All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Nursing Internship in Pre-registration Nursing Education Programs: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Background

A nursing internship is a program for the transition of nursing students to practice as registered nurses, preparing them to face real life in the clinical environment. A well-structured nursing internship program could promote clinical competency, caring ability, and self-confidence in dealing with complex clinical environments.

Objective

This scoping review aimed to synthesize the knowledge of existing literature on pre-registration nursing internship programs.

Methods

This review was conducted following a methodological framework for a scoping review, identifying the research questions, exploring relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, and collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. Literature searches were conducted in the databases, including Medline, CINAHL, Ovid, and ScienceDirect.

Results

It was found that the caring ability, perceived level of competency, and self-efficacy of nursing interns were likely to improve after completing the internship. Nursing interns had both positive and negative experiences of undergoing internship programs. Positive aspects of a nursing internship included filling the theory and practice gap and improving self-confidence, independence, and readiness for practice. Challenges encountered were insufficient support, workload, being involved in non-nursing work, transition shock, and feeling lost.

Conclusion

The nursing internship programs effectively bridge theoretical knowledge with practical skills, fostering professional growth, clinical competency, and communication abilities. The concerning issues, such as burnout, transition shock, and limited critical thinking development, highlight the need for improvements in support systems and curriculum design.

1. INTRODUCTION

Clinical learning experience is an important part of nursing education, especially in the pre-registration nursing curricula. In designing a pre-registration nursing education program, the key program objective is to produce graduate nurses who are competent in providing quality and safe care to the public. To achieve this objective, the nursing faculty needs to develop a curriculum that sufficiently covers theoretical knowledge as well as clinical practice experience.

In some countries, the nursing internship course is incorporated in the final year of the Bachelor of Nursing program or at the end of the final year academic program prior to registration and licensure endorsed by the board of nursing in the respective countries. The nursing internship is a program for the transition of nursing students to practice as registered nurses, with an aim to facilitate role changes, enhance core competency, and create a clear understanding of real life in a clinical environment [1]. As such, a nursing internship helps familiarize student nurses with the day-to-day aspects of clinical settings and prepares them for their transition to registered nurses when they graduate.

Several studies have been conducted, both quantitative and qualitative studies, investigating nursing interns’ perceptions and outcomes of nursing internship programs. The findings indicated that the internship courses improved clinical practice and caring ability, teamwork, communication, and interpersonal skills [2-4]. Moreover, internship programs have been observed to increase the self-confidence, critical thinking, and clinical competence of students [4]. These findings suggested that the implementation of a well-structured nursing internship course could be considered in curriculum development.

For the further development of a well-structured internship program, a review of scientific literature and evidence-based recommendations are warranted. This scoping review aimed to synthesize the knowledge of existing literature on pre-registration nursing internship programs implemented worldwide.

2. METHODS

The review was conducted following a methodological framework for a scoping review guided by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), which involves five stages: 1) identifying the research questions, 2) exploring relevant studies, 3) study selection, 4) charting the data, and 5) summarizing and reporting the results [5]. Each stage of the review is outlined in the sub-sections.

2.1. Identifying the Research Questions

The research questions for this scoping review are: 1) What are the duration and delivery of the pre-registration nursing internship program? 2) What are the outcomes of the internship programs in undergraduate nursing education? 3) What are the nursing interns’ perceptions of internship programs? and 4) What are the experiences and challenges of undergoing nursing internship programs?

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

The relevant studies to be included in the review were identified through electronic databases. Literature searches were conducted in the databases, including Medline, CINAHL, Ovid, and ScienceDirect. The search was conducted between July and August, 2024. The keywords used to search the relevant literature were internship, nursing, nurse interns, pre-registration, and undergraduate. Then, the relevant studies were identified based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

This review focused on pre-registration nursing internships in general clinical practice rather than internships in specific conditions or specialised care settings. The inclusion criteria of the studies were: a) original research focusing on pre-registration nursing internship, b) study population involved undergraduate nursing students or nurse interns involved in pre-registration internship programs in acute care settings, and c) published in English. The exclusion criteria were: a) review or protocol papers, b) grey literature, c) studies on newly graduated nurses or interns in the post-registration course, d) studies with a focus on an internship in specialty areas, such as intensive care, palliative care, geriatric, psychiatric and community health settings, and e) studies focused on a specific aspect of nursing care practice during internships, such as medication error, diabetic management, and utilisation of nursing process. Types of study included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies, which are relevant to answer the identified research questions. The year of publication was limited to 10 years, from 2014 to current.

2.3. Study Selection

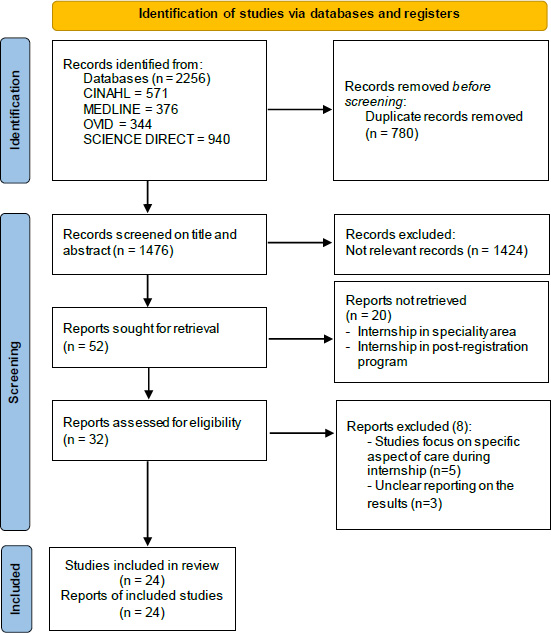

A total of 2231 articles were identified from the electronic databases, and 25 articles were from cross-references and other sources. After the duplicate records were removed, 1476 articles were left; the titles and abstracts of articles were screened and assessed for eligibility. Then, 32 full-text articles were retrieved. Of these 32 full-text articles, 24 articles that met the scope and criteria were included in the final review. The PRISMA flow diagram is shown in Fig. (1).

2.4. Data Extraction and Charting

In this stage, the authors extracted the relevant information that answered the research questions. The information about the authors (year) and country, research objectives, study design, sample and setting, outcomes or measurement tools in quantitative studies, data collection, analysis methods used in qualitative studies, duration and structure of internship program, and key research findings were extracted.

2.5. Summarizing and Reporting the Results

In this stage, the extracted data were presented in a descriptive summary. Data synthesis examined similarities and differences in study findings, with a specific focus on the delivery were reported in the summary table and narrative accounts to answer the specified research questions.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Overview of the Studies Included in the Review

A total of 24 studies were included in this scoping review: 12 quantitative studies, nine qualitative studies, and three mixed methods studies. The majority of the studies were conducted in Saudi Arabia (14 studies), followed by Iran (5 studies), and then three studies from China and the other two studies from Turkey. The study objectives and measurement variables were diverse across the studies. The summary characteristics of the studies are presented in Table 1 for quantitative studies and Table 2 for qualitative and mixed methods studies.

3.2. Duration and Delivery of Nursing Internship

Overall, most of the internship programs described in the reviewed studies were designed with 1-year duration in the final year of the Bachelor of Nursing program. Internship students were assigned to work independently but under supervision in general acute care settings and some of the specialty areas.

In Saudi Arabia, the nursing internship program is 12 months long (52 weeks), which is a mandatory requirement to sit for the nursing registration exam [6-9]. The internship year commences after completing the fourth-year academic program. The clinical placement during the internship includes medical-surgical, critical care, pediatrics, maternity, intensive care, and emergency wards [6, 7, 10]. In addition, intern nurses are exposed to psychiatric and primary health care, the operating room, triage area, outpatient clinic, dialysis, and endoscopy. The nurse interns work under the supervision of a nursing preceptor, and they are required to obtain a total score of 60% to pass the evaluation [11].

PRISMA flow diagram.

| Authors, Year [Ref] & Country |

Study Objective (s) | Study Design, Settings & Sample (N) | Outcomes/ Measurement Tools | Duration and Description of Internship Program | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelkader et al., 2020 [2] Saudi Arabia. |

To identify perceived level of preparation in the internship program. | Design: Descriptive exploratory Setting: College of Applied Medical Sciences/King Faisal University Sample: Nurse interns (N = 121). |

Clinical preparation requirements electronic survey. | Not reported. | Majority of the respondents gave their highest percentage for educational preparation requirements with teaching & information giving, psychomotor skills and communications skills (79.70%, 78.82% and 76.92% respectively). |

| Hu et al., 2022 [3] China. |

To measure and compare nursing students’ caring ability before and after internship. | Design: Descriptive longitudinal study Settings: Nursing school together with three internship hospitals Sample: Nursing students who had undergone internships during 2018-2020 in three hospitals in Changsha (N=305). |

Caring ability inventory. | 1-year internship, after completing 3 years basic nursing and medicine The preparation section had three phases: hospital assignment, pre-internship training, and mobilization meeting. Internship section included five phases: preceptors’ selection and training, unit introduction, preceptorship, post-preceptorship examination, monthly feedback and adjustment, mid-term nursing rounds, and summary meeting. |

The overall score of caring ability and scores of cognitive and patience dimensions were higher after internship than before internship. There was no significant improvement in the courage dimension. |

| Albloushi et al., 2023 [6] Saudi Arabia. |

- To compare the level of perceived clinical competence among undergraduate nursing students before and after completing the internship year - To explore the relationship between the participants’ characteristics and perceived clinical competence level. |

Design: A cross-sectional, comparative study Settings: 13 public and private nursing schools Sample: Nursing students in the last period of their fourth year or in the last 3 months of their internship year (N=244). |

The Clinical Competence Questionnaire (CCQ). | 1-year program as a requirement to sit for nursing registration exam. Clinical rotation in different areas such as emergency, medical-surgical, pediatric, and maternity wards. |

Internship nursing students perceived themselves as more competent in performing nursing skills without supervision than fourth year nursing students. Female students perceived that they had higher competence compared with male students. |

| Aljohni et al., 2023 [7] Saudi Arabia. |

To assess internship-level nursing students’ perception of their CLES, and to identify associated factors. | Design: Cross-sectional design Settings: Public university in Saudi Arabia, Colleges of Nursing. Sample: Internship-level nursing students (N=250). |

Clinical learning environment, supervision, and nurse teacher instrument (CLES + T). |

12-month-long (52 weeks) internship year prior to graduating and working as registered nurses, required by the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS). Students are exposed to several nursing care specialties; emergency, intensive care, medical-surgical, pediatric, maternity (for female students only), psychiatric, and primary health care. |

Students reported a positive view regarding their CLES (M = 3.76 ±0.64), with the sub-dimension regarding the role of the nurse educator (NT) scoring the highest compared to other subdimensions. Female interns reported more positive view of their CLES compared to male interns. A weak positive correlation was observed between students’ perception of their CLES and GPA. The role of the NT was perceived most positively by students. |

| Almadani et al., 2024 [10] Saudi Arabia. |

- To assess nurse interns’ perceptions of their clinical preparation and readiness. - To examine relationships between perceived preparation and perceived practice readiness. |

Design: Cross-sessional Setting: College of Applied Medical Sciences, Hafr Al Batin University Sample: Nurse interns enrolled in their internship year (N=130). |

Clinical preparation requirement questionnaires casey–fink readiness for practice survey. |

1-year internships in the fifth year BSN program, rotate through different clinical settings in medical-surgical for pediatrics and adults, critical care, intensive care units, the emergency room, the operating room, triage area, dialysis units, labor and delivery units, and outpatient clinic. |

Nurse interns had a moderate level of clinical preparation, and 28.5% of them exhibited a low level. 53.8% were found to be moderately ready for practice, while 22.3% had a low level of readiness There was a highly significant correlation between the readiness for practice and clinical preparation requirements. |

| Alaamri et al., 2024 [11] Saudi Arabia. |

To assess the psychological readiness of the nursing intern for a professional position. |

Design: Cross-sectional Setting: King Abdul-Aziz University (KAU), School of Nursing Sample: Nursing interns undergoing their internship year (n=44). |

The Casey–Fink Readiness for Practice Survey (CFRPS). | 12- month duration The clinical placement during internship: medical-surgical, pediatrics, maternity, emergency, intensive care, neonatal or pediatric intensive care, surgery, dialysis, and endoscopy. A nurse intern is required to receive a total score of at least 60% to pass the evaluation in each area. The hospital assigns a nurse preceptor for each nursing intern. |

Nursing interns demonstrated the confidence, comfort, and perception of readiness for practice. They had some difficulties with managing multiple patients and certain skills, such as how to deal with dying patients and prioritize patient care needs. |

| Sarkoohi et al., 2024 [12] Iran. |

To assess the effect of nursing internship programs on senior undergraduate nursing students’ critical thinking disposition, caring behaviors, and professional commitment. |

Design: Quasi-experimental study with a pretest-posttest, with no control group Setting: A large hospital and a nursing school affiliated with Kerman University of Medical Sciences in the Southeast of Iran Sample: Senior students enrolled in nursing internship programs (n=46). |

the Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CTDI) the Caring Assessment Report Evaluation (Care-Q) the Nursing Professional Commitment Scale (NPCS). |

The internship programs were designed as follows: 1. Nursing principles and skills were taught to the students. 2. All students were required to pass the OSCE before being accepted into the internship programs. 3. The Afzalipour Hospital was selected to implement the internship programs. 4. Students were divided into groups of 3–4 members in the target wards. 5. Several meetings were held with the head of the hospital, nurse managers, supervisors, and head nurses to coordinate programs. 6. The head nurse of each ward supervised the students’ theoretical and practical education. 7. The school of nursing appointed an instructor to supervise clinical education and resolve the educational challenges of the students. 8. The daily lesson plan and practical and instructional tasks were provided to the students. 9. After the programs were completed, the OSCE was conducted. 10. At the beginning, the students, head nurses, and the clinical supervisor of the faculty was given the checklist for the OSCE, and they were all made aware of the training and evaluation process. |

The senior nursing students’ caring behaviors improved, but the total scores of critical thinking disposition and professional commitment did not change significantly after the nursing internship programs. |

| - | - | - | - |

The students took the care responsibility of the patients they care for under the nurse's supervision. Each student kept a record of their care plan and discussed the maintenance plan with the clinic responsible lecturer at least once a week. |

- |

| Ayaz-Alkaya et al., 2018 [15] Turkey. |

To determine the effect of nursing internship program on professional commitment and burnout of senior nursing students. |

Design: Quasi-experimental study with a pretest and posttest without control group Setting: Nursing department in a university Sample: Students attending nursing internship program (N=101). |

The Burnout Measure Short Version (BMS) Nursing Professional Commitment Scale (NPCS). |

1 academic year at fourth year of nursing education program. Nursing internship program consists of two courses: 3 hrs theoretical and 18 hrs practical training per week. Internships in internal medicine, general surgery, gynecology, pediatric, psychiatric and public health clinics. |

After the nursing internship, 77.2% were pleased to study nursing, 83.2% were pleased to be a senior student, 55.4% did not have any intention to change their profession, 81.2% wanted to work as nurses, and 82.2% were planning career advancement in nursing of the students, 34.7% and 43.6% were found to experience burnout, before and after the nursing internship. Nursing professional commitment scale was increased after the internship program. |

| Donmez et al., 2022 [16] Turkey. |

To determine the achievements of nursing students from internship practices. | Design: Descriptive study Setting: Nursing Faculty in western Turkey. Sample: Intern students (N=250). |

The Achievements Gained from Internship Practices Form (AGIP). |

In the final year internship practice, students perform an internship practice in a total of 6 fields; in internal medicine, surgical, women's health, pediatric, mental health, and public health nursing. During internship practice, nursing students are evaluated in terms of the nursing process, psychomotor/ cognitive skill practice, basic nursing knowledge and communication at the end of each rotation. |

The interns considered themselves to be the most sufficient was communication and the field in which they considered themselves to be the most insufficient was the nursing process. Intern students who selected the nursing as first choice and were 21-23 aged got higher scores from the sub-dimensions of practice, basic nursing knowledge and communication. |

| Aboshaiqah et al., 2018 [19] Saudi Arabia. |

- To validate and culturally adapt the Arabic version of the Self-efficacy for Clinical Evaluation Scale (SECS) - To explore nursing interns’ perceived confidence (self-efficacy). |

Design: Cross-sectional Setting: Four public tertiary training hospitals Sample: Nursing students registered in internship program (N=300). |

Self-efficacy for Clinical Evaluation Scale (SECS). |

1-year internship program Four phases of clinical rotations: 2-week orientation, 20-week in medical and surgical units, 20-week rotation in specializations such as critical care and emergency department, and lastly 10-week elective to areas which the interns prefer. The preceptors evaluate and monitor the nursing interns' performance over the 12 month-period. The interns can only perform procedures with the approval and supervision of the preceptors. The preceptors test and facilitate the improvement of interns in theoretical knowledge, skills and attitude towards becoming a competent nurse practitioner. The interns are paid, \and they have to comply with the 12 h shift during working days per month. |

The interns perceived that they achieved confidence in accomplishing the clinical learning objectives. Female interns were more confident and considered clinical learning objectives more important compared to their male counterparts. Confidence or perceived self-efficacy and perceived importance of learning objectives was developed along the course of their internship. |

| Mohammed and Ahmed, 2020 [21] Saudi Arabia. |

To evaluate the nurse interns’ satisfaction towards internship program and their perceptions of hospital educational environment. | Design: Cross-sectional Setting: Albaha University, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, and two hospitals. Sample: Internship nurses from Albaha University (n= 195). |

The postgraduate hospital as an Educational Environment Measure (PHEEM) The satisfactory scale. |

Not reported. | Nurse interns’ reported to be highly satisfied, and their perceptions of role autonomy, teaching, and social support were related to level of satisfaction. |

| Zhao et al., 2024 [22] China. |

To determine the relationship between transition shock with patient safety attitudes, professional identity and climate of caring among nursing interns. |

Design: Cross-sectional Setting: university affiliated hospital in Hunan province Sample: Nursing interns who had completed internship (n=387). |

Transition shock scale for undergraduate nursing students. Patient safety attitudes and professional qualities of trainee nursing students scale. Professional identification scale. Nursing students’ perception of hospital caring environment scale. |

Not reported. | Nursing interns experienced transition shock at a moderate level and the highest levels of transition shock in response to overwhelming practicum workloads, with the second being related to the conflict between theory and practice. Transition shock was negatively correlated with patient safety attitudes, professional identity and climate of caring among nursing interns. |

| Authors, Year [Ref] & Country |

Study Objective (s) | Study Design, Settings & Sample (N) | Data Collection & Analysis | Duration and Description of Internship Program | Key Findings/Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jahromi et al., 2023 [1] Iran. |

To describe and interpret the experiences of nursing students from the internship program. | Design: Interpretive phenomenology study. Setting: 10 universities. Sample: Nursing students in Semester 8, undergoing internship programs (N=12). |

In-depth interviews Van Manen’s three approaches: “holistic approach,” “selection or highlight approach,” and “detailed approach.”. |

Not reported. | The main themes: “professional identity development,” “moving toward professional self-efficacy,” and “developing coping strategies for workplace adversities.” Students had positive experiences, including professional identity development and moving toward professional self-efficacy. Some students faced challenges such as a lack of trust from some nurses and patients or the feeling of being abused. |

| Shahzeydi et al., 2022 [4] Iran. |

To explore nursing faculty, managers, newly graduated nurses, and students’ experiences of nursing internship program implementation. |

Design: Qualitative descriptive. Setting: Faculty and hospitals. Sample: 17 nursing internship students, 12 nursing managers, 3 faculty members, 10 nursing preceptors, and 5 newly graduated nurses from the internship program (N=47). |

In-depth semi-structured interviews. Content analysis. |

Final-year nursing students fulfill their internship program in various hospital wards, including 20 shifts per month, and are paid a monthly salary. The head nurses assign two patients to each student in the first week, three in the second, and four in the third and fourth weeks. Students are independently responsible for patients; however, they work under the nurse’s supervision. |

Five themes: facilitation of socialization process, filling the gap between theory and practice, improving self-confidence and independence, an opportunity for clinical skill training, and ‘Achilles’ heel of the clinical setting. Participants’ experiences revealed that the internship program helped fill the theoretical and practical training gap. Increasing students’ self-confidence was one of the significant features of the internship program. Routine centeredness, imposing more work on students and lack of amenities were identified as challenges. |

| Althaqafi et al., 2019 [8] Saudi Arabia. |

To explore nursing students' clinical practice experiences and challenges during the internship period. | Design: Qualitative descriptive Setting: Faculty of Nursing at one selected university Sample: Bachelor of nursing students in the internship year (n=12). |

Semi-structured focus group Interviews. Thematic analysis. |

One-year internship, after completing three-year baccalaureate programme in nursing science. Internship period is a mandatory requirement of the Saudi Council for Health Specialties in Saudi Arabia. |

Five main factors affecting the nursing interns' clinical practice: the support of the nursing staff, the hospital orientation program, the preceptorship program, educational program, and the responsibility level of the nursing interns. Unfair treatment, the ignorance of healthcare professionals, and being involved in non-nursing work were highlighted as challenging factors for interns’ clinical practice. |

| AlThiga et al., 2017 [9] Saudi Arabia. |

To investigate nursing intern and faculty perceptions toward educational preparation for clinical teaching and development of clinical competencies. |

Design: Mixed methods Setting and Sample: Nursing interns (n=46) and faculty members (n=29) from King Abdul-Aziz University. |

The Clinical Instructional Questionnaire Four open-ended questions. |

1-year internship Clinical settings include pediatric (medical-surgical), adult (medical-surgical), critical care (pediatric-neonatal, adult-medical, adult-surgical), operation room, emergency room, dialysis (hemodialysis, peritoneal), obstetrics, gynecology, labor and delivery, and endoscopy. |

Perception of clinical teaching experiences and the development of clinical competence were positive. Nursing interns rated actual experiences of knowledge base and skills significantly lower than faculty perceptions. A variety of clinical settings, training hospital support for the students, teaching strategies such as nursing care plan, pre and post conference, enhanced learning and teaching. |

| Aghaei et al., 2021 [13] Iran. |

To explain the facilitating and inhibiting factors of nursing students’ adjustment to the internship. | Design: Qualitative Setting: Nursing and Midwifery School affiliated with a large metropolitan medical university in northern Iran. Sample: Final year nursing students in seventh and eighth semester, undergoing internship (N=17). |

Semi-structured interviews. Content analysis. |

21-credit course, equivalent to 1121 hours, rotation in the morning, evening, and night shifts in various wards. | Support systems, the internship structure and setting, and personal and professional factors were identified as facilitators and barriers of adjustment to the internship. Strong support systems led to a better adjustment, whereas poor support systems negatively affected students’ adjustment. Inadequate planning and organization of the internship program and the poor structure of human resources, such as high workload and lack of ward facilities, were identified as barriers to adjustment. Personal and professional factors such as poor self-efficacy, physical and mental tensions are barriers to adjustment. |

| Ahmadi et al., 2020 [14] Iran. |

To explore the challenges related to the internship education of nursing students. |

Design: Qualitative Setting: Educational hospitals affiliated with Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (KUMS) Sample: eight nursing students who had at least one semester of experience in internship (N=8). |

Semi-structured interviews. Three-stage content analysis approach. |

Duration is not clearly reported. The internship program planned for nursing students, in connection with several Iranian universities, was com- menced in Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences as a pilot plan (less than two years). At the initial stage, the students spend three days at an orientation workshop and received a booklet guide, then they are introduced to the education center of the hospital. The students are then referred to designated wards and work under the supervision of an expert nurse, head nurse, and supervisor (a faculty member). |

Seven categories emerged from data analysis: education before internship, lack of support, planning difficulties, interaction with staff, invisible evaluation, welfare defects, and professional identity. Nursing students highlighted some challenges including lack of amenities and a support system, interaction difficulties with staff, ambiguity in the evaluation system, and obscurity in identity. |

| - | - | - | - | - | The pressure of the initial stage was operational pressure (80.0%), intermediate stage was nurse–patient communication (50.0%), and last stage was employment pressure (70.6%). Nursing students mainly expected to improve their operational and communication skills, and to acquire clinical experience, thinking ability and frontier knowledge. |

| Xiong and Zhu 2022 [17] China. |

To identify psychological experience at different internship stages among internship nurses. | Design: Qualitative Setting: Hospital Sample: Internship nurses (N=48). |

In-depth semi-structured interview Mixed data analysis strategies. |

The internship duration is 9–12 months. Other information about internship is not provided. |

The nursing students experienced various degrees of trepidation and confusion during internship, especially in the early stage, which mainly came from the new environment, new teaching methods, unskilled operations, facing various interpersonal relationships and fear of errors or accidents. . |

| Alruwaili et al., 2024 [18] Saudi Arabia. |

To assess the readiness levels of intern nursing students and investigate the factors affecting their transition to professional practice within the Al Jouf region in Saudi Arabia. |

Design: Mixed methods Setting and Sample: Nursing interns who had fulfilled a minimum of three months in internship program within the Al Jouf region (N=135). |

Nursing Practice Readiness Scale (NPRS). Two open-ended questions, using content analysis. |

1-year internship Detail information about internship program is not provided in the study. |

Most intern nursing students (63.7%) exhibited a moderate level of readiness. 70.4% and 55.6% of the students showed moderate readiness in terms of their professional attitudes and patient-centeredness. One-third of the students demonstrated a high level of readiness in the self-regulation domain (36.3%), and collaborative interpersonal relationships (33.3%). The most common barriers were stress and uncooperative nursing staff. The most common facilitating factors were availability of clinical instructors from nursing faculty, clear directions, and support from hospital staff. |

| Aboshaiqaha and Qasim, 2018 [20] Saudi Arabia. |

To explore nursing interns' perceptions towards the development of clinical competence during preceptorship. |

Design: Mixed methods Setting: A tertiary hospital in Riyadh Sample: Undergraduate nursing interns (n=92). |

Perceived effectiveness of preceptorship using the Clinical Competence Questionnaire (CCQ). Two open-ended questions, using thematic analysis. |

1-year internship, using preceptorship model, i.e., nursing interns are supervised by clinically trained preceptors. | Most of the nursing interns perceived preceptorship as a positive experience. The preceptorship program enhanced the competencies in the clinical setting. The availability, approachable attitude, and trustworthiness of the preceptor were viewed as influential factors in improving the interns' clinical competence. . |

| Bahari et al., 2021 [23] Saudi Arabia. |

To identify students’ perspectives on the facilitators of and barriers to success in clinical internships in public and private hospitals. |

Design: Qualitative descriptive Setting: Public and private nursing colleges with internships in both public and private hospitals. Sample: 16 nursing students (during internship) and 4 faculty members (N=20). |

Virtual semi-structured interviews. Thematic analysis. |

12-month program Other information about internship is not provided. |

Facilitators of success included the program curriculum, hospital internship program, and contribution to the nursing board exam. Barriers to success were exploitation, lack of self-confidence, lack of incentives, and the long duration of the programs. |

| Alanazi et al., 2023 [24] Saudi Arabia. |

To explore the experiences of internship students and address the. | Design: Qualitative naturistic descriptive Setting: Four government hospitals in the northern and middle regions of Saudi Arabia. Sample: Internship students having at least three months or more of internship experience (n=20). |

Focus group discussion using semi-structured questions, and observation documented daily in reflective journals. Content analysis. |

Internship year is a mandatory in final year of the bachelor’s degree program. Clinical rotations in medical, surgical, pediatric and maternity units. Responsibilities of interns include assisting with patient assessments, administering medications, providing wound care, and offering emotional support to patients and families. |

Four major themes were generated: 1) Transferring shock, 2) Self-learning, 3) Supportive environments, and 4) Factors facilitating learning. Transferring shock comprised two subthemes: feeling lost and feeling left out. The factors influencing internship experiences are support, guidance, workload, and communication. |

| Alharbi and Alhosis 2019 [25] Saudi Arabia. |

To explore the challenges and difficulties encountered during nursing internship. |

Design: Qualitative descriptive. Setting: Colleges of nursing in the qassim region Sample: Nursing interns (n=17). |

Face-to-face semi-structured interview. Thematic content analysis. |

1-year intensive clinical practicum, after graduation to be eligible to register and take the board examination by the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties. | The nursing interns experienced inappropriate treatment from the clinical staffs through lack of communication, disregard, and exploitation from the staffs. They perceived feeling lost due to the identified gap in the organizational structure in the training department of some hospitals, lack in regular follow-ups from the college, and lack of willingness to teach from the clinical preceptors. |

In Iran, the internship program was designed in the final year of the Bachelor of Nursing program; however, the length of the internship was not clearly stated [4, 12]. One study stated that the internship program comprised 21 credits, equivalent to 1121 hours, with rotating shifts in various wards [13]. Students performed patient care independently but under the nurse’s supervision, and the faculty visited students at least four times a month, evaluating their performance and providing feedback [4]. As indicated by Ahmadi et al. [14], the students underwent a three-day orientation workshop at the initial stage, and then they worked under supervision.

As reported in a recent study in Iran, the design of internship program involved several components: i) teaching nursing principles and skills, ii) assessment through objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) before the students were accepted into the internship program, ii) selecting a hospital for the implementation of the internship program, iv) dividing students into groups of 3–4 in each ward, v) meetings with the head of the hospital, nurse managers, and supervisors to coordinate the implementation of the programs, vi) supervision of the students by the head nurse, vii) appointment of instructor to supervise clinical education, viii) providing daily lesson plans and instructional tasks to the students, ix) conducting OSCE after completion of the internship, and x) providing OSCE checklist to students and supervisors [12].

In Turkey, the nursing internship was 1-year program undertaken in the fourth year of the nursing program, which comprised two courses: a 3-hour theory session and 18-hours practical training per week [15]. Students performed an internship practice in medical, surgical, pediatric, gynecology, psychiatry, and public health settings [15, 16]. The students performed the patient’s care under supervision, having a record of the care plan, which is to be discussed with the lecturer once a week [15].

In China, as indicated in one study, the internship duration was 9–12 months; nonetheless, other information about internships is not provided by Xiong and Zhu [17]. The other study conducted in China reported that the undergraduate nursing program included 1-year internship after completing 3 years of basic nursing and medicine [3]. The internship program comprised preparation and internship sections. The preparation section involved i) hospital assignment, in which students were assigned to the affiliated hospitals, ii) pre-internship training, a 2-week course designed to strengthen clinical skills, and iii) mobilization meeting, providing detailed information and regulation of internship. Succeeding the preparation section, the internship section involved selecting and training preceptors, preceptorship, post-preceptorship examination, providing monthly feedback, mid-term nursing rounds, and a summary meeting [3].

3.3. Outcomes of the Pre-registration Nursing Internship Programs

Reportedly, there were two quasi-experimental studies [12, 15] and one longitudinal study [3] that measured the outcomes of the nursing internship program. The outcome measures were varied in three studies: professional commitment was measured in two studies, caring behaviour/ability was measured in two studies, burnout was measured in one study, and critical thinking disposition in one study.

In Tukey, one study investigated the outcomes of a nursing internship program on professional commitment and burnout using a quasi-experimental design without including a comparison group [15]. The study participants were students attending a nursing internship program (n=101). The result indicated that, after completing the nursing internship, 77.2% of internship students were satisfied to study nursing, 55.4% had no intention to change their profession, 81.2% were keen to work as nurses, and 82.2% were planning for their career advancement in nursing. The encouraging result showed that the level of nursing professional commitment was increased after the internship program. However, internship students did experience burnout before and after the nursing internship, 34.7% and 43.6%, with a higher level of burnout after the internship.

In an Iranian study, a quasi-experimental study without a comparison group was conducted to determine the effects of internship programs on critical thinking, professional commitment, and caring behaviors among senior students enrolled in nursing internship programs (n=46) [12]. The results indicated that students’ caring behaviors significantly improved. However, their critical thinking and professional commitment did not change after the completion of the internship. In China, a descriptive longitudinal study examined nursing students’ caring ability before and at the end of the internship (n-305) [3]. The result indicated that the overall caring ability, the cognitive domain, and the patience domain increased after the internship compared to the scores measured before the internship.

In summary of the results pertaining to the outcomes of nursing internship programs, students’ caring ability and behaviours were found to improve in two studies [3, 12]. The outcomes of nursing internships on professional commitments indicated inconsistent results; one study indicated an improvement in professional commitment after internship [15], whereas the latter study indicated no significant improvement in professional commitment [12]. Interestingly, their critical thinking disposition did not improve after completing the internship program.

3.4. Perceptions of the Internship Programs

Amongst the reviewed studies, eleven studies investigated nursing interns’ perceptions of the internship program in various aspects: clinical preparation and readiness, perceived clinical competency, clinical learning environment and supervision, perceived self-efficacy, transition shock, and achievement gained from the internship program.

Almadani et al. [10] conducted a study in Saudi Arabia, investigating nurse interns’ perceived readiness and clinical preparation for practice (n=130). The results indicated a moderate level of readiness and clinical preparation. An earlier study in Saudi Arabia, evaluating the perceived level of preparation in the internship program (n=121), indicated that most of the nurse interns rated the highest percentage for educational preparation requirements in teaching and providing information, psychomotor skills, and communication skills [2]. Another study by Alruwaili et al. [18] investigated nursing practice readiness among nursing interns (n=135) and indicated that most interns (63.7%) had a moderate level of readiness, in which 70.4% and 55.6% had moderate readiness in professional attitudes and patient-centeredness, respectively. Another study in Saudi Arabia examining the perceived readiness of intern nurses (n=44) demonstrated confidence, comfort, and perception of readiness for practice [11].

A study in Saudi Arabia compared the perceived level of clinical competency among two groups of nursing students (n=244) enrolling in the last period of the fourth year and the last three months of internship [6]. The results showed that students in the internship year exhibited a higher level of clinical competency than those students in the fourth year, suggesting that clinical practice during the internship period contributes to the development of clinical competencies. In a study evaluating the perceived self-efficacy of nursing interns (n=300) in Saudi Arabia, the interns responded that they had developed confidence and self-efficacy in achieving learning objectives [19].

AlThiga et al. [9] conducted a mixed methods study in Saudi Arabia to investigate the perceptions of nursing interns (n=46) and faculty (n=29) on educational preparation for clinical competencies. Data were collected using the Clinical Instructional Questionnaire and four open-ended questions. The results indicated positive clinical experience and the development of competencies rated by nurse interns; however, nursing interns rated lower than those rated by faculty members, pertaining to the actual experiences of knowledge and skills. Students' learning experiences were found to be enriched through exposure to various clinical areas, hospital support, teaching strategies aligned with nursing care plans, and the facilitation of pre- and post-conferences. A similar study was conducted in Saudi Arabia that explored perceptions of nursing interns on the development of clinical competency during preceptorship (n=92) using a mixed methods design [20]. In the results, most of the interns remarked preceptorship as a positive experience, enhancing their clinical competencies. The availability, approachability, and reliability of the preceptors were reported as influencing factors for the improvement of clinical competency.

Another study in Saudi Arabia investigated nursing internship students’ (n=250) perception of their clinical learning environment and supervision (CLES) [7]. The results indicated positive perceptions, with the sub-dimension regarding the nurse educator’s role was scored higher than other subdimensions. There was a weak positive correlation between the perception of CLES and the grade point average (GPA); those obtaining higher GPAs were likely to have a positive perception of their CLES. Similarly, a study in Saudi Arabia examined the nurse interns’ satisfaction with the internship program and their perceptions of the hospital educational environment (n=195). The result indicated that nurse interns’ perception of role autonomy, teaching strategies, and social support were related to their level of satisfaction, suggesting that the hospital learning environment is an important determinant of the success of internship programs [21].

One study in China investigated the relationship between transition shock with patient safety attitudes, climate of caring, and professional identity among nursing interns (n=378) [22]. The result indicated that nursing interns experienced a moderate level of transition shock, with the highest levels of transition shock in dealing with substantial workloads, and the second highest level of transition shock was related to theory and practice gaps. Notably, transition shock was found to be negatively correlated with patient safety attitudes, climate of caring, and professional identity. In Turkey, Donmez et al. [16] conducted a study to evaluate the achievements of internship practices (n=250). The interns considered themselves to be the most sufficient in communication and practice during the internship.

In summary of perceptions of the internship programs, perceived level of competency and self-efficacy were likely to be improved after completing the internship, demonstrating moderate to high level of preparedness and readiness to practice as professional nurses. A positive perception of the clinical learning experience could enhance academic achievement.

3.5. Experience and Challenges of the Nursing Internship Program

Nine studies included in this review explored the experience and challenges of the nursing internship program. An Iranian study explored the experiences of nursing internship programs from the perspectives of nursing academics, nurse managers, fresh graduate nurses, and students in their internship period (n=47) [4]. The participants responded that the internship experience helped them fill the gap between theory and practice, improving their self-confidence and independence. However, some challenges were identified, including routine centeredness, imposing more work on students, and lack of amenities. Jahromi et al. [1] conducted an interpretive phenomenology study in Iran to understand the experiences of nursing students undergoing internship programs (n=12). The findings revealed positive experiences of nursing internships, developing professional identity, increasing self-efficacy, and developing coping skills in dealing with workplace adversities. On the other hand, some students encountered challenges, such as a lack of trust and being abused.

A study conducted by Aghaei et al. [13] in Iran explored facilitators and barriers to nursing students’ adjustment to the internship (n=17). The findings revealed that an effective support system facilitated a better adjustment, whereas a poor support system impeded students’ adjustment. The poorly organised internship program, high workload, and inadequate facilities were identified as barriers to adjustment. A similar study in Iran explored the challenges related to nursing internships (n=8) [14]. The findings indicated some challenges, including a lack of facilities, an inadequate support system, difficulties in interaction with staff, and an ambiguous evaluation system.

In Saudi Arabia, Bahari et al. [23] conducted a qualitative study to identify the enablers and barriers to success in internship from the perspective of students (n=16) and faculty (n=4). The study findings revealed that the facilitators of success included the program curriculum, hospital internship program, and contribution to the nursing board exam. In contrast, the barriers to success were exploitation from some of the preceptors, lack of self-confidence, low incentives, and the long internship duration. The majority of the students who participated in the study expressed that a 12-month internship is too long and could be exhausting. Alanazi et al. [24] explored the experiences of internship students in Saudi Arabia (n=20). The identified factors influencing internship experiences were support, guidance, workload, and communication. The interns experienced transferring shock, leading them to feel lost and left out.

Althaqafi et al. [8] explored nursing students' experiences and challenges during internships in Saudi Arabia (n=12). The findings revealed the factors affecting the nursing interns' clinical practice, which included the support of the nursing staff, the orientation program, the preceptorship, and the level of responsibility for nursing interns. Moreover, the nursing interns reported challenging factors, such as unfair treatment, being ignored, and getting involved in non-nursing work. Alharbi and Alhosis [25] conducted a similar qualitative study that explored the challenges encountered during a nursing internship (n=17) in Saudi Arabia. As reported in the findings, the nursing interns encountered challenges with faulty treatment from the clinical staff.

In China, a qualitative study by Xiong and Zhu explored the psychological experience of student interns in different stages of internship (n=48) using in-depth semi-structured interviews [17]. The findings revealed that nursing students encountered certain degrees of anxiety and confusion during the internship, especially in the early stage, due to the new environment, lack of clinical skill, intricate interpersonal relationships, and fear of medical errors. In the early stage, the primary source of pressure was operational pressure (80.0%). In the intermediate stage, it was related to the nurse-patient relationship (50.0%), while in the final stage, the pressure was associated with employment (70.6%). Nursing students asserted their expectation to enhance operational and communication skills and to acquire clinical experience and thinking ability.

In summary, nursing interns had both positive and negative experiences of undergoing internship programs. The main factors influencing internship experiences were the structure of the program, support system, guidance, workload, and communication. Positive aspects of a nursing internship included filling the theory and practice gap and improving self-confidence, independence, and readiness for practice. Common challenges encountered were insufficient support, lack of amenities, being exploited and given more workload on interns, being involved in non-nursing work, and facing problems with communication and interpersonal relationships. Other challenges included anxiety and confusion, low incentives, and the long internship duration. All these challenges are noteworthy for further improvement of the nursing internship experience.

4. DISCUSSION

The reviewed studies on nursing internship programs across various countries highlight a diverse yet consistently structured approach to preparing nursing students for professional practice. In Saudi Arabia, the 12-month mandatory nursing internship provides hands-on experience in diverse clinical settings to prepare graduates for the nursing registration exam, requiring a minimum evaluation score of 60% to ensure essential nursing skills and high competency standards. Similarly, in Iran, the nursing internship, integrated into the final year of the Bachelor of Nursing program, comprises 21 credits and 1,121 clinical practice hours, emphasizing supervised care, regular evaluations, OSCE, and group rotations to foster a holistic learning experience. The nursing internship lasts a year, integrating theoretical instruction with 18 hours of weekly clinical practice across specialties. This approach enhances technical skills while emphasizing holistic patient care through regular evaluations and feedback from instructors. Finally, in China, nursing internships last 9 to 12 months following three years of foundational education. This program comprises both preparation and internship phases, employing a preceptorship model in which trained preceptors provide mentorship, guidance, and evaluations to foster continuous competency development. Collectively, these initiatives exemplify a global effort to integrate theoretical knowledge with practical experience, aiming to cultivate well-rounded nursing professionals.

The outcomes of pre-registration nursing internships, evaluated through quasi-experimental and longitudinal studies, provide valuable insights into professional commitment, caring behavior, burnout, and critical thinking, identifying both strengths and areas for improvement. Professional commitment is a vital aspect of nursing internships, as it reflects students' dedication to their future careers. For instance, a Turkish study reported that 81.2% of students indicated a desire to work as nurses after their internships, suggesting that these experiences positively influence their professional identity. However, contrasting findings from an Iranian study revealed no significant changes in professional commitment, highlighting potential differences in the environmental and cultural contexts of the internship programs. In terms of caring behavior, both Iranian and Chinese studies indicated significant improvements following the internships. The hands-on, patient-centered experiences provided in these programs appear to enhance students’ abilities to deliver compassionate care, fostering the empathetic interactions essential for effective nurse-patient relationships. Burnout among nursing students is an escalating concern due to the demands of clinical practice. The Turkish study noted an increase in burnout rates before and after the internship, highlighting the need for improved support systems, including stress management and mental health resources. Critical thinking is essential for quality nursing care, yet evidence indicates limited improvement through internships. The Iranian study by Sarkoohi et al. [12] found no significant gains, suggesting internships may not sufficiently challenge students. Incorporating structured reflective practices and problem-solving exercises could enhance critical thinking skills in future nursing professionals [26, 27].

Perceptions of nursing internship programs are essential for understanding students’ evaluations of clinical preparation, competency development, supervision, and the challenges of transition. Clinical preparation is vital as it fosters practical skills and confidence in students. Research from Saudi Arabia indicates that while interns exhibit moderate clinical readiness, there is a significant need for enhanced training programs to effectively bridge the gap between academic learning and the complexities of real-world healthcare. Perceived clinical competency is another key outcome, reflecting students' ability to apply theoretical knowledge in patient care. Interns reported significant increases in their perceived competencies and self-efficacy following internships, highlighting the importance of hands-on experience in developing confidence and decision-making skills.

Studies from Saudi Arabia emphasized that a supportive environment, combined with effective preceptorship, enhances students’ perceptions and overall academic performance, underscoring the need for strong relationships with nurse educators and preceptors. Transition shock, however, poses a considerable challenge, as noted by Zhao et al. [22], with interns experiencing moderate shock from overwhelming workloads, impacting their professional identity and attitudes toward patient safety. Improved orientation, mentorship, and reflective practices are essential for facilitating smoother transitions. Additionally, research by Donmez et al. [16] found that nursing interns reported significant improvements in communication and practical skills. This finding suggests the ongoing enhancements in internship programs to better prepare students for professional practice and career development [28].

Research on nursing interns' experiences during clinical internships highlights their role in developing professional competencies and identity while also revealing significant challenges affecting learning and well-being. For instance, Shahzeydi et al. [4] highlighted that internships in Iran play a crucial role in fostering independence and confidence by facilitating students to apply their knowledge in real-world situations. Similarly, Jahromi et al. [1] observed enhancements in students' professional identity and self-efficacy, which helped them develop effective coping strategies for workplace challenges. In Saudi Arabia, studies by Bahari et al. [23] and Althaqafi et al. [8] highlighted the importance of structured curricula and preceptorships in enriching learning experiences and adequately preparing students for their nursing board exams. Meanwhile, Xiong and Zhu [17] noted that initial feelings of anxiety among students in China gradually transformed into a proactive approach toward skill enhancement, demonstrating the transformative potential of internships in shaping competent nursing professionals.

While nursing internships offer numerous benefits, students frequently face substantial challenges that impede their learning and adjustment. Research in Iran by Aghaei et al. [13] and Ahmadi et al. [14] highlighted problems, such as high workloads, inadequate support, and poorly organized programs. Likewise, interns in Saudi Arabia experienced transition shock and a lack of guidance, while Xiong and Zhu [17] noted various challenges throughout the internship, including operational pressure and communication difficulties. These issues can negatively impact students’ experiences and their views of the nursing profession. Therefore, nursing faculty and affiliated hospitals need to develop support strategies to overcome such challenges and enhance the internship experience [29-31].

4.1. Strength and Limitations

This scoping review provides a comprehensive mapping of the evidence on nursing internships in pre-registration nursing education programs. A key strength of this review is its inclusive approach, incorporating a diverse range of studies, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods designs, to ensure a broad understanding of the topic. However, this review has some limitations. As a scoping review, the quality of the selected studies was not assessed [32], and there was significant variation in the methods and variables examined across the studies. Additionally, the review was limited to studies published in English, excluding non-English publications that may offer valuable insights. As a result, the findings may have limited applicability to diverse populations.

4.2. Implications to Nursing Education and Practice

The reviewed studies highlight important implications for nursing education and practice, underscoring the need for enhanced preparation of students for professional roles. Nursing education programs should adopt structured internship curricula that integrate theoretical knowledge with diverse clinical experiences, addressing gaps in clinical preparation, competency development, and the transition to professional practice. These programs should also foster professional commitment by cultivating positive nursing identities through mentorship, role modelling, and reflective practices, ensuring students are engaged and prepared for long-term career success.

Compassionate, patient-centred care should be a central focus of nursing internships, with strategies to nurture empathy through reflective practices, interpersonal skill-building, and meaningful patient interactions. To mitigate burnout, programs must incorporate stress management resources, mental health support, and wellness initiatives. Enhancing critical thinking through case-based problem-solving, reflective practices, and opportunities for independent decision-making is essential to connect the clinical tasks and higher-order cognitive skills that are critical for quality care.

A supportive clinical learning environment and effective preceptorship are vital for fostering professional growth and competency development. Training preceptors and educators to provide meaningful guidance and feedback is essential. Programs should address transition shock by offering comprehensive orientation, continuous mentorship, and opportunities for reflective discussions to ease students into clinical roles. Additionally, operational challenges, such as high workloads and disorganized programs, should be addressed with standardized frameworks and improved communication systems to enhance the overall internship experience.

CONCLUSION

The nursing internship programs effectively bridge theoretical knowledge with practical skills, fostering professional growth, clinical competency, and communication abilities. While these programs enhance professional commitment, caring behavior, and patient-centred care, challenges, such as burnout, transition shock, and limited critical thinking development, highlight the need for targeted improvements in support systems and curriculum design. Addressing issues like anxiety, supervision quality, and structured mentorship is essential to optimize learning, well-being, and readiness for professional practice. By tackling these challenges, nursing internships can better prepare nursing students for the demands of their profession while fostering a positive perception of nursing.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: C.L.: Data analysis and interpretation of results; N.T.T.H: Draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| CCQ | = Clinical Competence Questionnaire |

| SCFHS | = Saudi Commission for Health Specialties |

| NT | = Nurse Educator |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.