All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Psychiatric Care Setting from the Perspective of Psychiatric Nursing Managers

Abstract

Background

Nursing managers are well-positioned to enhance holistic care for patients in psychiatric settings. Managers need to use evidence-based data available to them when making nurse staffing decisions. Patient classification systems can be an excellent source of patients’ priority care needs.

Objective

To understand the meaning of using patient classification systems as a management tool for psychiatric nursing managers.

Methods

Qualitative study with a content analysis methodological framework. Ten nursing managers from psychiatric institutions in the state of São Paulo participated. Data were collected between August 2016 and May 2017 using a semi-structured interview with recorded audio.

Results

The sample consisted of nine women and one man with an average of 14 years’ experience in mental health and seven years of management experience. The psychiatric care setting emerged as a general theme surrounded by four subthemes: current model of decision making, ideal model of decision making, nursing staff dimensioning/staffing, and professional and mental health legislation. Only half of the managers used a patient classification system as a management tool, and there were difficulties associated with their use of the tool.

Conclusion

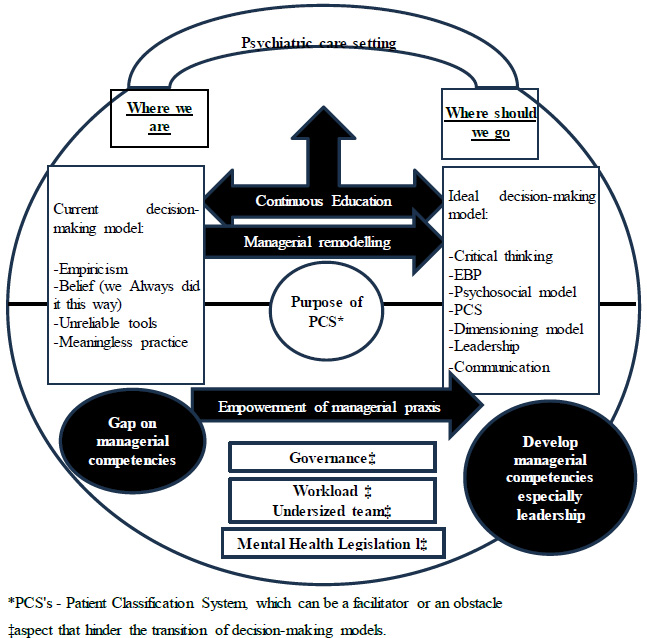

A conceptual model was developed based on the themes, subthemes, categories, and sub-categories in this study. The model demonstrates major differences between psychiatric settings with biomedical models versus psychosocial models. Managers with knowledge of PCS data can better advocate for patients’ holistic needs and adequate nursing resource allocation. Managers may lack the knowledge and skills required for model transformation, and continuing management/leadership education is recommended.

1. INTRODUCTION

Mental health in Brazil has undergone political remodelling since 2001, with the enactment of a law providing for the protection and rights of people with mental disorders and remodelling of psychiatric care with the progressive extinction of asylums. Known as the Brazilian Psychiatric Reform Law, this law aims to change the public and professional stereotypes about individuals with mental disorders. The law includes a redefinition of mental disorders and the establishment of holistic care practices for individuals with psychiatric diagnoses. However, change requires not only reform but also a psychosocial model to expand the clinical practice to include the physical, mental/psychological, and social needs of individual clients. According to the psychosocial model, every individual has unique interactions with the natural and social environment, and every individual’s well-being is a subjective experience that needs to consider their specific physical, mental and social needs [1-4].Shifts towards more holistic care practices are also supported by public policies that endorse the formation of psychosocial care centres that are intended to substitute for psychiatric hospital beds (Redes de Atenção Psicossocial - RAPS).The number of psychosocial care centres (Centros de Atenção Psicossocial - CAPS) has increased from 424 to 1937, a transition that, in the legal-political dimension, has been supported by ordinances enabling deinstitutionalization and reform of the hospital system with respect to psychiatric care [5-9]. The other three dimensions of psychiatric reform have included: 1) the theoretical-care dimension, which considers individuals’ multidimensionality and care needs (versus the disease-curative approach); 2) the technical-care dimension, which represents the network of services required in psychosocial care centres (e.g., reception, admissions and intervention spaces)treatment spaces); and 3) the sociocultural dimension, which addresses staff-patient interactions, including patient-centred care, where the individual is a “co-manager” if their treatment plan [2, 3, 10].

Nursing is integral to all three dimensions through the Professional Exercise Law, which acknowledges nursing’s participation as an equal team member on psychiatric teams [11-13].

Before the transition to the psychosocial model, nurses and other healthcare practitioners functioned according to the biomedical model. The biomedical model considers the human body as a machine with parts; disease is seen as a malfunction of biological mechanisms, which are studied from the point of view of cellular and molecular biology, and the role of practitioners is to intervene, physically or chemically, to fix the malfunctioning mechanism [14, 15]. The transition of the models has been slowed by the complexity of the psychosocial model’s three dimensions and holdovers of the biomedical model, especially in acute care services in hospitals [16]. A starting point for model reform, therefore, has been the hospital setting, where early diagnosis and treatment take place for individuals with acute psychiatric episodes [17]. At hospitalisation, the admission process and psychiatric interventions have been changing to consider the holistic needs of patients in the hospital and at discharge to the community—to ensure a comprehensive treatment plan and smooth transitions from the hospital to community-based care. Nurses play a key role in case discussions with patients and teams in the hospital and with patients’ territories at discharge [18]. An earlier evaluation of Brazilian psychiatric institutions in 2011 revealed that about 50% of 189 psychiatric institutions were still functioning according to the biomedical model. From a nursing perspective, staffing inadequacies and lack of effective nursing management were associated with the absence of patient-centred care planning and discharge planning. For example, 75% of nursing documentation in the medical records focused on the physical diagnosis [19]. Structurally-technically, there was an insufficient allocation of nursing staff based on individual patients’ physical-mental-social needs [20].

Research has been lacking on evidence-based nursing management and how nurse managers can contribute to psychosocial model implementation [21]. Patient classification systems (PCS) are one management tool comprised of structure, process, and result indicators. They identify the need for nursing care for each patient and inform managers’ workload decisions about the types of nurses (e.g., certification, experience) who should be assigned to specific patients based on patients’ priority care needs. Daily PCS data provide a basis for decision-making at various hierarchical levels of the institution, in addition to directing nursing care. They are also considered an exclusive communication tool for nursing, and they promote nurse manager-nurse empowerment by increasing patient care discussions and decisions among them [22, 23]. Patient classification systems, therefore, increase the possibility of psychiatric setting reform from a biomedical approach to a psychosocial approach to patient care management and delivery. In studies where nurses used PCS, nursing managers stated that PCS provided an objective way of communicating about patient needs and objective data assisted them with determining nursing assignments based on patients’ holistic needs. In addition, managers were better able to determine their staffing and resource allocation needs, including more accurate budget determinations [22, 23].

This current study contributes to nurses’ use of PCS by exploring a Brazilian PCS for psychiatric patients known as the Martins instrument. There is a dearth of research on the use of the Martins instrument in psychiatric care compared to other specialties [24-32]. Moreover, to properly transform nursing management and nurse care in Brazilian psychiatric settings from the biomedical to the psychosocial model, we need to better understand how tools, such as the Martins PCS, can be utilized in model reform.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

This research project was approved by the relevant research ethics committee under protocol number CAAE: 56156616500005411 and protocol 1.657.831, meeting the criteria of the National Health Council [33]. This is a qualitative descriptive study conducted with hospital nursing managers who care for patients with acute mental disorders in the State of São Paulo. Acute care facilities had three administrative profiles: A, General Public Hospitals with psychiatric beds; B, Specialised Psychiatric Public Hospitals; and C, Specialised Psychiatric Hospitals complementary to the Brazilian Health System (SUS). The inclusion criteria required participants to be either a nurse or a psychiatric nursing manager. Data were collected by the principal investigator from August 2016 to March 2017 through semi-structured interviews with recorded audio lasting 30 to 40 minutes in a private room chosen by the manager of the respective institution. The managers were previously contacted by phone, and the meeting was scheduled by email. There was no withdrawal of any participants.

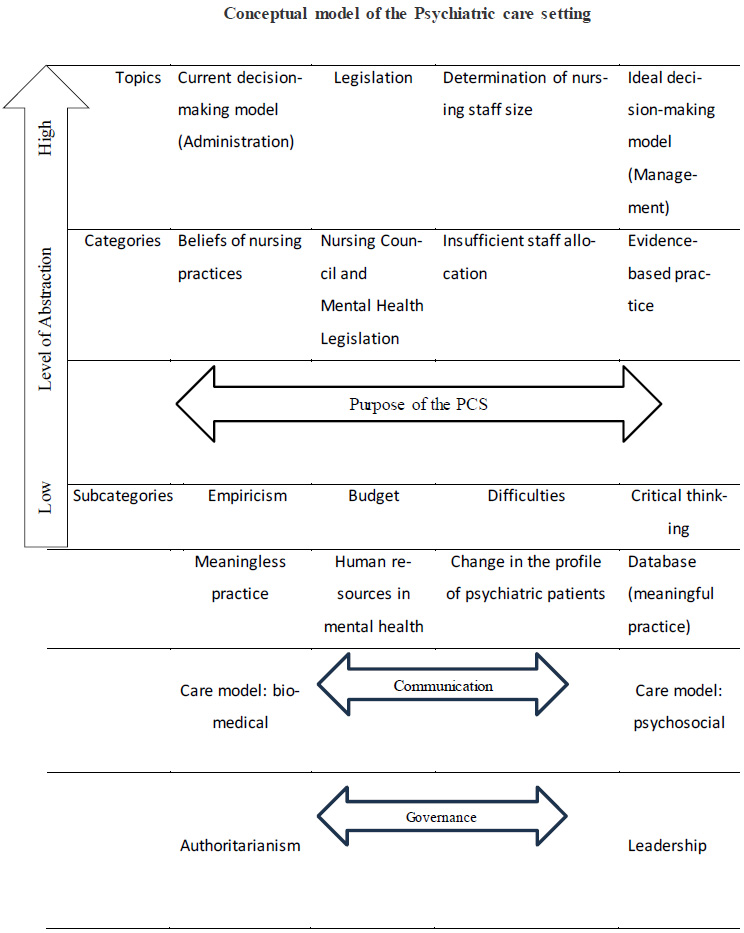

The guiding question was, ‘What does it mean for you to adopt a patient classification system as a management tool?’, followed by complementary questions. The managers were coded by the administrative profile of the institution to which they belonged, followed by the order of interview transcription. Transcriptions took place as soon as possible after each interview. The methodological framework for data analysis was content Analysis based on the Grandhein & Lundman technique [34]. This technique allows for the extraction of manifest and latent discourse content according to the depth and level of abstraction that the researcher seeks. The units of analysis consist of the direct discourse that is selected to be analysed. Direct discourse generates units of condensed meaning or codes. Codes with common content comprise categories. Categories are combined to create themes that are the expression of latent content because they cross the discourses and can generate a comprehensive theme understood as the maximum level of abstraction [34]. N-Vivo12 software was used for categorisation [35]. Based on content analysis, the main theme was the Psychiatric care setting. Subthemes with their respective categories and subcategories were: a) (subtheme) current model of administrative decision-making, (category) beliefs of nursing practice, (subcategories) empiricism, meaningless practice, biomedical care model, and authoritarianism; b) (subtheme) legislation, (category) nursing council and mental health legislation, (subcategories) budget and human resources in mental health; c) (subtheme) determination of nursing staff size, (category) insufficient staff allocation, (subcategories) difficulties, change in the profile of psychiatric patients; (subtheme)) ideal managerial decision-making model, (category) evidence-based practice, (subcategories) critical thinking, database to support meaningful practice, psychosocial care model, and leadership.

In this article, Artificial Intelligence (AI) was used to translate the article from Portuguese into English, firstly by Deeply Translate, with checks by Open Write in full. After that, a native speaker revised the manuscript.

3. RESULTS

Ten nursing managers from the psychiatric unit were interviewed, including nine women and one man, with an average age of 47.5 years. Participants had, on average, 23.1 years since completing their undergraduate nursing degree, 14.2 years of experience in psychiatry, and seven years of managerial experience at their current institution. The levels of education were as follows: two participants held a master's degree in mental health, one had a master's degree in clinical settings, three had a specialization certificate in mental health, two had a specialization in hospital administration, and two had no graduate education.

In general, six managers (A1, A4, B5, B8, C9, C10) used a PCS for nursing staff assignments. Four managers, A4, B5, B8 and C9, used the Martins instrument, while A1 and C10 used an administrative tool to make assignments. A4, B5, and B8 performed daily patient classifications using the Martins instrument, while other managers did annual classification reviews as required by the Federal Nursing Council (Conselho Federal de Enfermagem - COFEN). A1, A2, and A4 used online databases associated with their institutions’ electronic medical records; and B5, B6, and C10 maintained PCS data on Excel spreadsheets. Those who used an administrative instrument had challenges capturing nursing care needs for psychiatric patients. Managers using the Martins instrument said that despite adaptations of the instrument for psychiatric use, there were challenges for using it to staff for this population. Anecdotally, A2 used the Martins instrument as a care tool to identify 30% of the most complex patients and to develop individual nursing care plans for more complex patients.

Managers were questioned about the use of their PCS for hiring nursing staff. No staffing governance in institutions A and B was reported; C10 stated that they used their administrative data to advocate for more staff; and C9 stated that their institution follows an ordinance from the Ministry of Health to decide the number of nurses needed hospital-wide. Every manager stated that they employed assistance from The Regional Nursing Council of the State of São Paulo (Coren-SP), which offers technical support (e.g., staffing, budget) to managers.

The topic ‘Psychiatric Care Setting’ and its respective categories and subcategories are shown in Fig. (1). The content was extracted from the lowest level of abstraction (manifested content) to the highest level of abstraction (latent content).

A conceptual model (Fig. 1) of the psychiatric care setting depicts the current model of decision-making on the left-hand side of the figure, and the ideal model of decision-making is on the right: The statements of managers reveal: We base our decisions on our experience, and it has always worked (B7). There was no parameter, I mainly based it on the experience I had in the other psychiatric ward (A2). When I determined the nursing staff complement for the first time, I used a clinical instrument that was not ideal, but I managed to prove to the board the need to hire more nurses (C10). Here, we used Martins' instrument 6 years ago, and we annually review nursing staff dimensioning (staffing needs, and all data are in a spreadsheet in Excel (B8).

Understanding of nurses who manage a psychiatric setting about the use of Patient Classification Systems as a management tool. Botucatu, SP, Brazil, 2017.

The Regional Nursing Council of the State of São Paulo (Coren-SP) facilitates the transition between the two decision-making models and the categories and subcategories associated with them. I dimensioned (determined staffing needs) of the nursing staff with the help of the Council (C9). We have the paperwork to administer the instrument, but we cannot because we have no time due to the shortage of professionals, thus making it impossible to administer it. We must stay in the hospital because a colleague is absent (B7). Every day, the nurse is obliged to perform the classification and put it on the online system (A1). I did it only because the Council asked, because according to the ordinance, we must participate, and I have no autonomy to hire, and neither of the managers want it (C9).

Specific types of communication were associated with management/governance styles: (Authoritarianism) This quantity has already been determined from top to bottom, so I did not participate in the process (A3). (Leadership) We decided together with the hospital's Nursing Board so that we could continue providing quality care in addition to health care nurses talking to each other about the classification process and its importance.

Difficulties included how to calculate staffing needs (dimensioning), how to engage or empower nurses and managers in the staffing decision-making process, and how to critically think about the meaning of numbers in the paperwork (versus another paper to fill out). I had to ask for help from the Council more than one time for the calculation, it was difficult to put the classification of patients on paper because we know the patients and we are classifying them mentally, but the Council wanted this in a spreadsheet. I had to do everything on my own because the health care nurses say that it is not their problem (C9). Then you take the clinical and psychiatric instrument and see that none meets our profile, and we try to get as close as possible (A4). It is extremely important to choose the appropriate instrument for institutional reality, because each institution has a patient profile (A1). We have already tried using several other instruments but were unable to show them (A2). Look, this instrument does not adapt all our profiles because each psychiatric unit has a profile, if there was an instrument adapted to each unit, it would be easier. The biggest challenge is to create something for our reality because we have no autonomy (B5). Really, the lack of an adequate instrument ends up making it difficult because we cannot get a sense of the real need, it is all about speculation, and we end up not having something we can rely on (C10). The managers indicated the need for more research in this field, stating that it is possible to build an evidence-based practice (EBP). Studies are always valid because mental health is very specific, and we do not count with management studies (A3). We are a teaching hospital and always discuss this topic with students (A4). I think that psychiatry lacks parameters and needs to move in this direction, which is commonly followed by other areas (B6).

The current ordinance on human resources in mental health is an aspect that greatly limits nurse staffing by managers, especially in type C hospitals: The Ministry of Health says that we are included in the ordinance, and we are aware of it, so we follow the ordinance and not the calculation given by the Council (C9). Cultural resistance comes from the administrative staff that follows the ordinance of the Ministry of Health; nursing professionals have always understood that it is better in another way, but it is difficult to defend it (C10).

The type of state administration has a direct impact on staffing need calculations, especially for type A and B institutions. Even if you dimension the nursing staff, which is not even ideal, it is necessary, then they do not approve it; many people do not understand this. They say that you only need to ask for it, but it is not like this. It was not approved by the government. So, you want 10 nurses, it gives you 8 (A2). I adapted as much as I could, but with the retirements and the crisis of the state, nurses who have not been replaced after leaving still face a little difficulty (E8). In contrast, it is more difficult because of the bureaucracy, it may be easier in a private hospital, but they will not provide you with an adequate number of nurses (B7). On the contrary, Coren-SP has the potential to determine better nurse staffing allocations. The State and the Institutions also need to understand this classification to provide an adequate staff allocation. It is not just internal management of the day. It goes beyond the larger, macro-level management of public policy. Thus, we need to change the ordinances, involving not only the executive power but also, especially, the legislative power. However, I see today a very positive attitude from the Council in taking this discussion to the State in order to increase the number of nurses (B6).

There are traces of the biomedical model in nursing practices: We have two nurses in the afternoon staying in the infirmary and passing through the sectors, evaluating and asking the technicians, who often say that the patient is not well. Therefore, the nurse calls the doctor on duty for the procedure (C9), but the psychosocial model is observed in another institution: So, we work with the support of everyone on the multidisciplinary team and everything is negotiated therapeutically (A3).

Fig. (2) is a diagram that depicts the biomedical model status of the current psychiatric setting on the left-hand side, with concepts associated with the psychosocial model on the right-hand side.

4. DISCUSSION

Our findings showed that the psychosocial model is related to important patient care changes for nursing teams, particularly increased nurse leadership autonomy and active nurse-nurse manager participation in staffing assignments (A3, A4, B5, B8, C10). In contrast, the biomedical model continued to have a strong authoritarian presence, according to other nurse managers (A1, A2, B7, C9).

Recent studies conducted in psychiatric institutions are scarce, and data comparing performance across institutions is limited. In general, the biomedical model still exists as in the 1970s, with nursing care in specific

Diagram of the psychiatric care setting from the perspective of nursing managers in psychiatry. Botucatu, SP, Brazil. 2017.

settings restricted by outdated notions based on macro-level hospital operation routines and technical/mechanistic nursing procedures, such as the preparation of medications [36]. The first Brazilian study on psychiatric nursing care was strictly based on a mechanistic, biomedical approach to care [14]. In another Brazilian study in a psychiatric setting, there was rudimentary evidence of the psychosocial model when patients reported how nurses at a psychiatric hospital gave them instructions about follow-up care and made sure they had their belongings at the time of discharge [36]. The legislation n.251 from the Brazilian Ministry of Health, which should support the principles of psychiatric reform from the point of view of human resources, still supports the biomedical model by saying that a nurse can psychosocially care for 240 patients in 12 hours of work, which limits managers’ capacity to staff more appropriately for psychosocial care. Therefore, while nursing legislation supports a psychosocial model, mental health legislation supports a biomedical model. For example, the management of potentially violent patients does not consider nurses’ clinical judgment or their role in team management of these patients [37, 38]. A clash of disparate models prevails, with significant legal restrictions in place that negate nurses’ role in the sociocultural dimension of the psychosocial model.

Evidence-based dimensioning/staffing of nurses in Brazilian psychiatric care settings is far behind other clinical specialties. Barriers identified through this study included limited adaptations of the Martins instrument for psychiatric patients and governance restrictions by institutions and the government. A sign of the biomedical model is the ongoing presence of nurse management and nursing care based on experience versus objective data and best evidence [20, 39]. Other barriers to evidence-based practice, which may prolong model transformation, include lack of institutional-academic partnerships; nurse-manager training and access to reliable PCS tools; managers’ personal characteristics, especially the difficulty of dealing with electronic databases; and organisational barriers such as culture and power hierarchies [40].

One critical obstacle to improving psychiatric nursing care is the absence of continuing education with evidence-based knowledge updates. In Brazil, continuing education is one of the skills included in the Brazilian National Curricular Guidelines (Diretrizes Nacionais Curriculares - DCN) for faculty of undergraduate nursing programmes. However, focusing on health education in undergraduate programmes does not address the knowledge gaps of post-graduate education, especially for managers who depend primarily on experience when making operational decisions. This study identified the limitations of managers who need skills pertaining to patient-centred care delivery.

In the psychosocial model, leadership is one of the most important managerial skills. Strong leadership contributes to teamwork and, consequently, to the achievement of better outcomes for staff, patients, and the organization [41, 42].

In Brazil, nursing managers are expected to carry out leadership/management skills indicated by the American Organisation of Nurses Executive [43]. These skills include technical knowledge, broad/strategic vision, management of material, financial and human resources, and relational skills, such as conflict management. These skills need to be introduced in undergraduate education and honed through nurses’ careers via continuing education [43]. In inpatient units, when nursing managers lack evidence-based leadership/management skills, the outcomes include unsystematic human resource planning, particularly ineffective nurse staffing. In one study, nurse managers without management certification had a ‘firefighting’ process for resolving staffing issues—evidence of little planning foresight [44]. As we found in this study, participants who had a specialisation in management had a more systematised discourse than managers who relied solely on their years of experience.

Organisational cultures that value control and rigid chain-of-command decision-making are associated with work settings where the individual skills of employees are undervalued and under-utlilised. There is some evidence that these rigid structures are also associated with employee mental health issues [21]. In comparison, when managers/leaders practice shared leadership, employees express greater job satisfaction and fewer perceptions of unmanageable physical and psychological workloads.

Although leadership aims to promote evidence-based practice, in many instances mentioned in this study, managers still use inductive, non-generalisable approaches in decision making. The inductive principle of empiricism, however is not valid or sustainable in complex, ever-changing contexts [45] Decision making is one of the basic cognitive processes of human behaviour, because an option or a course of action is chosen based on defined criteria. In management, this process takes place through systematic thinking: Nurse managers need to consider if they have enough data, and they need to know where to obtain valid and reliable data. In Brazil, Federal Nursing Council (COFEN) supports managers’ use of databases and available research, although as mentioned, more research is needed to determine how to best implement model transformation in psychiatric settings [46-48].

Psychosocial model implementation in Brazilian psychiatric settings will be strengthened through refinement and validation of PCS, such as the Martins instrument. This study showed how managers are using the tool, although they reported many difficulties with it in their settings. Managerial barriers involved the tool, which needs better refinement and validation through further research endeavors. The capacity of PCS to make a positive difference, however, will also depend on managerial skills pertaining to data use and implementation e.g., staffing decisions at different organizational levels--teams, units, departments, and organisations. In addition, managers will only advance their knowledge and skills within organisational cultures that value managerial autonomy and collaborative decision-making with staff, patients, and families.

The limitations of this study are due to the small number of participants. However, since this is a qualitative study, the aim is not to generalise the data. Due to the scarcity of recent studies on the management of psychiatric nursing, especially the use of PCS, these data could not be adequately compared.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this study revealed that the management of psychiatric nursing is undergoing a change in practices. Understanding how psychiatric care is performed within the psychiatric setting from a managerial perspective is a major advance in the area, as other studies only address psychiatric care from a medical pathology (biomedical) perspective.

In this study, 50% of the institutions evaluated used PCS as a management tool. Our findings also showed that although the Regional Nursing Council of the State of São Paulo (Coren-SP) has been working actively to inform evidence-based managerial practices, gaps in managerial skills persist in psychiatric care settings.

Thus, it is suggested that continuing education is the key to managerial upskilling as psychosocial transformation moves forward—albeit slowly. The quality of psychiatric care has always been under scrutiny, given the history of psychiatric care and inhuman practices. Nursing has an important role to play in the advocacy of scientific and humanitarian principles associated with the psychosocial model and objective use of data related to holistic patient care needs (i.e., validated PCS).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

L.V., W.S.: Study conception and design; S.C.B.: Validation; M.M.: Analysis and interpretation of results. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| CAPS | = Centro de Atenção Psicossocial- Psychosocial - care centres |

| COFEN | = Conselho Federal de Enfermagem - Federal Nursing Council |

| Coren-SP | = Conselho Regional do Estado de São Paulo - Regional Nursing Council of the State of São Paulo |

| DCN | = Diretrizes Nacionais Curriculares - Brazilian National Curricular Guidelines |

| EBP | = Evidence-based practice |

| PCS | = Patient classification systems |

| RAPS | = Redes de Atenção Psicossocial - Psychosocial care networks |

| SUS | = Sistema Único de Saúde - Brazilian National Health System |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This research project was approved by the relevant research ethics committee under protocol number CAAE: 56156616500005411 and protocol 1.657.831, meeting the criteria of the National Health Council.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Data was collected after research participants signed the Informed Consent Form.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All authors contributed substantially to the design, performance, analysis, or reporting of the work and are required to indicate their specific contribution.