All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Factors Hampering the Participation of Nursing Staff in the Continuing Education Activities of Hospitals Centers in the Casablanca-Settat Region

Abstract

Aim:

This study aimed to identify the factors hampering the participation of nurses in the activities of CE sessions at the level of hospitals in the region of Casablanca.

Background:

Continuing education (CE) for nursing staff represents a strategic asset for hospitals, identifying the constraints of nursing staff participation in continuing training could help improve the quality of care for patients and the population in general.

Objective:

This study aimed to identify the factors hampering the participation of nurses in the activities of CE sessions at the level of hospitals in the region of Casablanca.

Methods:

The study used a two-phase mixed method design. First of all, a questionnaire was administered to 930 nurses belonging to 9 hospital centers in the Casablanca-Settat region in order to explore and estimate the frequencies of the factors hindering the participation of nurses in the activities of the FC sessions at the level of hospitals, and a semi-structured interview with 9 persons in charge of continuing education from these different hospitals to complete and explain the data collected by the questionnaire.

Results:

The data analysis confirmed that the work overload is the first individual difficulty hindering the participation of nurses in CE sessions, i.e., 85.4%. The most mentioned organizational difficulties are schedule recommended in the FC not encouraging and not suitable, i.e., 23%, non-targeted content (does not meet the needs of the nursing staff), i.e., 66.7%. Finally, the absence of support measures in terms of monitoring and evaluation to maintain the knowledge and skills acquired during FC sessions in real situations at the workstation occupied is the first institutional difficulty mentioned by the interviewed (88%).

Conclusion:

Those responsible for training should take into account the factors nurse’s face in participating in continuing education sessions when designing, developing, and implementing continuing education sessions.

1. INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, continuing education (CE) for nurses is a necessity in the face of scientific and technological developments, which requires the acquisition of new knowledge, the development of other skills, as well as the renewal of clinical practices [1]. Research has demonstrated its purpose and usefulness in the acquisition of knowledge, improvement of care, and, consequently, improvement of patient service [2-4].

On that basis, continuing education must, above all, respond to the desire of health professionals to maintain and improve their professional qualifications and respond to the exigencies of the health system, which, in turn, must correspond to the health needs of the population [2].

Continuing education activities have become a tangible source of motivation for nurses [5-7]. For this reason, they play a very important, significant, and relevant role in the development of the individual and collective skills of the health professional by responding to the evolution and development of their abilities [1, 6, 7].

In effect, the majority of researchers recommend that every nurse should participate in continuing education sessions to constantly learn to be able to respond to the incessant needs of the society.

However, the implementation of continuing education activities for health professionals faces many constraints, including organizational difficulties, personal difficulties in terms of availability, and financial difficulties [8, 9], resulting in low participation of nurses in continuing education initiatives in different countries [1, 5, 6]. In this sense, there are few studies on continuing education in nursing and few that address the factors that may be behind this finding.

In this context, some researchers have suggested that the main factors hindering nurses' participation can be linked mainly to individual, contextual and organizational factors [10], while other researchers have distinguished other variables related to the learner, teacher, educational process, and finally erroneous evaluations at the end of the training [11].

Furthermore, in Morocco, continuing education is considered a right for all nurses and a duty for the administration [12]. Continuing education programs for nurses are managed and financed by the Ministry of Health or autonomous hospitals according to ministerial norms and standards, starting with diagnosis and ending with evaluation [13]. However, no regulations are specifying the conditions and requirements for continuing education for nurses.

At the level of different prefectural or provincial Hospital Centers (HCs) in the Casablanca-Settat region, training programs are decided annually for the benefit of nursing staff according to the strategic orientations of the Ministry of health. An average of 10 training sessions is organized each year. Moreover, the beneficiaries are called before the training. We have also observed that the majority of the proposed continuing education courses are voluntary; they are not compulsory, and often general rather than specific. These training are often linked to the institutional needs rather than the nursing staff.

Based on the experiences of our nurses in the field, and according to the interviews with some of the people in charge of continuing education of the said hospitals, we can predict that the continuing education mentioned in different hospitals, especially in its face-to-face approaches, remains limited and less planned and does not reach the desired rate of achievements: these realities observed in the field are justified by a participation rate of the beneficiaries that hardly exceeds an average of 59% of the people invited during the last three years. This rate varies among different hospital centers. The lowest participation rate is 36% in the HCs, where they are marked by an absence of people responsible for continuing education.

Through this observation and this study, we propose to describe the factors that slow down the participation of nurses in continuing education sessions. It is important to better understand the origin of this phenomenon, as it will have an important influence on the quality of care provided to the patient.

The objective of this study is to identify the factors hindering nurses' participation in CE session activities in the different hospitals of the Casablanca-Settat region. In other terms, we will try to find answers to the non-participation of the nursing staff in the activities of the continuing education sessions in the different hospitals that are able to update their knowledge and promote the development of their technical skills for the improvement of the quality of the patient care.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Continuing Professional Development (CPD) for nurses has been a topic of discussion and debate for many years. However, only a few studies have examined this variable in the care setting among nurses.

We will first deal with a definition of the concept of continuing education in nursing science, followed by an in-depth description of the research work carried out in this field of study in the context of continuing professional education of health personnel. The last part of the contribution will be devoted to the formulation of concrete proposals for the improvement of continuing education, research, and nursing practice.

Of course, we will limit the context of our research to continuing education organized within hospitals, knowing at first sight that the majority of continuing education offered is voluntary and not mandatory.

2.1. Continuing Professional Development: A Lever for Continuous Professional Development

According to literature reviews, the concept of continuing education refers to training activities that take place after the completion of initial training. It promotes the enrichment and updation of knowledge and the development of skills [14].

As a corollary, Abbatt & Mejia stated “Continuing education encompasses all forms of learning, not just refresher courses, and extends from the end of initial training to retirement. It covers not only knowledge but also a wide range of skills that are directly relevant to the delivery of health care” [2].

There are several reasons for the need for continuing education among nurses. On the one hand, research shows that the knowledge acquired in basic professional education has a half-life of about 2.5 years, and by the end of this period, the knowledge that is not reinforced by continuing education will be outdated or obsolete [15, 16].

On the other hand, this education will expire 5 years after graduation, so the lack of continuing education can lead to a deterioration of services to patients or even their death [16]. The updated CE curriculum can provide nurses with the knowledge and skills that they will need throughout their professional lives [1].

Therefore, it is important to update the knowledge and skills of nurses through continuing education to ensure safe and competent care for the population [15-19].

2.2. Continuing Education in Nursing: A Right and an Obligation

The rapid and constant evolution of knowledge requires nurses to continuously update their knowledge throughout their scareers, through continuing professional education. In this respect, in the Quebec context, CE has become an ethical obligation requiring nurses to participate in a minimum of 20 hours of continuing education activities annually to maintain their right to practice [1-19].

The nurse has a legal responsibility to keep his or her specific knowledge and skills up to date in terms of the care provided [20, 21].

For its part, the health care institution is obliged to keep the knowledge of its health care personnel up to date by implementing continuing education programs [22]. These programs must include monthly training sessions, annual theme days and should cover one or more aspects related to the advanced specialties of the units concerned [2].

On this basis, continuing nursing education is recognized as a right of all health professionals, regardless of their mode of practice, and a duty of the health institution to which they are attached [17-22]. It is recommended that such an education program should be flexible and related to the specific needs of nurses [2].

2.3. Factors Hindering the Participation of Nurses in the Continuing Education Session

Continuing education helps nurses to keep their practice safe and current. Although the literature emphasizes the need to update knowledge and skills and outlines information on motivational strategies and learning styles, little research has been done on the barriers to nurses' participation in continuing education. Certainly, this literature review describes factors that constrain nurses' learning and participation in continuing education activities.

Gibson attributed this finding to several factors, the most important of which were related to work overload, which also negatively influenced nurses' professional development. Other constraining factors noted were related to the lack of time and resistance to change for participation in continuing education activity [23].

However, Santos reported that some of the factors constraining nurses' learning are:(a) the lack of time and inflexible work schedules, (b) organizational culture that encompasses lack of support from managers and colleagues, inability to apply new knowledge in practice, and the risk of being judged by colleagues, and (c) training that are held distant from the workplace and not necessarily adapted to nurses' needs [24].

More recently, and in view of other studies interested in continuing nursing education, the attitude was mentioned as a central theme due to which nurses participated in a continuing professional development program [9-26].

In order of importance, the four priorities that influenced this attitude were communication, continuing professional development, time constraints, and financial implications [26].

In accordance with the studies conducted by Shahhosseini & Hamzehgardeshi, it was proposed that the mean score of facilitators for nurses' participation in continuing education was significantly higher than the mean score of barriers.

Moreover, the highest mean score among the facilitators of nurses' participation in continuing education was related to “Update my knowledge”. In addition, the highest mean barrier score from the participants' perspective, in three personal, interpersonal, and structural domains, was related to “time constraints”, “lack of support from colleagues” and “professional commitments” [16].

On another niche, Eslamian, Moeini & Soleimani showed that the current approach to nurse CE needs to be changed to meet their needs. Therefore, education management and planning should be based on a new approach that focuses on nurses' needs.

In addition, attention should be paid to problems related to inadequate facilities and faulty assessments during CE sessions. In other words, nurses' practice should be supervised after training to determine whether or not the educational objectives have been met [11].

In contrast, in a literature review, Gopee mentions important aspects of the factors facilitating lifelong learning according to the following categories: individual (or personal), organizational and socio-political [9].

The individual or personal factors that have been highlighted by both Gopee and Timmermans et al. show that there is a relationship between positive attitude towards learning in the workplace, whether in groups or individually, an appreciation of teamwork, and an interest in continuous improvement [9-25].

Thus, workplace learning is a major challenge for healthcare organizations, which cite staff shortages, the time required for training, and budgetary constraints as factors that make workplace professional development more complex [27].

However, organizational factors that facilitate nurses' participation in continuing education programs mentioned Gopee are the requirement for continuing education hours by professional bodies, budget allocated to continuing education, time off available for those who engage in continuing education activities, career development opportunities, on-the-job learning and changes in teaching methods [9].

Similarly, the institutional factors discussed Gopee are learning organization, managers focused on clinical supervision, reflective practice, and peer review as strategies to maintain competencies. At the societal and governmental level, factors are related to favorable attitudes towards training, budget allocation, and promotion of training through policies that influence development [9].

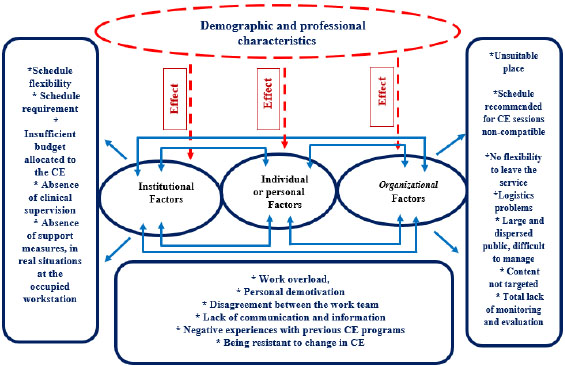

2.4. Framework

The analysis of the literature has enabled us to construct our conceptual frame of reference (Fig. 1). This conceptual framework constitutes a schematic representation of the factors hindering the participation of nurses in CE sessions, which in turn groups together three sub-difficulties, individual (or personal), organizational and institutional. Arrows illustrate the factors that can affect each other. However, some of the components of these difficulties could be either placed in one set of groups or several groups.

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Study Environment

The study was conducted at nine prefectural or provincial Hospital Centers (HCs) in the Casablanca-Settat region during March, April, and May 2018.

3.2. Target Audience and Sample

A random selection was made of the various prefectural or provincial hospitals in the Casablanca-Settat region out of the 15 hospitals; (N: 1462 nurses) and some criteria were established, namely bed capacity, specialty, geographical area, population served, and reference level. Subsequently, after the random selection of nine hospitals, the study involved all nurses practicing and providing care, therefore, cluster probability sampling technique was used. The sample size was set at (n1: 1115) (i.e., 76.26% of the total population).

The data collected will be supplemented by nine semi-structured interviews (n2:09) with those responsible for continuing education. Thus, the target population will consist of two categories:

n1: the nursing staff;

n2: those responsible for continuing education

The target population is therefore:

n= (n 1 + n 2 ) = 1115+09=1124

3.3. Data Collection Methods

Given the nature of this study, which aims to describe information on the factors hindering nurses' participation in continuing education sessions, a questionnaire was found to be useful. For this purpose, the questionnaire was developed mainly based on the models proposed by Gopee (2005), Milhomme & Gagnon (2010), Hamzehgardeshi & Shahhosseini, (2014), and by Eslamian et al. on facilitating and hindering factors of continuing education in nursing. These models posit several determinants that may have a significantly positive or negative influence on adherence to continuing education sessions [9-11, 16]. The questionnaire was distributed by the principal author of this study to n1 =1115 participants from the different HPCs. The sample that answered the questionnaire consisted of 930 participants (83.40%).

The questionnaire was constructed according to the steps described by Fortin [28]. The questions were formulated in such a way as to respect the conceptual frame of reference of the study. To this end, the questionnaire is composed of two principal parts:

(a) The first part aims to find out the general characteristics of the respondents (age, sex, seniority in the service, seniority in the profession).

(b) The second part is composed of several questions related to different factors hindering nurses' participation in continuing education sessions, as identified in the frame of reference of this study. These factors are (a) individual (or personal), (b) organizational, and (c) institutional.

The questionnaire contained (a) closed multiple-choice or semi-open questions. According to Fortin, these types of questions are simple to use and easy to code and analyze, and (b) a few open-ended questions with free responses. The questions are arranged so that the closed-ended questions precede the open-ended ones [28].

The questionnaire was examined before use by a group of experts, who were not involved in the study, and a pre-test was carried out with nurses with the same characteristics as the population under study, who were not part of the sample to judge the relevance of the questions, their degree of comprehension and their ability to provide the required information. This pre-test also allowed us to estimate the time required to complete the questionnaire. Indeed, we can admit that the construct validity of the administered questionnaire could be considered as established.

For the reliability of the questionnaire, we carried out tests and pre-tests with a panel of nurses, having 15 participants. The results obtained showed stability of 91.3%.

The principal author of this study conducted semi-structured interviews with those responsible for continuing education in the various hospitals, based primarily on the theoretical model of the Continuing Education Standards cycle proposed and adopted by the Moroccan Ministry of Health in 1990. This cycle contains five essential steps, namely:

- Diagnosis of Performance,

- Planning,

- Programming,

- Execution,

- Monitoring and evaluation

In this cycle, CE activities are planned logically and sequentially in which the authors describe the elements of educational activity as part of a “system”. The interest of this interview lies in the completion and explaination of the data collected through the questionnaire and also to obtain their point of view on the course of the training session and to share possible suggestions to enhance the participation of nurses in CE sessions. In our interviews, we evaluated the variables mentioned above following our reference model.

We used direct contact with the interviewees. Before interviewing them, information about the aims of the study was established, consent was obtained and permission to take notes or record the interviews was obtained. The continuing education manager interview guide was tested with those responsible for continuing education in hospitals with the same characteristics as the study settings. It consists of four distinct parts:

- Personalized identification of the responsible for CE: gender, age, grade, profile, function, seniority, place of work;

- Variables related to the pedagogical process: identification of needs, planning, programming, execution, monitoring, and evaluation;

- Variables related to the factors hindering nurses' participation in CE sessions;

- Two open-ended questions were included to generate suggestions and recommendations that could contribute to improving nurses' participation in CE sessions.

In effect, these interviews helped to complete and explain the data collected by the questionnaire. The time interval for each interview was scheduled between 20 and 30 minutes.

3.4. Data Collection Process

The data collection process was spread over two phases:

(a) The first concerned the questionnaires for the nursing staff that was spread out during March, April, and May of the year 2018.

(b) The second phase involved nine semi-structured interviews with those responsible for continuing education. These interviews were conducted during May.

3.5. Data Analysis Method

The treatment of the data related to the questionnaire is based on the description of the frequencies and percentages of the different categories covered by the variables of the study. The association between the demographic and professional data and the individual, organizational and institutional factors was tested with a Chi-square analysis (p < 0.05). For this purpose, data were entered into an Excel file and then analyzed using SPSS statistical software. The results were presented in tabular form to visualize frequencies and percentages.

For the interview data, a thematic content analysis was performed (Fortin, 1996) which consists of:

- Gathering data on all the themes put forward by the participants;

- Identifying categories of this content;

- For each item, the principal idea is raised and sometimes faithfully transcribed in the form of verbatim;

- Grouping and classifying the information to complete the data from the questionnaire.

| Characteristics | Staffing n1 (n1 = 930) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 405 | 43.5 |

| Female | 525 | 56.5 |

| Age | ||

| 20-30 | 192 | 20.6 |

| 31-40 | 252 | 27.1 |

| 41-50 | 267 | 28.7 |

| 51-59 | 219 | 23.5 |

| Seniority in the service | ||

| 6 months to 1 year | 59 | 6.3 |

| 1 to 5 years | 189 | 20.3 |

| 5 to 10 years | 211 | 22.7 |

| More than 10 years | 471 | 50.6 |

| Seniority in the profession | ||

| 6 months to 1 year | 4 | 0.4 |

| 1 to 5 years | 233 | 25.1 |

| 5 to 10 years | 271 | 29.1 |

| More than 10 years | 422 | 45.4 |

3.6. Ethical Considerations

The study was carried out after the approval of the directors of the various hospital centers in the Casablanca-Settat region. Participants' consent was also obtained. They were reassured that their answers would remain confidential and their identities would not be revealed in research reports and publications.

4. PRINCIPLE RESULTS

4.1. Quantitative Study Results

4.1.1. Demographic and Professional Characteristics of the Sample

Nine hundred and thirty (930) nurses out of one thousand one hundred and fifteen (1115) responded to the questionnaire, i.e., a response rate of 83.40%. The general characteristics of the respondents were marked by a slight predominance of women (525,i.e., 56.5%) and 405 men (43.5%).

The most dominant age group was between 41-50 years (28.7%).

We note that the most dominant seniority in the profession is more than 10 years,i.e., 45.4%, which shows a certain maturity reinforced by seniority in performing their duties. However, the evolution of the nursing profession requires new skills and a new vision.

We note that the most dominant seniority in the service is more than 10 years, i.e., 50.6% (Table 1).

4.1.2. Factors Hindering Nurses' Participation in CE Session Activities

● 85.4% of the interviewees stated that work overload is the first personal difficulty hindering nurses' participation in continuing education sessions.

● The organizational difficulty mostly mentioned by the interviewees is the non-targeted content (content that does not meet the needs of nurses, i.e., 66.7%.

● The main institutional difficulty hindering the participation of nurses in CE sessions is the absence of accompanying measures, in terms of follow-up and evaluation, to maintain the knowledge and skills acquired during CE sessions in real situations at the work station occupied.

4.2. Effect of Gender

The analysis of the statistical data indicates that gender has a significant effect on the organizational factors with a p = 0.000 (in a proportion of 50% of the participants).

However, there was an absence of a statistically significant relationship between gender and the different variables of individual and institutional factors (with a p = 0.05) (Table 2).

4.3. Effect of Age

The analysis of the statistical data indicates the presence of a statistically significant relationship between age and all the individual (or personal), organizational and institutional factors with a p = 0.000 (respectively in a proportion of 40%, 50% and 56% of the interviewees) (Table 3).

Therefore, it can be concluded that age has a significant effect on the different factors hindering the participation of nurses in continuing education sessions with a p < 0.05.

Table 2.

| Variables /Frequencies | n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

|

Individual (or personal) Factors |

Overload of work | 794 (85.4%) |

136 (14.6%) |

| Personal demotivation | 384 (41.3%) |

546 (58.7%) |

|

| Disagreement between the work team | 430 (46.2%) |

500 (53.8%) |

|

| Lack of communication and information | 351 (37.7% |

579 (62.3%) |

|

| Negative experiences with previous CE programs | 197 (21.2%) |

733 (78.8%) |

|

| Being resistant to change | 47 (5.1%) |

883 (94.9%) |

|

| Organizational Factors | Unsuitable location | 443 (47.6%) |

487 (52.4%) |

| Non-supportive and non-compatible CE time schedule | 511 (54.9%) |

419 (45.1%) | |

| No flexibility to leave the service | 340 (36.6%) |

590 (63.4%) | |

| Logistical problems related to the organization | 406 (43.7%) |

524 (56.3%) | |

| Large and dispersed audience, difficult to manage | 321 (34.5%) |

609 (65.5%) | |

| Content not targeted | 620 (66.7%) | 309 (33.3%) | |

| Total lack of follow-up and evaluation of training sessions | 607 (65.3%) | 323 (34.7%) | |

| Institutionnal Factors | Flexibility of time to attend CE | 318 (34.2%) | 612 (65.8%) |

| Scheduling requirement to attend CE | 531 (57.1%) | 399 (42.9%) | |

| Lack of clinical supervision | 808 (86.9%) | 122 (13.1%) | |

| Lack of accompanying measures | 818 (88%) | 112 (12%) |

|

| Insufficient budget for continuing education | 146 (15.7%) | 784 (62.2%) |

|

| Factors/ Effect |

Individual (or personal) Factors |

Organisationnel Factors |

Institutional Factors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | > 0.05 | 0.000 | > 0.05 |

| Female | ||||

| Age | 20-30 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 31-40 | ||||

| 41-50 | ||||

| 51-59 | ||||

| Effect of seniority in the service (P) |

6 months to 1 year |

0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 1 to 5 years |

||||

| 5 to 10 years |

||||

| More than 10 years |

||||

| Effect of seniority in the profession (P) | 6 months to 1 year | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 1 to 5 years |

||||

| 5 to 10 years |

||||

| More than 10 years |

||||

4.4. Effect of Seniority in the Profession

The analysis of the statistical data indicates the presence of a statistically significant relationship between seniority in the profession and all the individual (or personal), organizational and institutional factors with a p = 0.000 (respectively for a proportion of 40%, 50% and 56% of the participants).

We can, therefore, conclude that seniority in the profession has a significant effect on the factors hindering nurses' participation in continuing education sessions with a p < 0.05.

4.5. Effect of Seniority in the Service

The analysis of the statistical data shows the presence of a statistically significant relationship between seniority in the service and all the individual (or personal), organizational and institutional factors with a p = 0.000 (respectively in a proportion of 40%, 50% and 56% of the participants). We can, therefore, conclude that seniority in the service has a significant effect on the factors hindering nurses' participation in continuing education sessions with a p < 0.05.

4.6. Qualitative Study Result

Content analysis of the qualitative data collected from those responsible for continuing education identifies factors inherent in nurses' non-participation in continuing education sessions.

4.7. Item I: Diagnosis of Performance

The interviewees stated that a structure is followed for carrying out all the steps of the CE standards cycle, from the determination of the needs of nurses in CE to the follow-up and evaluation of CE activities.

At the beginning of the interview, one of the interviewees stated his positive perception of the Needs Analysis Identification by relating to “the needs analysis is a primordial step to ensure the planning of continuing education. However, “this step of diagnosing the problem and identifying training needs, as described by the 1999 National Continuing Education Standards, has been skipped.”

Also, another interviewee revealed that “the training needs analysis is perhaps the most important function of a C.T. system. Without a needs analysis, there is no way to know if C.T. is relevant or useful.”

Another interviewee added that “ministerial instructions and new developments in health programs constitute an overlap of activities that prevent a precise focus on the real CE needs of nurses, and as a result, we are forced to apply CE sessions that respond to strategically established institutional needs and not to the needs felt and declared by the health professional.”

4.8. Item II: Planning and Programming

Various interviewees (5/9) reported that “planning and programming are essential steps in the CE cycle, which should normally be carried out in collaboration with the different actors.”

Also, the interviewees were unanimous in stating that “the planned and programmed CEsessions are not carried out because of the deficiencies noted at the various stages of the process about weaknesses at the organizational level, in terms of lack of human, material and financial resources and the absence of identification of actual needs before the development of CE action plans.”

In addition to this, there were problems related to the teaching methods and materials, and the methodologies adopted were not attractive, therefore, the transfer of skills after the training sessions was insufficient.

Similarly, an interviewee stated that “a large number of programmed sessions were not preceded by the setting of objectives to be achieved, which makes the realization of these sessions difficult, sometimes impossible, and the monitoring and evaluation of skills and performance non-existent.” In such a context, it becomes difficult to obtain a measure of the impact of training activities on those who participate in them and on the organization that initiates them.

4.9. Item III: Execution

Various interviewees (5/9) mentioned that “execution is also the most significant step to reach the objectives of the CE. However, the scarcity of means is an obstacle to the realization of the programmed sessions.” According to the interviewees, these obstacles are related to the lack of coordination of the different actors between all the stages of the process of carrying out CE sessions, the problem of financing CE activities initiated at the local level, the absence of documentation units and the lack of continuing education in pedagogy and andragogy for the trainers.

One of the most striking words of an interviewee was “even we, as responsible forCE,must have training in the engineering and management of the CE cycle in order for CE activities to be successful.”

4.10. Item IV: Monitoring and Evaluation

The interviewees were unanimous in stating that “monitoring and evaluation initiatives are still rare in order to measure the gap between the sessions that were scheduled and those that were carried out. Evaluation is necessary in order to have benchmarks on the approach used during the programming and execution of CE sessions, as well as on the means used in order to take corrective measures.”

One of the interviewees stated that “there is a total absence of evaluation during and after continuing education. Conducting a continuing education evaluation is not always considered due to lack of time. As a result, the evaluation of all the stages has never been done, which highlights the importance of this stage in order to identify constraints and correct them.”

In the same perspective, the different interviewees put forward another factor of primary importance, which is the lack of regulations governing the continuing education of nurses.

On this point, another interviewee announced “that in addition to the absence of a regulatory basis, there is even a legal vacuum to encourage health professionals to participate in CE sessions; based on this observation, the presence of personnel is not mandatory due to the lack of a regulatory provision requiring them to attend CE sessions”

Indeed, those responsible for education suggest that “first of all, a revision of the methodology used for the diagnosis of continuing education needs indicate that a legal basis should be provided for the continuing education of health professionals,” the institutionalization of CE is a guarantee of commitment in all CE sessions. It is also important to make sure that the available pedagogical materials are adapted according to the training needs and the public. Also, there is a need to ensure an accompaniment and a follow-up and evaluation for all the stages of the cycle of the continuous training.

Finally, there is a need to rely more on modern strategies and technologies, especially e-learning platforms. Indeed, the implementation of these proposals remains essential to ensure the participation of nurses in CE sessions in hospitals.

5. DISCUSSION

This work is part of a reflection to improve the participation of nurses in CE sessions to ensure both the updation of their knowledge and the development of their technical skills to consequently improve the quality of patient care.

However, the results of the exploratory qualitative interviews conclude that there are many factors preventing nurses from participating in the CE activities scheduled by the trainers at the HPC level.

According to the trainers, these factors are inherent to the lack of identification of actual needs before the development of the CE action plans, especially in the performance diagnosis stage. This is in addition to the inadequacy of the resources (human, material, and financial) allocated to training in the planning and programming stage.

Similarly, the results suggest a total absence of monitoring and evaluation during and after the continuing education stage, and finally, a regulatory failure due to the absence of regulatory texts governing the continuing education of nurses. Our results seem to correspond perfectly to the conclusions drawn from the conceptual model adopted.

Also, the results of the questionnaire showed that nine hundred and thirty (930) nurses responded to the questionnaire, a response rate of 83.40%. This participation rate is considered relatively high and could be explained in part by the interest in continuing education for nurses.

The study also reveals the existence of a statistically significant relationship between demographic and professional characteristics (age, seniority in the profession, and seniority in the department) with the different variables of individual, organizational and institutional difficulties. However, the results also reveal the absence of a statistically significant relationship between gender and the different variables of individual and institutional difficulties (with a p = 0.05).

According to Chong et al. (2011), demographic and professional characteristics may play an important part in the results obtained. We can imagine that older nurses with more years of experience in service and profession encounter more constraints to participate in continuing education sessions than younger people.

However, in the present research, the most frequent age range is between 41 and 50 years (28.7%) with a slight predominance of the female gender (56.5%) reinforced by seniority; performing their duties for 10 years (45.4%) and providing services as nursing staff for more than 10 years (50.6%).

This aspect could be due, according to Guiffrane et al., to the experiences acquired by the nurses in previous training courses, such as the training topics proposed were not adequate with their needs, the materials and methodologies adopted were not attractive due to which the transfer of skills after the training sessions was poor. In short, they describe their experience with continuing education as a real failure. In other words, this finding may be an obstacle to participation in future continuing education activities [6].

In the same perspective, the study advocates that the first individual difficulty hindering nurses' participation in continuing education sessions is work overload, which was reported by 85.4%, of which 79.8% are female and 92.6% are male.

This postulate corroborates with the results of Guiffrane et al. (2018), who stated that the highest rate of absenteeism from continuing education sessions (51%) was recorded among the male gender, and mainly those who fixedly work at night. This finding can be explained by the lack of time due to having another occupation during the day (gainful activity, studies) [6]. Also, work overload and family responsibilities of nurses were mentioned as a restriction of nurses' participation in CE sessions by Chong et al., (2011), and Milhomme & Gagnon (2010) [10-15].

In the same framework of ideas, the study also showed that the main organizational difficulties most mentioned by the interviewees were (a) non-targeted content (does not meet the needs of nurses that is 66.7%), (b) lack of follow-up and evaluation of continuing education sessions, that is, 65.3%, and (c) the recommended schedule to CE is not encouraging and not suitable, that is, 54.9%.

This aspect had been identified in the results obtained in the researches carried out Gopee, (2005); Penz et al., (2007); Santos (2012); and Guiffrane (2018) who identified the lack of time and inflexible work schedules as obstacles to participation in continuing education activities [6, 9, 24, 29]. However, in our study, almost all the interviewees referred these difficulties to line managers, who do not take into consideration the importance of accompanying nurses to better target their needs in terms of the skills to be developed to the position they hold.

In our results, we noted three main difficulties in the institutional dimension that hindered the participation of the nurses in the CE sessions; the absence of support measures expressed in terms of follow-up and evaluation to maintain the knowledge and skills acquired during CE sessions in real situations at the work station (88%), the absence of clinical supervision by managers to ensure the application of directives received during assisted CE sessions (86.9%), and the requirement of a schedule to attend CE sessions (57.1%).

This finding is consistent with the results obtained by Santos, who identified the culture of the organization as manifested by a lack of support from managers and colleagues, inability to apply new knowledge in practice, and the risk of being judged by colleagues as one of the barriers to learning by nurses in the workplace or related to their practice [23].

However, this finding contradicts the results obtained by Gopee (2005) and Lee (2011), who emphasized colleague support, motivation, and leadership as individual elements that facilitate the transfer of learning into practice [9-30].

Indeed, for nurses who were frequently evaluated after continuing education, this evaluation reinforced learning and consequently promoted quality education (Eslamian, Moeini Soleimani, 2005). In other words, staff practice should be supervised after any continuing education to ensure that the educational objectives have been met or not [11].

To sum up, the results of the study reveal the existence of factors limiting the participation of nurses in continuing education activities; hence the need of developing a more structured continuing professional education program according to the learning needs of nurses to ensure a participatory approach by nurses in the continuing education. Also, it is time for educators to make the learning experience in continuing education more appealing and attractive by adopting different and more innovative teaching strategies that respond to the different learning styles of nurses.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study in its quantitative aspect have addressed the different factors hindering the participation of hospital nurses in continuing education activities; in addition, the qualitative research has shed light on the obstacles that need to be addressed in order to carry out CE activities by meeting the expressed and declared needs of health professionals. The major challenge for the Ministry of Health decision-makers is to address these multiple difficulties faced by nurses in participating in continuing education sessions.

In this respect, the recommendations proposed in this study will constitute avenues for the improvement and innovation that can promote the participation of nurses in continuing education and consequently the transfer of the knowledge they have acquired to the workplace. Indeed, future research has several interesting avenues for evaluating the effects of continuing education on the quality of care.

LIMITATION

A limitation of our work is that we did not address explanations for the reasons expressed and perceptions developed by the nurses in this study.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Ben M’sik Faculty of Sciences at Hassan II University in Casablanca, Morocco.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals/humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The study was presented and explained to all affected participants, and informed consent was obtained from those who were willing to participate. They were reassured that their answers and their identity would be kept confidential.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data sets used during the current study can be provided from the corresponding author [A.L], upon reasonable request.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the nursing staff and those in charge of continuing education in the various hospitals who participated in the realization of this experiment.