All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Exploring the Meaning of Coproduction as Described by Patients After Spinal Surgery Interventions

Abstract

Background:

In the procedures of surgical pathways it is important to create opportunities for developing active forms of engagement and extending the patients’ health maintenance knowledge, which is essential in nursing. One way is to understand more about the concept of coproduction.

Objective:

The purpose was to use experiences from spinal surgery patients’ narratives to explore the conceptual model of healthcare service coproduction.

Method:

A prospective qualitative explorative approach was performed and analyzed in two phases with inductive and deductive content analysis of data retrieved from five focus group interviews of 25 patients with experiences from spinal surgery interventions.

Result:

The findings indicate that mutual trust and respect, as well as guidance given in dialogue, are two important domains. An illustration of how to apply the conceptual model of healthcare service coproduction was revealed in the descriptions of the three core concepts co-planning, co-execution and civil discourse.

Conclusion:

This study highlights what is needed to reach coproduction in healthcare services concerning patients with spinal disorders. Development of care plans that focuses on co-planning and co-execution is recommended which are structured and customizable for each patient situation to make coproduction to occur.

1. INTRODUCTION

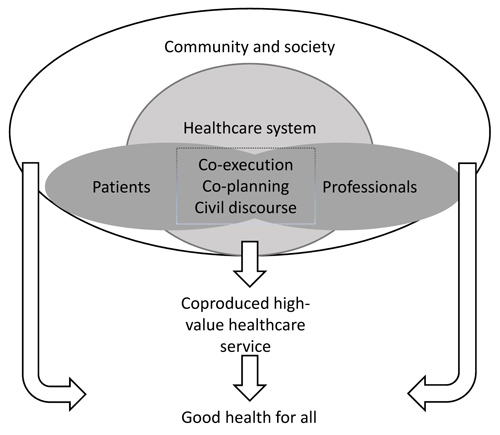

There are a rising number of surgical spine procedures, partially attributed to an increasingly ageing population [1]. Decompression of the spinal canal due to Lumbar Spinal Stenosis (LSS) and removing a Lumbar Disc Herniation (LDH) together constitute approximately 85% of all spinal procedures (approx. 9500 procedures/year) [2] and represent the most common spine procedures in Sweden. First-line treatment is mostly advice, physical therapy and analgesic medications [3], but the rate of surgical treatments has increased over the years [4]. There are several pathways in the healthcare system that a surgical patient takes; from the diagnostic procedure, to operative procedures, hospital admissions, discharge and subsequent recovery [5]. Because there is a high percentage of patients treated with surgery that suffers a risk of not achieving adequate benefits from the procedure and prior to the intervention it is of utmost importance that this is communicated to and understood by the patient. Given that patients’ expectations about surgery may play an important role in the recovery and later perceived quality of care, there is a significant need to understand how this could be shared with patient. The Patient-centered care is one of six fundamental aims stated by the US healthcare system [6] and suggest that informed active patients may be an effective part of facilitating good health outcomes [7]. Good outcomes are more likely if patients seek and receive help in a timely way, where the patient and healthcare professionals communicate effectively to develop a shared understanding about the problem, which can generate mutually acceptable management care plans [8], which is essential parts in nursing. The strong emphasis on engagement and patient participation in general, and shared decision making in specific, has a purpose to give the patient a voice and a choice in each unique situation. This has been widely discussed in the literature. Although, patients still describe themselves as outsiders and left in the periphery and healthcare professionals as insiders and the one with the power to decide. The question is how we could create opportunities to develop active forms of engagement and extending the capacity and the patients’ health maintenance knowledge. The fundamental change lies within the relationship between the patient and the healthcare professional, involving doing with rather than doing for, which could be described by the concept of coproduction. Coproduction argues that patients must be given the opportunity to act as co-participants, co-designers and co-producers [9]. In the conceptual model of healthcare coproduction, patients and professionals interact as participants within the healthcare system (Fig. 1). Within the space of interaction, the model explicitly recognizes different levels of a co-creative relationship. Three core concepts at different levels are defined. At the basic level, good service coproduction requires civil discourse which means a respectful and effective communication between patient and professional. The second level core concept is shared planning or co-planning that invites a deeper understanding of values and expertise. The third level is shared execution or co-execution which demands trust and mutually shared goals on responsibility and accountability of performance [8]. Still, there is a challenge in the translational gap between policy and practice since there is a matter of organizational dispositions of personal attributions and conflicting assumptions about what coproduction is [10]. Therefore, an understanding of coproduction and how to apply and understand this concept in clinical practice is needed. The aim was to use experiences from spinal surgery patients’ narratives to explore the conceptual model of healthcare service coproduction.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Methodological Approach

In phase one, a qualitative inductive analysis [11] from patient’s narratives were performed and in phase two, a deductive approach was used, where the subcategories from the inductive analysis was compared to the core concepts in the conceptual model of coproduction [12].

2.2. Participants

To be enrolled in the study, patients (aged over 18 years) had to fit a set of inclusion criterion: Had undergone one of two spinal surgical interventions; LSS, or LDH in the previous six months; could speak and understand the Swedish language and provided informed consent for participation. To be eligible, at least five weeks must have elapsed since the surgery to assure that any postoperative discomfort was not present before attending the interview. In total, 31 patients were eligible for participating in the study, but six patients failed to come the days for the interviews; therefore 25 participants were included in the study. The age range of participants was between 24-84 (mean age 62; median age 65 respectively) and 14 of the 25 participants were women. Seven of all participants had experienced at least two surgical interventions.

2.3. Data Collection

All participants operated at one of the three hospitals in the southern part of Sweden attended one of five focus-group discussions which were conducted by two experienced qualitative researchers (BH and CP). Two interviews were conducted at a regional hospital (group 1 and 4; n=10), two interviews at a university hospital (group 2 and 5; n=8) and one was conducted at a private hospital (group 3; n=7). A stakeholder at each department contacted the participants and invited them to the interviews which were conducted in a selected room at each department. Focus-group discussions are semi-structured discussions between 4-12 participants that aim to explore a specific issue with the intent to encourage participants to share their common experiences. A moderator (BH) led the interviews by using an interview guide which was based on four open-ended questions (Table 1) intended to facilitate discussions in the group.

An observer (CP) attended the sessions and was given a summary of the group discussions at the end of each interview to give participants the opportunity to clarify their statements. Participants answered the questions individually but were encouraged to talk and interact with each other during the interviews [13]. The number of participants in the focus-group interviews varied between three and seven participants and the focus-group discussions lasted 60-110 minutes. All interviews were audiotaped and then transcribed verbatim.

2.4. Data Analysis

In the first phase, data was analyzed using inductive content analysis, which is a technique to make replicable and valid inferences from written texts [14]. After reading the written text several times, notes were written that illustrated the essential features of the descriptions regarding the process of care experienced by the participants in the context of spinal surgery. Notes were sorted as codes into coding sheets and codes with similarities were separated and grouped into preliminary categories. By going back and forth between the preliminary categories and codes, four sub-categories emerged. Finally, the sub-categories were abstracted into two generic categories, which were based on the underlying meanings describing experiences from spinal surgery interventions [11]. To increase credibility, two authors (CP and SB) with experiences of inductive content analysis performed the analysis in an open and critical dialogue and a third author (BH) confirmed the analysis. Trustworthiness was assured by using authentic quotations from all interviews to elucidate each subcategory [15] and by using an audit trail [16]. In the second phase, a deductive analysis was performed using the conceptual model of healthcare service coproduction, as described by Batalden et al. (2015) [8]. The deductive phase is described as retesting existing data in a different context which involves testing categories in a model or theory. Subcategories from the inductive analysis was analyzed for its correspondence to the conceptual model of healthcare service coproduction [11] and was performed by three authors (CP, BH and PB).

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The principle of autonomy was guided by the informed consent of the participants to process their weigh of the risks and benefits for participating. All participants gave their written consent to participate before entering the interviews and the information about the right to withdraw at any time was given prior to the start of the interviews [17]. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Linköping University, Sweden (Dnr: 2015/10-31).

3. RESULTS

First, the results from phase one are presented with the two generic categories that emerged in the inductive content analysis. Two generic categories were found, described as “Mutual trust and respect are crucial” and “Information being given in dialogue”. Two different subcategories describe each generic category. Secondly, phase two with the linkage to the conceptual model is described.

3.1. Mutual Trust and Respect are Crucial

Trust and respect have their foundation in an individual treatment, being understood as being a person and phrased as “see me”. Each patient has its own unique experience of symptoms such as pain, fear, frustration, and worry. To be listened to by the professional and to be given time to describe their personal situation is considered as a step of being treated with respect: Each symptom and problem due to the medical condition causes different types of interference in everyday life. In the phase of mutual trust and respect, the patient needs to have their problems taken seriously and put into context; if they are a single parent or self-employed, their situation might be affected differently than someone in a dual-parent household or someone in full-time employment.

| Area of interest |

|---|

| Tell me about your meeting with the healthcare service (before, during, and after the surgery). |

| Tell me about the information you had and the need of support during the procedure. |

| Tell me about your everyday life after the surgery. |

| Tell me about your experiences of the key points during this journey. |

| Generic categories | Subcategories | Linkage to core concept |

|---|---|---|

| Mutual trust and respect are crucial (“see me”) | Understanding the unique patient situation | Civil discourse |

| Demonstrating action according to circumstances | Co-execution and civil discourse | |

| Guidance Being given in dialogue (“describe to me”) | Desiring to know what and why | Co-planning and civil discourse |

| Having written information as support | Co-planning and civil discourse |

3.1.1. Understanding the Unique Patient Situation

To be treated as an individual by the healthcare professionals was described in different ways. Professionals were supportive, helpful, and skilled, which provided patients with a feeling of security. The importance of being taken seriously was described, but this was not always met, which sometimes led to extended suffering and worry.” ...but I knew that it was spinal stenosis I thought…but they [at the primary unit] said no we cannot know for sure it could be something else so why don’t you try with some physical therapy” (group 5). Another aspect described was the problem of being absent from work during long periods of time due to the symptoms of pain and fatigue, which was experienced as being frustrating. The feeling of fear about the risks of surgery or if the surgery could be unsuccessful was articulated, which was also expressed by patients’ spouses. A feeling of fear prior to surgery was prominent and this feeling needed to be discussed together with the surgeon to help the patients to feel secure. “it is untenable…. being on sick leave for three months and then back to work for two…. back to sick-leave again (group 4).

3.1.2. Demonstrating Action According to Circumstances

Spinal care is complex because several actors are involved. Communication between providers is pivotal when referrals and investigations such as imaging (X-ray, CT scan, MR) need to be performed before another action can be taken. “It wasn’t until I got another doctor…I had to fight nearly two years without anyone listening to me and sending me to investigations…like an x-ray of my spine” (group 3). Mistakes can cause delays, for example when sent referrals got lost, or results from investigations were missing. This caused frustration and anger according to the patient’s perspective. “My referrals got lost…. there was another year waiting for surgery…. this caused me more pain and discomfort” (group 4). When several departments were involved in the care, an increased risk for mistakes occurred, which the patients understood as a lack of communication between providers. In the phase before getting diagnosed, patients described that they were forced to repeat their wishes to have their problems investigated, for example getting a referral to the orthopedic or neurosurgical department. This was exemplified as a fight for one’s rights.

3.2. Guidance Being Given in Dialogue

The dialogue with the provider about the action taken and process of further care was described as the need for information about “what” and “why”. The requirements about having written information about “how”, as a guidance for further care, could imply a method of support in the patient’s situation and this could be illustrated by the phrase “describe to me”.

3.2.1. Desiring to Know What and Why

Information about treatments elective surgery in this case was described in detail. The ability to make own choices was understood as an opportunity to be involved. Being involved assumed confidence and trust for the doctor, which implies the need to meet the same doctor several times. In the discussion with the doctor, the patients asked to know more about risks and benefits before making the decision to go through a spinal surgery intervention. This was also an attempt by the patients to prepare themselves for the consequences after the surgery. “I asked a lot before…. what I was going to be able to do or not after surgery…because I wanted to be prepared so I knew what to expect and have time to plan” (group 1). A wish to know to what extent they could be physically better, especially if they had gone through surgery before was also revealed. It was a prominent detail in the patients’ responses to know what was going to occur, since not knowing could cause them worries. With proper information, it was possible for the patient and their family to plan their everyday life; taking sick leave and relaying this information to their employer. “For me, it’s important to know before something is happening…then you have a chance to be prepared and think of what is likely to happen…” (group 5).

3.2.2. Having Written Information as Support

Oral information could be complemented with written information concerning the routines about the procedure and how to handle the scheduled exercise after surgery which was appreciated by the patients: “A paper with everything described is good…. then you can read everything again by yourself after the visit at the clinic” (group 3). This information was helpful for patients to better understand the procedure and to prepare them for what was going to happen. Another aspect was the opportunity to read the information again when coming home, or to share this written information to spouses that did not attend the encounters with the doctor: “The physical therapist showed me how to do my exercise and then I got a paper with instructions…so I knew how to do everything” (group 2).

3.3. Linkage to the Conceptual Model of Healthcare Service Coproduction

In the second phase, the linkage to the conceptual model of coproduction was performed. The subcategories that emerged in the inductive content analysis was compared to the three core concepts described in the model. Results of the linkage are presented in Table 2.

Civil discourse was linked to all four subcategories and it was explicitly described in the narratives as being met as a unique person. This was understood as a need for concerns and considerations taken for the patients’ situation and that the professionals acted as attendants. When referrals got lost, this warranted a need for support and understanding due to the precarious situation. Furthermore, a civil discourse is a desideratum demonstrating the need and desire to know what and why things were happening. The guidance from professionals to support patients in their recovery (after surgery) also requires a civil discourse by means of adapting the information to each specific situation. The core concept of co-execution was linked to demonstrating action according to circumstances that were illustrated by patients who wanted the professionals to act in the given situation. This was a central aspect, with descriptions made by patients that they were forced to wait because of the lack of communication between different providers. Co-planning is linked to the desire to know and have written information as support, which was illustrated by patients requiring information about the next step of the diagnostic procedure or treatment after surgery. Patients also requested information regarding the cause of their condition.

4. DISCUSSION

This study explored patients’ experiences from the care process of spinal surgery, describing that mutual trust and respect as well as guidance given in dialogue are two important domains. As an illustration of how to apply the conceptual model of healthcare service coproduction, the linkage revealed descriptions of the three core concepts in the model, which could be helpful in deciding when to apply coproduction in a spinal surgery setting. The results could reinforce the conceptualization of what coproduction means and add more knowledge about the descriptions of the three core concepts.

Mutual trust and respect are crucial, interpreted as “see me”, which is one fundamental aspect in understanding civil discourse. It has been found that professional interactions are associated with increased wellbeing over time in patients living with chronic illness. Therefore, the investment in the relationships and communication between professionals and patients is of importance [18], which is in line with the core concept of civil discourse. Active communication assumes participation and production of services, active participation is needed by those that are receiving the service [19]. Healthcare services must always involve the needs of an individual or a population. This could potentially contribute to a shared aim concerning both the patient and the professional [20]. The process of coproduction must consider patients and professionals understanding of participation and engagement; forms of communication, power of dynamics that may be reconfigured throughout the coproduction of healthcare services [10]. Coproduction could also be a challenge of conventional framings of engagement and involvement as well as commonly held notions about authority and capability [10]. This is one aspect in creating work settings that could contribute to a sense of mastery in the healthcare service, when leadership in organizational management understands and facilitates the coproduction of healthcare delivery as well as knowledge development [20].

Guidance given in dialogue interpreted as “describe to me” is important in the process of co-planning and patients expressed their desire to receive an oral explanation as well as having written information. In healthcare, there are two parties (patient and provider) who need to work together in a relationship, which is central when it comes to the concept of “service”. In this relationship, an agreement on which activities is to be made should be completed to reassure coproduction. This relationship is held together by skills, knowledge, habit, and the open pursuit of truth and must carry some willingness to be vulnerable to one another. Historically, the focus has been on taking actions, visible and bounded in context and in time, whereas relationships have been assumed [20].

If people are actively involved in coproduction in their healthcare, they need good quality information about relevant options, pros and cons, and about expected outcomes. Timely information during care is still an expectation rather than a norm and therefore strategies are needed to complement and support the provision of information made by both professionals and patients if coproduction would become a reality. The lack of understandable evidence-based information and the patient role as an active contributor in their care is still emerging and sometimes growing [20]. For this role to be active, effective ways to communicate with patients and provide them with information that could facilitate their active role during treatment and recovery is needed. The need for appropriate and timely information indicates that patients’ concerns go beyond the fundamental basics of delivering appropriate care, which also has been described by others [5, 21]. Cleary, there is a need for professionals to provide information that is comprehensive and sensitive to a patient’s needs and values. Procedures could be trivial to professionals, who are used to working in a surgical environment, but this should be explained for patients who might be in a new and frightening situation. As the patients in this study described, both oral and written information was important, which has been found by others [22], yet this seems to be difficult to accomplish in practice. To be responsive to each individual unique wish about participation and need of information is fundamental if coproduction of healthcare delivery is to become a reality.

Demonstrating action according to patients’ circumstances was linked to the process of co-execution. This highlights a need to provide tailored care to each individual person per their preferences and needs, rather than adopting a “one size fits all” approach. In line with our results and the conceptual model, a review by Hopayian and Notley (2014) found strong connections between relationships and interpersonal skills and what they describe as personalized care. This is based on patients’ preferences and needs in receiving the correct information about their condition, management and self-care [23], which is connected to co-execution, which demands trust and shared goals. To accomplish this, several elements are needed to facilitate the activation of patients. First, patients must be ready; mentally and emotionally ready to engage. Then, a curiosity amongst professionals to ask questions according to patients’ circumstances and identify sources of trustworthy information is needed, but also, to participate and be present and committed in the relationship with the patient [24]. However, to simply give information is not enough and patients need to be furnished with the skills and confidence to implement the advice that has been given to them [25].

4.1. Methodological Considerations

This study has limitations due to the results relying on two conditions related to spine conditions, thereby possibly limiting the study transferability. However, the data provides rich and novel information from the participants and it is probable that patients with other conditions comparable to spinal disorders may have similar experiences. The location of the focus groups may have affected the results, given that participants have been less willing to describe negative experiences. The sample of convenience may have affected the results since those participants were more willing to provide their experiences and therefore more likely to have been participating. The results of this study rely on participants’ recollections of their surgical intervention and it should be considered that memories could be selective and not represent a truly accurate picture of their experience.

When using qualitative methodology, trustworthiness can be seen in light of credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability [26]. In our study, credibility was assured by debriefing sessions between the authors during the analytical process. Dependability refers to the stability of data over time and was established by performing interviews at different clinics during the study period until saturation was achieved. Conformability means that the data accurately represents the information provided by the participants and was not invented by the inquirer; therefore, authentic quotations were used. Transferability is assured by descriptions of participants and settings, but given the study design, a generalization of findings is limited. Thus, study results can guide healthcare professionals in gaining an understanding about coproduction in general and how to apply coproduction in a spinal surgery setting.

CONCLUSION

This study highlights what is needed to reach coproduction in healthcare services concerning patients with spinal disorders. Civil discourse is the essential concept, meaning the building of a strong relationship and good communication between the patient and professional to aid the understanding of patients’ unique situation. Co-planning is understood as guidance to patients by describing what and why things are happening in each situation. Co-execution is the phase in which patients are provided with proper support in understanding how to act and why, and to enable the patient to be properly prepared during the spinal surgery intervention process. The implications for nursing that we would like to propose are the development of care plans that focus on co-planning and co-execution, which are structured and customizable for each patient situation to make coproduction happen. Furthermore, when professionals give information to patients, an automatic follow-up consultation should be a requirement to assure that patients have understood and are knowledgeable about how to act if a specific situation occur, for example, complications following the surgery. The implementation of communication skills training for professionals in practical training during education and continuously during practice, for example by video-recording encounters, will help to promote civil discourse. Future research could focus on developing outcome measures for the three core aspects in coproduction to enhance the exploration and implementation of coproduction in healthcare settings.

FUNDING

The study was supported by grants from Futurum Academy for Health and Care, Region Jönköping County, Jönköping, Sweden.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Linköping University, Sweden (Dnr: 2015/10-31).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals were used in this research. All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Inform consent has been obtained from all participants.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.