All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Results of a Survey Among Adult Patients on the Appearance of Nurses in Italy

Abstract

Background

Appearance is fundamental in nonverbal communication. Moreover, the uniform is a visual symbol identifying the professional figure and related prerogatives in a relatively short time. Nonetheless, the ideal nurse uniform is still debated.

Objectives

This study aimed to explore the preferences of Italian adult patients regarding the attire of nurses.

Methods

A questionnaire was developed and validated to survey patients in the waiting rooms of the University Hospital of Sassari, Italy. Each participant was asked to answer six questions related to the study topic and to choose one picture from a selection of different attires (white uniform, casual uniform, scruffy clothing with uniform, solid-color uniform, and classic and trendy outfits) from both sexes.

Additional details, including name tag, hair length, jewels, makeup amount, body art, and piercing, among others, were also evaluated.

Results

From November 2020 to November 2021, a total of 864 questionnaires were completed (60.9% by female patients and 49.1% by male patients). Most patients preferred white (46.4%) or solid color (47.84%) uniform, independent of age or educational level. Casual attire was preferred by a minority of patients (0.92%). The entire sample judged inappropriate long hair, visible tattoos, body piercings, sports shoes, and long nails. Moreover, wearing jewels and excessive makeup for female nurses and long beards for male nurses scored very low.

Conclusion

This is the first study conducted in Italy regarding the attire of nurses, and similar to other Western countries, nurses with a white or solid color uniform were preferred. Wearing a professional dress is part of non-verbal communication and may favorably influence nurse-patient interaction and, in turn, patient adherence to treatment.

1. INTRODUCTION

A symbol is an element of communication representing a concept or quantity (e.g., an idea, an object, a quality). It is a sign that can be i) conventional, under a social convention, or ii) analogical, i.e., capable of evoking an association between a concrete object and a mental image [1]. For example, spoken language consists of distinct auditory elements representing symbolic concepts (words) arranged in an order that further specifies their meaning. Symbols have an intersubjective solid character, as they are shared by a social group. In particular, symbols differ from signals since the latter have a purely informative and non-evocative significance. Symbols also differ from brands, which have only a subjective matter.

The word symbol derives from the Latin symbolum and, in turn, from the Greek σύμβολον “sùmbolon” having the meaning “together”, the connection of two distinct parts. In ancient Greece, the term symbol had the purpose of an identification card. Usually, the relationship between symbols and what they represent is conventional and not solely an imitation. Furthermore, it plays a key role in nonverbal communication [2]. Accordingly, the “uniform” identifies the wearer, indicating belonging to a specific category. Its goal is to recognize groups of people (doctors, soldiers, priests, etc.) who perform the same function within a particular setting. The type, color, and cut should be the same for all category members [3]. Therefore, the uniform of nurses immediately identifies the professional figure and related prerogatives [4].

Nursing uniforms have changed over time, following scientific and industrial revolutions, leading to modifications in the hospital organization [5]. Nursing became an acknowledged profession in the 1800s [6].

Primarily considered a women's role, the original nurse uniform consisted of a high-collared shirt, a floor-length tabard dress, and a bonnet. They were worn to hold hair back, while aprons were used to protect garments from medical solutions, biological secretions, and infected fluids [7]. The first known example of a nursing uniform was introduced by Florence Nightingale, who was a nurse manager and trainer during the Crimean War in 1855 [8]. It consisted of a full-length dress with long sleeves and an apron. Moreover, nurses wore a white sash with embroidered “Scutari Hospital” in red and a white cap resembling a nun's clothing. Nurses did not wear gloves or masks at that time to protect them. In addition to acting as a barrier from infection, the uniform was an important visual symbol to ensure nurse recognition by patients and doctors. In 1860, Nightingale founded the first nurses' school, and accordingly, a teaching method based on education hierarchy, discipline, dedication and high standards of behavior. According to the modern practice of nursing established by her, the first private school was founded in Italy between 1800 and 1900 [9, 10]. She also inspired Red Cross founder Henry Dunant, who advocated the formation of national voluntary relief organizations to care for wounded soldiers during wartime [11]. The undisputed symbol of the Red Cross was the red Helvetic cross sewn on the chest or the armband.

Through the 19th and 20th centuries, the uniform changed into a more practical outfit able to distinguish nurse hierarchy [12]. White color was the primary choice for nurses' uniforms (1915-1945). The overtime changes in nurse uniforms reflected social evolution in the healthcare system [10, 13]. Nowadays, practicality has become a priority; however, views on the nursing uniform are conflicting [14]; traditional clothing symbolizes history, and the meaning ascribed to the white uniform is purity and cleanliness. According to Smith [15], the uniform represents a sort of legitimation; it suppresses individuality and creates a totem. It also establishes distance between nurse and patient, revealing the wearer's authority and a sharper professional identity, as demonstrated in Italian nursing students [16]. On the other hand, especially in the United States, this kind of distance between healthcare professionals and patients is abolished by using various solid-colored uniforms, not considered authentic uniforms [17].

The fundamental issue revolves around activities or jobs that involve close contact with a specific group of people, in particular patients, implying the possibility of being identified immediately by the patient, regardless of words (explanations), avoiding confusion with other professional figures [18].

Given the symbolism attributed to a uniform, people expect that the person wearing a particular uniform can act in a specific way [19]. Although attire might not affect healthcare activities, the instinctual patient's perception of a nurse figure can influence his/her compliance to share confidential information, health education, therapeutic interventions, and so on [20]. In a review by LaSala et al., it was highlighted that appearance, behavior, dress, and communication skills made an essential contribution to the image of professionalism projected by nurses. For all these reasons, dresses, make-up, hairstyles, jewelry, piercings, and body art may strongly impact the patient-nurse interaction [21].

Several authors have evaluated the role of standardized clothing of the nurse figure with contrasting results [22-24]. However, patients prefer nurses with a professional appearance because it is thought to improve nurse-patient interactions [25, 26].

In particular, the use of casual clothes by nurses has been advocated with the aim of improving nurse-adult-patient relationships [27]. Casual clothes may be considered more practical by nurses; however, patients—through questionnaires— expressed the belief that the abolition of the uniform could make it challenging to identify these figures, especially during emergency situations [27]

In Italy, no studies are currently available regarding patients' preferences for nurses' clothing; for this reason, we conducted a survey on a large convenience sample using a previously validated questionnaire.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design and Setting

The present study was a cross-sectional study based on a survey method through the administration of a questionnaire to a convenience sample of adult patients in the waiting rooms of the University Hospital of Sassari, Italy.

2.2. Participants

The interviewed cohort was from Northern Sardinia, an Italian region immersed in the Mediterranean Sea with over one and a half million inhabitants. It is administratively divided into four provinces: Sassari, Nuoro, Oristano, Cagliari, and 377 municipalities. It has a territory of 24,090 km2, making Sardinia the third largest region in Italy. Until World War II, the Mediterranean island of Sardinia was considered a “low-resource” region compared with mainland Italy. However, after the eradication of endemic malaria, the island underwent rapid economic development, improving the population's standard of living [28]. A homogenous socio-cultural background characterizes the Sardinian population.

2.3. Inclusion/exclusion Criteria

The survey was performed by using a questionnaire developed based on a model by Campbell et al. [4]. The questionnaire was validated in a sample of physicians and nurses to test its clarity, simplicity, reliability, and validity. Subsequently, the questionnaire was administered to 30 volunteers who did not find any difficulty filling it. After a month, the questionnaire was redistributed to the same volunteer group to verify the consistency and reliability of the answers. The pilot test yielded approximately 90% reliability.

Healthcare professionals explained the purpose of the study to patients in the hospital's waiting rooms in simple words and asked them to complete the questionnaire. Patients participated in the survey on a voluntary basis. Filling out the questionnaire took approximately 5 to 10 minutes.

2.4. Structure of the Questionnaire

The authors used the questionnaire in a previous study to evaluate doctors’ attire [29]. It briefly consists of two main sections: the first part focuses on demographics (e.g., sex, age, education, and profession), and the second part contains seven questions related to the aim of the study. In addition, tables listing details of the whole appearance of the nurses and pictures showing female and male nurses in different attires were included.

The following questions were listed in the second part of the questionnaire.

1. Have you ever been hospitalized? In medical wards? In surgical wards?

The question allows for distinguishing between people who have had direct experiences and close contact with healthcare personnel and those who have not.

2. What does the nurse represent for you…………

To answer this question, the patient had four options: i) a doctor subordinate (meaning a secondary role of lesser importance or value, of a lower order than the doctor, having a passive role); ii) a doctor-patient mediator (between two or more cultures or social status, sometimes very distant from each other in order to encourage adherence to a given treatment or procedure by providing them assistance, etc.); iii) a confidant (a person you trust and to whom you confide your secrets, emotions, fears, and anxiety), or iv) a professional (anyone who carries out an activity for which a qualified competence is required. In this specific case, the healthcare professional is an operator who provides preventive, curative, promotional, or rehabilitative healthcare services in a systematic way to people, families, or communities).

3. Did you experience difficulties recognizing nurses from the other health professionals in hospitals and clinics?

The question aimed to verify whether using anonymous and different uniforms induces confusion among patients in identifying nurses across healthcare operators.

4. Would it be appropriate for the nurses' uniform to be the same for everyone, or they could choose it based on their preferences?

The question is a crucial point for understanding how important it is for patients that nurses are represented by a standard outfit defining their substantial role and features.

5. Should the head nurse wear a different uniform?

The question aims to determine whether an authoritative and coordinating figure in the ward or clinic is important for the patient for any problem that cannot be solved by nurses.

6. Add a cross for each question: i) I like it, ii) I don't like it, or iii) irrelevant, according to your preference.

In Table 1, a number of details concerning the nursing attire are listed to better define the most critical characteristics, making the dress of the nurses more professional for patients.

The questionnaire also included a list of details concerning female nursing attire similar to Table 1, with the exception of questions related to beard (beardless, neat beard, and long beard) and additional questions, such as loose long hair, long collected hair, colored hair (with unusual colors such as pink, light blue, green, etc.), heavy make-up, light make-up, long nails with polish, and jewelry (besides ring and watch).

7. Choose the image that best reflects how the ideal nurse should look.

Patients had the opportunity to choose among multiple photos, as shown in Fig. (1).

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the local institutional review board (the General Management of the Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria of Sassari and the Medical School and Nursing School, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy). According to Italian law [30], the survey did not require ethics approval. Participation in the study was on a voluntary basis, and the questionnaire was anonymous.

| Male Attire | I like it | I do not like it | Indifferent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Name tag | |||

| Formal, classic clothing | |||

| Casual clothing (jeans and T-shirt, jeans and more) | |||

| Uniform | |||

| Perfume | |||

| Classic shoes | |||

| Sport shoes | |||

| Clogs | |||

| Sandals | |||

| Without socks | |||

| Long hair | |||

| Short hair | |||

| Beardless | |||

| Neat beard | |||

| Long beard | |||

| Overweight/obesity | |||

| Clean teeth | |||

| Long nails | |||

| Short nails | |||

| Earrings (piercing), necklaces | |||

| Tattoos |

Photos representing different attires for male and female nurses. A) white uniform; B) scruffy clothing with uniform; C) solid colored uniform; D) classic trousers and uniform jacket; E) casual clothing; and F) trendy clothing.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Consecutive patients who gave their verbal consent to participate were enrolled. It was established that the sample size had to be at least 750 participants. Qualitative variables were evaluated using the chi-square test. Student's t-test and Mann-Whitney test were used for quantitative variables with parametric and non-parametric distribution, respectively. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were collected in a standard electronic form and analyzed using Stata 9.0 (StataCorp, Stata Statistical Software Release 9, College Station, TX, USA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Sample Characteristics

A total of 864 questionnaires were collected over a period of 11 months. More represented age decades were the fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh (Table 2), and 60.9% of study participants were females. Overall, 80% of interviewees were hospitalized at least once, more specifically, 51.9% in a medicine ward and 62.2% in a surgery ward.

| Variables | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | - |

| Male | 330 (39.1) |

| Female | 514 (60.9) |

| Age groups | - |

| <20 | 55 (6.5) |

| 20‒29 | 97 (11.5) |

| 30‒39 | 149 (17.7) |

| 40‒49 | 175 (20.7) |

| 50‒59 | 164 (19.4) |

| 60‒69 | 105 (12.4) |

| 70‒79 | 78 (9.2) |

| 80‒89 | 18 (2.1) |

| ≥ 90 | 3 (0.4) |

| Education | - |

| None | 4 (0.5) |

| Primary school | 148 (17.5) |

| Lower secondary school | 228 (27.0) |

| Upper secondary school | 299 (35.4) |

| University | 165 (19.5) |

| Have you ever been hospitalized? | - |

| No | 175 (20.7) |

| Yes | 669 (79.3) |

The majority of patients (52.1%) perceived the nurse as a professional figure of the healthcare system, and 71.2% did not have difficulty identifying nurses. Accordingly, 79.6% of patients agreed that nurses should wear the same uniform to recognize the category, except for the head nurse (74.4%) (Table 3).

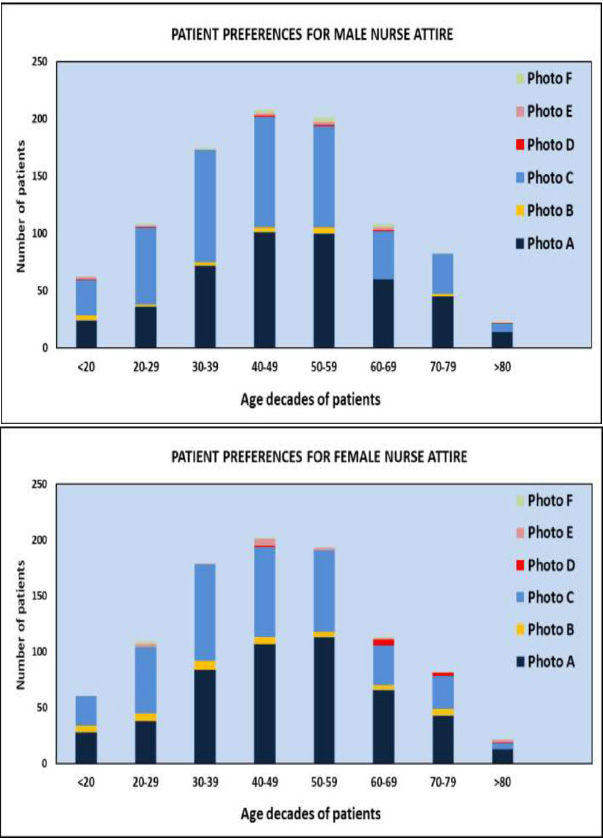

The uniform most frequently chosen for male and female nurses was the white and solid-colored uniform across all participants' age decades (Fig. 2).

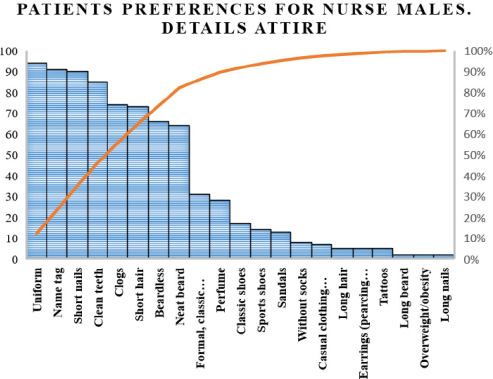

Fig. (3) illustrates the preferences of the patients for attire details. In particular, long nails, overweight and obesity, long beards, tattoos, piercings, and long hair did not meet patients' appreciation of male nurses. For example, loose, long hair can get on the face of the nurse or be contaminated by various secretions, posing hygiene and safety problems for both the nurse and the patients.

| Questions | Answer Number (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| What does the nurse represent for you? | - | - |

| Doctor's subordinate | 146 (14.9) | - |

| Mediator | 159 (18.8) | - |

| Confidant | 44 (5.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Professional | 440 (52.1) | - |

| I don't know | 75 (8.9) | - |

| Did you experience any difficulties in recognizing nurses from other health professionals? | - | - |

| No | 601 (69.5) | - |

| Yes | 232 (26.8) | < 0.0001 |

| I don't care | 31 (3.5) | - |

| Would it be appropriate for nurse uniforms to be the same for everyone, or could nurses choose them based on their preferences? | - | - |

| Equal uniforms | 679 (78.6) | - |

| Various uniforms | 115 (13.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Not relevant | 70 (8.1) | - |

| Should the head nurse wear a different uniform? | - | - |

| Yes | 639 (73.9) | < 0.0001 |

| No | 225 (26.1) | - |

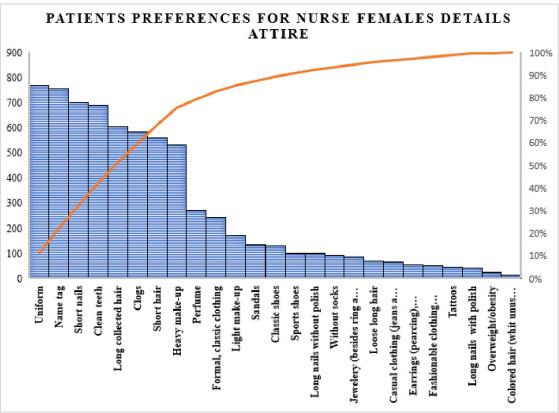

As for the clothing of the female nurses, in addition to the aspects judged negatively in male nurses, heavy make-up, overweight/obese, long nails with polish, jewelry (besides ring and watch), and body art were found to be inappropriate (Fig. 4).

4. DISCUSSION

Nurse attire can be a fundamental key in patient-nurse interaction. It has been reported that “competence”, “confidence”, and “credibility” are judged by others in the first 12 seconds of an interaction, which includes attire [31].

Our survey showed that Italian adult patients prefer professional attire over casual, traditional, trendy, or more nonchalant clothing. These results agree with a previous study conducted in the Cleveland Clinic (Cleveland, OH, USA) on adult and pediatric patients and hospital visitors [32]. Adult patients preferred solid colors and white uniforms because they considered this type of clothing to be associated with nurse professionalism traits (e.g., confidence, competence, attentiveness, efficiency, approachability, and care, among others) [32]. Porr et al. conducted a similar study in Canada [25]. The authors

1. Distribution of patients' preferences for male. 2. Female nurse uniforms according to age decade. A) White uniform; B) scruffy clothing with uniform; C) solid colored uniform; D) classic trousers and uniform jacket; E) casual clothing; and F) trendy clothing. The different colors in the histograms indicate the frequencies of respondents' preferences according to the uniform shown in the different pictures. The deep blue (photo A) and light blue (photo C), corresponding to the white and colored uniforms, are the most represented in both sexes, while the remaining attire (scruffy, casual clothing, trendy, and classical) rated very little appreciation.

Preferences of patients about look details of male nurses. Blue light bars indicate the number of study participants who appreciated the details of the specific attire (who answered, “I like it”). The orange line shows the number of participants who did not appreciate some details (who answered “I do not like it”).

Preferences of patients about look details of female' nurses. The blue light bars indicate the number of study participants who appreciate the details of the specific attire (who answered, “I like it”). The orange line shows the number of participants who do not appreciate the exact details (who answered “I do not like it”).

showed photographs of the same nurse in eight different uniforms of adult patients. In line with our findings, the white pantsuit scored higher for professionalism than other kinds of uniforms [25]. Several years earlier, a literature review about patient perceptions of nurses' attire, conducted by Lehna et al., had reached the same conclusions: patients still preferred traditional white dress. However, other forms of clothing were acceptable [33]. In a multicenter study conducted in acute care hospitals across Utah, 2,430 respondents, including patients, nurses, and administrators, were surveyed regarding their first impression of the professional image of nurses' uniforms, which showed that white pant uniforms with stethoscopes rated significantly higher than other uniforms. In comparison, colored designer scrubs and white pants with a colored top obtained the lowest score [34].

Unfortunately, Italian studies on the same topic conducted in adult patients are not available to compare with our results. Instead, a similar survey was conducted on children admitted to a pediatric hospital [35]. In contrast to our findings, the impact of a multi-colored, non-conventional attire was shown to be preferred by the pediatric population and their parents. The authors concluded that child preferences can improve the child–nurse relationship and have the potential to reduce the discomfort given by hospitalization. A more recent Italian study also extended to nurses, as well as children, confirmed previous findings, with the color uniforms being the most chosen [36]. These results are reasonable for children. For example, in a study reporting the rationale for their choice of a specific attire, mothers explained that they did not like white uniforms because their children were afraid of nurses wearing white uniforms [37]. However, in the same study, military veterans preferred white uniforms because they were associated with professionalism and cleanliness [37]. More importantly, adult patients perceived nurses with white uniforms as associated with greater competence, followed closely by the lab coat over street clothes [37].

In addition to the type of clothing, the attire may be completed by details, such as hairstyle, jewelry, make-up, and so on, which can impact the patient-nurse relationship and, in turn, patients' adherence [20, 21].

Our study revealed that some details, such as long nails, overweight or obesity, long beards, tattoos, piercings, and long hair in male nurses, and heavy make-up, overweight/obesity, long nails with polish, jewelry (aside from ring and watch) and body art in female nurses scored very low. More importantly, significant differences between age-decade groups about perceptions regarding piercings and tattoos were not detected. A study by Newman et al. conducted among patients in the emergency department showed that visible nontraditional body art negatively impacts first impressions [38]. Similar to our findings, the authors found that for a sizable proportion of respondents, facial piercings were inappropriate for physicians [38]. Thomas et al. observed that visible tattoos and piercings are associated with poor caring skills among nurses, students, and faculty personnel [26]. Although there is a growing trend of individualism and, therefore, the right to express oneself anyway, and everywhere, including the workplace, especially from “Generation Next”, visible body art and unconventional piercing are also growing among nurses. However, according to Thomas, “the nurse is there to help patients heal, not to subject them to their right of self-expression” [26].

Data about the preferences of patients for overweight/obese nurses are limited. However, previous studies across different countries [39], including Italy, reported weight stigma (stereotypes, rejection, prejudice, criticisms, and so on) in more than 50% of the obese individuals interviewed [40]. It is, therefore, not surprising that nurses can also evoke body weight stigmatization by patients.

Overall, our findings highlight how external appearance is not a negligible component in the nursing profession. Even details, such as visible underwear, rumpled uniforms, and pants that are too long or too short negatively affect patient and visitor perception [32]. Attire is part of non-verbal communication, representing the first means of interaction; thus, a scruffy appearance, not appreciated by the patient, might compromise the professional relationship [32]. Nonetheless, the uniform is a visual and instantaneous symbol that enables patients to identify nurses immediately [34]. Nowadays, casual, unconventional clothing is gaining popularity even among doctors. Another survey on patients' preferences about physician attire, conducted in the same hospital, similar to the findings obtained for the nurse attire, showed that the majority of patients preferred conventional outfits (surgical uniform or formal dress under a white coat with a name tag) [29]. Trendy attire was preferred by a minority (1.1%). Moreover, long hair, visible tattoos, piercings, wearing trousers, and excessive make-up for women were considered unsuitable [29].

Misidentifying the professional roles may confuse the patients, wasting time and resources in explanations [32]. In addition, the casual clothing of the nurse may result in less hygiene [18]. In these circumstances, casual clothes are laundered at home or in a private offsite laundry by inadequate laundering processes. This may pose a severe problem for microorganism contaminations in an era where nosocomial bacterial resistance has increased, leading to significant morbidity and healthcare costs.

This study has several limitations. Based on its cross-sectional design, it did not allow evaluation of differences over time. Moreover, it was based on a probably culturally specific instrument, at least for some elements, which do not necessarily reflect current social expectations. Some items may be missing (e.g., mobile phone, with or without earphones, pins or other ornaments hanging from the uniform, etc.). Using convenience sampling and participants of the same ethnicity and demographic characteristics may reduce the generalizability of our results to the populations of other countries.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, our findings confirm preferences for the traditional attire of nurses among a large cohort of patients across different generations. If confirmed, the results of this study might guide healthcare facilities to set up dress codes compliant with the wishes of patients, aiming to increase their adherence to diagnostic tests, treatment, and follow-up.

Furthermore, considering that the “school,” and in particular, the school of nursing, not only educates but especially trains professionals, the results of our study could contribute to the process of “knowing how to be” as well as “knowing how to do.”

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the local institutional review board CE 234/2018 (the General Management of the Azienda Ospedaliero Universitaria of Sassari and the Medical School and Nursing School, University of Sassari, Sassari, Italy).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Participation in the study was on a voluntary basis, and the questionnaire was anonymous.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Nurse A. M. for contributing to the creation of the photographs of the nurse in different types of clothing used for the study.