All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Outsiders in Nursing - Voices of Black African Born Nurses & Students in the US: An Integrative Review

Abstract

Purpose:

The purpose of this integrative review was to describe the experience of being outsiders in nursing as described by Black African Born Nurses and Student Nurses (BABN&SN) in the U.S., give voice to their experiences in U.S. academia and healthcare settings, discuss the implications of the BABN&SN othering on the U.S. healthcare systems, and offer recommendations to address the issues based on the literature.

Methods:

An integrative review approach discussed by Whittemore and Knafl was utilized to review literature from nursing journal published from 2008 to 2019.

Results:

Major findings include collegial/peer isolation and loneliness; racism and discrimination, unwelcoming environment, silencing of voices, personal resilience, and sense of belonging. The results of this review indicate that BABN&SN experience in U.S. nursing contribute to harrowing periods of feeling like ‘an outsider.’

Conclusions:

BABN&SN are integral part of the U.S. nursing workforce and the healthcare system. Academic and work environments that support all nurses and students, despite their perceived differences, are essential to promoting an inclusive environment. Understanding the relational pattern that guides the BABN&SN socialization into nursing is vital to developing targeted support especially when entering the clinical practice environment.

1. INTRODUCTION

Globalization has increased the number of Black African Born Nurses and Student Nurses (BABN&SN) in the United States. Internationally Educated Nurses (IENs) from Black African nations migrate in large numbers to the western countries such as the United States (U.S.), the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, and Canada for many reasons. These motives include financial, professional, political, social and personal reasons [1-5]. There were an estimated 1.09 million international students in the U.S. during the 2017/2018 academic year making up 5.5% of all students in U.S. higher education system. Of these, 39,479 (3.6%) were from Africa [6]. Healthcare professions and nursing is a top choice for Black African migrants in the United States because it provides lasting job opportunity lacking in other sectors, as well as existing social networks [7, 8].

Leading U.S. authorities in nursing call for increased diversity of nurses from all backgrounds and cultures as a mean to improve healthcare equity. The National League for Nursing’s statement on Achieving Diversity and Meaningful Inclusion in Nursing Education stated: “The current lack of diversity in the nurse workforce, student population, and faculty impedes the ability of nursing to achieve excellent care for all” [9]. In addition, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) in their 2017 position statement on Diversity, Inclusion, & Equity in Academic Nursing stated: “Inclusion represents environmental and organizational cultures in which faculty, students, staff, and administrators with diverse characteristics thrive” (p.1). Therefore, the need to increase diversity in the nursing workforce to reduce health inequity, improve health outcomes, and address the varied healthcare needs of an increasingly diverse population, cannot be overstated.

According to the Pew Research Center, there were 4.6 million Black immigrants in the US in 2016. Of these numbers, 2.1 million were from African nations which is a 100% increase from 2000. They accounted for 4.8% of the U.S. immigrant population in 2015, up from 0.8% in 1970. Nigeria, Ethiopia, Egypt, Ghana, and Kenya were the top five origin countries of Black African immigrants in the U.S [10]. Black immigrants from Africa are more likely to have a college degree or higher than Americans overall. For instance, 59% of immigrants from Nigeria have a bachelor’s or higher, a number that is nearly twice that of the overall U.S. population [10].

Although a common perception is that immigrant women are poor, uneducated, and unskilled, most African women immigrant who has chosen the nursing profession are highly educated and generally held jobs in their home countries prior to migrating to the U.S [4, 8]. Due to the myriad of prospects offered by the nursing profession and the opportunity to earn good wages and be part of the exciting social networks, many African migrants choose nursing [7, 8].

The growing numbers of Black African migrants contribute to the diversification of the U.S. population which needs diverse health care providers to meet a myriad of healthcare needs. During the adjustment periods in the U.S., Black African nurses and nursing students experience feelings of alienation and isolation. Often colleagues and faculty’s discriminatory, prejudicial practices heighten these feelings in work and academic settings [4, 7, 11-14].

Many Americans view Africa and Africans as “economically and culturally backward, poverty-stricken, disease-ridden, ignorant and other social ills” [8]. Black African born nurses and students expressed the belief that many of their peers, managers, and faculty viewed them through these negative associations and stereotypes. This perception lead to stigmatization across the workplace and educational settings, thereby negatively influencing their interactions with patients, co-workers, supervisors and others they encountered at work [4, 5, 7, 8, 15].

2. BACKGROUND

Inclusion is involvement and empowerment, where the inherent worth and dignity of all people is recognized and barriers to full participation are dismantled. The quality of inclusion must incorporate the nurses’ individual experiences in work and educational settings. According to the report by World Health Organization’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH), “being included in the society in which one lives is vital to the material, psychosocial, and political empowerment that underpins social well-being and equitable health” [16]. The report asserts that inclusion, agency, and control are each important for social development, health, and well-being. As such, restricting participation of all people results in deprivation of human capabilities, which sets the context for inequities [16]. Exclusionary practices create outsiders, cause deprivations, restrict opportunities, prevent full engagement, and widen inequities.

“Social inclusion involves recognizing, respecting and valuing each person, unique identities and group differences, while social exclusion involves rejecting those who differ from dominant social norms… the denial of mutual recognition and human dignity… Misrecognition, disrespect, stigma and fear of difference are forms of social injustice that sustain exclusion. Relational processes of inclusion promote a sense of belonging and acceptance. Having a sense of belonging means feeling comfortable, welcomed and valued [17].

“To be an outsider is to be excluded, to feel low level of belonging, to feel invisible. Being an outsider can make one feel alone, lonely, isolated...faceless, nameless, and voiceless.” “Being an outsider means to be in a permanent state of transition” [18]. An outsider is one “who cannot be trusted to live by the rules agreed upon by the group” [19]. An outsider is one to whom less than normal status has been ascribed by a group of peers and is therefore treated differently because of his/her unfavorable status in the learning or work setting [20]. The degree to which the ‘outsider’s’ personal identity is affected is not known. However, the finding from the reviewed articles revealed group exclusions and personal slights which defined the BABN&SN’s everyday experiences.

To judge the nurses’ experiences in the academic and work environment, we looked at their descriptions of feelings of belonging, isolation, and being included or excluded. We also looked at their descriptions of the attitudes of their colleagues, managers, and instructors, and their perception of availability and adequacy of support systems ranging from professional development and collaboration to provision of reasonable accommodation. Overall, we looked at how this may have influenced their learning, work performance, and sense of identity as well as their physical and psychological well-being.

Several studies have examined the experiences of ethnic minority IENs in the US [4, 21], the UK [5, 22, 23], Australia [24-26], and Canada [27-29]. These authors argued that belongingness is an important feature of nurses’ and students’ experiences within the organizations and it can adversely affect their well-being and transition to practice. All nurses as well as nursing students need to feel welcomed in the clinical setting and feel that they belong before effective learning and integration can take place.

Showers [8] and Iheduru-Anderson and Wahi [4] found that Black African nurses in the U.S. often occupy the lowest level of the racial hierarchy in the workplace. Due to their immigrant status and their accents, peers, patients, and patient’s families viewed them as less intelligent and questioned their skills and competence [4]. Other minority nurses and students sometimes alienated BABN&SN [5, 8, 30].

| - | - | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion 1: | Year of publication | From 2008 to 2019 | Published before 2008 |

| Criterion 2: | Language | Literature in published in or translated in English language. | Published in any language other than English language. |

| Criterion 3: | Terms, concepts, keywords | Black nurses, Black African nurses, Black students, Black African students, African born nurses, African born student nurses, immigrant nurses, internationally educated nurses, foreign educated nurses, International nursing students, | |

| Criterion 4: | Context and field of practice | Nursing education, Practice or professional context. Study conducted in or addressed the United States context | Non nursing studies, conducted outside the US or not addressing US context |

| Criterion 5: | Publication | Peer reviewed and published in a nursing journal. Published empirical studies in valid peer‐reviewed nursing journals CINAHL PubMed, EBSCOhost, PsycINFO, OVID, and Google Scholar. | Non-peer reviewed reports. |

| Criterion 6: | Methodology | Original research study (quantitative, qualitative or mixed method studies) | Non-original research reports, Integrative or literature review research reports, opinion pieces. |

| Criterion 7: | Population | Subjects or participants must be exclusively or include Black African nurses or nursing students. Be nurse or students focused. | Reports did not separate findings about Black African Born Nurses and student nurses. Studies not focused on nurses (including patients, families, broad health service professions, and otherwise unidentified care workers), integration and transition policies not focused on nurses and/or student experiences. |

Feeling alienated and like an outsider leads to emotional and psychological distress, detachment, disengagement (Allan et al., 2009; Levett-Jones et al., 2007), and failure to fully integrate [22] into the work and academic setting. Studies examining the experiences of African Americans in nursing in the US often do not differentiate the experiences of BABN&SN from other Black nurses/students. This present assessment provides the first integrative review of studies on reported alienation and othering of Black African born nurses and nursing students in the US.

2.1. Purpose

This review summarizes the results of articles published in peer-reviewed nursing journals from 2008 to 2019 dealing with Black African born nurses and nursing students. The purpose of this integrative review is to:

- describe the experience of being outsiders in nursing and nursing education as described in literature by Black African born nurses and nursing students in the United States.

- give voice to the experiences of BABN&SNs and highlight the need for open dialogue in schools of nursing and healthcare settings to address racial bias.

- discuss the implications of othering of BABN&SN in the nursing profession in US.

- offer recommendations from literature based on the statements from BABN&SNs.

3. METHODS

The integrative review approach discussed by Whittemore and Knafl [31] was utilized to conduct this review. A manual and electronic database literature search was conducted on peer-reviewed nursing journal articles published from 2008 to 2019 that met the inclusion criteria listed below. The authors independently reviewed full articles based on the prior established inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

3.1. Search Strategy

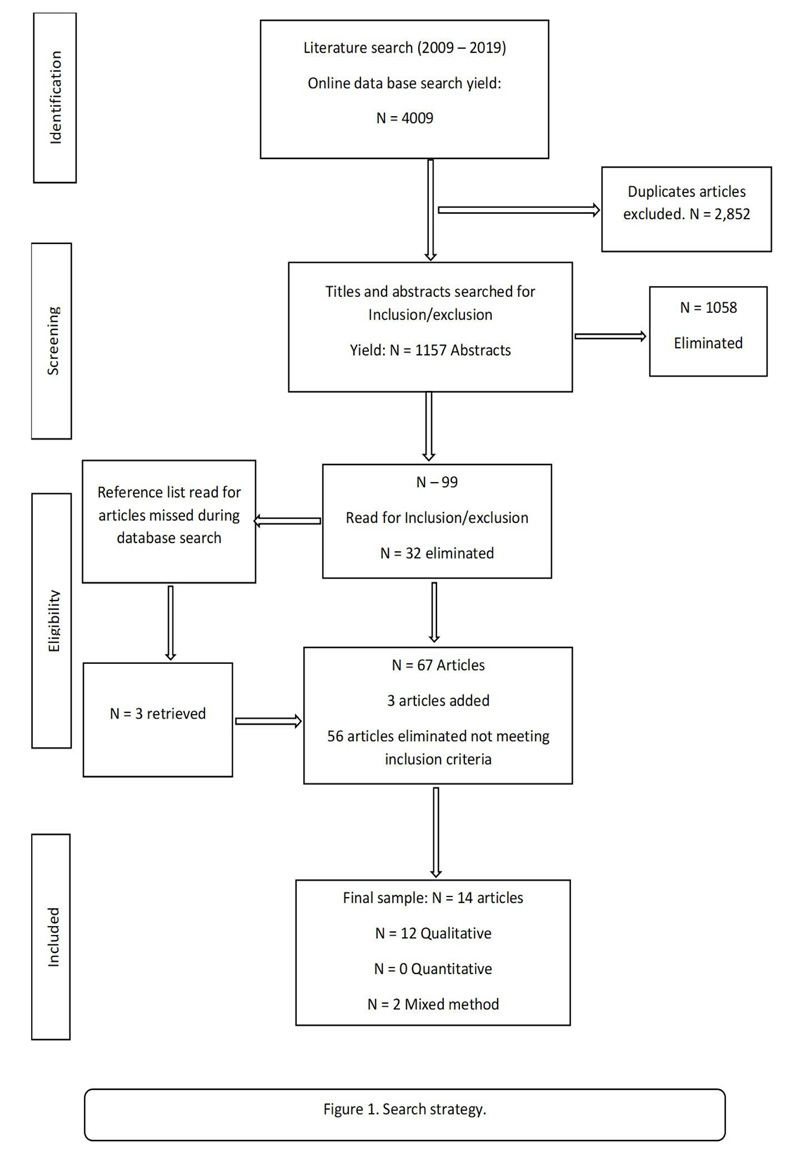

The search strategy (Fig. 1) and the search were designed and performed with the assistance and guidance of the College of Health Professions Librarian. Using a combination of the search terms listed above and the filters as guided by the Librarian, the following databases and electronic journal collections were searched using a detailed and broad search strategy from 2008 to 2019: CINAHL, OVID, EBSCOhost, PubMed Central, and Google Scholar. Reference lists of articles selected for full text review were manually searched. Table 2 is an example of search terms and filters used for the CINAHL database.

| - | Filters |

|---|---|

| foreign educated nurses OR internationally educated nurses OR immigrant nurses

|

2008 to 2019 all results = 862 articles |

| Academic Journals = 694 articles | |

| Abstract available = 571 articles | |

| English Language = 529 articles | |

| United States = 247 articles |

3.2. Methodology

This integrative review follows the five stages of review as proposed by Whittemore and Knafl [31]. These stages include problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation. There has been much published in nursing journals offering expert opinion and suggestions to the experiences of African Americans in nursing in the U.S. However, studies do not often differentiate the experiences of African born nurses and students from that of other Black nurses. Evidence showed that due to the racial and national hierarchies in the nursing profession, Black African Born Nurses (BABN) are at the bottom of the nursing profession’s hierarchy [8, 32-34]. This present review provides the first integrative review of studies on reported alienation and othering of Black African born Nurses and Nursing students in the United States.

4. RESULTS

Of the 14 articles included in this review, ten utilized a qualitative methodology employing open-ended interview, focus groups, or questionnaires that included open-ended items to explore and analyze the views/experiences of BABN&SN in the different levels of nursing education. The reviewed studies are summarized in Table 3. It was generally noted across the literature that BABN&SN have negative experiences in nursing in the United States, especially in predominately White schools of nursing and organizations. The findings from the reviewed studies are organized into the following themes: collegial/peer isolation and loneliness; racism and discrimination, unwelcoming environments, stereotyping, and silencing of voices. Financial constraints contributed to the experiences of these nurses and students; however, personal resilience, sense of belonging, and being included were very strong determining factors in their persistence, academic success and career growth. In presenting the themes some direct quotes from the reviewed studies has been included. Recommendations from the reviewed literature is provided.

Table 3.

| Author/Year | Location | Purpose of the Study | Methodology / Design | Participants / Sample Size | Findings | Selected Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ackerman-Barger, K., & Hummel, F. (2015) | USA | To illuminate the education experiences of nurses of color. | Used critical race theory (CRT) and CRTE framework Narratives were gathered through individual interviews. | 7 nurses of color | Experiences of Exclusion; Survived Social Prejudice; Required to Defend Self; identified as Different; Confronted by Racism; Proceeded with Caution; Made to feel guilty; Made to feel like the Outsider; Discouraged from pursuing a Nursing Career; Referred to Academic Resources; Validated for Who One Is; Encouraged to Succeed; | Knowledge about and appreciation for the education experiences of students of color are essential to create inclusive teaching and learning environments. |

| Allen, L. A. (2018). | USA | To explore the experiences of internationally educated nurses in management positions in United States health care organizations. | qualitative, phenomenological study, | 7 internationally educated nurses | Supervisors contributed to the participants’ acceptance of management positions. The participants experienced challenges such as job | Organizational leaders need to address diversity and cultural marginalization, which were challenges foreign educated nurses. Require all employees to complete cultural and diversity training designed to increase cultural competence and increase inclusiveness. Facilitate professional development opportunities. |

| - | - | - | - | - | responsibilities, cultural differences, language and communication, Work relationships and support, opportunities for education and professional growth. | - |

| Ezeonwu, M. (2019). | USA | Documents the perspectives of African-born nurses on their baccalaureate nursing education experiences in the United States. | descriptive study used qualitative | 25 African-born nurses | Themes were disused under four major headings. RN-to-BSN Education Challenges: Individual; Institutional Challenges: RN-to-BSN Success Factors: Individual: RN-to-BSN Success Factors: Institutional; Practical Program Design. RN-to-BSN Success Factors: Institutional Practical Program Design. Helpful Campus Resources. | Nursing program administrators must promote welcoming learning environments that challenge faculty and staff to not judge ethnic minority students’ abilities based on their language skills. Encourage Nursing faculty and staff actively participate in at least quarterly implicit bias workshops. |

| Iheduru-Anderson, K. C., & Wahi, M. M. (2018). | USA | To characterize the facilitators and barriers to transition of Nigerian international educated nurses to the United States health care setting. | Descriptive phenomenology approach, | 6 Nigerian nurses | The three major themes identified from the participants’ stories were “fear/anger and disappointment” (FAD), “road/journey to success/ overcoming challenges” (RJO), and “moving forward” (MF). | Examine organizational facilitators and barriers to IEN adaptation to US healthcare settings. Increasing facilitators, such as improving job orientation and ongoing mentoring, and decreasing barriers, such as taking actions to reduce racism and inequity, which would likely result in improved outcome with a more efficient adaptation of IENs to their new environment. |

| Jose MM. (2011). | USA | To understand the lived experiences of IENs in the USA to create evidence-based interventions for fostering their adaptation to living and working in the USA. | Phenomenological study | 20 internationally educated nurses: 8 from the Philippines, 7 from India and 5 from Nigeria | The themes follow a trajectory of experiences, which the study group described as: (1) dreams of a better life, (2) a difficult journey, (3) a shocking reality, (4) rising above the challenges, (5) feeling and doing better, and (6) ready to help others. | Employer should identify the learning needs and provide appropriate orientation content suitable to the needs of the new IEN. Employer should invite IENs input when developing programs aimed at facilitating adaptation and support IEN to improve success and retention in the US workplace. |

| Junious, D.L., Malecha, A., Tart, K., & Young, A. (2010). | USA | To describe the essence of stress and perceived faculty support as identified by foreign-born students enrolled in a generic baccalaureate degree nursing program. | Mixed method study using an interpretive phenomenological and supplementary quantitative triangulation. | 10 students enrolled in a generic baccalaureate degree nursing program. Including students from Nigeria. | Desire to be valued and accepted by the nursing faculty, their classmates, and the educational institution leading to patterns of stress, strain, financial issues, having no life, and lack of accommodation as an international student. Cultural ignorance: Language issues, stereotyping and discrimination, cultural incompetence. | There a great need for updated research on nursing student stress but how faculty can affect stress experiences of student nurses. |

| Love, K. L. (2010). | USA | To explore the lived experience of African American baccalaureate level students with socialization in one nursing school. | Colaizzi’s (1978) method of descriptive phenomenology | 7 participants: 2 from Jamaica, 1 from Haiti, 3 students of African descent born in the United States, 1 African American | The following six themes emerged: | Nursing education should include a less Eurocentric curriculum. Nursing need to examine the effects of dissonant socialization experiences on students, nursing practice and care outcomes in a highly global society. |

| - | - | - | - | - | 1—The Strength to Pursue More, | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | 2—Encounters with Discrimination, 3—Pressure to Succeed, | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | 4—Isolation and Sticking Together, | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | 5—To Fit in and Talk White, and | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | 6—To Learn with New Friends and Old Ones. | - |

| Mulready-Shick, N. (2013). | USA | To explore the experiences of students who identified as English language learners (ESL). | Interpretative phenomenology and critical methodologies | 14 nursing students who identified as ESL. From Central America, South America, and Africa. | Academic progress involved additional time and effort dedicated to learning English and the languages of health care and nursing. Traditional and monocultural pedagogical practices, representing acts of power and dominance, thwarted learning. | More inclusive teaching practices such as slowing down while speaking as a powerful step towards creating equitable communication. Reducing linguistic and cultural biases in faculty-made exams. |

| Sanner, S., & Wilson, A. (2008). | USA | To describe how ESL students described their experiences in a nursing program. | Qualitative study | 6 ESL (1 from Liberia) | Three themes walking the straight and narrow, an outsider looking in, and doing whatever it takes to be successful. Participants shared instances where ESL may have contributed to academic difficulty but did not perceive that ESL was the primary reason for course failure but attributed it to experiences of discrimination and stereotyping. | Faculty must exercise caution when interacting with ESL students to avoid stereotyping and disregarding students’ individual circumstances. |

| Scherer, M. L., Herrick, L. M., & Stamler, L. L. (2019). | USA | To understand the learning experiences of immigrant registered nurses who graduated from an entry-level baccalaureate nursing program in the United States. | Hermeneutic phenomenology integrating Heidegger's (1927/1962) | 5 foreign born nursing students. 3 Black African Born | Analysis identified an overarching theme, “being on the outside” alone in their learning and ignored by their peers, faculty, and nurse preceptors. 4 subthemes include; Harsh realities, Nurturance, Disruptions, Propagation | Nursing scholars, educators, and nursing preceptors need to examine assumptions and conceptualizations. Nurse educators should maintain an all-inclusive learning environment where differences are respected and appreciated. |

| - | - | - | and Gadamer's (1960/2004) methodologies | - | - | - |

| Smith, A., & Smyer, T. (2015). | 2015 | To gain an understanding of how Black African nurses experience nursing education within the United States. | A hermeneutic phenomenological | 9 Black African immigrants | Essence: Optimistic Determination; Academics: Language, testing, technology; Culture: cultural competency, motivation, view of nursing, view of education; Competing demand: work, family; Relationship: Language, faculty, classmates, clinical. | Provide a supportive and inclusive classroom environment. It is |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | recommended that nursing faculty reach out and take an interest |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | in the Black African student to form strong, supportive, |

| - | - | - | - | - | - | and caring relationships. |

| Vardaman, S. A., & Mastel-Smith, B. (2016). | USA | To describe the transition experiences of international nursing students using transitions theory as the basis for the investigation. | A descriptive phenomenological design. | 10 students. Including St. Lucia (n =1), Rwanda (n = 1), and Nigeria (n = 1). | Meaning of Studying Nursing in the US; Expectations of Coming to the US to Study Nursing; Knowledge of US and Nursing School Prior to Coming | Create mentoring programs for new international students. Matching new students with successful international students who are progressing through the curriculum might foster increased social support. |

| - | - | - | - | - | to US; Planning Prior to Coming to US and College; Perception and Interaction with the Environment; Emotional Well-Being; Well-Being of Interpersonal Relationships; General Sense of Well-Being. | - |

| Wheeler, R. M., Foster, J. W., & Hepburn, K. W. (2014). | USA | To gain a deeper understanding about the experiences of IENs compared to those of US registered nurses (RNs) practicing in two urban hospitals in southeastern USA. | Cross-sectional, qualitative, descriptive design | 82 female registered nurses. 42 IENs and 40 US (13 from Sub-Saharan Africa and 7 from the Caribbean) | IENs reported feeling isolated in two ways: cultural and professional isolation. describe disconnection from both patient and workplace when discrimination is overt and pervasive. Decision to leave non-supportive workplace. | Training in conflict resolution as well as cultural sensitivity could be part of the requirements for all nurses, especially nurses in supervisory positions. |

| Whitfield-Harris, L., Lockhart, J. S., Zoucha, R., & Alexander, R. (2017). | USA | This study explored the experiences of Black nurse faculty employed in predominantly White schools of nursing. | Hermeneutic phenomenology | 15 Black nurse faculty. | Four themes were extracted from the data: (a) cultural norms of the workplace, (b) coping with improper assets, (c) life as a “Lone Ranger,” and (d) surviving the PWSON workplace environment. | Assess cultural competence in PWSON; develop trainings and curricula that focus on cultural competence; develop strategies to improve the workplace environment, professional socialization, and emotional and moral support for faculty to improve recruitment and retention of faculty. |

| Summary of reviewed articles identifies author(s), region, study purpose, sample, brief description of findings, and select recommendations for each study. | - | - | - | - | - | - |

4.1. Collegial/ Peer Isolation and Loneliness

All the reviewed studies indicate that social isolation and loneliness are important obstacles experienced by the BABN&SN in the academic and clinical settings. The low numbers of Black minority faculty and students in nursing programs limits the opportunities for students to connect and develop relationships with faculty and other nursing students leading to the feelings of social isolation and loneliness [4, 7, 14, 35-44]. Contributing to the sense of isolation are language and accents [45]. Love [39] conducted a descriptive phenomenology study to explore the lived experiences of African American baccalaureate-level students with socialization in one nursing school. A major theme that emerged from this study was isolation and sticking together. Participants in this study reported that they “felt isolated from their classmates and singled out.” One stated “I noticed I was put on the side” [39]. There was also self-imposed isolation by the BABN&SN in attempts to distance themselves from their peers to avoid embarrassment related to course grades and accents. The participants reported that the painful experiences of discrimination and isolation came from many sources, including teachers, students, nurses, and nurses’ aides. One of Love’s participants described her appalling experience of discrimination and isolation as follows: “Being with White people feels like you are sitting on pins and needles. Like you are sitting on something that’s going to hurt you any minute” [39]. Such feelings as described above limited interactions with the majority peers and heightened the feeling of being othered for these students.

Compared to White nursing students, Black nursing students experience higher attrition from nursing programs [35]. This high attrition has been attributed to poor sense of belonging, lack of connection, and poor academic performance [7, 37, 39, 40, 45]. Evidence from literature indicates that the attrition of Black students related to isolation can be mitigated by both academic and interpersonal support [7, 35, 38, 39]. Social connections and friendships beyond the classroom and the work environment are important in building a sense of belonging that fosters peer support, a sense of community, and improved academic and work performance.

Collegial/peer isolation hinders these BABN&SNs from being assertive and successful [4, 14, 35]. Studies affirmed that the African-born Nursing students’ experiences of isolation and non-inclusive institutional climates have significant effects on their academic performances and outcomes [7, 14, 40, 41, 45]. In the Love [39] study, almost all the participants indicated that they experienced a lack of confidence, diminished self-esteem among the white students, fear and isolation from their classmates, and the pervasive sense of being alone. This finding was consistent with that by Ackerman-Barger & Hummel [35] that reported the need for inclusion and equity in nursing education and, ultimately, in healthcare. Ackerman-Barger & Hummel (2015) used a narrative inquiry to capture the educational experiences of nursing students of color. The participants shared their stories of racism, prejudice and isolation in the theme of exclusion and reported that these issues were prevalent with both their peers and nurse educators. One participant shared the experience of peer racism and isolation stating:

“Serena: ‘Sometimes you don’t have any support and you have to do everything on your own. Like even in the classroom I feel like I can’t ask a question, I have to do it later. I have to wait to talk to the professor. It is really very lonely. And you have to be really careful. I don’t know. I don’t know how to explain it’” [35].

Although the increased need for diversity in nursing is not new and many positive impacts of cultural diversity have been reported, concrete plans to successfully address the issues that contribute to collegial isolation in nursing is lacking. Mulready-Shick [45] stated that some of the setback factors may include faculty bias and perspectives towards the minority nursing students. Black students in Love [39] reported being the last to be chosen as partners in class/clinical group work and being unable to find classmates willing to form study groups with them. Junious et al. [38] reported that many black students shared an extremely strong desire for support, understanding, and overall acceptance from nursing school classmates and faculty.

Consensus on how to eliminate this pervasive issue has been negatively affected by multiple factors including but not limited to poor implementation of organizational/institutional policies, cultural incompetence of faculty and staff [7, 35], and inability or unwillingness of nurse leaders and faculty to confront and address the issue head-on. Indisputably, professional socialization in nursing programs is more congruent to white majority students than those of racial and ethnic minorities [7, 14, 35, 37, 39]. A participant in Ackerman-Barger & Hummel [35] study described the experience of isolation from nurse faculty as “an eye-opener to me on the power of racial mind-raping in the classroom” (p. 41-42).

4.2. Racism and Discrimination

The discrimination experienced by the BABN extends beyond racial differences and relates also to their accents and perceived cultural differences from their country of origin [7, 38]. The perception that nursing faculty members have negative biases and attitudes toward minority students was expressed in many of the studies [7, 35, 39]. Ezeonwu [7] analyzed the views of African-born nurses on their RN-to-BSN education experiences in the United States. Results showed that socio-cultural adjustment associated with language barriers, discrimination and psychological intimidation was a top challenge identified by the participants. Describing her experience of discrimination, one student said: “I felt like an outsider in the school. It was hard to know anybody in the school when you are a minority” [7]. Issues related to language, heavy accents, and overall communication emerged as significant stressors and a key source of discrimination [4, 7, 38, 43]. The minority students of African descent were often looked down on. They lacked confidence in their own capabilities because of their inability to speak and sound American [4, 7, 36, 37, 39, 41, 42]. International students have different learning needs, more obstacles to overcome, and require additional coping strategies compared to their non-international classmates (Vardaman & Mastel-Smith, 2016), which may increase the feelings of otherness that they experienced.

The reviewed studies concur that increased diversity in nursing will improve the problems of racial discrimination and intimidation experienced by the black/minority nurses in both academia and the workforce. The distressing impacts of discrimination and racism expose these individuals to both physical and psychological ill-health (Ezeonwu, 2019). Ezeonwu’s (2019) findings indicated that working with faculty and advisers that are good listeners, patient, and approachable had great positive impact on Black African students’ success. The reviewed studies agreed that discriminatory/racial based barriers hinder internationally born nurses’ ability to working at their highest professional skill and advancement. As a result, BABN&SN may be forced to remain fearful outsiders, and may not be able to succeed in nursing education or aspire to their fullest potential in the nursing profession [4, 36, 38, 41].

The negative effects of language and accents among minority students, including its association with the concepts of language bias and racism, are replete in the literature [14]. Often accent bias led to low grades and misinterpretation of the students’ ability to interact with peers and patients. The most common reason given by educators for failing students was that the student was a poor communicator [14]. Communication encompassed both verbal and written interactions with patients, faculty, and staff nurses. DeBrew et al.’s [46] study of nursing faculty decisions to fail or pass students in clinical courses indicated that foreign students with English as a second language were likely to fail clinical courses due to faculty’s perceptions of the students’ ability to communicate. For example, a participant in their study reported: “ I had a student that was really afraid of patients. She just didn't know how to communicate with them” [46].

Mulready-Shick [45] argued that since the students’ communication provides incomplete evidence of their thought process, the inclusion of other multi-contextual instructional strategies should be considered. The findings from Smith and Smyer [14] indicated that the nursing faculty struggled in grading the BASNs in classroom and clinical settings due to their accents and as such viewed them as outsiders in nursing education. The fear of being mocked or saying words incorrectly detracts from the chances of successful program completion, especially when working with language biased faculty [7, 38, 45]. Similarly, test questions may be answered or graded incorrectly by the faculty because of language confusion [14, 41]. The BABN&NS endure discriminatory and prejudicial treatments that predisposed them to stress related to acculturation, thus negatively affecting their assessment and evaluation [14, 36, 39, 42, 44]. Students whose cultural norms do not allow public assertiveness are viewed as inefficient nursing students and that can affect their level of success in nursing programs [42]. The participants of the Smith & Smyer (2015) study reported that the culture was noted as the basis of fear of participation in both clinical and classroom settings as described by one participant:

“Being raised in a society where you are told you have to be polite, you cannot be talking in front of your elders, so we are not graded on participation, so you have to force yourself to answer questions. You are competing with what you are taught not to do” [14].

The experience of discrimination was further highlighted by the following statement from another participant in Smith and Smyer (2015) phenomenological study of Black African nurses experience in nursing education in the US:

“When the instructor said you need to participate in group studies, there is differentiation, people tend to segregate based on their racial perception of self…You find the African students tend to go to African students. Americans tend to go to Americans, whites tend to go to whites, Indians tend to go to Indians, so it is more of a segregation of some sort, and if you didn’t have anybody from your culture, from Africa, then you are stuck and you are having to go through trying to fit in” [14].

Smith and Smyer [14] affirmed the importance of understanding Black African culture as a facilitator for success of BASN, particularly related to their own cultural competence in navigating the new western culture and the new educational environment.

Similarly, Allen’s [36] study found that the Black nurses transitioning into the managerial roles are also faced with the challenges related to discrimination and language. Allen [36] explored the experiences of internationally educated nurses (IENs) in management positions in United States health care organizations. The problem of discrimination related to language /accent was a significant finding. The participants described various difficulties related to their accents and communication methods. The author reported that the participants were seen and treated as “outsiders” in hospitals with homogenous Caucasian nurses and as such they struggled to find their place in the organization’s culture. The author stated that the internationally educated nurses’ feelings of exclusion may indicate that their supervisors had low levels of multicultural understanding or recognition of cultural differences and their values. Studies have reported that the leadership strategies that are effective for US-educated nurses are not always appropriate for internationally educated nurses [36, 43].

4.3. Unwelcoming Environments

Several studies exploring the experiences of minority students and nurses have contributed to the knowledge of BABN&SNs’ adjustment to their new environments [4, 7, 14, 35, 38-42]. These studies consistently found that international students and nurses experience new cultural practices and detachment from home, a place where they felt comfortable and secure. Although results showed that some minority nurses and students easily adapted to their new environments, a majority were faced with several adjustment challenges when transitioning into their new environments [4, 38]. Acclimatization into the new culture was noted to be very challenging to the participants in Junious et al. [38] study, which worsened the silencing of voices. One participant described the situation as:

“In my culture, when you talk to someone...that has authority above you, like an [older adult], we try to show respect I will just look down. I’m listening, but I don’t have to necessarily look into [his or her] eyes, but when my teacher does this literally do this (participant demonstrated how the instructor pulled her chin up) looks at me and gets so close, I’m so uncomfortable” [38].

Iheduru-Anderson and Wahi (2018) used a qualitative descriptive phenomenology to examine the transitional experiences of Nigerian internationally educated nurses (NIENs) transitioning to US health care settings. On the most predominate theme of fear/anger and disappointment, the participants reported that the humiliation from both peers and patients created an unwelcoming and hostile work environment. The NIENS were seen and treated as outsiders by both peers and patients (Iheduru-Anderson and Wahi, 2018). One participant reported:

“The nurses I worked with there were horrible. They were insensitive, they acted like they did not want me there. They gang up on me and they were always reporting me to the manager, for no apparent reason Overall, it was a hostile environment” [4].

As reported in similar studies, the participants survived the problem of fear and isolation through resilience, hard work and determination. In congruence with the above findings, Jose (2011) conducted a study using the qualitative psychological phenomenological method to elicit and describe the lived experiences of internationally educated nurses (IENs) who work in a multi-hospital medical center in the urban U.S. The author reported that nearly every participant revealed their experiences of fear, criticism, and discrimination from their peers. These created unwelcoming work environments and hindered their transition to practice in the US.

4.4. Stereotyping and Silencing of Voices

Many decades of research on stereotype threat suggest that concerns about negative stereotypes can undermine performance and create group differences in the educational and organizational outcomes achieved by stigmatized groups. The academic underperformance of racial and ethnic minorities at select colleges and universities is well-documented [38]. Junious et al. (2010) conducted an interpretive phenomenological study to examine stress, experiences, and perceptions of faculty support among foreign-born generic baccalaureate nursing students. The finding showed that all the participants experienced some form of cultural ignorance at some point during their nursing education. The experiences included language issues, stereotyping, discrimination, and cultural incompetence by the dominant culture. The participants reported that they were viewed as “dumb” because of their accented English.

Negative stereotypes of BABN&SN are evident in how BABN&SNs are treated by their peers. As discussed by a participant in Ackerman-Barger and Hummel [35]:

Yeah, sometimes when we have a group project and we come together and people have different suggestions and that was okay, but when I give a suggestion, they looked like they were not hearing what I am saying, or you are a dumb person. It make (sic) me feel like I was dumb or something like that. But when they check it out later, they would say, “Oh that was a good idea!” or “Oh yeah you were right.” But that would be maybe two or three days later. People don’t get to know you. They judge you!” [35].

Stereotyping of Black nursing students created self-doubt, a sense of paranoia, lack of confidence, and diminished self-esteem. Students felt like they did not belong and should not get “too comfy,” but “they are sitting and waiting for you to fail” [39]. Participants in Love (2010) discussed negative stereotypes experienced from faculty and peers. For example, the following excerpt was reported by a participant after a nurse instructor discussed with a white student an interaction she had with a black student stating: “She (the instructor) told a White student who said ‘be careful what you say before you get run over in the street or hear gunshots outside of your house.’ The teacher laughed” (p. 346). As Love appropriately noted, the previous negative stereotypical and prejudicial comment not only implied that the Black nursing student was “violent or involved in a gang… the teacher’s behavior fostered another type of discrimination” (p. 346). The instructor did not make any effort to reprimand the student for the negative racist comment but instead acknowledged and condoned it by laughing [39]. Comments like the one described above created hostile learning environment for the students.

4.5. Financial Constraints

One of the major shared experiences of Black African Student Nurses (BASN) was financial challenges and many reported that it was necessary to have multiple jobs in order to make ends meet [7]. However, several studies have attributed the financial difficulties/stressors of the BASN to cultural obligations of supporting families in their homelands [7, 14, 45]. The result from the Ezeonwu [7] study indicated other identified barriers to include intimidation by faculty and staff, poor awareness of and accessibility to financial aid information regarding scholarships and grants, technology, and problems with communication. The participants asserted that the orientation and exposure to other support networks and resources included but was not limited to friends, peers, provided support, and strength. The lack of knowledge regarding how to access available financial resources may heighten the feelings of otherness experienced by BABN&SN. Working long hours also limited the time available to socialize with peers.

4.6. Personal Resilience

Resilience is defined by Grafton, Gillespie, and Henderson [47] as “innate energy or motivating life force present to varying degrees in every individual, exemplified by the presence of particular traits or characteristics that, through the application of dynamic processes, enable an individual to cope with, recover from, and grow as a result of stress or adversity.” Personal resilience and determination are common findings in the literature that contributed to academic and career success. Although literature is replete with negative experiences related to social isolation, discrimination, unwelcoming environments, and intimidation, personal resilience and determination to succeed seemed to overcome these experiences. Many BABN &SN reported personal and family commitment and responsibility as very strong reasons to remain focused. One nurse in the Iheduru and Wahi [4] study described her resilience with the following: “hard work, determination. I am not a quitter, I still have an accent, but I have learned to speak so they can understand me better” (p. 607). Personal motivation and survival needs strengthened their resilience. Some of the nurses reported not having other choices, meaning that failure was not an option and that they needed to succeed at all costs.

Many of these nurses exhibited the ability to learn from their experiences and adapt in order to build greater resilience in the face of future adversity. As many of the students who fail or drop out of nursing programs were Black students, many of the BASNs feel the pressure and will do whatever it takes to prosper where those students could not. As noted in Love [39], “several students stated that they “pushed even harder” to prove they could be successful” (p. 346). Their belief that the faculty and non-minority students expected them to fail or withdraw from the program motivated them to work harder to be successful. “They felt the expectation of African American students failing, but that belief pushed them to new levels of determination to prove that they were “as smart as anyone else”. One student described, “You feel like there’s a bet going on and if you fail, you’re proving them right” [39]. Studies also showed that family commitment and responsibility converged to drive the personal resilience and determination of BABN&SNs both in academia and in practice. The determination to succeed is common among other ethnic minority populations in nursing [48].

4.7. Sense of Belonging and Being Included

Being included means to belong. Belongingness is the experience of personal valued involvement in a system or environment. According to Maslow, belongingness is a basic human need. Maslow (1987) as cited in Levett-Jones, Lathlean, Maguire, & McMillan [49], described belongingness as “…the human need to be accepted, recognized, valued and appreciated by a group of other people.” Potential consequences of exclusion include anxiety, stress, depression, and a decrease in general well-being [49]. Several of the studies discussed the nurses’ and students’ experiences with eventually gaining a sense of belonging. Being included meant support from others (peers, colleagues, faculty, and nurse leaders), recognition, mentoring, referral for academic support, validation, and encouragement to succeed [35].

The literature revealed that BABN&SN presented a great need to fit in. To establish a strong sense of belongingness and integrate successfully within the institutions, many BABN&SN “transformed their identity” [44]. This loss of personal identity was articulated by Love (2010) and Whitfield-Harris et al. [44]; Black students and nurses who successfully adjusted and conformed to the dominant cultural norms of the institutions had difficulty remaining authentic to their own identity and being accepted while going through the transformation. Changing personal identity and conforming to the dominant cultural norms was viewed as a survival skill. Once full assimilation was achieved, these nurses and students experienced improved relationships with their peers and faculty overall. Communicating with accents was a very strong barrier to attaining a sense of belongingness (Ackerman-Barger & Hummel, 2015; Iheduru-Anderson & Wahi, 2018; Jose, 2011; Love, 2010; Sanner & Wilson, 2008; Vardaman & Mastel-Smith, 2016; Wheeler, Foster, & Hepburn, 2014). Therefore, modifying accents and speaking/sounding more like their American-born counterparts was a tool used to overcome stereotypes.

Notably, the benefits of conforming were increased belongingness and inclusion. For the BABN&SN, that meant increased support from and mentoring by faculty and peers, exposure to academic resources, more friends, invitations to social events, and recognition as a member of the team [4, 7, 14, 35, 39]. Validation was described as being acknowledged as an individual and treated with respect. When faculty and peers took the time to learn about the nurses personally, it increased their sense of belonging. Faculty who made BABN &SN feel included was described as friendly, “engaging, supportive, loving” [35], “approachable, accommodating, accepting, nice,” [42].

Positive relationships between the BABN&SN and their peers contributed to an increased sense of belonging and inclusion. Perception of colleagues included feeling welcomed, being treated as an equal, and being defended when bullying, negative comments, or discriminatory treatments were observed. The nurses reported an increased sense of belonging when they had more positive interactions with their colleagues. For example, a participant in Iheduru-Anderson and Wahi [4] described one of her colleagues as a “lifesaver,” while another participant in Ackerman-Barger & Hummel [35] described a connection she had with a professor of the same race and ethnicity as being “supported by someone who understood her” and making a difference in her success in nursing school. In Love [39], participants talked about forming alliances with other Black students stating: “Even if we don’t know each other,” sticking together provided “safety” and “strength” (p. 346). Participants in Vardaman and Mastel-Smith [42] reported relationships with peers from similar backgrounds that were “like a little family” (p. 40). Informal socialization outside of work and school was a powerful mechanism for increasing the nurses’ sense of belonging. Although many of the nurses reported not being able to join some of their peers for after work or school social activities, they felt a sense camaraderie by being included in non-work-related conversations that improved peer relationships. These informal interactions increased trust, self-esteem, and feelings of being valued as members of the team.

5. DISCUSSION/RECOMMENDATIONS

The inequity, discrimination, and toxic environments that exist in nursing education and practice environments are important issues of local, national and international concern [4, 14, 35, 38-41]. This integrative review found that there is much congruency in perceived barriers experienced by BABN&SN in nursing programs and workforces throughout the US. African migrants work hard to establish their paths through education in order to thrive in the US while maintaining cultural values from their countries of origin [7]. This, however, poses significant problems with being accepted and forming relationships, leading to the status of perpetual otherness. Studies showed that the BABN&SN are exposed to racial hostility, discrimination, rejection, isolation, ridicule, and intimidation [4, 43]. The effects of prejudicial and discriminatory practices impact the success of Black nursing students. Perpetrators include nursing faculty and staff, colleagues/peers, patients, and organizational leaders [43]. Negative interactions with faculty, especially in front of other students or staff, can be humiliating and devastating for any student and especially for BABN&SN who are already experiencing undue stress from navigating sometimes unfamiliar cultural environments.

Several studies provided concrete recommendations for improvement, while others provided more general suggestions that may contribute to improvement in the experiences of BABN&SN (Table 3). Love [39] recommended that nursing programs adopt less Eurocentric curriculum when reviewing textbooks and curricula to support diversity in healthcare. To increase diversity in nursing, the nursing profession needs to bolster the success of all students including BABN&SN in nursing programs. The improvement and transformation of inequity in nursing education must be addressed and made visible in the healthcare system [39].

Creating more inclusive workplaces and teaching environments is emphasized in the reviewed studies, as crucial for all nurses and students. Mulready-Shick [45] recommended encouraging more inclusive teaching practices, slowing down while speaking, and allowing the students more time to articulate their thoughts while expressing themselves as easy steps to promoting more equitable communication. DeBrew et al. [46] emphasized the importance of hiring diverse nursing faculty who will not only reflect the diversity of the patient population but also that of the registered nurse workforce [14]. Allen [36] affirmed that healthcare organizations should adopt training strategies to support individuals from different cultural backgrounds.

Iheduru-Anderson & Wahi [4] and Jose [37] called for internationally educated nurses orientation programs to include language and health care communication skills, education about hospital policies and procedures, updates on health care technology, and cultural differences and challenges related to migration. Peer support, emotional and family support, social interactions through contact with students and faculty, financial support, and advocacy by faculty were factors reported to positively impact BABN&SN success in nursing. Faculty facilitated peer interaction through collaborative group projects may also aid in fostering peer relationships.

5.1. Nursing Practice Implications

Perceptions of discriminatory educational climates and lack of faculty support negatively affected students’ learning and academic performance [7, 50, 51]. There are consequences which could be psychological and physical for nurses who feel excluded in the workplace. Alienation, insecurity and anxiety attributed to psychological consequences may be detrimental to the patients safety [43]. They may not speak up even when safety issues are observed for fear of retribution [4, 12, 14, 37].

The participants’ experiences in these studies diverged from the nursing profession’s philosophy of advocating and caring for others. Nursing leadership must do more with the assessment of workplace culture that perpetuates the othering of its constituents. Creating an environment that champions and supports all individuals, despite their skin color, place of origin, or manner of speaking is essential to promoting the kind of truly diverse and inclusive environment that can address the health and healthcare disparities of the U.S.

Understanding how Black African nurses and students experience nursing practice and education in the U.S. has implications for promoting their recruitment and retention. Nurse leaders and faculty must recognize and value the cultural differences of Black African nurses and student in order to provide a supportive and inclusive work and classroom environment. Debrew [46] challenged short-term fixes such as an occasional cultural competency programs for nurse educators and called for a more robust institutional change to improve nursing education. Most of the studies recommended hiring diverse nursing faculty who reflect the diversity of the patients as well as that of the workforce.

The outsider status of BABN&SN may function to provide their peers with the security of knowing that, whatever the configuration of the nursing professional status hierarchy, they will likely never be found at the bottom because that place is held by BABN&SN. However, reasonable and responsible nurse faculty are in positions to positively shape students’ experiences within the learning environment. Faculty can help BASNs learn to ask questions, improve their communication skills, and talk about their feelings and desires.

5.2. Limitations of the Review

One limitation of this review is the number of resources included. The review only included studies published in peer-reviewed nursing journals from 2008 to 2019, therefore studies published in non-nursing journals would have been missed and some of the experiences with BABN&SN would not have been included. All studies of various designs were included in the review; however, no quality assessment of study design was included. Another limitation is the type of studies used in this review. The majority of the articles cited are qualitative articles. This limitation is consistent with Whittemore and Knafl’s [31] approach; including all evidence means that potentially weak evidence is also included. Small sample sizes limit generalization; however, they provide rich data related to the participants’ experiences as outsiders in nursing practice and education. This review was limited to the literature examining Black African born nurses and students; it will be important to examine other minority subgroup experiences to understand how their experiences compare to that of the current population. Another limitation is that this study provides no clear insight on what strategies that the nurses and students used to find success and navigate their actual and perceived challenges. Increased understanding of the processes that enable these nurses to adapt successfully, and of the limitations on successful coping of those who did not succeed in nursing education, can provide insight into the principles underlying their success and resilience. This understanding can also guide intervention efforts to promote success for students and decrease the feelings of alienation that affect full inclusion and engagement in the workplace. Quantitative study with larger sample sizes is needed to further examine the experiences of these nurses and students in the United States. As previously stated, the consequences of exclusion and poor sense of belongingness such as stress, anxiety, depression, and reduced self-esteem significantly impede learning. There must be a greater understanding of the impact of full inclusion on BABN&SN learning and success in nursing.

CONCLUSION

This review of the most current literature explores the experiences of BABN&SN in the United States. It is evident in the literature that these nurses and students continue to experience alienation in nursing education and practice which stem from biases and discrimination present at both the institutional and individual levels. Creating an environment that supports and encourages all individuals despite their physical and cultural differences is vital to promoting the diverse and inclusive environment required to address healthcare disparity in the U.S. Achieving cultural competence and reducing healthcare disparity without having authentic conversations about racial biases and prejudices in nursing will prove difficult. Understanding the relational pattern that guides the BABN&SN socialization into nursing is crucial to developing targeted support especially when entering the clinical practice environment [52]. Nurse educators must be more aware and use language that is inclusive with students [45, 53]. Nursing leadership needs to do more with the assessment of workplace culture that perpetuates the othering of its constituents. Nursing must create safe spaces for authentic discussion of the underlying racial issues contributing to these ongoing problems.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

FUNDING

None.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.