RESEARCH ARTICLE

Post-discharge Follow-up Care: Nurses' Experience of Fostering Continuity of Care: A Qualitative Study

Hanny Handiyani1, *, Moh Heri Kurniawan2, Rr Tutik Sri Hariyati1, Tuti Nuraini1

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2024Volume: 18

E-location ID: e18744346284419

Publisher ID: e18744346284419

DOI: 10.2174/0118744346284419240205145438

Article History:

Received Date: 05/12/2023Revision Received Date: 06/01/2024

Acceptance Date: 16/01/2024

Electronic publication date: 13/02/2024

Collection year: 2024

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background

In contemporary healthcare, ensuring continuity of care beyond hospitalization is imperative for optimizing patient outcomes. Post-discharge Follow-up Care (PFC) has emerged as a crucial component in this endeavor, especially with the integration of virtual platforms.

Objective

This study aims to thoroughly investigate nurses' experiences in providing Post-discharge Follow-up Care (PFC) to improve its implementation.

Methods

A descriptive qualitative study was conducted to explore nurses’ experiences of conducting nurse-led follow-up care. This study was conducted at University Hospital, involving nine nurses with experience in administering PFC. Data were collected through focus group interviews. Thematic analysis was performed to identify recurring patterns and themes within the data.

Results

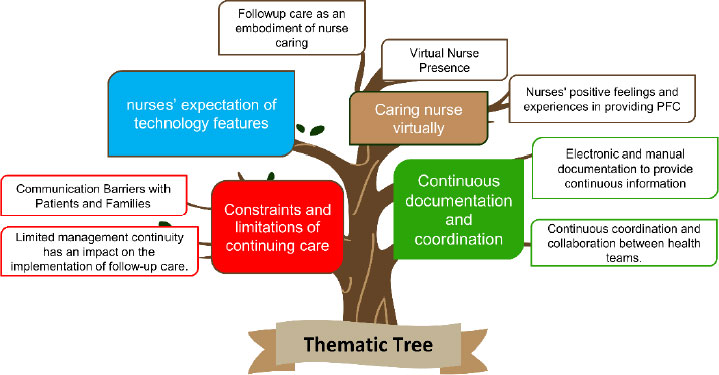

The thematic analysis yielded four overarching themes: 1) “Caring nurse virtually,” emphasizing nurses' dedication to compassionate virtual care, 2) “Constraints and limitations of continuing care,” highlighting challenges in resource management and coordination, 3) “Continuous documentation and coordination,” underscoring their vital role in seamless patient care, and 4) “Nurses’ expectation of technology features,” showing nurses' hopes for advanced features to enhance PFC.

Conclusion

This study provides deep insights into the experiences of nurses in delivering PFC through virtual platforms. It underscores the significance of maintaining emotional connections with patients, even in a virtual environment. The challenges faced in resource management and coordination highlight areas for potential improvement. Additionally, the study highlights the crucial role of accurate documentation and inter-team coordination in ensuring the continuity and quality of care. The nurses' expectations for technological advancements emphasize the need for ongoing innovation in healthcare delivery. These findings collectively contribute to the ongoing evolution of virtual follow-up care practices, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes and experiences beyond the hospital setting.

1. INTRODUCTION

The shift towards discharging patients with chronic conditions from hospitals has led to the need for increasingly complex post-discharge care. After hospital discharge, patients may transition to various healthcare settings within the national health system [1]. These settings can include primary care clinics, rehabilitation facilities, home healthcare services, and specialized outpatient clinics. In some healthcare systems, there may be intermediate care facilities or step-down units that offer a bridge between hospital care and home-based or community-based care. This transition period can be fraught with anxiety and stress for both patients and their caregivers, and studies indicate that a significant portion of patients struggle to comprehend their post-discharge care plans [2]. A potentially beneficial intervention to facilitate this transition and enhance patient outcomes is the implementation of post-discharge follow-up care (PFC).

PFC is viewed as a positive practice carried out by various hospital-based personnel to exchange information, offer aftercare guidance, manage symptoms, promptly identify complications, and provide reassurance during the shift from hospital to home [3]. Additionally, PFC is recommended as a cost-effective strategy to enhance patient health, boost satisfaction, and diminish unplanned readmissions [4, 5]. Various objectives and endpoints for conducting PFCs have been cited, including the improvement of care quality and continuity, heightening patient safety, reducing adverse events, ensuring patient comprehension of discharge instructions, gathering patient feedback on their care experience, and addressing any concerns about their recovery or experience [6-8].

Nurses have identified post-discharge follow-up care as a valuable means of caring for patients and fostering stronger nurse-patient relationships [9, 10]. However, this type of care can be challenging for nurses due to the potential for intense emotional involvement with patients and their families [9].

This study delves into the experiences of nurses of a University Hospital in Indonesia concerning care substitution, focusing on its benefits, barriers, and prerequisites. This study aims to thoroughly investigate nurses' experiences in providing PFC to improve its implementation. It is important to note that care substitution may not encompass all aspects of follow-up but may specifically pertain to certain procedures.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Design

A descriptive qualitative approach was employed to analyze and provide an overview of various data collected through interviews, observations, and examination of issues occurring at the research site [11, 12]. The researcher directly explored, analyzed, and described the phenomena under investigation through the revelation of the researcher's insights. The investigation delved into the firsthand exploration of experiences and feelings related to the provision of nurse-led follow-up care in inpatient settings. Data were collected from April to September, 2023.

2.2. Setting and Participants

A purposeful sample of primary nurses from a University Hospital was invited to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria for participants in this study were: 1) experience as a nurse in the hospital for at least 1 year, 2) nurses who follow-up patients with chronic diseases, 3) educated with at least a Bachelor of Nursing, and 4) willing to be a participant in the study as evidenced by the signature on the research informed consent letter. A total of 9 nurses who met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in this study.

2.3. Data Collection

The study employed focus-group discussions as a research methodology. This approach proves highly advantageous for delving into a collective cognitive reservoir and perspectives regarding a particular subject matter. Leveraging group dynamics, focus-group interviews have the capacity to yield substantial and multifaceted data and foster extensive discourse. The interview guideline consisted of eight open-ended questions to explore nurses' experiences in conducting nurse-led follow-up care, including 1) How is PFC implemented? 2) How to ensure that relevant and important patient information is well-documented and available to the next responsible nurse? 3) What kind of parameters are usually collected? 4) How do you feel when undergoing PFC activities? 5) How are PFC activities monitored? 6) What is the process of interaction with patients during PFC? 7) How to improve the technological competence of nurses in continuing care services? 8) What features are needed to support continuing care for patients with chronic diseases?

Probing inquiries were implemented to stimulate participants in furnishing additional information. Bracketing was applied throughout the interview phase, a crucial step in mitigating potential biases that might impinge on the research aim. The interview session, which took place at the hospital, spanned a duration of 60 minutes.

The study incorporated the utilization of a digital video recorder alongside the documentation of non-verbal cues observed during the interviews. Prior to data collection, participants were provided with a comprehensive overview of key research components, including the utilization of a digital recording device, the study's objectives and potential benefits, as well as the anticipated duration of the interviews. Additionally, informed consent was secured electronically through Google Forms prior to the commencement of the interviews. Notably, the primary author, a doctoral student and practicing nurse affiliated with a distinct hospital, candidly acknowledged their previous experiences and preconceptions at the onset of the investigation. This proactive step was taken to enhance the credibility of the findings, fostering an environment of receptivity and mindfulness towards the nursing perspective. The primary author spearheaded the analytical process, engaging in ongoing dialogues with co-authors to ensure rigor and comprehensiveness in the interpretation of the data.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

Participants were duly informed of the study's objectives and interview procedures through a formal invitation letter. It was underscored that participants retained the prerogative to withdraw from the study at any point prior to the dissemination of results. Subsequently, all participants provided written consent to engage in the study. During the focus-group interviews, the information conveyed in the invitation letter was reiterated, with a specific emphasis on the importance of upholding confidentiality within the group. The Helsinki Declaration has been followed for involving human subjects in the study. The study received ethical clearance, allowing for the storage of personal data and endorsing the research initiative, from the hospital ethics committee at Rumah Sakit Universitas Indonesia (Ethical Approval Number: S-014/KETLIT/RSUI/III/2023). Approval to conduct the study was granted by the hospital administration.

2.5. Data Analysis

The primary objective of this study was to elucidate the underlying patterns of significance derived from the accounts of participants' experiences pertaining to post-discharge follow-up care. To optimize the efficacy and efficiency of the research endeavor, the participant pool was adjusted to reach a point of data saturation, which was determined to be approximately nine Primary Nurses (PNs) at the time of the interviews. For the attainment of data saturation, a methodological consensus was agreed upon by the two researchers [13]. The data underwent a rigorous thematic analysis process, entailing the meticulous transcription of interviews followed by repeated close readings. This iterative process enabled the identification of meaning and the subsequent delineation of overarching themes [14]. The final themes were constructed based on detailed process descriptions and were presented in the form of a thematic tree, providing a comprehensive visualization that encapsulated all conceivable nuances, including final themes and subthemes [13].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants’ Characteristics

The participants' characteristics are represented in Table 1. All nurses who became participants were female and had a Bachelor of nursing education with the most previous experience of >2-3 years. Most participants worked in the inpatient ward. Each nurse provided post-discharge follow-up care in one month, averaging in the range of 1-20 patients/month.

3.2. Thematic Findings

The thematic tree was employed as a visual representation to elucidate the outcomes of this investigation, offering multifaceted insights into nurses' encounters while conducting PFC (Fig. 1). The thematic analysis yielded four overarching themes: Caring nurses virtually, constraints and limitations of continuing care, continuous documentation and coordination, and nurses’ expectations of technology features.

| Demographic Characteristics | n |

|---|---|

| Age | 25 – 29 Year |

| Sex | |

| Female | 9 |

| Previous experiences | |

| 1-2 years | 1 |

| >2-3 years | 5 |

| >3-5 years | 3 |

| Education | |

| Bachelor of Nursing | 9 |

| Working unit | |

| Inpatient Room | 5 |

| Intensive Room | 4 |

| Average post-discharge follow-up | |

| 1-20 patients/month | 6 |

| ≥ 20 patients/month | 3 |

3.2.1. Theme 1: Caring Nurses Virtually

This theme explains how nurses perceive that in providing follow-up care services remotely with the help of technology, nurses still provide full care. This theme consists of three detailed subthemes as follows:

3.2.1.1. Subtheme 1.1: Follow-up Care as an Embodiment of Nurse Caring

PFC activities carried out by nurses are a way to be able to provide care to patients and form more communication intensity with patients and families after treatment in the hospital. As expressed by a nurse:

“Follow-up care, in itself, is a way for us to demonstrate our continued concern for the patient because their treatment is not confined to just their time in the hospital; it shows that we still care even after they have been discharged.” She further added: “Through follow-up care, we can have more extensive communication with the family regarding any challenges they face and their experiences in caring for the patient ” [P7].

|

Fig. (1). Thematic tree. |

3.2.1.2. Subtheme 1.2: Virtual Nurse Presence

The virtual presence of nurses is an effort of nurses to always provide care to patients, especially in the use of platforms that facilitate patients, such as WhatsApp and telephone, as well as access to communication that is easily accessible to patients. For example, participants stated:

“Patients' families are more comfortable using WhatsApp” [P6].

“Sometimes, the patient is not due for follow-up care yet, like within three days, but the family, you see, already knows our WhatsApp number, so they sometimes inquire through WhatsApp” [P7].

“...even calling late into the night, continuously” [P8].

3.2.1.3. Subtheme 1.3: Nurses' Positive Feelings and Experiences in Providing PFC

The nurses reported that providing follow-up care gave the nurses positive feelings and experiences, as well as a sense of pride in their PFC in building closer relationships with patients. Nurses expressed the following statements:

“Expressions of gratitude mean a lot to us because it shows that our efforts, despite the exhaustion, are beneficial to people like them” [P9].

“Suddenly, their family contacts us again just to express their thanks, even though the patient passed away a long time ago. After several months, they still reach out to us and even want to give us a small token of appreciation. This truly means they still remember us” [P2].

“There was a patient who said, 'Other hospitals do not do this,' but this Hospital does. It is quite an appreciation, and it makes us proud because it finally dawns on us that being a nurse is not just about providing service in the hospital, but even after discharge, we can still provide that kind of continuous care” [P1].

3.2.2. Theme 2: Constraints and Limitations of Continuing Care

Various obstacles were faced by nurses in providing PFC related to communication problems with patients and families and limited management continuity. This theme consists of two detailed subthemes:

3.2.2.1. Subtheme 2.1: Communication Barriers with Patients and Families

In some cases, there were communication barriers between nurses, patients and families. For example, one participant mentioned:

“Usually, when the number displayed on the phone starts with '021,' it is often seen as a random or unknown number to us. So, they might not want to answer” [P2].

The impact felt by using the hospital telephone number is the disconnection of communication with patients, as conveyed by a participant as follows:

“For instance, we attempted to follow up three times, but they did not answer. So, we would not continue with the follow-up care” [P4].

3.2.2.2. Subtheme 2.2: Limited Management Continuity has an Impact on the Implementation of Follow-up Care

The limitations faced were mainly in the PFC implementation schedule, which was carried out before or after the nurses' work schedule. Another limitation was the limited facilities in the room to conduct PFC. Some nurses reported:

“The follow-up care can be conducted during the morning shift or the afternoon shift before the afternoon shift starts. This is because sometimes, on a given day, there might be a lot of patients discharged, not just two or three. It could be, for example, five, and they are divided among the morning shift until around 5 PM, and then continue in the afternoon shift” [P4].

“However, if we use our personal WhatsApp, it is limited because the tablet is also used for other purposes, so we cannot respond immediately” [P7].

The condition, where nurses perform PFC with the amount that nurses feel is overloaded, has an impact on helping their superiors (Clinical Care Manager) and the experience of fatigue felt by nurses. The following are some nurses' statements:

“If, for example, the ward is crowded with patients, we are already overloaded. Normally, one nurse is assigned to six patients, but sometimes it could be more than six. So, then the Clinical Care Manager steps in to assist” [P3].

“The number of patients we follow up with exceeds six in a day, especially if there are many others. It feels more exhausting” [P3] [P4].

This sentiment was echoed and affirmed by all participants in the focus group, as they nodded and smiled in agreement with statements from participants three and four.

3.2.3. Theme 3: Continuous Documentation and Coordination

Continuous documentation and coordination were a finding in the implementation of PFC at the hospital where nurses documented electronically as well as manually to ensure ongoing data and coordination experiences experienced by nurses during PFC. This theme consisted of two detailed subthemes:

3.2.3.1. Subtheme 3.1: Electronic and Manual Documentation to Provide Continuous Information

Some nurses said that documentation was done electronically and manually during the implementation of PFC. The following is the nurse's statement:

“…We document it in a spreadsheet...” [P2] [P7].

In addition to electronic documentation, one of the nurses also conveyed the manual documentation process.

“We have a manual book, so there is a backup” [P2].

The data and parameters documented during the PFC were revealed by the nurse as follows:

“The patient's name, medical record number, prescribed medications, follow-up date, discharge documents, and then the family member's contact information for education. Also, details about the prescribed medications upon discharge, their follow-up schedule, and the phone number for follow-up” [P2] [P7].

Furthermore, another nurse expressed the importance of continuous information:

“…The patient's identity, medical diagnosis, responsible doctor, responsible nurse, nursing diagnosis, date of discharge, follow-up date, followed by the follow-up care plan, who conducted the follow-up care, and the outcomes of the implemented follow-up care” [P1] [P7] [P4].

3.2.3.2. Subtheme 3.2: Continuous Coordination and Collaboration between Health Teams

The process of coordination and collaboration is carried out in the implementation of PFC. Coordination is carried out when the patient gets discharge planning before going home, such as the following nurse's statement:

“Usually, when we educate a patient before discharge, there are three people involved: a nurse, a pharmacist, and a nutritionist... Typically, we provide their family's phone number to the nutrition and pharmacy departments...” [P2].

Furthermore, the organizing of PFC has been arranged and implemented in each inpatient room.

“We organize it based on MPKP, so for example, if there is a patient, Mr. A, who is their NPJA, let's say... So, if, for example, it has been 3 days since they were discharged, on the third day, their AN or PN will conduct the follow-up care. So, the team responsible for the follow-up care will be either the PN or AN on duty on the third day after the patient's discharge. That means it will be a nurse” [P8].

3.2.4. Theme 4: Nurses’ Expectations of Technology Features

The nurses expressed their expectations regarding the development of technological features that could improve the quality of information obtained in the PFC. These features are integrated systems, video call features, and scheduling features. The following are quotes from nurses regarding this matter:

“Hopefully, there could be video calls...” [P2] [P7].

“Something like an app that we can access..., a specific menu that allows us to directly connect with their families...“ [P6].

“…difficulty in scheduling follow-up care” [P9].

4. DISCUSSION

The research findings on the theme of nurse caring activities provided virtually demonstrate the enduring aspect of nursing care provided by nurses in a virtual environment. Virtual nursing care is an emerging area of nursing that has the potential to expand the reach of nursing care beyond the confines of the hospital [15]. Remote communication can serve as a tool to expand the nurse's engagement with patients beyond the confines of the hospital [16]. This is in accordance with the notion of human caring, which arises from nurses' endeavor to dynamically attend to their clients through an amalgamation of scientific knowledge, artistic expression, and spiritual sensitivity [17]. Human caring holds a certain level of subjectivity and calls for transpersonal and ethical interactions between a nurse and an individual, acknowledging them as two distinct beings with unique circumstances [18]. The advantages of such care are immeasurable, fostering self-realization on both personal and professional fronts [19, 20]. Therefore, virtual nursing care serves as a platform for nurturing exceptional human qualities and enduring connections between patients and nurses [21].

Accessibility and comfort in remote interactions are crucial aspects of virtual communication. The context of this study reflects how the nurse's virtual presence through platforms like WhatsApp and telephone creates a comfortable space for patients and their families to communicate. This underscores the integration of technology as a tool to facilitate nursing care [22]. Nurses reported that providing follow-up care brings about a positive experience and a sense of pride. The study results identified that, during the implementation of Post-Discharge Follow-Up Care (PFC), nurses actively made individual contributions, which could not only present emotional challenges but also foster an increased understanding and drive towards their own professional growth [23]. These findings consistently support the view that providing follow-up care yields a positive experience for nurses, ultimately contributing to the overall enhancement of healthcare quality.

The second theme in this study reflects the constraints faced by nurses in providing Post-Discharge Follow-Up Care (PFC), which can be associated with the concept of continuity management in healthcare services. Previous research highlighted the challenges in delivering continuous care, particularly in terms of communication and coordination [24]. The identification and resolution of obstacles are pivotal in achieving efficiency and quality in healthcare services. The communication constraints identified in this study mirror the challenges encountered in establishing effective relationships through remote interactions. Communication and interpersonal skills in the context of healthcare underscore the importance of effective communication for the success of interactions among nurses, patients, and families [25].

The constraints in scheduling PFC and the limited facilities reflect the challenges in resource management for providing continuous care. The findings in this study consistently demonstrate that communication barriers with patients and families, as well as limitations in continuity management, are tangible hurdles faced by nurses in PFC. This aligns with the findings of a study [26], which emphasized that obstacles at the institutional level, such as scheduling care system issues, were consistently the most frequently encountered. Furthermore, another study emphasized the significance of addressing challenges in continuous care, including insufficient coordination, inadequate hospital preparedness, and underutilization of available resources and capacities. Together, these insights underscore the need for comprehensive strategies to enhance the quality and effectiveness of healthcare delivery [27].

The research results highlight the importance of coordination between nurses and other healthcare team members in executing follow-up care. Effective coordination ensures that patients receive continuous and well-coordinated care after being discharged from the hospital [3]. This is particularly evident in the discharge planning process, where nurses, pharmacists, and nutritionists collaborate to ensure that patients have an appropriate care plan. Additionally, the research findings emphasize the crucial role of documentation in the implementation of follow-up care. Nurses utilize both electronic and manual documentation methods to ensure that the necessary information for providing continuous care is available and easily accessible. A study discovered a robust correlation between the absence of a designated healthcare provider or facility for follow-up care in the hospital discharge summary and adverse outcomes for patients transitioning to the hospital [28].

The findings in this study reflect the nurses' expectations regarding the development of technological features, including video calls and integrated systems. This perspective resonates with the notion that technological innovations possess the potential to not only bolster efficiency but also elevate the overall quality of healthcare provision. For instance, video technology can enable nurses to provide care remotely, improve access to care, reduce healthcare costs, and increase access to specialist expertise [29], while data integration enables nurses to access patient information quickly and efficiently, reducing human error and streamlining patient care [22, 30]. However, it is essential to consider the potential benefits, limitations, and professional implications that affect the adoption and use of these technologies.

CONCLUSION

This study provides profound insights into the experiences of nurses in delivering PFC in a virtual context. The first theme indicates that nurses are able to maintain a sense of care towards patients through technology, underscoring the importance of sustaining emotional connections with patients even in a virtual environment. The second theme highlights the challenges faced, particularly in resource management and coordination, when providing continuous care. The third theme underscores the significance of accurate documentation and inter-team coordination to ensure patients receive seamless and coordinated care. Additionally, it sheds light on the nurses' expectations for enhancements in technological features and reliability in administering PFC. To enhance the generalizability of the study, future research could involve a larger and more diverse sample of healthcare professionals, including both male and female nurses, and expand the study to multiple hospitals or healthcare settings. This would provide a broader perspective on the experiences and perceptions related to follow-up care, increasing the external validity and allowing for a more widespread application of the study's insights.

LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

The limitations of this study warrant acknowledgment. Firstly, the research was confined to a specific hospital setting and a particular group of nurses, potentially restricting the generalizability of the findings to a broader population. Additionally, while the study provides valuable insights into the experiences of nurses in administering Post-discharge Follow-up Care (PFC), it did not explore the perspectives of patients and their families regarding this service.

ABBREVIATION

| PFC | = Post-Discharge Follow-Up Care |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This research has obtained ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee of RS Universitas Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia, under the reference number S-014/KETLIT/RSUI/III/2023.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this research. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

COREQ guidelines were followed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article is available in the Zenodo Repository at https://zenodo.org/ records/10638630 , reference number 10.5281/zenodo. 10638630.

FUNDING

The study was funded by Directorate of Research and Development at Universitas Indonesia, Funder ID: Hibah PUTI Pascasarjana 2023 NKB-066/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/ 2023, Awards/Grant number: NKB-066/UN2.RST/HKP.05. 00/2023.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are thankful for the contributions of the nurses as participants in this study.