescents with T1DM feel anxious, and females have higher anxiety levels than males.

In the same line, Herzer and Hood [33], noted that among adolescents with T1DM, symptoms of state anxiety are linked to less frequent blood glucose monitoring and inadequate glycemic management. Another study conducted by Nguyen et al., [13], aimed to ascertain the frequency and progression of anxiety and mood disorders in Dutch teenagers (12–18 years old) who have type 1 diabetes, as well as to look at factors that are correlated with the severity of the symptoms, such as parental emotional distress. It was noted that adolescents frequently experience anxiety and mood disorders, which are linked to preexisting disorders. Higher symptom severity was correlated with greater diabetic distress.

Additionally, behavioral pathways are a primary mechanism through which anxiety and depression impair glycemic control [38]. Adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) must adhere to a rigorous self-management regimen, including frequent blood glucose monitoring, insulin administration, dietary regulation, and regular physical activity. However, anxiety and depression can disrupt these essential behaviors in several ways, such as reduced adherence to treatment regimens, disordered eating patterns, sleep disturbance, and substance use [39].

To sum up, a variety of behavioral factors, including reduced adherence, disordered eating, and sleep disruption, as well as physiological pathways, including HPA axis dysregulation, catecholamine surges, and inflammation, are among the mechanisms that connect anxiety and depression to poor glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. These variables interact dynamically, frequently producing a vicious cycle that makes managing diabetes more difficult.

4.1. Implications For Future Practice, Research, Education, and Administration

Taking care of depression symptoms in adolescents with T1DM has significant effects in several areas. Healthcare professionals should combine diabetes management with mental health support in a multidisciplinary manner. It's critical to regularly examine teenagers with T1DM for depression symptoms. Additionally, adolescents with T1DM and depression should get individualized psychological interventions such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) or mindfulness-based techniques as part of their treatment regimens. For research, long-term designs are required to examine the course of depressive symptoms in adolescents with T1DM and how they affect the results of diabetes care. Besides, it is necessary to conduct more prospective research in the future to create evidence-based treatment models and investigate how anxiety and depression symptoms interact with type 1 diabetes.

Beyond glycemic management, adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM) frequently deal with a variety of complicated issues, such as increased risks of anxiety and depression because of the chronic nature of the disease, lifestyle changes, and social pressures [7]. A more comprehensive approach to care might be offered by interprofessional collaboration, which brings together endocrinologists, psychologists, nurses, dietitians, and social workers [40]. These experts could be better able to identify and handle the emotional and psychological pressures that these teenagers face if they receive joint training in Interprofessional Practice and Education (IPE).

For example, many implications of this review could focus on how IPE programs, such as case-based training or shared workshops, can enhance patient outcomes by coordinating medical and psychological treatment. This could entail investigating how a team-based strategy could lessen anxiety through peer support initiatives or lessen depressed symptoms by incorporating mental health screenings into regular diabetes care [41].

For future education, training programs in identifying and managing mental health concerns in chronic illnesses should be part of the medical and nursing curriculum, with a special emphasis on the care of adolescents by engaging the patient in the educational program that could assist them in recognizing the depressive symptoms and initiate the conceptualization of patient-centered care [42-44].

For administration, health care administrators should create guidelines that include mental health screening in the treatment of diabetes among adolescents. This includes the requirement for mental health evaluations during regular check-ups for diabetes.

5. LIMITATIONS

This review has several limitations that can impact the quality and comprehensiveness of the review. Firstly, small sample sizes in studies involving specific populations like adolescents with T1DM can weaken statistical power, leading to overstated conclusions or missed effects. This can also make it difficult to account for confounding variables like age, socioeconomic status, or disease duration, and the majority of studies on depression and type 1 diabetes concentrate on either adults or children. For this age range, it can be challenging to draw clear conclusions. Secondly, the variability in evaluation instruments used to measure depressive symptoms, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), as well as the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory tool. So, it may be difficult to compare the findings of different studies because of this inconsistency. Thirdly, cross-sectional designs capture data at a single point in time, but cannot establish causality or track mental health challenges over time. This design flaw limits understanding of the dynamic interplay between T1DM and psychological well-being, as it does not establish whether T1DM causes depression or anxiety in adolescents. Finally, self-reported outcomes in adolescents can be challenging due to stigma, self-awareness, and self-reported symptoms. Accuracy depends on self-awareness and willingness to be honest. Studies risk bias without objective measures, reducing confidence in prevalence rates or the severity of depression and anxiety.

Future research with larger, more diverse samples, longitudinal tracking, and mixed methods (combining self-reports with clinical diagnoses) would provide a sharper picture and offer better support for these adolescents.

CONCLUSION

Addressing mental health in adolescents with T1DM is critical for their overall well-being. A multidisciplinary approach involving medical professionals, mental health experts, and families can help adolescents manage both their physical and emotional health effectively. This review revealed that depression and anxiety among adolescents with T1DM harmed HbA1c levels and glycemic control. Besides, a systematic review on depression and anxiety among adolescents with T1DM highlights the importance of managing mental health challenges for better disease management, fewer complications, and improved quality of life through fund longitudinal studies with larger, diverse cohorts to track how depression and anxiety evolve with T1DM over time, clarifying causality and long-term impacts. It is also recommended to integrate mental health screening into routine T1DM care by utilizing validated assessment tools to identify at-risk adolescents at an early stage. Maintaining effective interventions to assess or treat depression and anxiety among adolescents with T1DM can enhance adherence to treatment plans and improve quality of life by enhancing glycemic control and relieving symptoms of anxiety and depression.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: S.M.: Responsible for the study conception and design; S.B.H.: Contributed to data interpretation and synthesis of findings; H.A.S.: Handled the methodology and investigation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| T1DM | = Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus |

| IDF | = International Diabetes Federation |

| PRISMA | = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PHQ | = Patient Health Questionnaire |

| BDI | = Beck Depression Inventory |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All the data and supporting information are provided within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.