All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Stress, Depression, Anxiety, and Burnout among Healthcare Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-sectional Study in a Tertiary Centre

Abstract

Background:

Healthcare workers have been known to suffer from depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues as a result of their profession. Healthcare professionals were already vulnerable to mental health issues prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but now they are even more prone to stress and frustration.

Objective:

The study aimed to assess stress, depression, anxiety, and burnout among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, it assessed the relationship between stress, depression, anxiety, burnout, and COVID-19 related stress.

Methods:

A cross-sectional, descriptive, and correlative design was adopted to assess stress, depression, anxiety, and burnout among healthcare workers and determine the relationship among these variables during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results:

The response rate was 87.6% (831 out of 949), the majority of the participants were nurses (87.4%), and 38.4% were working in inpatient settings. The means of COVID-19 related anxiety (17.38 ± 4.95) and burnout (20.16 ± 6.33) were high and tended to be in the upper portion of the total scores. Participants reported moderate to extremely severe levels of stress (26.5%), anxiety (55.8%), and depression (37.2%). Males reported a higher level of stress (16.59 ± 10.21 vs. 13.42 ± 9.98, p = 0.002) and depression (14.97 ± 10.98 vs. 11.42 ± 10.56, p = 0.001). COVID-19 related anxiety was significantly correlated with participants’ professions (p = 0.004). Burnout (p = 0.003) and depression (p = 0.044) were significantly correlated with the participants’ working area. Significant positive correlations were found between stress, depression, anxiety, burnout, and COVID-19 related stress.

Conclusion:

Healthcare workers may experience considerable psychologic distress as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic due to providing direct patient care, quarantine, or self-isolation. Healthcare workers who were at high risk of contracting COVID-19 appeared to have psychological distress, burnout, and probably, chronic psychopathology. Frontline staff, especially nurses, were at higher risk of showing higher levels of psychological and mental health issues in the long term.

1. INTRODUCTION

In December 2019, a new viral outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, coronavirus-2 infection, occurred in Wuhan City, which later spread throughout China and other countries [1]. COVID-19 infection has shown relatively less severe pathogenesis and higher transmission competence compared to diseases caused by other formerly known human CoVs and other emerging viruses such as Avian H7N9, Ebola virus, MERS-CoV, or SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 which have shown low pathogenicity and moderate transmissibility [2]. At the end of January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel Coronavirus (nCoV), later renamed as Corona Virus Disease-2019 (COVID-19), as an epidemic of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) [3]. According to a recent study published in 2019, a MERS-CoV outbreak was expected to emerge from anywhere, at any time, and without any warning [4]. COVID-19 pandemic has affected the mental and physical health of millions of people as well as the social and economic stability of countries [5].

The direct impact of the COVID-19 on mental health service users, healthcare providers, and nurses is predicted to be a major concern and a public urgency based on previous experiences with SARS and other coronaviruses [6], which led to a public health emergency of international concern and severely influenced health system, economy, and psychology of India [7]. COVID-19 has become a disease of global concern, affecting the physical and mental health of patients as well as their lives. People who did not receive public health emergency treatment performed worse in social support, resilience, and mental health and were more likely to suffer from psychological distress and mental abnormalities such as interpersonal sensitivity and photic anxiety [8].

During the COVID-19 outbreak, healthcare workers have developed psychological problems such as depression, anxiety, stress, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and poor sleep quality [9], which, in turn, are significantly associated with physical symptoms such as headache, lethargy, fatigue, etc. [10]. Nurses, like other healthcare workers, have had psychological crises and mental health issues, necessitating hospitals to provide psychological support, train them on coping mechanisms, improve their ability to control and regulate their emotions, and provide assurance that the COVID-19 pandemic will eventually come to an end [11]. Furthermore, frontline nurses who were not trained for COVID-19 or who worked part-time reported a higher fear of COVID-19, which, in turn, was associated with increased psychological distress, decreased job satisfaction, and increased professional and organizational turnover intents [12].

According to Italian research, the COVID-19 outbreak affects effective temperament, attachment style, and person psychology, which predict the severity of mental health burden [13], as well as somatic symptoms, emotional exhaustion, and work-related psychological pressure [14]. Due to the global crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, frontline healthcare clinicians and workers have become more vulnerable to mental, psychological, emotional, and behavioral consequences while overworking to ensure the safety of their patients [15]. Iranian studies showed that healthcare workers (physicians, radiologists, technicians, nurses, etc.) had remarkable cutoff levels of depression, anxiety, and distress that varied due to demographic parameters, access to personal protective equipment, and the COVID-19 status [16], hence, their perceived threat to COVID-19 was relatively at the estimated level whereas, the perceived desired efficiency was not [17].

Burnout is a psychological syndrome caused by prolonged exposure to work or job stress [18] and it has been discovered to be more common among healthcare workers working in critical care units [19]. Burnout takes a toll on healthcare workers, leading to lower quality care and increased error rates [20]. When considering burnout, it is impossible not to reflect upon the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in daily clinical work, as well as the loss of colleagues, friends, relatives, and loved ones. Burnout is prevalent among healthcare workers taking care of COVID-19 patients [21], and they are likely to have poor work performance, absenteeism, signs of depression and anxiety, low satisfaction with work-life, and more fatigue [22]. Moreover, burnout, particularly emotional exhaustion, is significantly related to job dissatisfaction [23]. Certain variables have been studied and resulted in the association of burnout and sociodemographic qualities of healthcare workers [19], and more association has been discovered in administrative work, confrontation with sufferings, and time pressure [24]. COVID-19 pandemic has posed myriad challenges and obstacles for healthcare systems that are developing and underprepared, with healthcare workers going through more than just acute work pressure. These challenges resulted in a significant association between acute stress disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and burnout among healthcare providers especially physicians [25]. COVID-19 related burnout may lead many doctors to become disillusioned, distressed, or even more, to death of healthcare staff [26].

In Saudi Arabia, a study was conducted to explore the magnitude and determinants of burnout among nurses and physicians working at emergency departments in Abha and Khamis Mushait hospitals. It was noticed that a considerable percentage of workers reported having burnout syndrome, low personal accomplishment, high emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization [27]. In another study that aimed at assessing the perception and attitude of healthcare workers concerning COVID-19, the results showed that three-fourths of the participants felt at risk of contracting or working with the COVID-19 infection, and nearly all of them believed that the government should isolate patients with COVID-19 [28].

This study aimed at assessing stress, depression, anxiety, and burnout among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, it assessed the relationship between stress, depression, anxiety, burnout, and COVID-19 related stress.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Site/Setting

The investigators recruited participants from all health administrations at King Fahad Medical City (KFMC), Riyadh, KSA. Areas including Intensive Care Units (ICUs), Emergency Departments (EDs), Inpatient Wards, Outpatient Clinics, etc., serving COVID-19 patients were surveyed. Around 949 healthcare workers providing care for COVID-19 patients and their families were recruited.

2.2. Study Design

A cross-sectional, descriptive, and correlative study design was adopted to assess stress, depression, anxiety, and burnout among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the relationships between stress, depression, anxiety, burnout, and COVID-19 related stress were also assessed.

2.3. Study Population and Sampling

A total of 831 out of 949 participants over a period of 3 months were recruited; 726 nurses (87.6%), 35 physicians (4.2%), and 70 allied health professionals (8.4%) were recruited in our study. Inclusion criterion was all healthcare workers agreed to participate in the study. Exclusion criterion was all healthcare workers in the probationary period.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Nursing Research Committee and the Institutional Review Board at King Fahad Medical City (IRB20539). This study followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2008. Before enrollment, the researcher explained the purpose of the study and that participation in the study was voluntary. Furthermore, all participants were informed about the anonymity, confidentiality issue, and the option of voluntary termination at any time without any repercussions on their current or future work. If the participant verbally gives his consent, then he will be enrolled in the study and asked to fill out the required survey.

2.5. Sample Size Estimation

The sample size for the population survey was calculated using an online “Raosoft sample size calculator.” According to this method, a minimum of 362 participants are needed; given that the margin of error alpha (α) = 0.05, the confidence level is = 95%, total population = 6,000, and the response of distribution = 50%. Our study was able to recruit 831 participants.

2.6. Data Collection

At the time of consent, participants completed the demographic survey and the questionnaire to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers’ mental and physical conditions (stress, depression, anxiety, burnout, and COVID-19 related stress). Data was collected by the research coordinator, and data was followed up by the research assistants.

2.6.1. Demographic Data

A self-reported questionnaire was used to obtain participant’s demographics, which included gender, age, marital status, work category, professional title, area of work, years of experience in KFMC, exposure to COVID-19, testing for COVID-19, quarantined, and any family member infected with COVID-19.

COVID-19 related Stress, Burnout & DASS-21. A tool with adequate validity and reliability was used and combined three parts; two of them are international tools, namely, Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) and DAASS-21, COVID-19 related part. The first part was developed by Talaee et al. (2020) to assess the COVID-19 related stress [29]. The second part (CBI) was developed by Kristensen et al. (2005) to measure burnout [30]. The third part (DASS-21) was developed by Lovibond and Lovibond (1995) to measure depression, anxiety, and stress [31]. The questionnaire included 32 items; 5 items for COVID-19 related stress, 6 items for CBI, and 21 items for DASS-21 (7 items for depression, 7 items for anxiety, and 7 items for stress). Each questionnaire had a different measurement of Likert scale and scoring integers; COVID-19 related items were measured using a 5-point scale ranging from 0 to 4, burnout items were measured using a 5-point scale ranging from 0 to 4, and DASS-21 items were measured using a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3, then each item was multiplied by 2. A higher score of items and the total score for the questionnaire and domains indicated negative mental and physical conditions (COVID-19 related stress, depression, anxiety, stress, and burnout). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the questionnaires were: 0.953 for DASS-21, 0.942 for burnout, and 0.803 for COVID-19 related stress [29]. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.88 for COVID-19 related stress, 0.92 for CBI, and 0.96 for DASS-21. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.91, 0.87, and 0.92 for the domains of stress, anxiety, and depression in the DASS-21 questionnaire, respectively.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

IBM SPSS version 22 was used to analyze data [32]. Collected data were evaluated using descriptive statistics to examine the distribution of data values, including outliers and patterns of missing values. All nominal and ordinal data were reported in frequencies and percentages, and numerical data was reported in terms of means and standard deviations. Based on the normality of distribution, a statistical test of Pearson’s correlation was used to detect the relationships among healthcare workers’ stress, anxiety, depression, burnout, and COVID-19 related stress. Independent t-test and one-way analysis of variance (One-way ANOVA) were used to compare means of COVID-19 related stress, burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression across group demographics. All hypotheses were tested as two-sided at a significance level of P ≤ 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 shows the sociodemographics of 831 participants. The majority were females (86.2%), married (59.6%), had children (59.3%), and aged above 35 years old (45.6%). Concerning participants’ work, the majority were nurses (87.4%), working in inpatient settings (38.4%), with more than ten years of clinical experience (51.4%), and with more than one year of experience in the current clinical setting (90.5%). The majority of participants dealt with positive or confirmed COVID-19 patients (88.2%), underwent COVID-19 test (79.9%), and only 31.3% and 11.2% experienced COVID-19 associated quarantine and had a positive diagnosed COVID-19 family member, respectively.

| Variables | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 115 (13.8) |

| Female | 716 (86.2) | |

| Age | ≤ 25 | 17 (2) |

| 26 ‒ 30 | 196 (23.6) | |

| 31 ‒ 35 | 239 (28.8) | |

| ˃ 35 | 379 (45.6) | |

| Marital Status | Single | 309 (37.2) |

| Married | 495 (59.6) | |

| Widow | 11 (1.3) | |

| Divorced/Separated | 16 (1.9) | |

| Do you have children? | Not Applicable | 20 (2.4) |

| Yes | 493 (59.3) | |

| No | 318 (38.3) | |

| Work Category | Clinical | 735 (88.4) |

| Academic | 23 (2.8) | |

| Both | 73 (8.8) | |

| Professional Tittle | Nurse | 726 (87.4) |

| Physician | 35 (4.2) | |

| Allied Health Professional | 70 (8.4) | |

| Area of Work | ICUs | 146 (17.6) |

| EDs | 158 (19) | |

| Outpatient | 89 (10.7) | |

| Inpatient | 319 (38.4) | |

| ORs | 12 (1.4) | |

| Other (please specify) | 107 (12.9) | |

| Years of Experience in Healthcare Field | ≤ 5 | 150 (18.1) |

| 6 ‒ 10 | 254 (30.6) | |

| 11 ‒ 15 | 210 (25.3) | |

| ˃ 15 | 217 (26.1) | |

| Years of Experience in the current hospital | ˂ 1 | 80 (9.6) |

| 1 ‒ 5 | 338 (40.7) | |

| 6 ‒ 10 | 175 (21.1) | |

| >10 | 238 (28.7) | |

| Are you exposed to a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patient? | Yes | 733 (88.2) |

| No | 98 (11.2) | |

| Have you been tested for COVID-19? | Yes | 664 (79.9) |

| No | 162 (19.5) | |

| I'd rather not answer | 5 (0.6) | |

| Have you been quarantined? | Yes | 260 (31.3) |

| No | 565 (68) | |

| I'd rather not to answer | 6 (0.7) | |

| Does anyone of your family members have been found positive to COVID-19? | Yes | 93 (11.2) |

| No | 728 (87.6) | |

| I'd rather not to answer | 10 (1.2) | |

| Scales/Subscales | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| COVID-19 related anxiety | 17.38 ± 4.95 |

| Burnout (CBI) | 20.16 ± 6.33 |

| DASS-21 | - |

| • Stress | 13.86 ± 10.07 |

| • Anxiety | 11.93 ± 9.49 |

| • Depression | 11.92 ± 10.69 |

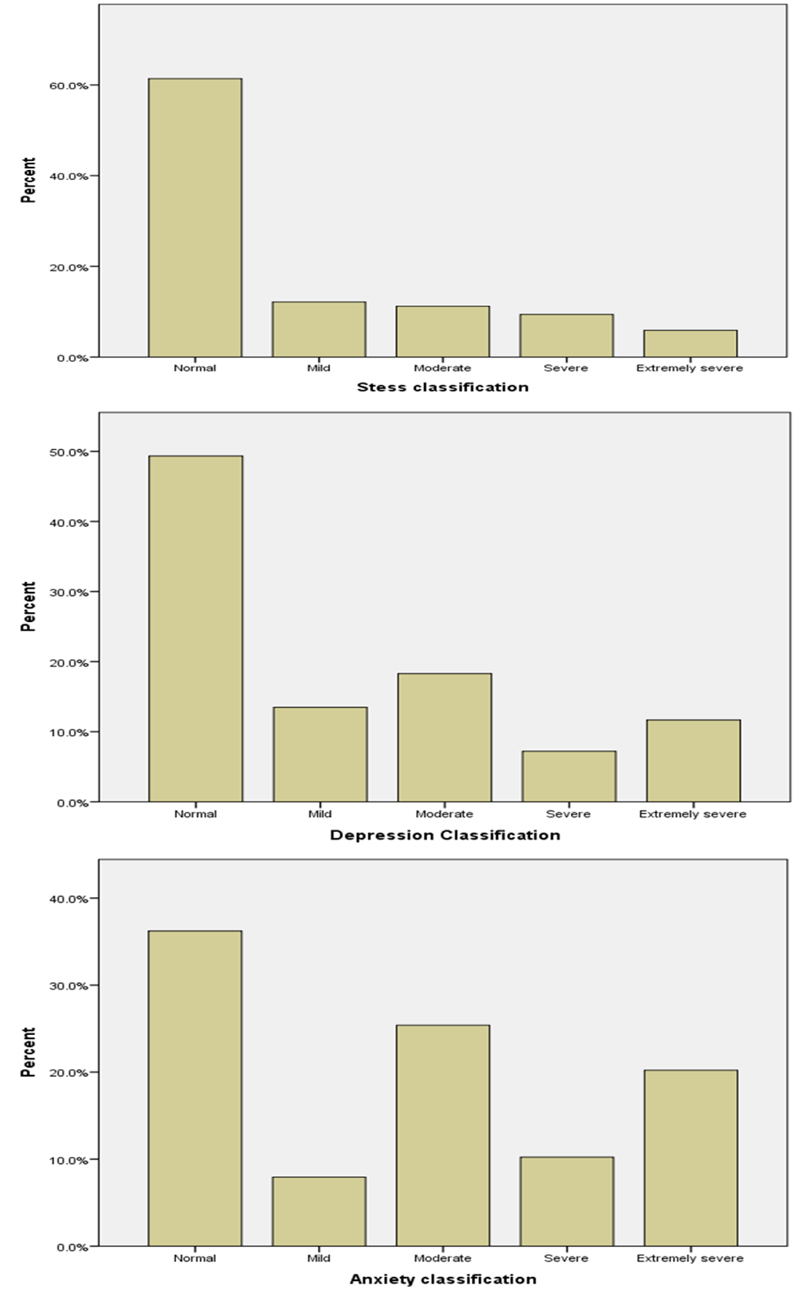

Table 2 shows participants’ averages of the total scores on the five scales. The means of COVID-19 related anxiety (17.38 ± 4.95) and burnout (20.16 ± 6.33) were high and tended to be in the upper portion of the total scores. However, the means for stress (13.86 ± 10.07), anxiety (11.93 ± 9.49), and depression (11.92 ± 10.69) on the DASS-21 seemed to be in the lower portion of their total score. Furthermore, Table 3 and Fig. (1) provide more details about the severity levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. Percentages of 26.5%, 55.8%, and 37.2% of the participants were found to have moderate to extremely severe levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, respectively.

| Variable | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Stress classification | Normal | 510 (61.4) |

| Mild | 101 (12.2) | |

| Moderate | 93 (11.2) | |

| Severe | 78 (9.4) | |

| Extremely severe | 49 (5.9) | |

| Anxiety classification | Normal | 301 (36.2) |

| Mild | 66 (7.9) | |

| Moderate | 211 (25.4) | |

| Severe | 85 (10.2) | |

| Extremely severe | 168 (20.2) | |

| Depression Classification | Normal | 410 (49.3) |

| Mild | 112 (13.5) | |

| Moderate | 152 (18.3) | |

| Severe | 60 (7.2) | |

| Extremely severe | 97 (11.7) | |

| Outcome Variables | Independent Variables | Mean ± SD | df | T value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender Male = 115 Female = 716 |

- | 829 | - | - | |

| COVID-19 related anxiety | Male | 16.97 ± 4.90 | -0.960 | 0.337 | |

| Female | 17.44 ± 4.96 | ||||

| Burnout | Male | 20.19 ± 6.30 | -0.378 | 0.705 | |

| Female | 19.95 ± 6.54 | ||||

| Stress | Male | 16.59 ± 10.21 | 3.148 | 0.002** | |

| Female | 13.42 ± 9.98 | ||||

| Anxiety | Male | 13.06 ± 10.51 | 1.374 | 0.170 | |

| Female | 11.75 ± 9.32 | ||||

| Depression | Male | 14.97 ± 10.98 | 3.326 | 0.001** | |

| Female | 11.42 ± 10.56 | - | |||

|

Marital status Single = 309 Married = 495 |

- | 802 | - | - | |

| COVID-19 related anxiety | Single | 17.66 ± 4.73 | 1.327 | 0.185 | |

| Married | 17.18 ± 5.07 | ||||

| Burnout | Single | 20.91 ± 6.28 | 2.527 | 0.012* | |

| Married | 19.75 ± 6.33 | ||||

| Stress | Single | 13.70 ± 10.56 | -0.378 | 0.706 | |

| Married | 13.98 ± 9.60 | ||||

| Anxiety | Single | 11.88 ± 9.53 | -0.076 | 0.939 | |

| Married | 11.94 ± 9.34 | ||||

| Depression | Single | 12.43 ± 11.13 | 1.118 | 0.264 | |

| Married | 11.57 ± 10.27 | ||||

|

Having children Yes = 493 No = 318 |

- | 809 | - | - | |

| COVID-19 related anxiety | Yes | 17.24 ± 5.03 | 0.907 | 0.365 | |

| No | 17.57 ± 4.82 | ||||

| Burnout | Yes | 19.58 ± 6.29 | 2.887 | 0.004** | |

| No | 20.89 ± 6.34 | ||||

| Stress | Yes | 13.57 ± 9.77 | 0.732 | 0.464 | |

| No | 14.09 ± 10.42 | ||||

| Anxiety | Yes | 11.57 ± 9.33 | 1.153 | 0.249 | |

| No | 12.35 ± 9.70 | ||||

| Depression | Yes | 11.23 ± 10.31 | 1.837 | 0.067 | |

| No | 12.63 ± 11.01 | ||||

|

Exposed to a suspected/confirmed COVID-19 patient Yes = 733 No = 98 |

- | 829 | - | - | |

| COVID-19 related anxiety | Yes | 17.52 ± 4.95 | -2.263 | 0.024* | |

| No | 16.32 ± 4.83 | ||||

| Burnout | Yes | 20.40 ± 6.36 | -3.060 | 0.002** | |

| No | 18.33 ± 5.85 | ||||

| Stress | Yes | 14.13 ± 10.11 | -2.104 | 0.036* | |

| No | 11.86 ± 9.53 | ||||

| Anxiety | Yes | 12.23 ± 9.64 | -2.470 | 0.014* | |

| No | 9.71 ± 8.04 | ||||

| Depression | Yes | 12.21 ± 10.82 | -2.156 | 0.031* | |

| No | 9.73 ± 9.38 | ||||

|

Experience Quarantine Yes = 260 No = 565 |

- | 823 | - | - | |

| COVID-19 related anxiety | Yes | 17.60 ± 4.94 | -0.919 | 0.358 | |

| No | 17.25 ± 4.97 | ||||

| Burnout | Yes | 21.19 ± 6.28 | -3.247 | 0.001** | |

| No | 19.66 ± 6.30 | ||||

| Stress | Yes | 15.55 ± 10.61 | -3.356 | 0.001** | |

| No | 13.04 ± 9.72 | ||||

| Anxiety | Yes | 13.74 ± 9.99 | -3.820 | 0.000*** | |

| No | 11.04 ± 9.16 | ||||

| Depression | Yes | 13.48 ± 11.24 | -3.012 | 0.003** | |

| No | 11.09 ± 10.30 |

*Statistically significant at (α ≤ 0.05), **statistically significant at (α ≤ 0.01), ***statistically significant at (α ≤ 0.001).

Tables 4 and 5 show the means of total scores of COVID-19 related anxiety, burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression across the participants’ sociodemographic. Compared with females, males reported a higher level of stress (16.59 ± 10.21 vs. 13.42 ± 9.98, p = 0.002) and depression (14.97 ± 10.98 vs. 11.42 ± 10.56, p = 0.001). However, males and females showed similar levels of COVID-19 related anxiety, burnout, and anxiety. Single participants’ were only different than married participants’ in terms of burnout; singles had higher levels of burnout (20.91 ± 6.28 vs. 19.75 ± 6.33, p = 0.012). Moreover, participants who did not have children had a higher level of burnout than those participants who had children (20.89 ± 6.34 vs. 19.58 ± 6.29, p = 0.004). Participants who were exposed to confirmed/suspected cases of COVID-19 were found to have significantly higher levels in all scales (COVID-19 related anxiety, burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression) than that of participants who were not exposed to confirmed/suspected COVID-19 cases (Table 4). Moreover, participants who were quarantined had higher significant levels of burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression than participants who did not quarantine (Table 4).

| Outcome Variables | Independent Variables | n | Mean ± SD | df | F value | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group/Years | - | - | 3, 827 | - | - | |

| COVID-19 related anxiety | ≤ 25 | 17 | 16.12 ± 4.08 | 2.406 | 0.066 | |

| 26 ‒ 30 | 196 | 18.16 ± 4.74 | ||||

| 31 ‒ 35 | 239 | 17.22 ± 4.87 | ||||

| ˃ 35 | 379 | 17.13 ± 5.12 | ||||

| Burnout | ≤ 25 | 17 | 19.65 ± 6.51 | 7.936 | 0.000*** | |

| 26 ‒ 30 | 196 | 21.61 ± 6.23 | ||||

| 31 ‒ 35 | 239 | 20.70 ± 6.23 | ||||

| ˃ 35 | 379 | 19.08 ± 6.27 | ||||

| Stress | ≤ 25 | 17 | 11.88 ± 8.38 | 2.850 | 0.037* | |

| 26 ‒ 30 | 196 | 15.62 ± 11.42 | ||||

| 31 ‒ 35 | 239 | 13.64 ± 9.67 | ||||

| ˃ 35 | 379 | 13.18 ± 9.55 | ||||

| Anxiety | ≤ 25 | 17 | 10.28 ± 7.42 | 3.886 | 0.009** | |

| 26 ‒ 30 | 196 | 13.94 ± 10.57 | ||||

| 31 ‒ 35 | 239 | 11.42 ± 8.82 | ||||

| ˃ 35 | 379 | 11.27 ± 9.29 | ||||

| Depression | ≤ 25 | 17 | 12.12 ± 11.72 | 4.431 | 0.004** | |

| 26 ‒ 30 | 196 | 14.10 ± 12.22 | ||||

| 31 ‒ 35 | 239 | 12.03 ± 9.99 | ||||

| ˃ 35 | 379 | 10.70 ± 10.06 | ||||

| Profession | - | - | 2, 828 | - | - | |

| COVID-19 related anxiety | Nurse | 726 | 17.59 ± 4.96 | 5.614 | 0.004** | |

| Physician | 35 | 15.43 ± 4.51 | ||||

| Allied Health Professional | 70 | 16.14 ± 4.70 | ||||

| Burnout | Nurse | 726 | 20.31 ± 6.34 | 1.855 | 0.157 | |

| Physician | 35 | 18.63 ± 6.20 | ||||

| Allied Health Professional | 70 | 19.31 ±6.25 | ||||

| Stress | Nurse | 726 | 13.60 ± 10.12 | 1.997 | 0.136 | |

| Physician | 35 | 15.77 ± 8.62 | ||||

| Allied Health Professional | 70 | 15.66 ± 10.01 | ||||

| Anxiety | Nurse | 726 | 11.99 ± 9.57 | 0.375 | 0.687 | |

| Physician | 35 | 10.57 ± 8.51 | ||||

| Allied Health Professional | 70 | 12.00 ± 9.21 | ||||

| Depression | Nurse | 726 | 11.70 ± 10.76 | 1.232 | 0.292 | |

| Physician | 35 | 13.77 ± 9.50 | ||||

| Allied Health Professional | 70 | 13.26 ± 10.44 | ||||

| Working area | - | - | 5, 825 | - | - | |

| COVID-19 related anxiety | ICUs | 146 | 17.92 ± 4.58 | 1.261 | 0.279 | |

| EDs | 158 | 17.20 ± 4.73 | ||||

| Outpatient | 89 | 17.62 ± 5.31 | ||||

| Inpatient | 319 | 17.33 ± 5.11 | ||||

| ORs | 12 | 14.58 ± 4.44 | ||||

| Other | 107 | 17.14 ± 5.01 | ||||

| Burnout | ICUs | 146 | 20.15 ± 5.98 | 3.561 | 0.003** | |

| EDs | 158 | 21.25 ± 6.34 | ||||

| Outpatient | 89 | 18.63 ± 6.98 | ||||

| Inpatient | 319 | 20.44 ± 6.08 | ||||

| ORs | 12 | 15.83 ± 6.79 | ||||

| Other | 107 | 19.44 ± 6.55 | ||||

| Stress | ICUs | 146 | 15.03 ± 9.75 | 1.812 | 0.108 | |

| EDs | 158 | 14.70 ± 10.09 | ||||

| Outpatient | 89 | 11.84 ± 11.28 | ||||

| Inpatient | 319 | 13.45 ± 9.61 | ||||

| ORs | 12 | 10.17 ± 9.96 | ||||

| Other | 107 | 14.36 ± 10.55 | ||||

| Anxiety | ICUs | 146 | 13.38 ± 9.70 | 2.071 | 0.067 | |

| EDs | 158 | 12.72 ± 10.26 | ||||

| Outpatient | 89 | 11.26 ± 10.80 | ||||

| Inpatient | 319 | 11.40 ±8.56 | ||||

| ORs | 12 | 6.33 ± 5.38 | ||||

| Other | 107 | 11.57 ± 9.65 | ||||

| Depression | ICUs | 146 | 12.79 ± 10.50 | 2.298 | 0.044* | |

| EDs | 158 | 13.23 ± 10.84 | ||||

| Outpatient | 89 | 10.83 ± 12.47 | ||||

| Inpatient | 319 | 11.39 ± 10.12 | ||||

| ORs | 12 | 4.17 ± 6.12 | ||||

| Other | 107 | 12.11 ± 10.81 | ||||

| Clinical experience/years | - | - | 3, 827 | - | - | |

| COVID-19 related anxiety | ≤ 5 | 150 | 17.66 ± 4.58 | 3.814 | 0.010* | |

| 6 ‒ 10 | 254 | 17.57 ± 5.01 | ||||

| 11 ‒ 15 | 210 | 17.72 ± 4.93 | ||||

| ˃ 15 | 217 | 16.41 ± 5.06 | ||||

| Burnout | ≤ 5 | 150 | 21.57 ± 6.23 | 9.357 | 0.000** | |

| 6 ‒ 10 | 254 | 21.02 ± 6.20 | ||||

| 11 ‒ 15 | 210 | 19.78 ± 6.20 | ||||

| ˃ 15 | 217 | 18.53 ± 6.32 | ||||

| Stress | ≤ 5 | 150 | 15.15 ± 10.73 | 2.313 | 0.075 | |

| 6 ‒ 10 | 254 | 14.39 ± 10.29 | ||||

| 11 ‒ 15 | 210 | 13.66 ± 9.81 | ||||

| ˃ 15 | 217 | 12.55 ± 9.47 | ||||

| Anxiety | ≤ 5 | 150 | 12.99 ± 9.89 | 3.667 | 0.012* | |

| 6 ‒ 10 | 254 | 12.87 ± 9.42 | ||||

| 11 ‒ 15 | 210 | 11.73 ± 9.25 | ||||

| ˃ 15 | 217 | 10.29 ± 9.36 | ||||

| Depression | ≤ 5 | 150 | 13.96 ± 11.78 | 5.056 | 0.002** | |

| 6 ‒ 10 | 254 | 12.62 ±10.39 | ||||

| 11 ‒ 15 | 210 | 11.76 ± 10.51 | ||||

| ˃ 15 | 217 | 9.82 ± 10.08 |

*Statistically significant at (α ≤ 0.05), **statistically significant at (α ≤ 0.01), ***statistically significant at (α ≤ 0.001).

Table 5 shows a one-way ANOVA for the outcomes (five scales) based on the independent variables (age categories, profession, working area, and years of clinical experience). One-way ANOVA showed that all scales with an exception for COVID-19 related anxiety were found to be significant based on the participants’ age. One-way ANOVA analysis based on the profession showed that only the levels of COVID-19 related anxiety were significantly different across the profession (17.59 ± 4.96, 15.43 ± 4.5, and 16.14 ± 4.70 for nurses, physician, and allied health professions, respectively, p = 0.004). One-way ANOVA showed that only burnout (p = 0.003) and depression (p = 0.044) were found to be significant based on the participants’ working area. Finally, one-way ANOVA showed that all scales with an exception for stress were found to be significant based on participants’ years of clinical experience. Table 6 shows one-way ANOVA Tukey's /Games Howell post hoc multiple comparisons for sociodemographic variables concerning COVID-19 related anxiety, burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression.

Table 7 shows a bivariate correlational analysis across the five scales. Significant positive correlations were found between all scales and subscales (all p values < 0.01). The highest correlation was reported between stress and depression (r = 0.901, p < 0.01), followed by the correlation between stress and anxiety levels (r = 0.858, p < 0.01). The lowest correlation was between COVID-19 related anxiety and depression (r = 0.321, p <0.01), followed by the correlation between COVID-19 related anxiety and stress levels (r = 0.348, p < 0.01).

| Outcome Variables | Pairwise Comparison | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Age group/years | - | |

| Burnout | 31-35 vs. > 35 | 0.009** |

| Stress | 26-30 vs. > 35 | 0.030* |

| Anxiety | 26-30 vs. 31-35 | 0.030* |

| 26 ‒ 30 vs. > 35 | 0.007** | |

| Depression | 26 ‒ 30 vs. > 35 | 0.005** |

| Profession | - | |

| COVID-19 related anxiety | Nurse vs. Physician | 0.031* |

| Working area | - | |

| Burnout | EDs vs. Outpatient | 0.021* |

| EDs vs. ORs | 0.047* | |

| Depression | ORs vs. ICU | 0.003** |

| ORs vs. Inpatient | 0.017* | |

| ORs vs. Other | 0.011* | |

| Clinical experiences/years | - | |

| COVID-19 related anxiety | 6-10 vs. > 15 | 0.017* |

| 11-15 vs. > 15 | 0.030* | |

| Burnout | ≤ 5 vs. 11-15 | 0.037* |

| ≤ 5 vs. > 15 | 0.000*** | |

| 6-10 vs. > 15 | 0.000*** | |

| Anxiety | ≤ 5 vs. > 15 | 0.037* |

| 6-10 vs. > 15 | 0.017* | |

| Depression | ≤ 5 vs. > 15 | 0.001** |

| 6-10 vs. > 15 | 0.023* |

*Statistically significant at (α ≤ 0.05), **statistically significant at (α ≤ 0.01), ***statistically significant at (α ≤ 0.001).

| COVID-19 related anxiety | Burnout | Stress | Anxiety | Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 related anxiety | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Burnout | 0.482** | 1 | - | - | - |

| Stress | 0.348** | 0.634** | 1 | - | - |

| Anxiety | 0.377** | 0.571** | 0.858** | 1 | - |

| Depression | 0.321** | 0.623** | 0.901** | 0.842** | 1 |

4. DISCUSSION

This is one of a few studies in Saudi Arabia that assessed stress, depression, anxiety, and burnout amongst healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The strength of this study was that it included all healthcare workers, tertiary center sampling, and larger sample size.

Healthcare workers reported moderate to extremely severe levels of psychopathologic problems; stress (mean = 17.38), anxiety mean (DASS: mean = 11.93; COVID-19 related: mean = 17.38), depression mean (11.92), burnout (mean = 20.16), supported by a similar study conducted during the outbreak of COVID-19 [33-35]. Furthermore, mental health risk factors increased, which might be due to the belief that COVID-19 is deadly, despite the fact that the global consensus is that only around 2% of cases are fatal and that it is curable [35]. Moreover, the findings revealed that due to the global tragic health crisis triggered by the outbreak of COVID-19, healthcare workers' mental health is at risk of high levels of anxiety, depression, stress, burnout, addiction, and posttraumatic stress disorder, which could have long-term psychological implications [34, 36].

The participants’ sociodemographic data showed different responses to stress, anxiety, depression, and burnout. Talking about gender, males reported higher levels of stress and depression compared to females, which confirmed a previous report of a similar study conducted in China [37, 38]; both reported similar experiences of COVID-19 related psychopathology, which is, however, in a similar study conducted in Italy, women reported higher levels compared to men [39]. These differences could be related to other factors such as mental health training, previous experiences, and a strong social support network [40].

Our study suggests that age, particularly between 26-30 years, was significantly related to psychological distresses; burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression. Similar findings were reported by other studies [38, 41]. In addition, another study found a similar result when it came to whether or not to have children. Another factor linked to higher burnout is having a dependent family (spouse and children) [41].

Healthcare professionals are obliged to provide the necessary care, therefore, exposure to COVID-19 patients, whether suspected or diagnosed, is inevitable. Hence, fear of being infected, transmitting the virus to their families and children, and losing their loved ones are significant contributing factors to higher levels of stress, depression, anxiety, and burnout in healthcare workers [38, 42-44]. According to the findings of this study, participants with confirmed/suspected cases had significantly greater levels of COVID-19-related anxiety, burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression. Moreover, self-isolation and quarantine were reported to be associated with considerably higher levels of psychological distress and short-term and long-term mental health problems [41, 45, 46]. Such findings were in concordance with our study; those who experienced quarantine were reported with higher significant levels of burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression than those who did not undergo quarantine.

This study shows that only COVID-19 related anxiety differs based on the profession. Nurses reported higher levels of COVID-19 related anxiety than other professions. Studies reported the profession to be an influential risk factor significantly correlated with high levels of psychopathologic and mental health distress [47, 48]. As a major syndrome resulting from job stress, burnout was significantly associated with variation in workload, intragroup conflict, skill underutilization, and job dissatisfaction [49].

Frontline healthcare workers who directly diagnose, treat, and care for COVID-19 patients, particularly nurses in emergency and critical care settings, reported higher levels of burnout, psychological burden, and COVID-19-related psychopathology [39, 48-50]. Non-frontline healthcare workers, on the other hand, showed greater levels of depression and burnout than during the COVID-19 outbreak, leading to vicarious traumatization [51]. Such findings were supported by our study since burnouts were found to be significantly different based on the working area. The highest levels of burnout were reported by participants working in the emergency department.

Clinical experience plays a vital role in responding to outbreaks and disasters. In our study, the participants’ clinical experience was significantly correlated with COVID-19 related anxiety, burnout, anxiety, and depression. Similar findings were reported by another study [38]. This explains that lack of previous experience, knowledge, training, and education lead to poor response and application of precautionary and preventive measures of COVID-19 and to psychopathology and mental health problems [52].

This study found positive correlations between all studied variables: COVID-19 related anxiety, burnout, stress, anxiety, and depression. Our study was in concordance with earlier studies [38].

5. LIMITATIONS

The study has some limitations, such as the single-site study, the fact that physicians and allied health professionals participated in lower numbers than expected while nurses participated in higher numbers, and the fact that some participants did not experience the pandemic and participated immediately after job commencement or the vacation. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design precludes causation.

CONCLUSION

The global crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic fostered fear among healthcare workers who were concerned for the well-being of their co-workers, families, friends, communities, and countries [53]. It has a certain psychosocial impact upon healthcare workers, such as psychological distress, physical and psychological symptoms, and short-and long-term mental health problems. Having a dependent family (spouse and/or children), an infected family member, quarantine, and exposure to a suspected or confirmed infected patient were identified by participants as factors associated with high levels of psychological distress and burnout. Globally, burnout is more strongly related to job satisfaction than general health [54].

Stress, depression, anxiety, and burnout were found to be risk factors influencing healthcare workers’ performance. Cognitive, physiological, and behavioral effects of stress and burnout on the individual present a state in which healthcare workers cannot perform efficiently. This means that the impact of stress, depression, anxiety, and burnout are negative and a threat to productivity [55].

RECOMMENDATIONS

Efforts and measures should be undertaken to reduce job-related stress and burnout during the emergence of contagious diseases. Furthermore, administrative, psychological, and emotional support during pandemic disease should be ensured, as should stress management programs and hospital resources for the treatment of corona diseases [56]. Furthermore, universal evidence suggests adopting multipronged evidence-based strategies to address burnout [57], such as Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) [17]; hence, efforts should be made to reduce stress and burnout by promoting and enhancing positive coping strategies and mechanisms based on previous experiences that successfully enhanced resilience against pandemic [15].

Effective measures, such as strengthening protection, training adequate nurses for emergency and fever clinics, reducing night shifts, and timely update of the latest epidemic situations, should be taken. Strong leadership with clear, honest, and open communication is needed to offset fears and uncertainties. Individual self-efficacy and confidence will be bolstered by the provision of adequate resources (e.g., medical supplies) and mental health assistance. Risks associated with psychological stress in the workplace can only be identified and mitigated by a collaborative effort [58].

IMPLICATIONS FOR ORGANIZATION MANAGEMENT

Healthcare leaders should pay attention to the job stress and variables that affect healthcare professionals combating COVID-19 infections and provide solutions that can help these employees retain their mental health. Stressed, depressed, anxious, and burnout healthcare workers will not be able to function optimally because of the cognitive, physiological, and behavioral challenges they have to deal with. When healthcare employees quit, the expenses of replacement as well as the onerous duty on the existing staff are overwhelming. Healthcare organizations are requested to monitor the psychological stress levels of healthcare workers and introduce plans to reduce or eradicate the negative impacts of these consequences.

Health organizations are responsible for providing a system that adapts to and embraces healthcare professionals during and after calamities [59]. Abbreviated Mindfulness Intervention (AMI) training is assessed to be a time-efficient tool associated with reducing job burnout, anxiety, stress, and depression. Moreover, it promotes clinician health and well-being, which may positively impact patient care [60].

Failure to address mental conditions and respond to those conditions will ultimately lead to ominous consequences, such as shorter job tenure, increased workload, work-related stress, social detachment, etc. The risk of being infected, burnout, and perceived risk of personal fatality from the pandemic are predictors for tendering resignations, or even more, extending to suicide and psychiatric diseases amongst healthcare workers, which will seriously cast a shadow over the healthcare organizations.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Jaber contributed in writing the study's concept and design. The literature review and article analysis were carried out by Alqudah. Al-Bashaireh helped with the methods, data extraction, and analysis, as well as writing the results section and editing the final version of the manuscript. AlTmaizy assisted in writing the paper and data collection. Du Preez submitted the IRB approval from the Nursing Research Committee and KFMC Research Center and communicated with the participants before collecting the data. AlShatarat & Abu Dawass prepared the electronic version of the questionnaire, distributed it, and collected the data. AlGhamdi assisted in writing the discussion, results, and editing the final manuscript. AlBashaireh, Alqudah, and Jaber edited and approved the final manuscript.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the Nursing Research Committee and the Institutional Review Board at King Fahad Medical City (IRB20539).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals/humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Furthermore, all participants were informed about the anonymity, confidentiality issue, and the option of voluntary termination at any time without any repercussions on their current or future work. If the participant verbally gives his consent, he will be enrolled in the study and asked to fill out the required survey.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

STROBE guildline and methodologies were followed in this study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

FUNDING

This study was funded by the author (no fund granted by any other party). The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of King Fahad Medical City.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.