All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

A Bundle of Best Practices for Short Peripheral Venous Catheterization in Hospitalized Patients: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Objective

This study aims to construct a bundle of practices for short peripheral venous catheterization in hospitalized adult and older adult patients, based on best practices available in the scientific literature.

Methods

A methodological study was carried out in two stages: scoping review and bundle construction. The review was conducted according to the JBI recommendations for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews, answering the following question: “What are the best nursing practices for short peripheral venous catheterization in adult and older adult patients hospitalized in clinical wards?” Studies that included adult and older adult patients hospitalized in clinical wards, addressing nursing care in the management of short peripheral venous catheters to prevent iatrogenic complications, using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods approaches, were included. Systematic reviews, expert opinions, and gray literature were also considered.

Results

Nine documents published in different countries with recommendations to prevent complications of short peripheral venous catheterization were included. The bundle was constructed with 25 interventions divided into client preparation, insertion, maintenance/handling, and removal that should be followed to guide good practices in the management of short peripheral venous catheters.

Conclusions

Interventions for short peripheral venous catheters were identified and deemed relevant to prevent complications. There is an urgent need to develop tools to systematize care and to train healthcare teams. Thus, the importance of this paper can be seen in having built this product (bundle) that can guide the clinical practice of several nursing professionals. Research is recommended to be carried out to construct and validate bundles so that they can improve clinical nursing practice and patient care.

1. INTRODUCTION

Peripheral venous catheterization is a central pro- cedure in the clinical care of hospitalized patients.1 It is estimated that 70% of hospitalized patients require a short peripheral venous catheter,2 as this device is used to infuse medications, solutions, electrolytes, and blood components, and to draw blood for laboratory tests [1-3].

The insertion of a peripheral venous catheter is an invasive procedure performed by the nursing team under the supervision and guidance of a registered nurse.1-3 Venipuncture for insertion of a short catheter into a peripheral vessel involves fixation and maintenance, assessment of vascular patency, dressing and skin integrity, and removal and post-removal care [1, 3, 4].

It is important to note that inadequate vascular access management can lead to iatrogenic complications [1, 4]. Risk factors for the development of complications include issues related to technique, professional skill in performing the puncture, catheter dwell time, types of infused fluids, site, fixation, and intrinsic patient factors such as age, sex, and venous network conditions [1-3].

Complications associated with peripheral venous catheterization include hematoma, phlebitis, bloodstream infection, thrombophlebitis, infiltration, extravasation, and occlusion.1 These complications are currently considered indicators of the quality of care provided, as they directly affect patient care [3], leading to prolonged hospitali- zation, venous compromise, repeat punctures, and sometimes failure of therapeutic regimens, as well as a negative impact on safety [2, 3].

However, these complications can be prevented by implementing systematic prevention measures based on evidence-based care by the nursing team [1-4]. However, the scientific literature indicates gaps in the nursing team's knowledge of best practices related to peripheral venous catheterization [1].

The present study is therefore relevant as it is the nursing team that is responsible for the insertion, main- tenance/handling, and removal of short peripheral venous catheters. In this sense, the decision to conduct a scoping review on this topic was made because it allows a more accurate mapping of what is recommended in the scientific literature regarding best practices with short peripheral venous catheters and, from this, to support the production of a bundle capable of contributing to safe and quality nursing care, to be undertaken by professionals involved in patient care in units where intravenous therapy is performed.

Initially, the topic was searched in these databases just to provide the state of the art on the topic: Virtual Health Library (BVS in Portuguese) and PubMed®, but no scoping reviews were found, which supported the decision to conduct a scoping review to obtain the necessary elements for the next stage. Subsequently, when carrying out the scope review, the search was expanded to more bases. The aim of this work is to construct a bundle of practices for short peripheral venous catheterization in hospitalized adult and older adult patients, based on best practices available in the scientific literature.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design

The methodological study was developed in two stages: i) Scoping review, conducted according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) recommendations for scoping reviews, with the protocol registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/8jnsr/; and ii) Construction of a bundle of best practices related to short peripheral venous catheterization.

2.2. Data Collection

Data collection was conducted in December 2021, guided by the research question: “What are the nursing practices related to short peripheral venous catheteri- zation in adult and older adult patients hospitalized in clinical wards?”

In terms of databases, the following were selected: Índice Bibliográfico Español en Ciencias de la Salud (IBECS), Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences (LILACS), Nursing Database (BDENF), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE via PubMed), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE). In addition, gray literature such as society websites and Brazilian Ministry of Health manuals were searched.

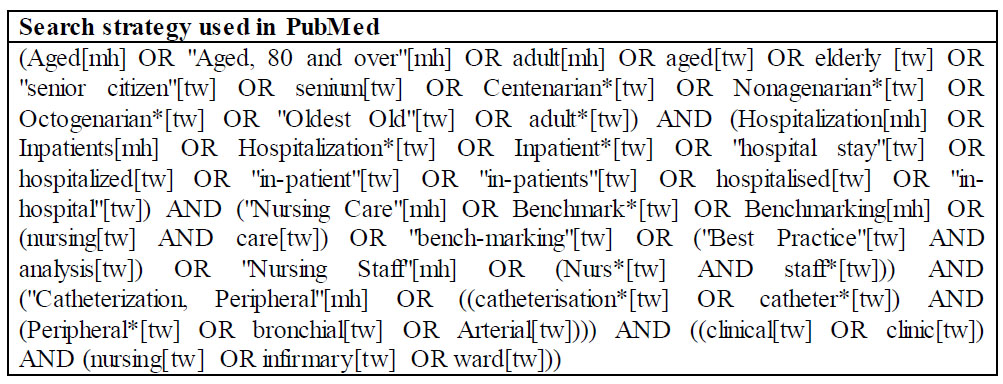

The search was conducted in two stages. The first stage involved an “advanced search” to identify MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) and DECS (Health Sciences Descriptors) descriptors. The Boolean operators OR and AND were used, following the search strategy shown in Fig. (1) prepared by a specialist librarian. Furthermore, studies were selected from the gray literature that met the inclusion criteria of this scoping review.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

Studies investigating best practices with short peripheral venous catheters in adult and older adult patients hospitalized in clinical wards, addressing different strategies of catheter care, and aiming to demonstrate their efficiency and effectiveness, as well as the correct way to deliver therapy for optimal outcomes, related to any discipline of health were included.

Quantitative and qualitative approaches, mixed methods, systematic reviews, and expert opinion studies in all languages, conducted on humans in a hospital setting between 2017 and 2021, were then selected. Animal or in vitro experimental research was excluded.

After the search was completed, duplicate removal was performed using the Mendeley Reference Manager for Desktop tool. Article selection by title and abstract analysis was performed by two independent reviewers (double-blind) based on eligibility criteria, with a third reviewer involved to resolve disagreements. Two independent reviewers, who were authors of the study, read the articles in full, with a third reviewer involved to resolve disagreements.

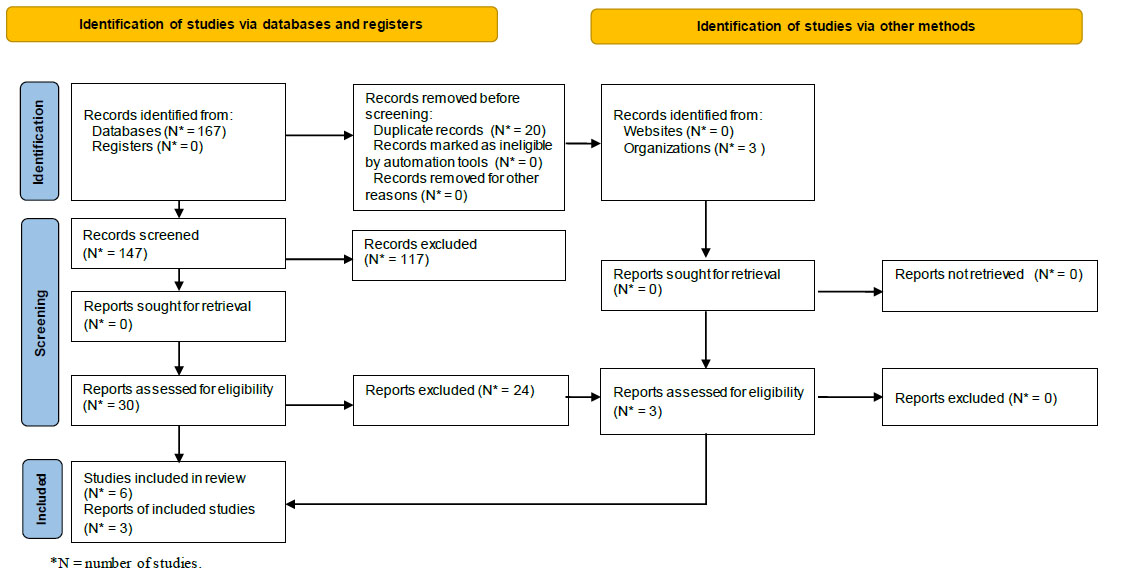

Following the selection of citations, a Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA ScR) flowchart outlining the step-by-step process was presented in this study, along with the results obtained from the gray literature.

2.4. Data Treatment and Analysis

Data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers and imported into a tool created by the reviewers. The selected data related to population, concept, context, study methods, and nursing care with peripheral venous catheters are relevant to the research objective. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

The data were presented using figures, aligning with the objectives of the scoping review. From these data, a bundle of best practices for using short peripheral venous catheters, regarding the role of the nurse in these best practices, was developed.

The search strategy used in the PubMed database.

Flowchart of the study selection process.

3. RESULTS

To determine the results, a pairwise analysis was conducted based on the research question, as shown in the flowchart in Fig. (2).

After careful analysis, six articles, one technical note, and two guidelines were included, for a total sample of nine papers. The articles were from the following countries: one from Spain, one from Portugal, three from Brazil and one from Singapore. Regarding the guidelines, the publications were: one in the United States of America and two in Brazil. In terms of focus, all addressed recommendations to prevent potential complications of short peripheral venous catheterization. Of note, the productions occurred: one in 2022, four in 2021, one in 2020, one in 2019, one in 2018, and one in 2017. The 9 selected papers are described in Table 1.

After a careful review of the materials and assessment of the key care elements to be included, the scope of the bundle encompassed 25 interventions, divided into the following axes: client preparation, insertion, maintenance/ handling, and removal, as described in Table 2.

4. DISCUSSION

The scoping review allowed the identification of best practices based on current scientific evidence for the insertion, maintenance, and removal of short peripheral catheters, which became the basis for the construction of a bundle of 25 care items ranging from patient preparation to device removal.

The Brazilian National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) and the Infusion Nurse Society (INS) provide a structured, step-by-step approach that includes hand hygiene, skin preparation, puncture procedure, and care for maintenance and removal of short peripheral venous catheters, based on research by selected expert groups aimed at identifying evidence-based best practices [5-7].

Regarding hand hygiene, there is a consensus that it should be performed before and after insertion and any manipulation of devices [5-7]. In addition, ANVISA and INS recommend that healthcare professionals perform hand hygiene at five moments: before touching the patient, before performing a clean/aseptic procedure, after exposure to body fluids, after touching the patient, and after touching surfaces near the patient [5, 6].

Regarding the choice of product, there is disagreement regarding the concentration of the alcohol solution, as the INS recommends an alcohol-based product with a concentration of at least 60% ethanol or 70% isopropyl alcohol [6], while ANVISA recommends an alcoholic hand rub with a concentration of 60 to 80%.7 Both suggest the use of water and soap when hands are soiled [6, 7].

It is noteworthy that ANVISA has some differences with INS regarding the choice of puncture site since the former mentions the names of the forearm veins (cephalic, basilic, median antebrachial, and elbow) and includes the dorsum of the hand as one of the possible sites for cannulation, which is confirmed by INS. However, INS cautions that such a site may be used for short-term therapy [5-7].

To increase the stability of the catheter within the vessel and thus reduce vascular trauma, it is recommended to trim excess hair from the site with scissors prior to puncture [5-7], while the use of bandages or other immobilization devices after cannulation is contraindicated [5, 6].

Regarding skin antisepsis, the point of divergence identified was that both ANVISA materials indicate skin preparation by rubbing with alcohol-based solution without further specification [5-7], while INS suggests preferring the use of alcoholic chlorhexidine, with 70% alcohol as a second option.6 All three recommend waiting for the product to dry before performing the venipuncture [5-7].

Regarding the insertion of short peripheral venous catheters, there is a consensus among the guidelines to avoid flexed areas, limbs with open wounds, infections in the extremities, veins affected by infiltration, phlebitis and/or necrosis, areas with previous infiltration or extravasation, areas where procedures will be performed, and the lower limbs due to the increased risk of embolism and thrombophlebitis [5-7]. However, ANVISA and INS include the additional recommendation not to cannulate limbs with arteriovenous fistulae [5, 6].

Puncture attempts should be limited to two per practitioner according to guidelines [5-7]. However, ANVISA recommends no more than four attempts per patient [5-7], while INS suggests that after the second unsuccessful attempt, a nurse with greater expertise should be called and alternative routes of drug administration considered [6]. There is consensus that a new catheter should be used for each cannulation attempt, as well as the use of visualization methods in individuals with difficult venous access and/or after puncture failure [5-7].

However, the INS makes an exception for vesicants and irritants, stating that in an emergency, vasopressor infusion can be started through a peripheral venous access, but should be transferred to a central venous access as soon as possible, within a period of 24 to 48 hours [6].

Among the articles reviewed, a study conducted in a university hospital in Spain, which examined the difficulties faced by nursing and medical teams in complying with the recommendations of a bundle for the prevention of complications related to vascular access devices, identified as the most prevalent difficulties before and after training the removal of unnecessary catheters, the daily maintenance of catheter sites, the aseptic management of venous catheter systems, and the exchange of peripheral venous access devices according to institutional protocols [8].

Although the INS, which provides international guidelines for best practices in vascular access, recommends that the peripheral venous catheter be changed when clinically indicated [6], some hospital institutions continue to adopt scheduled catheter changes in their protocols [8, 9], as this INS guidance, which is also contained in documents, is conditioned on the adoption of good practices with vascular access devices [5-7].

| Study (author/year) | Title | Study Design | Recommendations/study Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brazilian National Health Surveillance Agency, 2022 [5] | Safe practices for preventing incidents involving peripheral intravenous catheters in healthcare services | Technical note ‡‡GVIMS/GGTES/DIRE3 †ANVISA § N. 040/2022 |

Wash your hands before and after insertion and any type of manipulation of the peripheral intravenous catheter; Select the catheter according to the access conditions and the objective, duration of therapy, and viscosity of the substances that will be infused; Do not infuse vesicant solutions or those with an osmolarity above 900 mOsm/L and/or more than 10% dextrose; Give preference to catheters with smaller caliber and cannula length; Puncture, preferably, the veins in the dorsal and ventral region of the forearm, such as the cephalic, basilic, median veins of the forearm, elbow, and back of the hand; Avoid dominant limb, flexion region, limbs with an open wound, with infection in the extremities, veins compromised by infiltration, phlebitis, and/or necrosis, regions with previous infiltration or extravasation, areas where procedures will be performed and limbs with arteriovenous fistula; The veins of the lower limbs should not be cannulated, unless extremely necessary, due to the risk of embolism and thrombophlebitis; Use visualization methodology for patients with a difficult venous network and/or after an unsuccessful puncture attempt; Perform a maximum of two puncture attempts per professional, totaling four per patient, using a new catheter for each attempt on the same patient; Remove excess hair from the area where the puncture will be performed, with scissors, to facilitate the fixation of the dressing/covering; Prepare the skin by rubbing the area that will be punctured with an alcohol-based solution, wait for the product to dry, and do not touch the area again after antisepsis; Stabilize the catheter with an aseptic technique, do not use sutures, non-sterile tapes, or immobilization devices; Occlude the puncture site with a sterile covering, preferably a transparent waterproof membrane. Semi-occlusive coverage, with sterile gauze and adhesive tape, should only be used for accesses that will remain for up to 48 hours; Identify the dressing with date, time, catheter caliber and name of the professional who performed it; Protect the site and connections with plastic during the bath; Change the cover, using aseptic technique, when there are signs of contamination or when it is damp, dirty, loose and/or its integrity is compromised; Disinfect the connectors with 70% alcohol or 0.5% alcoholic chlorhexidine before infusions; Perform aspiration and flushing with 0.9% saline solution in a 10 ml syringe, before each infusion; Do not force flushing with a syringe of any size, in case of resistance, evaluate the factors; Lock the device using the positive pressure technique (flushing, close the clamp and disconnect the syringe); Assess the insertion site and adjacent regions every 4 hours, through inspection and palpation, for the presence of heat, redness, edema, drainage of secretions, bleeding, hematoma, bullous or abrasive injuries related to the covering and evaluate reports of pain or discomfort on the part of the patient; Guide patients and companions regarding catheter maintenance care, as well as signs of complications; Assess daily the need for the catheter to remain in place and remove it when there is no more intravenous medication prescribed or when the catheter has not been used for more than 24 hours; Do not change the catheter within a period of less than 96 hours, unless contamination, complications or malfunction are suspected; Routinely evaluate the catheter, the decision to change the catheter in a period above 96 hours or when clinically indicated, will depend on good institutional practices. |

| Infusion Nurse Society, 2021 [6] | Infusion Therapy Standards of Practice |

Guideline | Clean your hands with an alcohol-based product with a concentration of at least 60% ethanol or 70% isopropyl alcohol, before and after the insertion and removal of vascular access devices, as well as the administration of infusions. If your hands are dirty, use soap and water; Use vascular visualization technology for people with veins that are difficult to observe and palpate; Do not insert and/or maintain a short peripheral intravenous catheter if intravenous therapy is not prescribed; To choose the puncture site, one must evaluate the type and duration of infusion therapy, the patient's preference, and physiological condition such as age, diagnosis, comorbidities, vascular and skin condition at the insertion site; Avoid inserting a catheter in areas of flexion, areas with skin affected by injuries, regions with planned procedures, limbs with arteriovenous fistulas, lower limbs and on the patient's dominant side; Do not puncture veins compromised by previous cannulation, infiltrated, sclerosed, with erythema, striations and/or fibrous cord; Give preference to the veins in the dorsal and ventral region of the forearm. Hand veins may be considered for short-term therapies; Continuous infusion of irritating and vesicant medications should be avoided. In emergency situations, medications such as vasopressors can be started through a peripheral access, but a central venous access must be inserted as quickly as possible, within 24 to 48 hours; Use, in peripheral access, substances with a maximum concentration of 10% dextrose and/or 5% protein; Choose the catheter with the smallest diameter possible, according to the solution that will be infused, preferably 20 gauge to 24 gauge. For elderly patients or those with limited vein options, 22 to 26 gauge can be used, aiming to reduce insertion-related trauma; Before the puncture, remove excess hair from the insertion site using scissors or a shaver; Conduct skin antisepsis, preferably with alcohol-based chlorhexidine or 70% alcohol, letting the product dry naturally and do not touch the site again; Restrict to 2 puncture attempts per professional and use a new catheter for each of them; if both are unsuccessful, refer the patient to a nurse with a higher skill level or consider alternative routes of medication administration; Disinfect the catheter hub by rubbing 70% alcohol or alcohol-based chlorhexidine for 5 to 15 seconds. Wait for the alcohol to dry for 5 seconds and the alcoholic chlorhexidine for 20 seconds; Perform a pulsatile flush with 0.9% sodium chloride in a 10ml syringe before and after infusions, as well as to lock the catheter. Use positive pressure technique to minimize blood backflow into the lumen of the vascular access device; Check the permeability of the catheter by aspiration of blood followed by flushing, in all circuit routes, before infusions. If you encounter resistance, do not force the infusion with any size syringe; Avoid using non-sterile tape and/or bandage, with or without elastic properties, to fix the catheter; Evaluate the infusion system, every 4 hours, from the insertion site to the solution container for the integrity of the system, dressing and skin, signs of complications and validity of the set; Avoid routine exchange of functioning catheters, remove the device when: you do not have a prescription for intravenous medication or if the access has not been used for more than 24 hours; present erythema, edema, purulent secretion, palpable venous cord, extravasation, infiltration, adjacent skin injury, infection, nerve injury, report of pain/sensitivity by the patient. Use a phlebitis assessment scale and guide the patient and their caregivers regarding signs of complications. Catheters inserted with failed aseptic technique should be exchanged as quickly as possible, between 24 and 48 hours. Label the dressing with the puncture date. Protect the catheter and connections with plastic when bathing the patient. |

| Brazilian National Health Surveillance Agency, 2017 [7] | Healthcare-associated infection prevention measures | Guideline | Clean hands with alcoholic hand preparation with a concentration of 60 to 80% before and after insertion, removal, manipulation or dressing change of catheters. When visibly dirty, use water and liquid soap; Select the peripheral catheter according to the intended objective, duration of therapy, fluid viscosity, fluid components and venous access conditions, giving preference to catheters with smaller caliber and cannula length; Do not infuse vesicant solutions with an osmolarity greater than 900 mOsm/L and/or more than 10% dextrose; The puncture site should preferably be the dorsal and ventral regions of the forearm. Lower limb veins should not be cannulated due to the increased risk of embolism and thrombophlebitis; Avoid the dominant limb, flexion region, limbs with open wounds, infections in the extremities, veins compromised by infiltration, phlebitis, necrosis, areas with previous infiltration and/or extravasation, areas with other planned procedures; Use visualization method for people with difficult venous network; If necessary, remove excess hair from the area where the puncture will be performed, using scissors. Prepare the skin by rubbing an alcohol-based solution, waiting for the product to dry, and not touching the puncture site after antisepsis; Use a new catheter in case of a new puncture attempt on the same patient; Limit to two attempts per professional, not exceeding four in total; Stabilize the catheter using aseptic technique, preferably in a way that does not impede the assessment of the insertion site and/or the infusion of therapy, as well as not using sutures or adhesive tapes; Protect the puncture site with a sterile covering, preferably a semi-permeable transparent membrane. The semi-occlusive covering, with gauze and sterile adhesive tape, should be used in accesses that will remain for up to 48 hours; Change the cover, using aseptic technique, when contamination is suspected, it is damp, dirty, peeling off and/or its integrity is compromised; Protect the site and connections with plastic during the bath; Perform pulsatile flushing (flush pause) with a 10 ml syringe and 0.9% sodium chloride, before and after infusions, as well as a reflux test; Do not force flushing with any size syringe; Use positive pressure technique and catheter lock after each use; Assess the insertion site and adjacent regions every four hours for the presence of pain, redness, edema, and purulent drainage; Assess the need to maintain the catheter daily and remove it if intravenous infusions are no longer prescribed or if it has not been used for more than 24 hours; Do not routinely change the catheter within a period of less than 96 hours. In institutions where good practices are adopted in the handling of peripheral venous catheters, these can remain in place for a period of more than 96 hours, according to clinical assessment; Remove catheters that show signs of complications, contamination and/or malfunction. |

| Aparicio et al., 2020 [8] | Difficulties in the implementation of recommendations to prevent the complications associated with vascular access devices | Descriptive cross-sectional study. | In the pre-training period, 150 professionals responded to the questionnaire and 184 after training, with most of the sample being nurses. The difficulties identified as most prevalent in complying with the bundle recommendations, in both phases, were: removing unnecessary catheters; perform daily maintenance of catheters; handling and/or hygienic access to the circulatory system, through the device; exchange of short peripheral venous catheters according to institutional protocol. In relation to the factors associated with these difficulties, they were identified as professionals in the nursing category and surgical hospitalization unit. |

| Gunasundram et al., 2021 [9] | Reducing the incidence of phlebitis in medical adult inpatients with peripheral venous catheter care bundle: a best practice implementation project | Pre- and post-test study associated with the audit. | The measures that constituted the short peripheral venous catheter care bundle, developed through this study, were: 1) LINE framework: location, puncture date, catheter caliber and expiration date. 2) Simple figure indicating the locations and superficial veins commonly used for insertion of a short peripheral venous catheter. 3) Visual representation of the Phlebitis Assessment Scale with the respective interventions. 4) Check the patency of the catheters once every shift or every 8 hours. 5) Check the puncture site for the integrity of the dressing and the stabilization of the peripheral vascular access device, once every shift. 6) Provide educational pamphlets to the patient and family about the signs and symptoms of phlebitis. 7) Evaluate the clinical indication of maintaining the short peripheral venous catheter once per shift and removing it as soon as its use is no longer justified. 8) Minimize the use of plaster after catheter removal and apply firm pressure to the site afterwards. |

| Silva et al., 2021 [10] | Nursing performance without control of blood current infection | Descriptive, documentary, retrospective study. | Train nursing team professionals to adopt good practices in maintaining vascular access to prevent catheter-related bloodstream infections. It was listed as fundamental: 1. Identification of the access dressing with date, time and name of the professional who performed the puncture; 2. Use of a sterile transparent dressing to fix the catheter and protect the insertion ostium; 3. Performing aspiration and flushing before infusions. |

| Furlan et al., 2021 [11] | Evaluation of phlebitis adverse event occurrence in patients of a Clinical Inpatient Unit | Exploratory-descriptive, documentary, retrospective study. | The notifications analyzed indicated that most patients who presented with phlebitis were male, aged between 60 and 69 years, with intravenous access lasting less than 4 days, with a predominance of those with a needle device installed within less than 24 hours for completion. antibiotic therapy and housed in beds far from the nursing station. There was a predominance of grade 2 phlebitis and mild damage classification, with the nurse being the professional who conducted most notifications. |

| Braga et al., 2018 [12] | Phlebitis and infiltration: vascular trauma associated with the peripheral venous catheter | Descriptive cohort study. | Most catheters were removed within the first 24 hours after insertion, due to phlebitis and infiltration. Regarding the incidence rate, phlebitis was 43.2 and infiltration was 59.7 per thousand catheters/day. The main risk factors for phlebitis were the length of hospital stay and the number of catheters inserted in the patients, while for infiltration they were antibiotic therapy with Piperacillin/Tazobactam, and the number of catheters inserted in the patient. The average puncture per patient, throughout the hospitalization period, was 6.5 times. Regarding success, the average was 1.5 attempts until successful peripheral venipuncture. The site of choice for short peripheral venous catheterization was the back of the hand and forearm, respectively. While the most used catheters were 22G and 20G and the dressing was sterile transparent film. |

| Santana et al., 2019 [13] | Nursing team care actions for safe peripheral instravenous puncture in hospitalized elderly people. | Exploratory descriptive study. | The first options for the puncture site were the forearm and back of the hand, followed by the arm and antecubital fossa. Considering the greater visibility of the vessel and the preservation of the patient's mobility to avoid accidental removal of the catheter; When choosing the device, professionals considered the caliber and length of the catheter; the tortuosity and size of the vein, in addition to the nature of the solution to be infused; Factors related to skin sensitivity and characteristics of the elderly person's venous network were also observed. |

† ANVISA = Brazilian National Health Surveillance Agency.

§ N = Number.

The guidance to remove the catheter as soon as possible is evident, i.e., when no intravenous medications are prescribed, when the access has not been used for more than 24 hours, or when there are signs of complications, contamination, and/or malfunction. Daily assessment of the catheter, site, and adjacent areas is therefore necessary [5-9].

Regarding device maintenance, it is recommended to perform backflow testing and pulsatile flushing (flush pause) with a 10 ml syringe and 0.9% sodium chloride solution before and after infusions to assess device patency, prevent chemical obstruction from drug precipitation, and prevent hematogenic obstruction from fibrin sheath and/or clot formation within the catheter.

| Patient Preparation | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Assessing the condition of the venous network and skin at the insertion site. |

| 2. | Selecting the catheter according to access conditions, objective, duration of therapy and viscosity of the substances to be infused, and giving preference to a smaller caliber catheter and cannula length. |

| 3. | Removing excess hair from the insertion site by trichotomy with scissors. |

| 4. | Preparing the skin by rubbing the area where it will be punctured with 0.5% alcoholic chlorhexidine or 70% alcohol. Let the product dry naturally and do not touch the area again. |

| Insertion | |

| 5. | Cleaning your hands with an alcohol solution before and after inserting the catheters; if hands are dirty, it is recommended to use soap and water first. |

| 6. | It is advised to avoid inserting catheters in areas: flexion, veins compromised by infiltration, phlebitis, necrosis, with previous infiltration and/or extravasation; of limbs with arteriovenous fistula; of regions with wounds or with scheduled procedure and dominant limb. Lower limb veins should only be used, if necessary, due to the elevated risk of embolism and thrombophlebitis |

| 7. | Preferably, veins from the ventral and dorsal region of the forearm must be chosen. Hand veins may be considered for short-term therapies |

| 8. | In case of failure, we restrict to two puncture attempts per professional, not exceeding four attempts on the same patient. We use a new catheter for each of them. |

| 9. | We use the visualization method for people with difficult venous network. |

| 10. | Stabilizing the catheter using an aseptic technique, in a way that does not impede the assessment of the insertion site and/or the infusion of therapy, as well as not using adhesive tapes. |

| 11. | Occluding the puncture site with a sterile covering, preferably a semipermeable transparent membrane. It is recommended that semi-occlusive dressings, with gauze and sterile adhesive tape, be used on accesses that will remain for up to 48 hours. |

| 12. | Identifying the dressing with the puncture date, the caliber of the catheter used and the name of the professional responsible for the puncture. |

| Maintenance/Handling | |

| 13. | Cleaning hands with alcohol solution before and after handling or changing catheter dressings. |

| 14. 15. |

Disinfecting the catheter hub by rubbing alcohol-based chlorhexidine or 70% alcohol for 5 to 15 seconds before and after infusions. Waiting for drying for 20 seconds if alcoholic chlorhexidine and 5 seconds if 70% alcohol. |

| 16. | Check the permeability of the catheter by performing blood aspiration followed by a pulsatile flush (push pause) with 0.9% sodium chloride in a syringe larger than or equal to 10 ml, before and after infusions, in all circuit routes. If resistance occurs, we do not force the infusion with syringes of any size. |

| 16. | Locking the catheter with a positive pressure technique after each use. |

| 17. 18. |

It is advised to avoid the continuous infusion of irritating and vesicant medications. In emergencies, such medications can be started through peripheral access, but the insertion of a catheter into central venous access must be performed as quickly as possible, within 24 to 48 hours. We do not infuse solutions with dextrose concentration greater than 10%, protein greater than 5%, and/or osmolarity above 900 mOsm/L. |

| 19. | Assessing the integrity of the infusion system, skin, puncture site, signs of phlebitis (using a standardized scale), presence of infiltration, extravasation, integrity of the dressing, and stabilization of the peripheral vascular access device once per shift. |

| 20. | Changing the cover, using an aseptic technique, when it is damp, dirty, peeling off and/or its integrity is compromised. |

| 21. | Protecting the puncture site and connections with plastic during the bath. |

| Withdrawal | |

| 22. | Cleaning hands with alcohol solution before and after removing catheters. |

| 23. 24. |

It is advised to avoid scheduled replacement of functioning catheters. In institutions where good handling practices are adopted, these can remain for a period of more than 96 hours, according to clinical assessment. Assessing the need to keep the catheter in place daily and remove it if intravenous infusions are no longer prescribed, the device has not been used for more than 24 hours, or shows signs of complications. |

| 25. | Remove inserted catheters, in emergency situations, with failure of aseptic technique, as quickly as possible, between 24 and 48 hours. |

Positive pressure locking (flushing, closing the clamp, and disconnecting the syringe) at the end of flushing prevents blood reflux into the device, thereby reducing the risk of colonization. It is emphasized that any perceived resistance indicates the need for catheter replacement [5-7].

In addition, with regard to maintenance, ANVISA and INS recommend the disinfection of connectors (hub scrubbing) by rubbing the hub with alcoholic chlorhexidine or 70% alcohol for a period of 5 to 15 seconds before and after infusions, waiting for alcoholic chlorhexidine to dry for 20 seconds and 70% alcohol for 5 seconds [5-7].

The literature analyzed evaluated peripheral venous catheters installed in patients admitted to medical wards of a federal hospital located in Rio de Janeiro, with the aim of analyzing factors associated with bloodstream infections related to the use of peripheral venous catheters. It was considered essential to identify the dressing with the date, time and name of the professional who performed the puncture; the use of a sterile transparent dressing to secure the catheter and protect the insertion site from contact with external micro- organisms; aspiration [10] and flushing before infusions, the latter also mentioned in other studies [8-10].

It is worth noting that the ANVISA and INS guidelines advocate the use of sterile transparent film dressings, as they not only provide aseptic protection of the catheter insertion site but also allow daily assessment of the insertion site and adjacent skin [5-7]. In addition, ANVISA recommends more comprehensive identification of the dressing, including the date, time, catheter size, and name of the professional who performed the puncture.5 All three organizations recommend changing the dressing with an aseptic technique if it becomes soiled, wet, detached, and/or has compromised integrity [5-7].

Studies on phlebitis emphasize the importance of analyzing patient characteristics, chemical properties, osmolarity, pH of solutions to be infused, and duration of treatment prior to puncture, and selecting the smallest possible catheter size based on this information [9, 11, 12]. These measures are in line with ANVISA and INS guidelines [5-7]. They also suggest the use of disinfected tourniquets and sterile semipermeable film dressings [9, 11, 12].

In order to standardize the assessment and recording of phlebitis signs and to enable the identification of severity, these articles suggest daily assessment using a validated phlebitis scale, so that adverse events are identified early and the catheter is removed at the first sign of phlebitis, thus interrupting the progression of the inflammatory process and reducing the risk of developing temporary or permanent damage [9, 11, 12].

A product from a study conducted in a Singapore hospital was included in the bundle aimed at reducing the rate of phlebitis, with a visual presentation of the Phlebitis Assessment Scale and related interventions [9], along with a recommendation for professionals to provide patients and families with educational booklets on the signs and symptoms of phlebitis. This strategy, which has been adopted by various literatures, aims to increase patient safety, and positively impact the quality of care provided [9, 11, 12].

In the literature, antibiotics administered through short peripheral venous catheters have been shown to increase the risk of phlebitis and infiltration compared to patients not receiving this class of drugs. This underscores the importance of analyzing the type of solution, route of administration, and duration of therapy to consider using a different type of catheter, such as the Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC). The tip of the PICC is placed in a larger caliber vein (superior vena cava) and the high blood flow allows for greater hemodilution, factors that significantly reduce the risk of phlebitis and thrombophlebitis [11, 12].

Training of professionals to build capacity to prevent complications related to vascular catheters was mentioned in 04 of the 06 articles analyzed [8-10, 13]. The responses of the participants in the article evaluating the care of the nursing team in peripheral intravenous puncture in hospitalized elderly showed that the professionals considered aspects related to the clinical conditions, venous network, and skin of the elderly, took into account issues such as maintaining autonomy and vein visibility, but showed a lack of parameters in the choice of device gauge. This demonstrates a lack of systematization in the planning of the peripheral venous puncture procedure [13].

The literature also discusses that approximately one year after the implementation of a bundle training, there is a decrease in compliance by professionals, almost to the same level as before the implementation. The authors suggest that in order to maintain compliance with protocols and bundles, institutions need to conduct regular education sessions to remind staff of the measures and allow them to question and correct their practice [8].

Finally, a care bundle for short peripheral venous catheters for adult and elderly hospitalized patients was developed based on the exposition. This bundle includes 25 interventions divided into categories: patient preparation, insertion, maintenance/handling, and removal. It is emphasized that the next step will include expert validation and appearance validation, further enhancing its methodological robustness for implementation in the clinical wards of a university hospital in Rio de Janeiro.

Limitations of the study include the temporal scope of the article search, which may have limited the selection of some papers. However, efforts were made to include studies that met the eligibility criteria based on the most recent literature recommendations [6, 7]. In addition, the methodological quality of the studies was not assessed.

CONCLUSION

Based on a scoping review conducted as part of this study, it was possible to develop an inventory of the most important nursing practices for short peripheral venous catheters, including skin preparation, catheter insertion, maintenance, and removal, aimed at preventing complications.

This inventory highlighted the urgency of developing tools to systematize clinical nursing practice with the goal of providing qualified care free from the risks of carelessness, incompetence, and negligence. It also emphasized the need to plan training programs for teams to implement best practices for short peripheral venous catheterization procedures. In summary, these are the ways to reduce the incidence of adverse events and increase patient safety in units where intravenous solutions are infused.

Finally, it also underscores the need for further research on this topic, which is so relevant and necessary for health care and nursing support. This study serves as a turning point for possible future research efforts.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

All authors contributed equally to the study conception, design, data collection, analysis and inter- pretation of results. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript under the heading of Author.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| JBI | = Joanna Briggs Institute |

| OSF | = Open Science Framework |

| CINAHL | = Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature |

| INS | = Infusion Nurse Society |

AVAIALABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The data supporting the findings of the article is available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13737244.